Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Many readily identifiable products carry the name of Switzerland: Swiss cheese, the Swiss Miss hot cocoa mix and (of course) Swiss Army knives. But the Swiss people and their genealogy are a bit more difficult to define. Switzerland is a centuries-old confederation of people with different cultures and who speak different languages—including one spoken only there!—and draw from contrasting ethnicities.

Just as there is no Swiss “ethnicity,” per se, Switzerland has equally been defined by what it didn’t want to be. The country has a proud independent streak, staving off powerful neighbors such as the Hapsburgs of Austria to the east and the French to the west. The result? An economically wealthy nation whose neutrality has been respected for more than two centuries.

While only about a million people in the United States claim Swiss ancestry, that number is somewhat lowballed by the fact that a fair number of Swiss families were “two-steppers” who left Switzerland to seek economic opportunity or religious freedom in states such as the Holy Roman Empire, then journeyed to America several generations afterward. Descendants of this Alpine nation might identify more with the heritage of the second country, rather than their ancestral Swiss ancestry.

ADVERTISEMENT

But those with Swiss ancestry have a mountain of genealogical information available to them. Let’s take a look at Switzerland: its history, records and heritage.

- An Outline of Swiss History

- First Steps for Finding Swiss Ancestors

- Top Swiss Genealogy Records

- Key Online Resources

- Related Reads

An Outline of Swiss History

The Swiss plateau enters recorded history when a Gaulish Celtic tribe called the Helvetii attempted to expand into what’s now western France. Though the Helvetti were driven back by Julius Caesar in 58 B.C., their tribe’s name still resonates today as the official Latin name of the Swiss state: Confoederatio Helvetica, or “Confederation of the Helvetians.” A few decades later, the Swiss lands became part of the Roman Empire, and more Germanic tribes (the Burgundians and the Alemanni) later entered the region.

When the Roman Empire fractured, Switzerland was divided among

several noble houses who served as fiefs of the so-called “Holy Roman

Empire.” To help the empire monitor crucial mountain passes, some regions received “Imperial immediacy” (Reichsfreiheit), meaning their rulers were considered direct subordinates of the emperor rather reporting through several feudal levels.

ADVERTISEMENT

That might have kept the peace, but one noble family (the Habsburgs) upset the balance of power when it annexed the eastern Swiss plateau after a rival family died out in 1264. (The Habsburgs continued to grow in power, eventually coming to rule the Holy Roman Empire.)

In 1291, three regions—Uri, Schwyz and Unterwalden, later known as Waldstätten or “forest cantons”—formed the Old Swiss Confederacy. Within a century, the Swiss Confederation expanded to include another five cantons and city-states, forming the eight “Old Cantons.” By 1500, the Confederation was essentially independent from the Holy Roman Empire and the dreaded Habsburgs. Its territory expanded to include the mostly French-speaking canton of Fribourg as well as the Italian-speaking Ticino.

Expansion continued into the first half of the 1500s, when the Protestant Reformation rocked the Swiss Confederation. Some cantons remained Roman Catholic, while others embraced the “Reformed” Protestant faith preached by John Calvin (in Geneva) and Ulrich Zwingli (in Zürich).

Likewise, the Anabaptist movement spawned the Mennonites, Amish and other sectarians, who had substantial influence in some parts of Switzerland despite being persecuted and often martyred. Anabaptists—who practiced pacifism and believed in a “believer’s baptism” rather than baptizing infants—made up a significant number of the “two-stepper” immigrants, as well as groups who went directly to America.

The Swiss Confederation officially gained independence at the end of the Thirty Years War in 1648. This led to demographic changes: Though the war spared the overpopulated, mountainous Swiss cantons, it ravaged the German states to the Confederation’s north. Rulers of the war-torn German states (such as the Palatinate) granted incentives for Swiss to emigrate there to help rebuild the region’s population.

Economic and sectarian strife occasionally sparked peasant results. One of these rebellions, the Swiss Revolution of 1798, opened the door for the French Emperor Napoleon I to invade. Napoleon abolished the cantons and created the Helvetic Republic, but his Republic did establish the basis for citizenship rules (useful for genealogical research).

After Napoleon’s defeat, the Congress of Vienna restored the canton structure to Switzerland and reaffirmed its neutrality, which has not been violated since. In 1848, the year of revolutions through Europe, the Swiss enacted a more democratic constitution that was modeled on the principles of the US Constitution and the French Revolution.

Switzerland maintained its neutrality throughout later 19th-century conflicts, as well as both World Wars I and II. Today, Switzerland is a wealthy, prosperous nation famous for its scenic views of the Alps.

First Steps for Finding Swiss Ancestors

Meaningful genealogy research in many parts of Europe requires an exact village of origin. This axiom applies to Switzerland, too, but with a few caveats—some positive, and some negative.

For example, genealogists can take advantage of Swiss citizenship records and civil registrations. However, these records are kept at the individual commune/municipality level, rather than at the national or canton (state) level. As a result, a large percentage of Swiss—who may have moved communes during their lifetimes—do not hold citizenship where they live today.

And because civil registrations were kept in the commune that held a person’s citizenship, historical records may not be kept in the same commune where your Swiss ancestor lived in the 1800s or 1900s. You’ll need to do additional research to determine where to find these records.

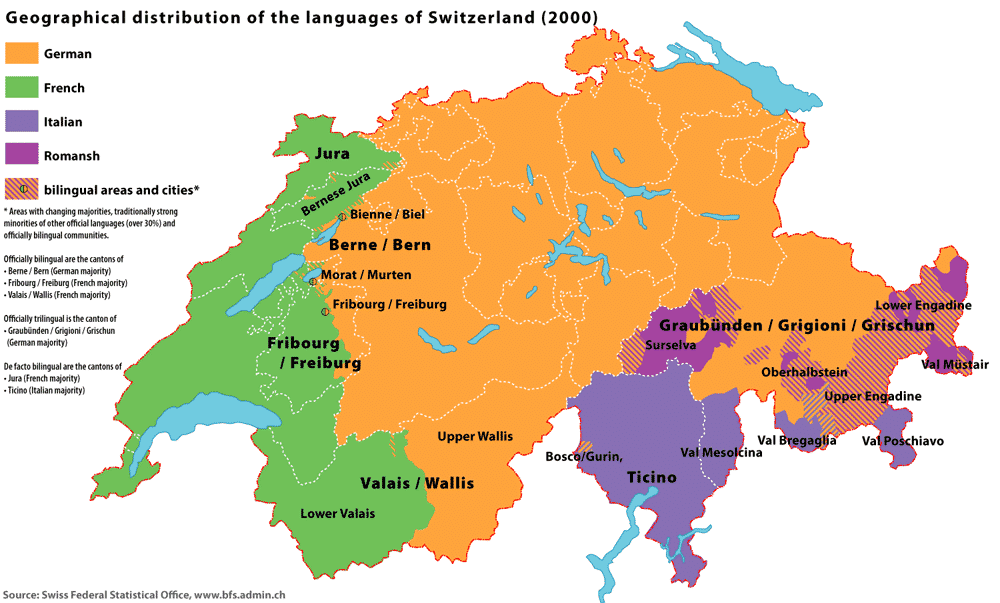

There are 26 Swiss cantons today, and studying them can help you determine your ancestor’s hometown in a variety of ways. Residents of most cantons speak the Swiss German dialect (Schweizerdeutsch), but six of them (Geneva, Vaud, Fribourg, Valais, Neuchâtel and Jura) are predominantly French-speaking, while a seventh (Ticino) is primarily Italian-speaking.

Despite the linguistic differences, many Swiss speak a combination of these three languages. A sizeable minority (mostly in the Graubünden canton) speaks Romansh, a fourth national language that is a descendant of Latin.

Knowing which languages were historically common in each canton will help you find and interpret records of your Swiss ancestors. US records that mention Swiss immigrants might indicate a hometown directly (like in passenger lists), or provide a clue by mentioning the individual’s mother tongue (like in US census records).

For example, if you see on a US census that your Swiss ancestor was French-speaking but don’t know his home canton, you could narrow your research to predominantly French-speaking areas. Likewise, an appearance in a historical foreign-language newspapers (more and more of which are being digitized) might be your ancestor’s “tell” that indicates what region of Switzerland he’s from.

Read: How to research ancestors in free historical newspapers

Top Swiss Genealogy Records

Swiss research makes use of many of the same kinds of records as US research:

- civil registrations of births, marriages and deaths

- church records of baptism, marriages and deaths

- census returns

But which record group is most useful will depend on when your ancestor emigrated.

You might find Swiss ancestors who left during or after the second half of the 19th century in the national civil registration system, which began in 1876. Contact your ancestral commune’s civil registry office (Zivilstandesamt in German, bureau d’état civil in French and uffu cio dello stato civile in Italian). Privacy laws restrict access to records fewer than 100 years old to direct-line relatives. And you should remember to submit a request to your ancestor’s commune of citizenship, which is not necessarily the place he lived.

For earlier immigrants, the rich church records of Switzerland o er a huge opportunity to extend a pedigree for centuries. The registers of the Protestant (generally called Reformed or Evangelical Reformed in Switzerland) and Roman Catholic churches often date to the 1500s.

The Mennonite minority, for the most part, did not have this type of recordkeeping tradition because of persecution. But they sometimes show up in the registers of the canton’s established religion, since those records were used for civil purposes.

Church records generally include separate registers of baptisms, confirmations, marriages and burials:

- Baptismal records (of infants) serve as a substitute birth record and generally name the parents and godparents (who were often relatives), as well as the child and baptism date.

- Confirmation records include the date of both confirmation and birth, plus the names of the confirmed person and the pastor and the residence.

- Marriage records give the names of the bridge and groom as well as their residences (but generally not the names of couple’s fathers, as is the tradition in Germany).

- Burial records are substitute death records, but the amount of information varies from additional details such as exact birth date and parents’ names to scanty data that might even only give a guess at the deceased’s age.

The record books also often include separate “family registers” that collate all the pastoral acts of married couple together in one table.

Swiss censuses were taken sporadically on a canton-by-canton basis—some as early as the 1630s. The first national headcount in 1850 was limited to people with rights of citizenship. Later censuses included all individuals, but not all have been preserved or might exist only in summary format. And those that have survived might not be online. (See the next section for a breakdown of FamilySearch’s holdings.)

Finally, Swiss cantons began to issue passports to emigrants at various dates in the 1800s, and many of these records have survived. These registers and files are often detailed, and you can usually find them in canton archives.

Key Online Resources

One crucial online resource, “The Register of Swiss Surnames,” can help solve the “citizenship versus residence” problem. Based on the reference book Familiennamenbuch der Schweiz, the Register lists the surnames for families that held citizenship in each commune. The Historical Dictionary of Switzerland, a nonprofit foundation, purchased the rights to the database, which is based on the third edition of the Familiennamenbuch der Schweiz (published in 1989).

The online database includes nearly 50,000 entries, each listing a surname’s canton/commune as well as the time period when citizenship was obtained there. In some cases, the database also lists a commune of previous citizenship. You can limit search results by place or by time period: families who gained citizenship before 1800, during the 19th century or from 1901 to 1962.

Thanks to FamilySearch’s longstanding microfilming program, many Swiss church registers (and some census records) are now available online. You can browse church record scans at the parish level (though some are restricted for use at Family History Centers), or search large searchable extracted collections of Swiss baptisms, marriages and burials on FamilySearch.org. (These latter collections are also available as “loan items” at subscription databases Ancestry.com and MyHeritage.com.) Likewise, FamilySearch has select online censuses for the cantons of Aargau, Fribourg and Zürich.

As with many things genealogy, the growing online encyclopedia FamilySearch Wiki has several guides and even a number of video tutorials on Swiss research. For just one example, the FamilySearch Wiki article “Switzerland Civil Registration” includes a link to PDF with contact information for civil registration offices nationwide.

For those who are descendants of Swiss Mennonites and struggle with the lack of genealogically useful church records, GAMEO (Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online) helpfully combines data from many family surname history books as well as articles about specific areas around the world from origins to settlements.

Whether you’re the descendant of direct emigrants from Switzerland or “two-steppers” whose families had an intermediate stop in Germany or France, you’ll find there are often bountiful records you can explore that may take your family back 500 years. What you choose to do with all that information—be it yodeling, eating just Swiss cheese or skiing down the Alps—is up to you, but you’ll still be part of that club with Swiss ancestry.

Related Reads

A version of this article appeared in the December 2019 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

ADVERTISEMENT