On the Wales side of the Severn Bridge, a red dragon signals, “Croesa i Cymru — Welcome to Wales.” You’ve entered a small nation approximately the size of Rhode Island, yet one with its own Celtic language, rich heritage and distinctive landscape.

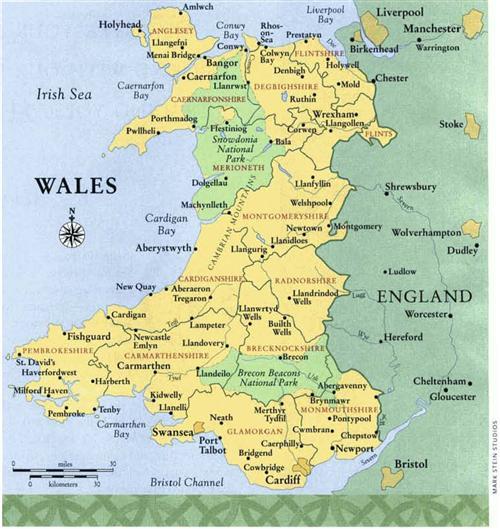

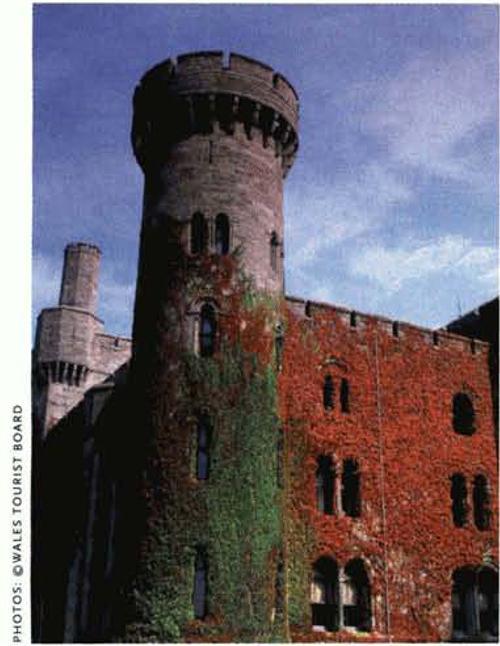

Boasting the cities of Cardiff, Swansea and Newport, South Wales is the most heavily populated part of Wales. It’s dominated by English speakers and industrialization, thanks to King Coal, which the Welsh have mined and exported since the onset of the Industrial Revolution. Highlighted by rich, undulating farmland, West Wales features the counties of Pembrokeshire — long known as “Little England Beyond Wales” — and Carmarthenshire — with its vocal pocket of Welsh-speaking residents whose voting strength helped create the National Assembly in 1999. Scenic Mid Wales, with its small villages, seaside vistas and Welsh-speaking communities, is often unwittingly bypassed by travelers eager to reach Snowdonia National Park, where hikers and sheep punctuate the hulking gray crags. In the late 13th century, the mountainous terrain offered refuge to Welsh rebels fighting Edward I’s army. Though the English king’s mighty fortresses still dominate North Wales, and slate mining has reshaped the land, the region is renowned for its beauty.

Wales’ national anthem, “The Land of My Fathers,” calls this a place “in which poets and minstrels rejoice.” It’s also a place in which many genealogists rejoice. Today, more than 1.7 million Americans claim Welsh roots — and if Wales is the land of your fathers, you can discover their pasts with a few basic steps and resources.

Coming to America

Did you know that the Welsh discovered America well before Columbus sailed the Atlantic? According to tradition, Prince Madog, a son of Owain Gwynedd, king of North Wales, voyaged from Wales to seek his fortune around 1169. Upon his return, he bragged of visiting a new land where the people lived peacefully. Many believe the land was America, and plaques commemorating the discovery have been laid at Rhos-on-Sea in North Wales, Madog’s departure point, and at Mobile Bay, Ala., the prince’s supposed landing site across the ocean.

Despite Madogs momentous discovery, it took 500 more years before the Welsh began immigrating to America. During the 1640s, religious conflict led to the first phase of the English Civil War, which spread into Wales and pitted Protestants against Catholics and Parliamentary supporters against King Charles I’s Royalists, Even after the Patliamentarians defeated the king, and their leader, the Puritan zealot Oliver Cromwell, became lord protector, religious intolerance and repression continued. In Wales, several nonconformist religions held secret services in homes and pubs, and religious groups such as the Independents, Presbyterians, Baptists and Quakers spread throughout the land. Even though the Toleration Act of 1689 allowed people to worship freely, intolerance remained rampant. Not surprisingly, many Welsh citizens found the prospects of religious and political freedom in America difficult to ignore. By the end of the 17th century, some 3,000 Welsh people had sailed to America, where they clustered to continue practicing their individual religions.

In the 1790s, Wales suffered a severe economic and agricultural depression following disastrous harvests and dramatic inflation, which led to another wave of emigration. Sailing from Liverpool, Bristol, Milford Haven, Caernarfon and other ports, thousands of Welsh farmers, weavers, artisans and gentry sought relief in America, where land was abundant and inexpensive, and the economy stable. Others immigrated to Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa.

Between 1815 and 1850, Wales’ population doubled, and Welsh immigration to America soared. The new American residents settled in New York, Pennsylvania, Vermont, Ohio, Wisconsin and Illinois. Some journeyed west to California to take advantage of the 1849 gold rush. Later in the century, Welsh miners and ironworkers flocked to the higher-paying industrial areas of Pennsylvania. By 1900, Welsh settlers had moved into Iowa, Kansas and Missouri, and a large number had migrated to Utah to join the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS). Between 1820 and 1950, more than 250,000 people emigrated from Wales to the United States.

Beginning the Journey Backward

Today, those immigrants’ descendants can learn much about their Welsh roots fight here in America. As with all genealogy research, you should begin at home: Talk to family-members, including distant relatives, who might know about your heritage. And look for names, dates and places in letters, records, the family Bible, photo albums, newspaper clippings and any other documents that may offer clues.

Then, fire up your computer and head over to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ FamilySearch Web site <www.familysearch.org>, where you’ll find an excellent Research Outline. From the home page, click on the Search tab, then Research Helps. Click on the W, and you’ll find a lengthy listing of resources for tracing your Welsh ancestors. Scroll down first to the document titled “Wales Research Outline,” which you can open and review online, or download and study offline. (To read the file offline, click on PDF. And if you don’t have it already, you’ll need to download Adobe Acrobat Reader for free at <www.adobe.com/products/acrobat/readstep.html>)

At first glance, this comprehensive guide may seem overwhelming, but it ultimately will help you decide which ancestor to research and where to find various types of records, including census, church, estate, military, school and probate records. If you’re just starting your Welsh research, begin by reading the introduction and search strategies. If you already know which ancestor you want to research, you can skip ahead to the articles on specific record types.

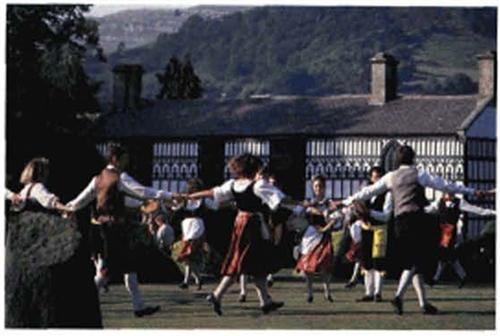

You’ll want to join your local St. David’s Society or the Welsh-American Genealogical Society <www.rootsweb.com/-vtwags>, as well. Both are organizations for people of Welsh descent. Or attend a gymattfa gann, a festival devoted to the singing or” Welsh hymns (in both Welsh and English). There, you can learn more about Wales and its culture, and network with others digging up their roots. You also might subscribe to Ninnau <www.ninnau.com>, a New Jersey-based newspaper full of information not only about Wales, but also about Welsh-American societies, events and genealogy resources. Gather as much information as possible, not just about your particular Welsh ancestor, but also about the nation and its history.

Untangling Welsh Names

Before delving too deeply into your roots, you’ll need to learn about Welsh surnames. Even though their Anglo-Norman conquerors had fixed surnames, the Welsh continued to use patronymics — a naming system in which children take their surnames from their fathers’ given names — in some parts of the country until well into the 19th century. Today, most people use fixed surnames, but some modem-day Welsh are reasserting their national identity by returning to patronymics.

Derived from mab, which is similar to the Scottish mac, the words ap (before a name beginning with a consonant) and ah (before a name beginning with a vowel) indicate “son of.” So Madog ab Owain indicates that Prince Madog was Owain Gwynedd’s son. Likewise, Llywelyn ap Gruffydd, the first and last native prince of Wales, was the son of Gruffydd ap Llywelyn. Indeed, like most medieval Welshmen, Llyweiyn claimed a lengthy pedigree: Llyweiyn ap Gruffydd ap Llyweiyn ab lorwerth ab Owain ap Gruffydd ap Cynan … and so on.

Common Welsh names such as Bowen and Powell reflect patronymic origins. Bowen derives from ab Owain or ab Owen, and Powell from ap Hywel. Price comes from ap Rbys, while Pritchard comes from ap Richard.

Besides using ap and ab, the Welsh also added an s at the end of a father’s first name to reflect kinship. So John’s son adopted the surname Johns or Jones or Jenkins. The same rule applies to Roberts, Williams and Richards. You need to be aware of these variations, and cross-check records to be certain you have identified the correct ancestor.

The Welsh used patronymics in naming their daughters, as well. Fur this reason, many married Welsh women retained their maiden names — a bonus for genealogists. The words verch, ferch, vch, vz and ach indicate “daughter of,” as in Gwenllian verch Rhys.

You’ll also find that mans Welsh names have mutated over time. For example. Llywelyn ap Gruffydd‘s name may appear as Gruffudd, Griffith, Griffiths or even Guto. Madog has become Madoc, Marcdudd has become Meredith, and Evan, Bevan, Jeavons and Ieuan are all variants of John. To bone upon the nuances of Welsh surnames, study Welsh Surnames, The Surnames of Wales or the chapter on surnames in Welsh Family History: A Guide to Research.

Finding Native Ground

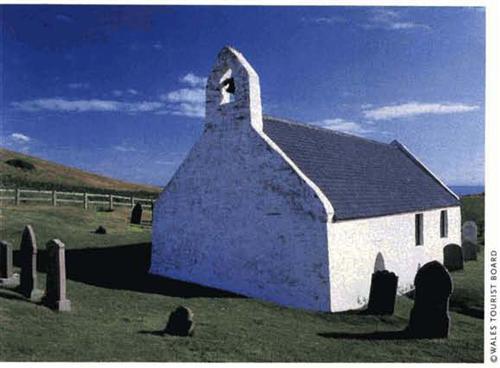

Once you’ve determined your ancestor’s name and any spelling variations, your next step is to locate the town and parish in Wales where the person lived. (You’ll need the parish name because only churches recorded births, marriages and deaths before 1837.) This can be complicated because the Welsh only recently began spelling place names consistently, even in official documents. For example, the town Cricieth sometimes appears in records as Crickaeth, Crikeith, Krickieth or Criccieth ( the most-common spelling nowadays). So as with your ancestor’s name, it’s important to research all known variations of a town or parish name.

What’s more, you’ll sometimes find multiple towns and parishes with the same name. For instance, both Pembrokeshire and Monmouthshire counties have towns called Newport (Trefdraeth in Welsh). There’s also a Newport parish on the Isle of Anglesey. So when you note which town or parish your ancestor was associated with, be sun: to write down the county of diocese in which he belonged as well.

Remember, too, that Wales underwent major structural recoganisation in 1974 and 1996. Counties came and went. The Newport DOW in Monmouthshire was once part of Gwent, and the Pembrokeshire Newport was once part of Dyfed. Most records refer to the pre- 1974 counties, so it’s vital that you identify the correct historical county for your search. Take a look at the LDS Welsh research guide or the Data Wales Web site <www.data-wales.co.uk/walesmap.htm> for help verifying place or parish name.

Documenting Your Past

After you’ve found a name, location and at least an approximate date for your ancestor, it’s time to jump into the records. Ninnau’s genealogy writer. Annie Lloyd, recommends checking census, tax, land, school, and emigration and immigration records, as well as probate files, county and town histories, and any other records for the area where your ancestor lived.

To Starch some of these records, you don’t even have to leave your hometown. The LDS church’s Family History Library (FHL) in Salt Lake City has microfilmed numerous Welsh resources, including census church, civil registration, court, land and military records. From a branch library, or Family History Center (FHC), in your town, you can borrow copies of those microfilms (to find the FHC nearest you, visit <www.familysearch.org/eng/Llbrary/FHC/frameset_thc.fhc.asp>). Search the FHL catalog at <www.familysearch.org/Eng/Librar//FHLC/framcwtThkasp>.

From your home computer, you can search the 1901 census tor England and Wales at the British national archives’ Web site <www.census.pro.gov.uk>. Searching by person, address place or institution is free, but you’ll have to pay a nominal fee to view transcribed data or a digital image of the census page.

Each Welsh county also has a repository of original records (sec Toolkit). Staffed by professional archivists, many of whom know Latin and Welsh and can translate medieval documents, county record offices are indispensable resources. Depending on where in Wales your family originated, you may be able to obtain information by e-mail or snail mail. For example, the Powys County Archives Office, in Llandrindod Wells, offers a research service that costs 15 pounds (about $25) an hour. Its archivists will spend one to two hours searching parish registers, census records or workhouse records. It doesn’t have the staff to do more-detailed research, though; for that, you’ll have to hire another researcher or go to Wales yourself.

If your ancestors lived in North Wales, the Anglesey County Record Office also offers a research service, which costs 10 pounds (about $17) for the first half hour to search a variety of records. The Conwy Archive Service, which covers a ponton of Gwynedd, features an online Ask the Archivist e-mail service <www.conwy.gov.uk/English/2coundl/Iibrary_informat ion_archives/askarchivist/Ec3.html>, and the Gwynedd County Archives has a paid research service, as well. Be sure to check out the Gwynedd County Archives’ searchable online catalog at <wvwv.gwynedd.gov.uk/adrannau/addysg/archi-fau/Rhagorol/cgi-bin/browse_archive.pl>.

The West Glamorgan Archive Service, based in Swansea, has one of Wales’ most extensive collections of documents, including school, hospital, church, police and estate records. Generally, this repository prefers inperson visits, though, so if your ancestors came from South Wales, you may need to take a trip across the pond.

Researching in Wales

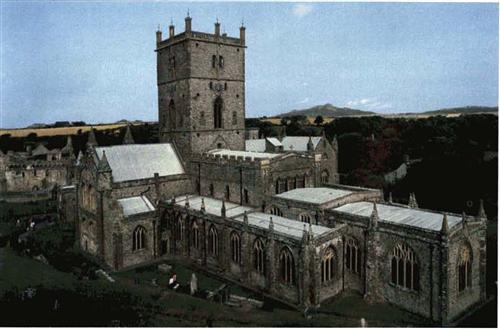

Once you’ve exhausted all research avenues at home, it’s time to visit the land of your fathers (and mothers!). Start planning your trip by contacting the Wales Tourist Board at +44 (0) 8701 211251 or <www.visitwales.com>. When you arrive in Wales, head to The National Library of Wales (NLW) in Aberystwyth <www.llgc.org.uk> or to the county archives office where your ancesrors’ records might he stored. By writing to a repository, you can get a sense of its holdings, and even request copies of official documents. But seeing the documents in person, touching their crisp pages and knowing they pertain to your family’s history adds an emotional dimension to your research.

The NLW is a good starting point for anyone doing research in Wales for the first rime. Here, you’ll find church and school records, wills, manuscripts, maps, photographs and more. You can use the library’s resources for free, but you’ll have to obtain a “reader’s ticket” to view the documents.

You’ll find that most county archives offices hold copies of parish registers and/or bishop’s transcripts (in some cases dating from the 16th century); civil registrations of births, deaths and marriages after 1837; school, hospital, police, probate, maritime, poor law, census and tax records; and trade directories. They also hold copies of regional publications and maps, newspapers and even medieval manuscripts and town charters. The Welsh Archives Council provides details about each county’s record office as well as general policy information and news at <www.llgc.org.uk/cac>.

Be sure to contact the NLW or archives office before your arrival, so you can set up an appointment if necessary, find out if it has the information you seek, and prepare the staff for your visit. Staff are more than willing to work with you. In many cases, they’ll even photocopy information if you can’t go there in person.

Of course, you also need to make time to explore the “old mountainous Cambria, the Eden of bards.” And when you return home, don’t he surprised if you, like so many before you, suffer from hiraeth, a gut-level yearning to return to the land of your forebears. You may find yourself visiting time and again.