Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

In our supposedly classless, egalitarian society, nobility wannabes are fueling a craze for that symbolic representation of a person’s heritage known as a coat of arms, often mistakenly called a “family crest.” Rare is the family historian who doesn’t hope to be descended from an ancestor who was armigerous (that is, according to Merriam-Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary, “bearing heraldic arms”). Most however, are disappointed to find their ancestors weren’t actually entitled with the right to bear arms. Learn what’s history and what’s not when it comes to heraldry.

In this article:

ADVERTISEMENT

What Is Included in a Coat of Arms?

How Are Coat of Arms Passed Down?

ADVERTISEMENT

Can You Design Your Own Coat of Arms?

Heraldry and Coat of Arms Resources

Understanding Heraldry Laws

For starters, a key fact to keep in mind is that coats of arms are not and never have been granted to families. They’re granted to individuals and belong to individuals. Arms can, however, be inherited. According to an informational brochure, “Heraldry for United States Citizens,” published by the Board for Certification of Genealogists (BCG):

- Anyone whose uninterrupted male-line immigrant ancestor was entitled to use a coat of arms has the right to use this same coat of arms.

- If the uninterrupted male-line immigrant ancestor has no such right, then neither does the descendant.

- Anyone who claims the right to arms under European laws must prove the uninterrupted male-line descent.

- As an exception, US citizens can obtain a grant or confirmation of their arms—from the College of Arms in England or other appropriate national heraldic authority in other countries—by payment of required fees.

The brochure also warns, “Commercial firms that purport to research and identify coats of arms for surnames or family names—and sell descriptions thereof under the guise of a ‘family crest’—are engaged in fraudulent and deceptive marketing. The consumer’s best defense is a proper knowledge of the laws of heraldry.”

While the laws of heraldry differ with each country, in some parts of the world it’s actually illegal to display a coat of arms or to use it on stationery or a blazer breast pocket unless you’re the rightful owner. Having the same last name does not entitle you to use the arms. Here in the US, you won’t be thrown in the slammer if you’ve already bought and proudly displayed in your living room what you thought was your family crest.

And yet…you really could be descended from an ancestor who rightfully inherited a coat of arms. To find out, let’s journey back in time to learn how coats of arms originated, what they mean and how to discover if any of your ancestors had a legitimate claim to them.

The History of Coats of Arms

Coats of arms developed in the 12th century as a means to identify armored knights during tournaments and on the battlefield. Any fighting man owned a sword and shield, carried a banner and wore a helmet, all of which his son would one day inherit. Behind a closed helmet, it was impossible to tell one man from another except by the decoration of his shield and banner and the ornaments on the helmet. The term “armory” relates to the emblems; “armoury” to weapons. Warriors also wore a decorated “surcoat,” or fabric overlay, over their armor—hence the term “coat of arms.”

Over time, these emblems became a means of personal identification, allowing an owner to mark items of value, such as silver, and to engrave bookplates and stationery. With their growing use and popularity, disputes arose over who could legitimately use a particular design. In 1484, Richard III established the College of Arms and assigned heralds to visit households across England to record each owner’s design. These “visitations” were made between 1530 and 1686.

Early on, arms were the signs of nobility and rank, but eventually practically any man who owned land also had the right to bear arms. Thus arms became a symbol of the gentry, and it became fashionable and prestigious to descend from a line with armigerous ancestors. Each country has its own laws as to who could inherit the arms. Commonly, the symbol was passed down from eldest son to eldest son in an unbroken male line. Other sons, and even daughters, might use variations of the main emblem, adding specific symbols—or cadency marks—to indicate birth order, illegitimacy and adoption.

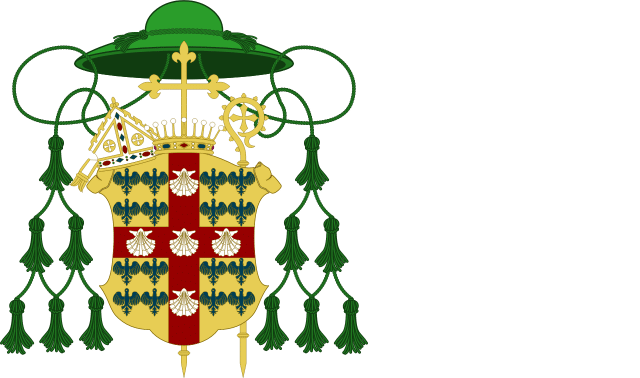

What Is Included in a Coat of Arms?

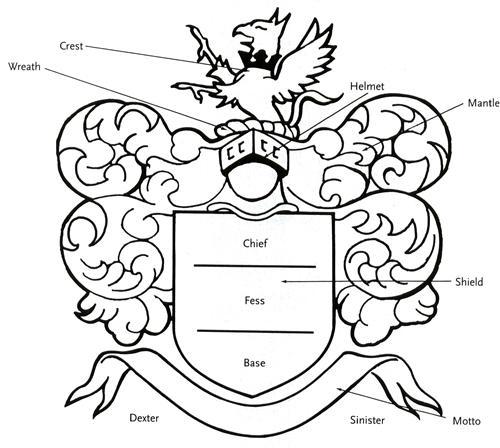

Although we commonly refer to it as a “coat of arms,” the proper term is a “heraldic or armorial achievement.” A complete heraldic achievement is made up of a crest, wreath, mantle, helmet, shield and, although not essential, a motto. There may also be supporters to hold up the arms and a compartment (or ground) for the supporters to stand on.

Crest

The crest is a figure or symbol attached to the top of the helmet. Animals such as lions, tigers and bears are commonly used as crests, but you’ll also find boars, foxes, horses, birds, insects, reptiles and mythical animals such as unicorns and dragons. These may stand alone or be combined with other symbols, such as flowers, trees, wreaths or swords.

Helmet

The helmet supports the crest. Positioning of the helmet represents rank. For example, a helmet facing forward with the visor opened means a knight, while a helmet facing side-ways with the visor closed is for a gentleman.

Wreath

The wreath, originally a piece of twisted silk showing two colors, is at the base of the crest and was used to attach the mantle to the helmet. Typically, the wreath shows six twists of alternating colors of the shield.

Mantle

The mantle (or lambrequin), originally a piece of fabric attached to the knight’s helmet to protect him from the sun’s heat, fills out the design. It represents the fabric being slashed in battle.

Motto

The motto is a ribbon below or over the achievement, which carries a statement of fact, a hope or battle cry.

Shield

The shield is the most important part of the coat of arms. It is made up of a field (the surface or background) and the charges (the symbols on the field). If the achievement belongs to a lady, the field will be diamond-shaped (a lozenge) rather than a shield. The field contains many different ordinaries and sub-ordinaries—geometric bands or shapes that divide the field, such as crosses, chevrons and stripes. The shield can become quite complex, with more terms than you’d care to know and remember. In describing a coat of arms (known as blazoning), the field is always stated first and the components are described as being dexter (right side of the wearer), sinister (left side of the wearer), chief (top), fess (middle) and base (bottom).

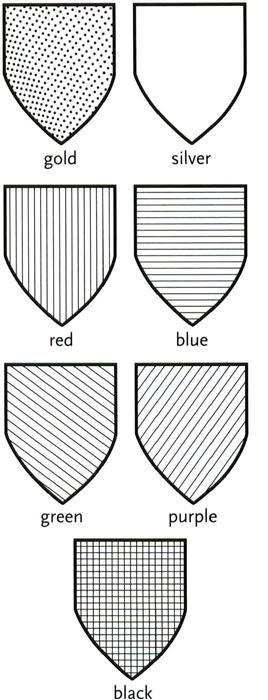

Tinctures

Tinctures—the colors, precious metals and furs on a coat of arms—are also represented by words and patterns. The two metals are gold (or) and silver (argent); the colors are red (gules), blue (azure), green (vert), purple (purpure) and black (sable); the furs are ermine and vair. In black-and-white illustrations specific conventions are used to indicate the colors, metals and furs. The written description (blazon) might read, “Quarterly gules and/or, in the first quarter, a five-point mullet argent,” which means the shield is divided into red and gold quarters, and in the first quarter, or the upper left as you look at the shield, is a silver, five-pointed star.

Hatchment

Another aspect of heraldry is the funeral achievement or hatchment. According to Theodore Chase and Laurel K. Gabel in “Headstones, Hatchments and Heraldry,” in Gravestone Chronicles II: More Eighteenth-Century New England Carvers, a hatchment is the “painted coat of arms associated exclusively with death, funerals and mourning…. They are often set in decorated frames that depict mortality symbols such as hourglasses, skulls or bones” against a black background. These funeral hatchments “indicated to the viewer the gender, marital status and often the family position of the deceased” and also may be found carved on colonial New England and Virginia tombstones. According to Chase and Gabel, “In the United States, having an heraldic tombstone with a death date prior to 1750 is in fact sometimes considered proof of a legitimate right to bear arms.” Chase and Gabel are trying to find and record all the pre-1850 armorial tombstones in the United States. For information about the project, visit the Association for Gravestone Studies website.

Sharon DeBartolo Carmack

How Are Coat of Arms Passed Down?

Contrary to popular notion, coats of arms don’t go with surnames. Think about how confusing it would be if everyone in the same family had the exact same arms. Instead, a person would be granted the right to bear a particular coat of arms, a right that passed down to his male descendants. In England and Scotland, an eldest daughter could inherit arms in the absence of male heirs; and wives and daughters could bear modified versions of the arms. A heraldic authority, such as Britain’s College of Arms, regulates the granting of arms.

Coats of arms aren’t just pretty pictures. Their symbols can indicate profession, order of birth, rank, ancestry and more. Though the terms coat of arms and family crest are often used interchangeably, the former is just the shield and the latter is attached to the top of the shield (turn the page to see a breakdown of the parts in a heraldic achievement). When displaying the full arms isn’t practical, just the crest might be used.

But what about all those coat of arms tchotchkes? Buyer beware if the seller of a heraldic trinket tells you it’s your family’s. How does he know? Did he trace your lineage? Because coats of arms are granted to individuals, not families, this claim is probably false. Even if the arms were granted to someone named Fred Smith, and you’re a Smith, those aren’t your arms unless you can prove you’re a male-line descendant of Fred. Dozens of arms might be registered to people of the same surname, and your task is to discover which one—if any—is correct for your ancestral line.

Even if you didn’t inherit your ancestor’s coat of arms, heraldry still can come in handy for your genealogy. For it to help you, though, it’s important to understand the basics of how heraldry works. An excellent book to start with is An Heraldic Alphabet by J.P. Brooke-Little, Clarenceux King of Arms (Robson Books). This dictionary of heraldic terms can help you decipher documents and understand the meaning of heraldic imagery.

Can You Claim a Coat of Arms?

It seems the coat of arms craze isn’t just a modern fad. Colonial ancestors, many of whom were not eldest sons and stood no chance of inheriting land or a title in Europe, adopted heraldic achievements as a status symbol once they had settled and made a name for themselves in America, whether they were entitled to arms or not. Between about 1750 and 1775, many wealthy colonial families hired painters specializing in heraldic arts to create a coat of arms for them. Some of these may have been legitimately registered with the College of Arms in England; others, not.

So how do you determine if one of your ancestors had a legitimate right to a heraldic achievement? You must prove direct lineage to the person the honor was granted to. Here are several resources you can research in to see if your family can claim a coat of arms.

Tip: As you research your family history, you may encounter a published genealogy on your ancestry that reproduces a coat of arms or “family crest,” but be extremely cautious of these and research for yourself the accuracy of its use.

Ordinary of Arms

For arms without a name, look up the coat of arms or its blazon in a book called an ordinary of arms (essentially, a dictionary of blazons). Crozier’s General Armory is on the free Internet Archive, and check large research and university libraries. Older books, such as the 1902 Some Feudal Coats of Arms from Heraldic Rolls, 1298-1418, by Joseph Foster, will stretch further back in time.

Peerage

Next, look up the name in a “peerage,” or a genealogical reference to aristocracy and nobility. Burke’s Peerage is a publisher founded in 1826 with the guide A Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Peerage and Baronetage of the United Kingdom. The publication was updated sporadically until 1847, then annually, and more titles were added for countries around the world. Find Burke’s Peerage in large libraries and search for names on the publisher’s subscription website. Editions from 1865, 1881 and 1884 are on Ancestry.com, as are other peerage books (search the card catalog for peerage). Also try Debrett’s Baronetage, Knightage & Companionage 1893 edited by Robert H. Mair.

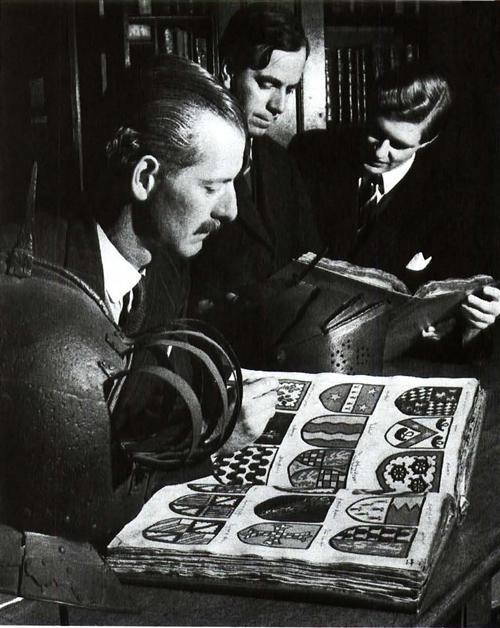

Roll of Arms

A “roll of arms” is a wonderful resource with images of arms. These rolls were sometimes a listing of all the knights, and later armigerous persons, in a given area. Other times they were lists of the participants in a tournament. Amazing heraldic rolls commemorate funerals or large state functions, with heraldry as a way to show who was in attendance. One of the most famous rolls is the Codex Manesse, created in the first half of the 1300s for the Manesse family. It’s a book of poetry and the images are of the poets, most of whom are shown with coats of arms. Luckily for us, this book is free online and you can see its 137 magnificent images for yourself. Search online for a family name and “roll of arms” and look for the book A Roll of Arms Registered by the Committee on Heraldry of the New England Historic Genealogical Society.

Heraldic Pedigrees

You’ll also find ornate heraldic pedigrees, mainly for royalty. Relatives would commission these to show their importance and prestige. One word of caution: Don’t assume these heraldic pedigrees (or any other pedigree, for that matter), is 100% accurate. A king would be motivated to prove his descent from certain historical figures to assure the populace he ruled by divine right.

Tip: The British College of Arms offers fee-based research services to those wishing to learn about their heraldic connections.

Shannon Combs Bennett

Can You Design Your Own Coat of Arms?

You may certainly design your own coat of arms, and there’s even websites to help you do so (see below). You can also have it registered with the American College of Heraldry, which recommends you follow these guidelines when designing your own:

- Make sure your design is unique. Check other crests to make sure you are not infringing on someone else’s design.

- Keep the design simple; the idea is to have it be easily recognized as yours and remembered.

- If possible, design your arms in the style of your ethnic background. This will require you to research that country’s heraldic style.

- Don’t use symbols that have particular meaning in heraldry, such as crowns, coronets and supporters.

- Look for symbols that represent you as an individual, such as your occupation or hobby.

Just know that the United States has no legal heraldic system, so there’s nothing official about assuming arms; An American Heraldic Primer offers more information.

Coat of Arms Design Websites

Heraldry Designer by The Dominion of Thorne

Sharon DeBartolo Carmack

Heraldry and Coat of Arms Resources

Websites

The American College of Heraldry

Heraldaria (Heraldry for Genealogy Nobility Surnames of Hispanic Origin)

Institute of Heraldic and Genealogical Studies

Office of the Chief Herald, National Library of Ireland

The Royal Heraldry Society of Canada

Societas Heraldica Scandinavica (Heraldry Society of Scandinavia)

And just for fun, this website explores the real history, heraldry and family trees that inspire Game of Thrones. (Warning: contains spoilers.)

Books

The Art of Heraldry: Origins, Symbols and Designs by Peter Gwynn-Jones (Barnes and Noble)

“The Coats of Arms Craze” in Milton Rubincam’s Pitfalls in Genealogical Research (Ancestry)

A Complete Guide to Heraldry by Arthur Charles Fox-Davies (Wordsworth Editions)

Design Your Own Coat of Arms: An Introduction to Heraldry by Rosemary A. Chorzempra (Dover Publications)

“Headstones, Hatchments and Heraldry, 1650-1850” in Theodore Chase and Laurel K. Cabel’s Gravestone Chronicles II: More Eighteenth-Century New England Carvers and an Exploration of Gravestone Heraldica (New England Historic Genealogical Society)

Heraldry: A Pictorial Archive for Artists and Designers edited by Arthur Charles Fox-Davies (Dover Publications)

The Oxford Guide to Heraldry by Thomas Woodcock and John Martin Robinson (Oxford University Press)

The Symbols of Heraldry Explained by Heraldic Artists Limited

Genealogy References

Burke’s Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Landed Gentry: Including American Families with British Ancestry, 3 vols., by Sir John Bernard Burke (Burke’s Peerage). (Burke compiled numerous volumes of heraldic history besides these.)

Founders of Early American Families: Emigrants from Europe, 1607-1657 by Meredith B. Colket Jr. (General Court of the Order of Founders and Patriots of America)

New England Historical and Genealogical Register. See volumes 82 (Apr. 1982); 86 (July 1932); 106 (July and October 1952); 107 (January, April, July and October 1953); 112 (July and October 1958); 122 (January, April and July 1968); 125 (July and October 1971); 133 (April 1979); 145 (October 1991); and 146 (July 1992).

Versions of this article appeared in the August 2000 (Carmack) and January/February 2018 (Combs-Bennett) issues of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated September 2024.

Related Reads

FamilyTreeMagazine.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for site to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to affiliated websites.

ADVERTISEMENT