Death notices. Obituaries. Necrologies. No matter what you call them, genealogists seek them out. When found, these notices can either be a source of treasure or a sad disappointment. Anyone used to the lengthier, family-written obituaries that appear today in online newspapers and funeral home websites will be amazed at what passed for a notice of death 50 or more years ago.

However, even those scanty notices from long ago can be valuable for your research. Here’s what you can expect to discover in old obituaries (and four sources where you should look for them).

4 Sources for Historical Obituaries

1. Home sources

Start searching for obituaries in home sources, especially scrapbooks. In the 19th and 20th centuries, scrapbooks were popular and used for collecting flowers, postcards and poems. But they often also contained newspaper clippings, including obituaries. Though they may lack source information and dates, these clippings can be key to discovering your ancestors’ obituaries.

When you take a first look at an old family scrapbook, you might not recognize all of the names.

But make sure you still transcribe, scan or photograph all the news articles anyway. You may later recognize the notice’s value later, once you’ve learned additional family information (such as a woman’s married or maiden name).

If your relatives didn’t keep scrapbooks, check with the local historical society, which might have one belonging to other locals.

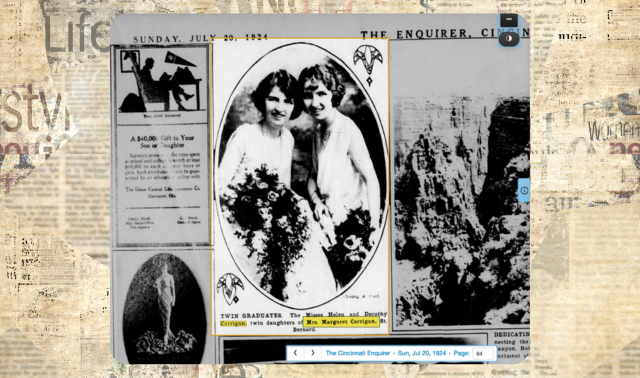

2. Scanned newspapers

Digitized newspapers are available in many places, including on websites such as:

- the Library of Congress’ free Chronicling America site

- the free Google News Archives

- Newspapers.com, an Ancestry.com-owned subscription site

- GenealogyBank, a subscription site owned by online database NewsBank

All of these sites include information on the newspaper’s edition, plus day/date of publication. If you know a person’s approximate death date, consider searching for a date range (such as 1907–1920) on sites like Newspapers.com. Current newspapers themselves may keep an online archive of the past year or so of their obituaries, charging a small fee for an older death notice.

Note that searching old newspapers for obituaries in hopes of finding an organized column of death notices will probably be futile. Not only were obituaries not all grouped together, but they could be found throughout the publication: one in the Social Notes, one in the classifieds section and another squeezed into a small space under an advertisement. Instead, search a document for the name of the deceased or his relative, or perhaps the name of the community he lived in.

Occasionally, a person might not be mentioned in the newspaper at the date of his death. But relatives might have placed a memorial for him (usually in the classifieds section) on an anniversary of his death, so be sure to check later dates.

3. Crowd-sourced websites

Many people now post obituaries (along with burial marker photos) at the popular website Find a Grave, which hosts user-created online memorials. You may also find obituaries on relatives’ social media profiles.

Likewise, researchers may upload obituaries (along with other documents) to online family trees on databases such as Ancestry.com, FamilySearch and MyHeritage.

In these cases, make sure you can see the actual newspaper clipping yourself. Otherwise, you are at the mercy of someone else’s transcription.

4. Search engines

Make liberal use of your general search engine (like DuckDuckGo or Google) to seek out obituaries. Search for a person’s name in quotation marks (“John Elliott Stubenhaver”), and you may find obituaries in places you never expected—for example, church newspapers and annual reports.

An article that clearly includes your ancestor’s name may not come up with your search results, which means you’ll have to be cagier. In other words, you’ll want to try both “J. E. Stubenhaver” and “Mr. Stubenhaver,” plus all the varieties of misspellings that you have come across in your research.

Despite being difficult to find in other records, women’s maiden names were often given in obituaries. So when looking for Tabitha Hillyer (née Browning), you can search for both “Tabitha Browning” and “Mrs. Henry Hillyer.” Likewise, don’t forget to search the person’s name with words such as Grandpa or Aunt, in case full names weren’t known to the person who wrote the obituary.

Interpreting Details in Obituaries

Sometimes, a death notice contains very little information. For example: “Thomas Smith died last week. He suffered from a complication of diseases,” which provides no date, identifying information or names of parents or survivors.

But editions in the days or weeks before a death might give more information on what led to the person’s end. “Rudolph and Fritz Byer are down from Seattle to visit their father who has been suffering from typhoid” gives several clues to “Mr. Byer’s” later death mention.

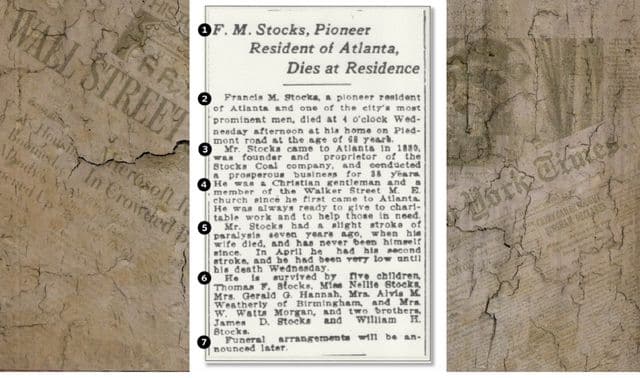

In the best cases, an obituary will provide:

- place and date of birth (or sometimes the death age in exact years, months and days)

- parents’ names

- siblings’ names

- information about military service and/or occupation

- details education, religious affiliation, groups and lodges, and even political party

Each one of these facts can direct the researcher elsewhere: military records, church histories, colleges, fraternal organizations, etc. Even a detail such as “Elizabeth settled on the old Kincaid homestead” provides a starting place to search a plat map.

Older obituaries often list pallbearers, and many times these were nephews or brothers-in-law of the deceased. Some localities of the country also had “flower girls,” the women who carried bouquets of donated floral arrangements to the casket or altar. Still others listed out-of-towners who attended funeral and burial services. All of these lists can be mined for relatives.

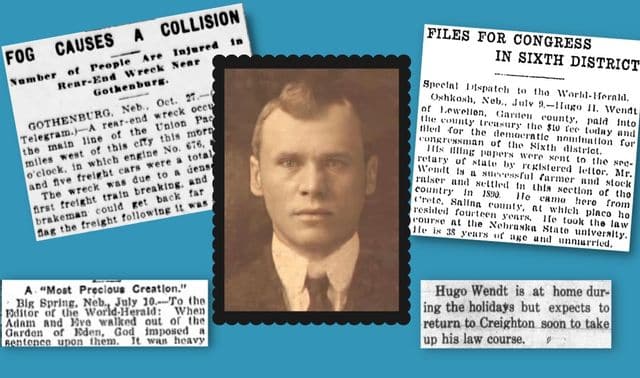

Geography clues

Some death notices tell of the geographical moves during a person’s life. Perhaps an ancestor:

- was born in Pennsylvania

- moved to Ohio when a small child

- went to live with an aunt in Indiana to attend high school

- homesteaded a farm in Oregon

In that case, you would want to follow up with census records, then check newspapers from each of these places for death notices. Newspapers sometimes reported on deaths of former residents. So even if your cousin died in California, there might be an obituary for him in Arkansas, where he was born and still had living relatives.

Let’s look at an example. In 1966, the St. Joseph (Mo.) News-Press reported on the death of a man in Kansas:

“Doctor Schirmer, a native of Chicago, came here with his parents, the late John Henry and Marie Schulz Schirmer, when he was eight years old. His brother, Carl O. Schirmer, who owns and operates Schirmer Pharmacy at 6104 King Hill Avenue, was two years old at the time.”

In just that small paragraph, we find the names of the deceased’s parents, information about a living brother and the approximate date of the family’s migration from Illinois to Missouri.

Sensitive details about cause of death

Though there was stigma about suicide (and the details can be emotionally difficult to read), obituaries can still provide valuable information about the person’s life, circumstances and health history.

In earlier times, suicides were reported in a straightforward manner, with a great deal of sensitivity towards the deceased (or, at least, to the surviving family). For example, the St. Joseph (Mo.) News-Press attributed Arthur Bryant’s 1901 gunshot suicide to his being “temporarily crazed as a result of the sunstroke suffered yesterday.” Likewise, the same paper said Samuel Wallace’s 1911 death by carbolic acid was caused by “despondency brought on by ill health.”

Other publications took a different, more graphic approach. The Savannah (Mo.) Reporter reported on April 11, 1913, that John Wandfluh “committed suicide at his home one mile from Lenox, Iowa, Tuesday morning about 10 o’clock by shooting the top of his head off with a shot gun because he was despondent.” The paper goes on to add more context, informing the reader that Wandfluh’s father failed in business and his brother spent a year in county jail for debauchery and public drunkenness.

The Bedford Iowa Times added even more particulars:

“When Mrs. Wandfluh heard the shot she went to the room where her husband was. He was sitting in a chair, the gun dropped down between his legs, the top of his head blown off. Nearby was a broken bottle, which is said to have given forth an odor that told the story of the conduct of its possessor.”

While colorful, you should be skeptical about such reporting, since (even in times past) the press enjoyed eye-catching stories and embellishment.

Obituaries for women

Women often fared worse than men in the length and detail of their memorials. “Mrs. T. M. Appleman wife of J. R. Appleman died last Monday,” announced the El Dorado Kansas Republican of December 12, 1890. No maiden name is given, nor are survivors, details of age or cause of death.

Women’s obituaries also reflected their more limited social mobility. Whereas a man might have been elected to public office, been prominent in church affairs, farmed 180 acres and stayed a staunch Republican (any of which might have been mentioned in his obituary), women generally were memorialized with a brief sentence: “She was a faithful wife, a loving mother and a kind neighbor.”

Look to a woman’s siblings for more information about her. Surviving brothers can give you a maiden name (though the listing could include half-brothers who had different surnames). Sisters may be mentioned only by their husbands’ names, but obituaries for their husbands (i.e., your ancestor’s brothers-in-law) might include their maiden names.

Taken together, information in siblings’ obituaries can be combined to establish information about the whole family. So even if your ancestor’s obituary is missing, those of her parents, sisters and cousins can be useful. For example, a grandmother’s death notice might mention that “her son George died last month,” which will direct you to George’s obituary as well.

Obituaries for people of color

In earlier times, people of color (in particular) might not have received obituaries. Indeed, they may have only been mentioned if their deaths were violent or part of some disaster. And even then, they might only be known as “Grandma Washington” or “Pedro, a dock worker.”

In some cases, a person of color might not even be named in her own obituary. The St. Joseph (Mo.) News-Press ran this obituary in 1909 for an African American woman:

“A negress believed to be one hundred years old, died at 8:30 o’clock last night at the home of Henry Willis, 1422 North Eighteenth Street. ‘Aunt Ellen,’ as she was known, was a relic of slave days and was owned and brought to St. Joseph by the late Mrs. Sidney Harris, mother of Mrs. Zelda Forsee. She was later owned by Mrs. John Corby, with whom she lived for a number of years after the Civil War. According to several of the older negro residents, ‘Aunt Ellen’ was the oldest colored woman in St. Joseph. She was a member of the Catholic church.”

This notice for “Aunt Ellen” gives more details than for most African Americans at the time. But the obituary allocates more space to her “owners” than to her own relations or work, and the notice failed to mention her definitive name or age.

To find a person of color’s obituary, consider researching funeral homes that worked with that specific community. Then search for your ancestor among records from that organization.

Obituaries for children who died young

A toddler might only be mentioned as “infant child of” its parents. Obituaries often lack gender or name, though the copy might describe its “cherubic” ways or “precocious nature.” With good luck, however, a relative or researcher might come across loving details of even a child.

For example, the death notice of little Mattie Tayloe, in the January 8, 1885, issue of Miltonvale (Kan.) News:

“[The doctors] pronounced her taken with Membraneous croup and hopeless, and soon her young life sped away. On Monday evening about five minutes before her departure, she asked her papa to carry her, and as the hands upon the dial pointed to the sacred number (7), suggestion of her perfect life, from off his paternal bosom the angels raised her to the cherub car and the winged steeds bore her home.”

Troubleshooting Errors in Obituaries

Newspapers editions were often put together in a hurry. Information—particularly in obituaries—came to editors through a written note, a visitor stopping by or a telephone call. Then they jotted down and changed to linotype thereafter. As a result, the information that appears in an obituary may not have been reported accurately. In the print process, numbers could be transposed and place names misspelled.

In addition, the printed information (even if it correctly reflects details given by the informant) might include factual inaccuracies. Obituaries are not firsthand sources—they relied on data provided by someone adjacent to an event. For example, the brother of a deceased person may have thought the deceased was born in Alabama, but him thinking that doesn’t make it so. Just as with a death certificate, the information in obituaries is only as accurate as the information-giver.

Misinformation doesn’t necessarily come from the reporter’s or informant’s ignorance, however. Sometimes individuals fibbed dates for other reasons, and those alterations were reflected in their obituaries.

In one instance, a 1911 church newspaper obituary gave Emma (Bricker) Howland’s birth year as 1848. Someone clipped the obituary and sent it to Howland’s sister, who wrote to the paper insisting that Emma was born in 1842, not 1848: “This is a true statement and will not brook denial. Emma’s age at her death was 69 years, 6 months … we must not deny.” As it turned out, the difference came from Howland herself: She hadn’t wanted people to know that she was six years older than her husband.

Misleading details

Though not necessarily errors, details in other obituaries might be misleading. Families often listed stepchildren and foster children simply as “children,” complicating matters. Be on the lookout for multiple marriages as well. Since the surviving spouse may not necessarily be the birth parent of all children listed.

Shifting cultural practices might also affect how you should read more-recent obituaries. As more women keep their birth surnames after marriage (or hyphenate their names with those of their husbands), surname practices change for the children involved, making it harder to make assumptions about family structure. Also note that some people now include pets in their obituaries, so watch out for “Waldo” and “Fluffy,” who might well be dogs instead of humans.

If you’re having trouble finding your ancestor’s obituary, remember that it’s possible he didn’t have one. Poverty, social position, race and religion sometimes kept people from having any death notice at all.

Or, perhaps, your ancestor died at the same time as several others. During epidemics, such as the “Spanish flu” outbreak of influenza in 1918, there may have been too many deaths to note. In cases like these, newspapers may have printed “burial applications” instead of obituaries, listing the names, ages and causes of death of people to be legally buried by local funeral homes or sextons.

Whether your ancestor’s death notice is one sentence or several pages, each is another piece of secondary evidence for you to evaluate and explore. Verify the information you find in death notices using death certificates, census records, family Bibles and other documents.

Want to broaden your search? Read the current daily obituaries in your hometown or another area of interest to potentially connect with descendants of mutual ancestors—or to think about your own mortality. As the saying goes, “When I get up in the morning, I read the obituaries. If I don’t see my name, I go make breakfast.”

Related Reads

A version of this article appeared in the May/June 2020 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: May 2025