Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

When it comes to cousinhood, the relationship possibilities are endless. Your number of grandparents doubles with each generation. Count back 10 generations, and that’s 2,046 total ancestors, which means the cousin potential is exponential. You could have millions of them: fourth cousins, second cousins three times removed, tenth cousins twice removed … we could go on.

And with DNA testing, Facebook, online family trees and message boards that connect you to new cousins every day, you’re bound to get curious about exactly how you’re related. Good thing we’re here with this guide on figuring out what kind of cousins you are, based on degrees of separation from shared ancestors.

In This Article

What makes someone a cousin?

First cousins

Second cousins

Third cousins

What is a second cousin once removed?

Double cousins

“Kissing” cousins

Collateral degree calculation

How to figure out what kind of cousins you are in 4 steps

Determining cousin relationships with DNA matches

Share this slideshow with your genealogy group!

Related Reads

What makes someone a cousin?

The simple fact that you share an ancestor with that person. But to understand the intricacies of cousin relationships, you have to get this: Your ancestors are only the people in your direct line: parents, grandparents, great-grandparents and so on. Your ancestors’ siblings are aunts and uncles (no matter how many greats you add)—not ancestors.

Just about any other blood relative who isn’t your sibling, ancestor, aunt or uncle is your cousin. To determine your degree of cousinhood—first, second, third, fourth—you need to identify the ancestor you share with your cousin, and how many generations separate each of you from that ancestor.

First cousins

Your first cousin (sometimes called a full cousin, but usually just a cousin) is the child of your aunt or uncle. The most recent ancestor you and your first cousin share is your grandparent. You typically share 12.5 percent of your first cousin’s DNA.

Second cousins

Your second cousins are the children of your parents’ first cousins. Take a look at your family tree, and you’ll see that you and your second cousins have the same great-grandparents. You typically share 3.125 percent of your second cousin’s DNA.

Third cousins

Of course, cousinhood doesn’t end there. You have likely also heard the term third cousin and wondered what that means. For third cousins, great-great-grandparents are the most recent common ancestor, and you share .781 percent of your DNA. You get the picture.

What is a second cousin once removed?

If you’re puzzled over the expression “second cousin once removed” or “twice removed,” you’re not alone. Luckily, the answer is simple: All cousins share a common ancestor. Your “degree of cousinhood” (second, third, fourth) depends on how many generations back that common ancestor is. Knowing this, you can make your own cousin calculator.

Take your first cousins, who you know are your aunts’ and uncles’ children. You all have the same grandparents. Your second cousins share a set of great-grandparents with you, your third cousins have the same great-great grandparents, and so forth. So your granddaughter and your sister’s grandson would be second cousins, for example—they have two generations between them and the common ancestor (your parents).

How to calculate cousin removes

“Removes” enter the picture when two relatives don’t have the same number of generations between them and their most recent common ancestor. One generation difference equals one remove.

Let’s go back to the previous example—say your granddaughter has a son. He has three generations between him and the common ancestor (your parents), but your sister’s grandson still has only two generations in-between.

So they would be second cousins, but once removed. Likewise, your grandparents’ cousins are your first cousins twice removed because of the two-generation difference from you to your grandparents. Your great-great-grandparents are still the common ancestor.

Finding a recent common ancestor

First identify the most recent common ancestor for the two relatives in question. Then find each relative’s relationship to that ancestor on the sides of the chart; where the row and column meet, you’ll find their relationship.

Allison Dolan

Double cousins

You may have heard people say they’re double cousins. That’s a special cousin category for the offspring of brothers- and sisters-in-law—for example, your sister weds your husband’s brother. Instead of sharing one set of grandparents, as first cousins do, double cousins share both sets of grandparents. As you might expect, double cousins have more DNA in common than typical first cousins—about 25 percent.

“Kissing” cousins

Despite how it sounds, a kissing cousin isn’t a cousin you marry. Rather, it’s any distant relative you know well enough to kiss hello at family gatherings. Now we’re begging the question: How close of a cousin is too close to wed? States have different laws governing consanguineous marriages (and we’ve heard all the jokes, so just stop right now). It’s best to ask a lawyer about statutes for the state in question.

And while we’re on the topic: Due to limited mobility in our ancestors’ day, most of us have instances in our family trees of cousins who married, whether knowingly or unknowingly. That means you can be related to the same person in multiple ways.

Someone you’re related to by marriage, rather than by blood, isn’t your cousin. You might be in-laws, or your relationship might not have a name other than (we hope) good friends. You can read more about collateral degree calculation—oops, we mean family relationships—in Dozens of Cousins by Lois Horowitz (Ten Speed Press) and Jackie Smith Arnold’s Kinship: It’s All Relative, 2nd edition (Genealogical Publishing Co.).

Tip: Remember that the shared DNA numbers shown in our chart are averages. Due to the random way DNA is inherited, it’s possible you don’t share any DNA with a given relative beyond about second cousins.

Collateral degree calculation

Anthropologists call the process of figuring out cousin relationships “collateral degree calculation” (don’t worry, we won’t spring that term on you again). Multiple removes and degrees of cousinhood can get complicated, but you don’t have to be a scientist to get it right. Our chart will help straighten out your cousin confusion; just follow the instructions for using it. For example, to figure out how you’re related to your great-great-grandmother’s sister’s son, first determine the ancestor you share with him: your third-great-grandmother. Find her on the chart, then count down one generation for the sister and one more to the sister’s son. He’s your first cousin three times removed.

Diane Haddad, from the July/August 2017 issue of Family Tree Magazine

How to figure out what kind of cousins you are in 4 steps

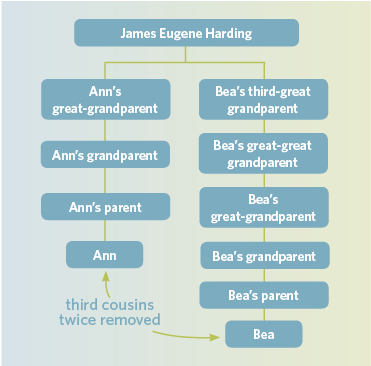

Meet Ann and Bea. They met at a genealogical society meeting and are trying to determine how they’re related. Can you help them figure it out?

1. Identify the most recent ancestor.

For Ann and Bea, let’s say it’s James Eugene Harding, born in 1850.

2. Determine each person’s relationship to that ancestor.

What kind of cousins you are depends on the most recent ancestor you share with your relative. First cousins share grandparents. Second ones share great-grandparents, third ones share great-great-grandparents, and so on. Add a “great” for each generation away from the common ancestor.

Ann and Bea determine that James is Ann’s great-great-grandfather and Bea’s fourth-great-grandfather.

3. “Equalize” the cousins at the level of the one closest to the common ancestor.

Equalizing the them at Ann’s level would make them third cousins.

4. Add one “removed” for each difference in generations between the them.

Two “greats” separate Ann and Bea—they’re third cousins twice removed.

Things get trickier when you’re talking about being “removed.” Each “removal” signifies one generation of difference between the two. Your first cousin’s child is your first cousin once removed. Your first cousin’s grandchild is your first cousin twice removed.

Shannon Combs-Bennett, from the May/June 2015 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

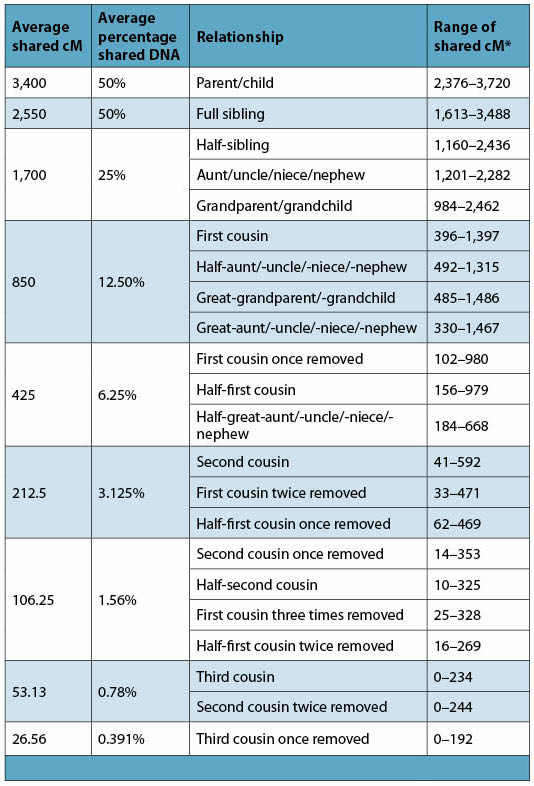

Determining cousin relationships with DNA matches

Have you ever been curious about how to determine relationships from shared DNA? Autosomal DNA testing companies report the amount of DNA you and a match share to give you an estimate of your relationship. The chart below expands on those estimates (measured in centimorgans, or cM) to help you more figure out how you and a match are related. Use this chart to learn how to use shared DNA to determine relationships with matches.

In the “Average Percentage” columns, find the number nearest to your shared cM. The Relationship column shows the likely relationship(s) based on that amount of DNA. Other relationships are possible, though, as shown in the “Range” column. For example, if you share 900 cM with someone, possible relationships include first cousins, half-aunt/uncle and half-niece/nephew, great-grandparent/great-grandchild, and great-aunt/uncle and great-niece/nephew.

The closer the relationship, the more useful the match will be in your genealogy search. For example, second cousins share great-grandparents. If you have a second-cousin match, find the person’s great-grandparents in his family tree. Then research that couple’s descendants—one of them may be your birth parent.

Note that a given relationship, such as first cousins, can share varying amounts of DNA because of recombination (“shuffling” that occurs at conception). You usually share about 850 cM with a first cousin, but that number could be as low as 396 or as high as 1,397 cM. Likewise, a single shared-cM value could indicate a variety of relationships. For example, 1,200 shared cM could indicate a first cousin, great-grandparent, grandparent, or great-niece. You’ll need more information to sift through these similar values.

In addition, note that different DNA testing companies have different methods of calculating and presenting amounts of shared DNA. As a result, you and a match may share different amounts of cM when comparing at different services.

Family Tree Editors

Share this slideshow with your genealogy group!

Related Reads

FamilyTreeMagazine.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program. It provides a means for this site to earn advertising fees, by advertising and linking to Amazon and affiliated websites.