The late 1800s and early-to-mid-1900s can be a challenging era for US research: The legacy of slavery lingered. Government birth records were spotty. Immigration was at its peak. And the 1890 census was almost entirely lost. Fortunately, a government agency (the Social Security Administration, or SSA) would arrive on the scene in the 1930s to provide information about working-age people from this era.

Given that, you should secure as many Social Security-related resources as you can for each qualifying relative. Created by the SSA, these documents can help you break down break walls and solve genealogy mysteries. Here are the Social Security records you’re looking for—and a little context to help you fit them into your family’s timeline.

A History of Social Security

The Social Security Act was signed into law in 1935, during the Great Depression. Its purpose was to fund unemployment and old-age benefits by taxing workers’ wages. Anyone under the age of 65 as of 1 January 1937—including immigrants—could apply for a Social Security number, which tracked employee contributions and benefits eligibility. The SSA assigned numbers according to a system that factored in location and year; see Stephen P. Morse’s One-Step tool for how to decode them.

Tax collection began in 1937, and benefit payments started in 1940. By this time, spouses and minor children had been added to the plan. Over the next few decades, Social Security expanded dramatically, culminating with the launch of Medicare in the mid-1960s. Many people over age 65 who hadn’t already signed up scrambled to do so.

So which of your relatives may have a Social Security paper trail? Any US resident in 1937 or later, especially those who worked a tax-paying job or were married to someone who did. Look for applicable people in the 1940 census, if they’re listed.

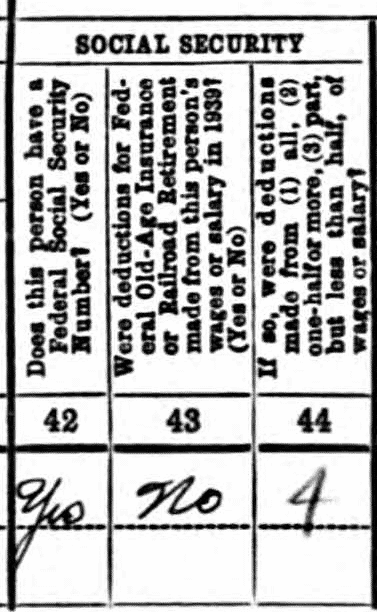

Better yet, if, to the left of your relative’s entry in the 1940 census, it says “SUPPL QUEST” (supplemental questions), look to the bottom of the page. Questions 42 through 44 were about their Social Security participation; my great-grandfather John Felix’s responses are indicated below.

Social Security Applications (SS-5s)

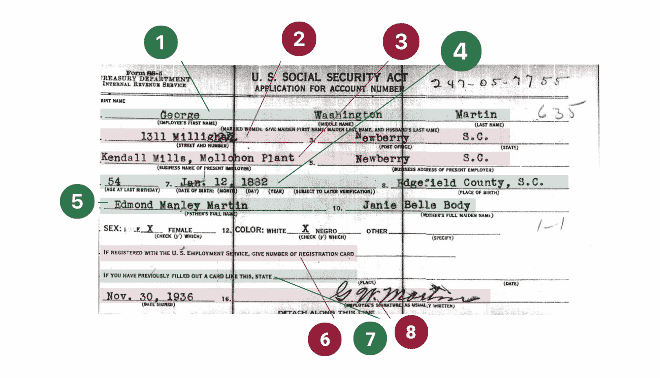

Those applying for Social Security had to fill out an SS-5 form. Though the application forms varied throughout the years, they typically required:

- Full name at birth, including a woman’s maiden name

- Mailing address and age at last birthday

- Date and place of birth

- Parents’ full names, including mother’s maiden name

- Race/color

- Current employer’s name and address

- Dated signature

Through the SSA website, you can order copies of SS-5 applications for deceased people or, with their written permission, for the living.

Whether your request for a deceased person’s SS-5 is successful depends on two factors: how long ago the applicant was born, and whether the SSA has sufficient evidence of his or her death. The SSA’s instructions are a little confusing on the subject beyond that. As written, they indicate that you’ll receive information if the applicant was born more than 120 years ago, or if the applicant was born more than 100 years ago and you provide proof of death (such as a death certificate, obituary, coroner’s report or statement by a funeral director or attending physician). Certain details—like the names of parents or employers—might be redacted if the SSA can’t confirm they’re also deceased.

Use the order-by-mail option if you need to submit any evidence. Provide all information requested—including the Social Security number, if you have it—to be sure you get the right record. Copies of SS-5s aren’t cheap, so confirm the applicant’s participation in Social Security before you request them by consulting other records mentioned in this article.

If your request seems unjustly redacted or denied, appeal it. Provide copies of tombstone images, parents’ census entries showing ages, and other evidence to strengthen your case.

In addition to the SS-5 form, you’ll also see an option for something called a Numident record. Though the Numident is cheaper to order, it contains less information than the full SS-5 and thus isn’t as useful.

Besides, the Numident extracts you want may be freely available at the National Archives’ Access to Archival Databases (AAD) (Genealogy > Civilians > Numerical Identification Files). There you’ll find multiple searchable indexes to SS-5s, grouped alphabetically by surname. Not all SS-5s are indexed here, such as many completed prior to 1973, or those for births after 1908. Files for living people are excluded. The SS-5 Numident extracts may include a person’s name(s), sex, race, birth data, parents’ names, alien registration number and more.

Additionally, the Social Security Applications and Claims Index, available on subscription websites Ancestry.com and MyHeritage, provides information extracted from SS-5s for millions of people, such as full names, race, birth dates and places, and parents’ full names. This index is much easier to search than the AAD databases, but may not include all details in the free Numident file (and vice versa). Search both, if you can.

Social Security Claim Files

Over the course of a lifetime, Social Security participants accumulated claim files with additional documentation. These often included copies of (or transcribed evidence from) birth or death records, infant baptismal records, family Bible entries, delayed birth records, passports, marriage records, military records or a spouse’s SS-5. There might be requests for changes in records with name changes, such as for women who married or divorced. Applications for benefits could be multi-page documents with family, work history and other data.

Unfortunately, claim files aren’t kept permanently. “We ordinarily destroy claim files several years after the final decision on the claim,” states the SSA on its website. “To request a copy of a deceased person’s claim file, please visit your local office. Sometimes we can recall a claim file from our program service center or a Federal Records Center.” Information about living (or possibly living) individuals will be redacted, and fees may vary.

The good news is that some information from claim files survives in indexed form. The AAD has searchable indexes of many (not all) claim files. Claim file data also appears in the aforementioned Ancestry and MyHeritage collections.

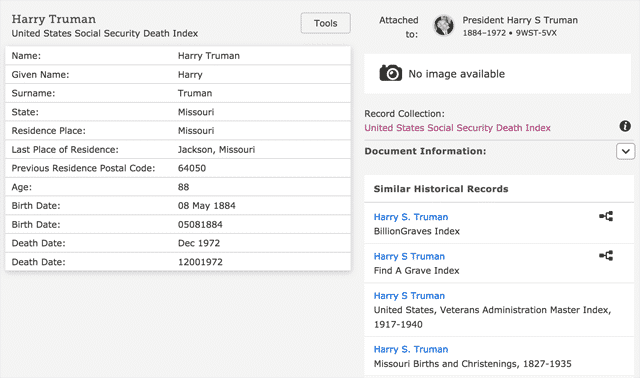

The Social Security Death Index (SSDI)

The Social Security Death Index (SSDI) is a valuable record set that comes from the SSA’s Death Master File, which the SSA uses to track withholdings and survivors’ benefits. The SSDI doesn’t include every person who ever had a Social Security number, generally only including deaths reported to the SSA beginning in 1962 (though a few include deaths prior to that year).

In addition, it might also exclude members of certain professions who had their own security plans and thus didn’t need Social Security numbers (such as railroad workers). And, at time of writing, the SSDI cuts off at 2014.

The SSDI isn’t as detailed as the SS-5. But you should still find the person’s full name, birth date, death date, state where the number was issued, and last known residence (down to the ZIP code level of detail).

You can learn more about the SSDI in the article below.

Tips for Finding Social Security Records

You may be surprised at the patchwork paper trail you find for any given person. Perhaps you’ll find no SS-5, but you discover a claim file extract; the SSA estimates that’s the situation for many records. Conversely, millions of SS-5s and claim file numbers don’t seem to have corresponding death files. While it might be disappointing to not find everything, don’t let one missing record type deter you from looking for others.

Conflicting information can also be a problem. Remember, each type of record may have been created at a different time, under different circumstances, and even by different people. Over a lifetime, a person might report her own birth date differently for a variety of reasons. Some Social Security records could be filled out by others, such as death benefit paperwork by a beneficiary.

Secondhand information and evidence gathered long after the fact are generally less reliable than firsthand information supplied closer in time to an event. Again, you may have to compare lots of different records, including the Social Security records, and consider how likely they are to be right.

Consider the case of Henry Fox of Pueblo, Colo. In his SS-5 application in 1937, he said he was born in 1887. His WWI draft application and the 1940 census agree. But his WWII draft registration states a birth year of 1890, which also appears in the AAD claim file database and the SSDI. And a recently unearthed divorce record for his parents in 1897 says Fox was 8 years old at the time, putting the birth year about 1889 (the same year as his parents’ marriage).

More Records You Can Find

Your search for Social Security-related documents might lead you to additional resources. Among them may be:

Delayed Birth Certificates

Many Social Security participants applied for delayed birth certificates if original government records of their birth weren’t available. Supporting evidence cited in the record could include affidavits by those who personally knew of the birth, copies of family Bible pages, or infant baptismal records.

Ask at state or local vital records offices about the availability of delayed birth records, which may be with court records rather than with other vital records. Learn more about delayed birth certificates.

Railroad Retirement Board Pension Files

Railroad employees were assigned Social Security numbers that start with numbers ranging from 700 to 728. Rail workers drew on separate government pensions—not from Social Security—and their pension files can be packed with family history.

Search for railway employees in the Midwest Genealogy Center’s free index (select the U.S. Railroad Retirement Board collection); Ancestry.com has this index, too.

If you find a relative, learn more about ordering pension files.

Federal Employment Records

During the 1930s and 1940s, the federal government employed workers through the United States Employment Service, the Civilian Conservation Corps, Works Projects Administration (WPA) projects, and other initiatives. A discerning researcher might spot clues to this work in relatives’ SS-5 records.

In 1937, Fox’s SS-5 provided a US Employment Service number, hinting at prior association. On a hunch, I entered the name of Fox’ employer in a database of WPA projects and learned that the contractor built a high school between 1936 and 1939 south of Flagstaff, Ariz., where Fox was living.

Explore more WPA resources, and order civilian employee records before 1951 (including WPA and Civilian Conservation Corps).

A version of this article appeared in the January/February 2021 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated September 2020.