Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

As the SS Veendam entered New York Harbor on the morning of Aug. 30, 1892, Franz Schnell waited breathlessly in steerage with his wife and nine children. Ten days before, the family had boarded in Rotterdam, Holland, bidding farewell to their native Russia forever. Now, finally, they were passing through the gate to their future: America!

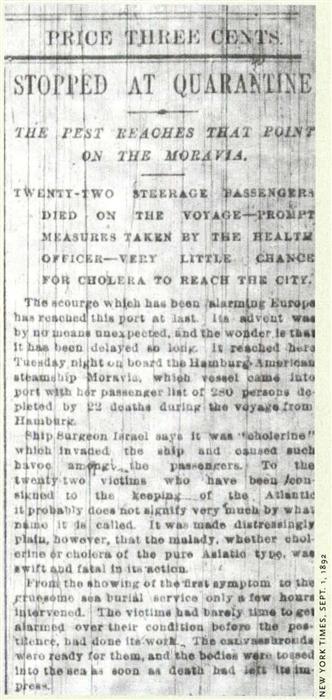

But as soon as the cabin-class passengers stepped onto the pier in lower Manhattan, the Veendam veered away, steamed into one of the detention docks of Staten Island and raised a yellow flag. Cholera had broken out in Russia and spread to other ports. Just the day before, 22 steerage passengers from Bremen had arrived in New York City dead. The eager Schnell family would have to wait — the Veendam was in quarantine.

I learned about the Schnells’ 1892 plight from the New York Times. Detailed articles describe the quarantine process they endured. Theirs was not the only arriving steamship, and the steerage passengers were stuck waiting their turn aboard the Veendam. Finally, on Sept. 1, the Schnells and their fellow travelers were transported to the Quarantine Hospital on Hoffman Island, just outside the Verrazano Narrows. There, they were required to strip and bathe, while their clothing and baggage were sent through a disinfecting steam shower. Then, returned to the Veendam, they waited again: Would the cholera show itself or not?

Of course, the story of the Schnells is only one among millions. Your own immigrant ancestors have their stories, too. What was their vessel’s original port of embarkation? When did they sail? How long did the voyage last? Were the seas tranquil or turbulent? How was the weather? Was there anything noteworthy about the crossing — illness on board, delays, extraordinary speed? Answers to questions such as these can bring your immigrant ancestors’ stories to life — and may even help unpuzzle your pedigree chart.

Like the Schnells’ saga, vivid details about your ancestors’ immigration experiences can be found in the newspapers of their ports of entry. Port-city newspapers in the 19th and early 20th centuries usually had a regular feature titled Harbor News, Marine Intelligence or Port Items, which reported on ships arrived, expected and departed. While the content varied from port to port and from one era to another, such columns generally showed: for every ship — the name, type, registry, tonnage and captain’s name; for departing vessels — the port of destination; for arriving vessels — the port of origin, intermediate ports of call, names of cabin passengers (first and second class), number of passengers traveling in steerage (third class), names of firms receiving merchandise, and the sea and weather conditions of the voyage. Often, when something unusual was noted — in the case of the Veendam, the suspicion of cholera and detention in quarantine — a lengthier article in a separate column provided fuller details.

Before you can access the right newspaper, however, you must learn the name of your ancestor’s ship, as well as its date and port of entry. I knew before I turned to the New York Times that the Schnell family landed in New York on the Veendam in early September 1892. This information is found in passenger arrival records.

You can find US passenger arrival records dating from 1820 through the 1950s on microfilm at the National Archives and its 14 regional archives, the Family History Library and its thousands of Family History Centers worldwide, and many large libraries across the country. Portions of this enormous body of federal records have been published in multivolume sets you can consult at your local library. Other portions have been transcribed on CD-ROMs or digitized and uploaded to the Internet — most notably, the passenger arrival records for the Port of New York, 1892 to 1924.

A variety of alphabetical passenger-name indexes, finding aids and search engines can help you locate one passenger among the millions enumerated on ship manifests for the different US ports.

To use these, you need to know your ancestor’s full original name, approximate age at arrival and approximate year of arrival. Any additional facts about your ancestor’s migration — he traveled with his wife and two children, for instance, or she landed in Mobile, Ala. — will help you identify him or her when other passengers with the same name and about the same age arrived at the same time. For descriptions of available passenger arrival records, visit the National Archives website.

Once you’ve learned the name of your ancestor’s ship and its port and date of entry, you can get the story from the newspaper. Accessing the newspaper you need is easy once you’ve located the passenger arrival record. Newspapers of all five major ports — Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore and New Orleans — and most minor ports — Providence, RI; Galveston, Texas and San Francisco, to name just three — are readily available on microfilm. For more on accessing old newspapers throughout the United States, visit the US Newspaper Program. The Source: A Guidebook of American Genealogy (Ancestry) also contains a chapter listing state-by-state resources for locating newspapers.

Now that you know how to do the research, here’s a look at seven ways maritime reports in newspapers can help you discover fascinating details about the most momentous voyages your ancestors ever made.

1. Discover what your ancestors endured at sea

Crossing the Atlantic by sail was a rigorous undertaking fraught with hazard. Did your ancestors endure turbulent seas and storms? Did they suffer through days of seasickness?

I knew from my ancestor George F. Ring’s naturalization record that he came to America from Lorraine, France, in 1853, at the age of 19. Using the microfilmed passenger arrival records, I found his name on the list of the South America, which sailed into New York Harbor May 21, 1853. Next, I consulted the New York Daily Times for that date to learn what his crossing had been like. The paper’s Marine Intelligence column reported that the South America “experienced heavy weather. Carried away foremast. Had 4 deaths.”

The South America‘s passenger list records no deaths, so I assume the “4 deaths” were members of the crew, perhaps perched atop the ship’s front mast when it toppled into the sea. The 445 passengers, including the adventuresome young Ring, would have been confined below deck during the turbulence. How thankful they must have been when they finally stepped onto the pier, alive, in Manhattan.

2. Prove (or disprove) family stories

In many families, stories about immigrant ancestors are passed on orally from generation to generation. Over years of retelling, the facts become confused or exaggerated, and it’s hard to know what’s truth and what’s fancy. The port’s newspaper may resolve your doubts.

As a boy, I was told that my great-grandfather Ignazio Colletta came to America in the late 19th century and worked for a railroad company, laying track out West. After several years, he supposedly returned to his wife and children in Sicily. The story was plausible, because this practice was commonplace. Agents of American railroad companies would round up laborers in European villages and ship them off in groups. At the port of entry, another railroad official would meet the immigrants and get them to their final destination. The laborers lived in work camps, sending their salaries overseas to support loved ones, then eventually going home. But it wasn’t until I found Ignazio Colletta’s arrival record — and read the newspaper report of his ship’s crossing — that I confidently could believe the story I’d long been told.

His arrival record shows that he traveled on the SS Trinacria, entering the country at New Orleans on June 9, 1890. Ten other men, all from the same Sicilian village, are listed with my great-grandfather. This obviously was one of those groups of paesani traveling together to employment in America.

The Marine News column of The Daily Picayune, June 9,1890, recorded the arrival of the Trinacria, and an article the following day, “Nautical Notes: Immigrants from Italy,” supplied the particulars. It was a “British steamship … 1466 tons net, Captain G. Mitchell, from Leghorn April 27, via Messina May 5, Palermo May 14, and Gibraltar May 18. … She reports having had fine weather to Gibraltar, thence fresh southwest and west winds, with head seas to Abaco, followed by fine weather to the passes, crossing the bar at noon on the 8th inst., anchored at midnight, and arrived at the Northeastern Railroad at 1 a.m. yesterday.” The Trinacria carried “fruit and 450 Italian immigrants,” among whom were my great-grandfather and his buddies, commuting to work, you might say.

3. Uncover how they traveled

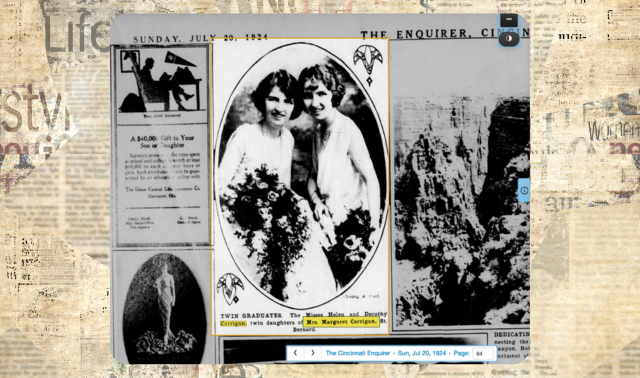

Not all immigrants came in steerage; those who could afford to traveled in cabins. Port newspapers typically printed a list of all arriving cabin-class passengers, but that list rarely exceeded a dozen names. Nevertheless, you never know about your ancestors until you check: Were they among the lucky few?

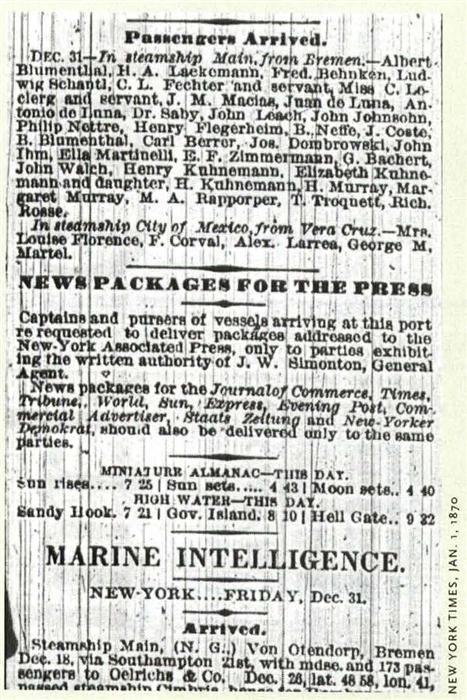

Sometimes, it’s the researcher who gets lucky. Joseph Dombrowski, a young man from Russian Poland, landed in New York Dec. 31, 1869, on the SS Main. The ship’s manifest clearly lists Dombrowski among the steerage passengers. Remarkably, though, in a Times column titled Passengers Arrived, “Jos. Dombrowski” appears along with 30 other names. The Times must have named not only the vessel’s first- and second-class passengers, but also a random selection of steerage passengers, as well.

Dombrowski was a poor priest on his way to teach in a Catholic boys’ school in Detroit, yet his name appeared in the New York Times. Not a bad welcome from his new country, though Father Dombrowski probably never saw it.

4. Find a date of departure

Although US passenger arrival records always note the ship’s date of arrival, prior to 1893, they rarely contain the date of embarkation from the foreign port. How long did it take your ancestors to cross the Atlantic? Check the newspaper!

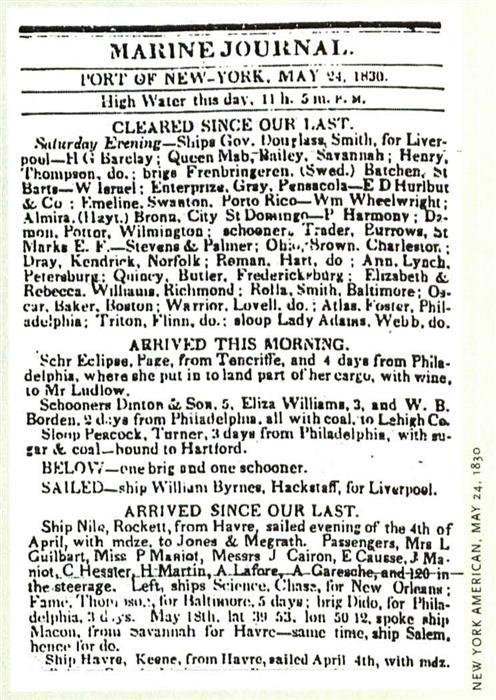

When the Nile sailed into New York May 24, 1830, from Le Havre, France, the 120 passengers in its steerage included Nicholas Miller, age 51, and his family of bricklayers en route from their village in Lorraine, where there was no work, to Buffalo, NY, where there was plenty. The Marine Journal of the New York American recorded that the Nile “sailed evening of the 4th of April.” A simple calculation — April 4 to May 24 — reveals that the Millers were at sea for seven weeks and one day.

Learning your ancestor’s ship’s precise date of departure also allows you to investigate the conditions in the port of embarkation when your ancestor was there. Such detail personalizes the migration story. For example, in late March and early April of 1830, Le Havre was just coming out of one of Europe’s most severe winters. Snowfall had been unusually heavy, and ice in the harbor was thick. People poured into the city to sail to America (most emigrants traveled in spring), spending their savings on food and lodging, while they waited anxiously for the ice to break. Temperatures remained below freezing, though, and the boarding houses and inns filled to capacity, leaving some emigrants stranded in the snowy streets.

The Miller clan must have grown desperate. Surely they rejoiced when the sails of the Nile were at long last unfurled.

5. Learn about fellow travelers on board

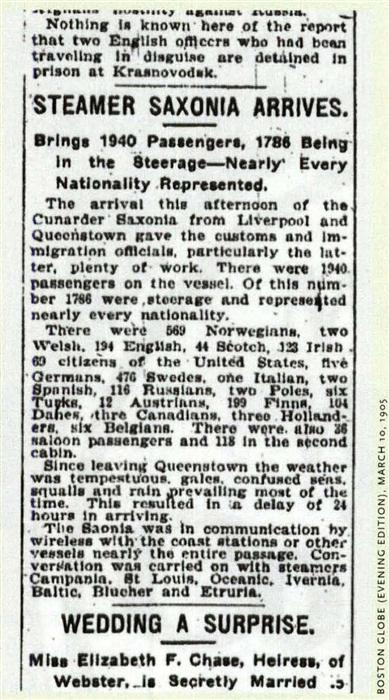

By the turn of the 20th century, steamships were many times larger and swifter than earlier sailing vessels. Moreover, steerage conditions were much improved, and the experience of living with hundreds of people of disparate cultures may well have been a fascinating adventure for your ancestors. For example, according to the evening Boston Globe of March 10, 1905, immigration officials had their hands full when the SS Saxonia arrived with the most steerage passengers Boston had seen in a long time. Swedish emigrants Ole Hagstrom, his wife, Ida, and their children, Naomi, Olof and Nellie, were only three of 1,786 third-class passengers on board the gigantic liner, which also carried 115 passengers in second class and 36 in first class.

The Globe printed a breakdown of the record-breaking horde: “569 Norwegians, two Welsh, 194 English, 44 Scotch, 123 Irish, 69 citizens of the United States, five Germans, 476 Swedes, one Italian, two Spanish, 116 Russians, two Poles, six Turks, 12 Austrians, 199 Finns, 104 Danes, three Canadians, three Hollanders, six Belgians.” After spending seven days on the Atlantic in this company, the Hagstroms must have gotten a taste of what their new, ethnically diverse country would be like.

6. Find the correct date of arrival

You may discover a discrepancy of a day or two in the arrival date of your ancestor’s ship. The dates appear in three different sources: the register kept by the harbor master, the passenger list sworn to and signed by the captain, and the newspaper. If a ship pulled in late at night, the register shows its arrival at that hour. But not until the next morning would the passengers be able to disembark and pass through immigrant processing. By the time the captain signed and dated the manifest, certifying that it was accurate, it was actually the day after his ship had entered the harbor.

At peak times of immigration in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when steamships held up to 2,000 passengers, entire shiploads of steerage passengers often had to wait to be taken through processing at the immigrant receiving station. The passenger list of the SS Aurania, which steamed into New York from Liverpool, England, via Queenstown, Ireland, bears the handwritten date “Feb. 21, 1893.” On board were Patrick Sheehan, his wife and six of their eight children, fleeing the overpopulation and poverty of County Kerry. Yet the New York Times that day reported that the Aurania “arrived at the Bar … with mdse. and passengers … at 2:45 P M” on the previous day, Feb. 20. The Times listed five other passenger liners landing on Feb. 20, so it’s likely that the Sheehans weren’t processed through Ellis Island until the following day, Feb. 21 — the date penned on the ship’s manifest.

7. Read reports on shipboard accidents or processing problems

Your ancestors’ trans-Atlantic adventures may have included a shipboard accident or processing problem that was reported in the newspaper. Consider the 1907 saga of the SS Arconia, an old, slow steamship with a reputation for rolling heavily. Built in 1896 as the Dunolly Castle, it was sold in 1905 and renamed the Juliette, then sold again in 1907 to the Russian-American Line and named Arconia. On board the Arconia‘s maiden trans-Atlantic voyage was Abraham Laskin, a 19-year-old Jew escaping the oppressive Russian life. He was probably grateful for the cheap transportation to America; however, the Arconia‘s steerage accommodations reflected the appalling conditions of an earlier age, and it took 15 days to cross a distance traveled by newer steamships in six or seven. Worse, a brutal accident marred Laskin’s voyage. “Scalded on Shipboard,” a New York Times article that ran on June 10, 1907, revealed that six of Laskin’s fellow steerage passengers were seriously burned by steam one night when they tried to use the Arconia‘s bathroom. The article reflected the disdain officials felt for these “huddled masses.”

Laskin wasn’t among the injured, but a second piece on the same page of the Times described another incident that probably did affect the young Russian. One of the ferries used to transport steerage passengers from the docking pier at the foot of Manhattan to Ellis Island broke down. Even if Laskin wasn’t on board that particular ferry, he would have been inconvenienced by the delay the mishap caused in immigrant processing. The Arconia entered New York Harbor on June 9, but Laskin didn’t go through Ellis Island until June 10. Here’s yet another possible explanation for a discrepancy in arrival date — a broken-down ferry.

George F. Ring, Ignazio Colletta, Father Dombrowski, the Miller clan, the families of Ole Hagstrom and Patrick Sheehan, Abraham Laskin — these seven immigration stories become more than mere dates and names through information found in the ports of entry’s newspapers.

What did the New York Times reveal about the plight of Franz Schnell, his wife and nine children, and their fellow passengers quarantined on board the Veendam? No cholera was discovered on board. On Sept. 3, 1892, the yellow flag was lowered, the Veendam steamed into a pier of lower Manhattan, and the Schnell family proceeded through Ellis Island. At long last the gate was open, and they could begin life in their new land.

The Schnells’ story has a happy ending. Don’t stop investigating your own immigrant ancestors when you find their passenger records — use them as springboards to explore their experiences, happy or tragic, stormy or smooth. You can read all about them, in the newspaper.

Online Historical Newspaper Resources

- US Newspaper Program: Preservation and cataloging projects in all 50 states.

- Library of Congress: Newspaper Indexes, Archives, Morgues: Links to dozens of period newspapers.

- American Newspaper Repository: Nonprofit group dedicated to saving newspapers in their original form.

- Newspaper Abstracts: Searchable archive of newspapers published before 1923.

- Immigration History Research Center: Extensive collection of ethnic newspapers.

- The Olden Times: Scanned collection of 18th-, 19th- and early 20th-century US newspapers.

- National Library of Canada: More than 200,000 reels of newspapers on microfilm, which can be requested through interlibrary loan.

- Newspapers.com: subscription site of old newspapers

- New York Times (1851 to 1999): Major libraries across the country pay a hefty fee for access to this invaluable digital collection from ProQuest Historical Newspapers. Ask your local librarian for details.

A version of this article appeared in the February 2003 issue of Family Tree Magazine.