The United States of America is oft-touted as a nation of immigrants. But arrival to (and citizenship of) the United States varied greatly depending on one’s place of origin, race, political leanings, and marriage. Today, the process generally requires visas, mountains of paperwork, and endless waiting periods.

But that hasn’t always been the case. Immigration laws have become much stricter as time has gone on, and immigrating in the 20th century was much more difficult than in the 18th century. In fact, up until the mid-19th century, few laws restricted US immigration policy. And immigration was generally managed by states or local boards (not the federal government) until the 1880s.

Learning the laws in place at the time of arrival—or any time within our US ancestors’ lifetimes—can help us better navigate the records that may be available, understand why they made certain choices at certain times, and contextualize the lives of our immigrant ancestors.

With more restrictions came more (and richer) records. Here are the key moments in US immigration law, organized by era to aid your research. Throughout, I’ve provided citations for the federal statutes so you can read the legislation yourself.

Note: The article that follows covers laws related to voluntary migration. Laws regarding slavery were substantially different. The slave trade was regulated from its beginning in the 1600s, then officially banned in 1808. (Despite this, the enslaved were still clandestinely brought to the United States through the 1850s.)

1700s and 1800s: Early Laws (or Lack Thereof)

Early in American history, it was more common for individual states to pass their own laws related to immigration. A handful had laws excluding impoverished or diseased individuals, as well as free people of color.

Notable exceptions were the infamous Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 (among them, 1 Stat. 570 and 1 Stat. 577). These federal laws allowed for “aliens” (non-citizens) deemed dangerous to be detained, and male residents over the age of 14 could be deported if they were still subjects of a country with whom the United States was at war. The Alien and Sedition Acts were unpopular and short-lived, with most of them expiring or repealed by 1802.

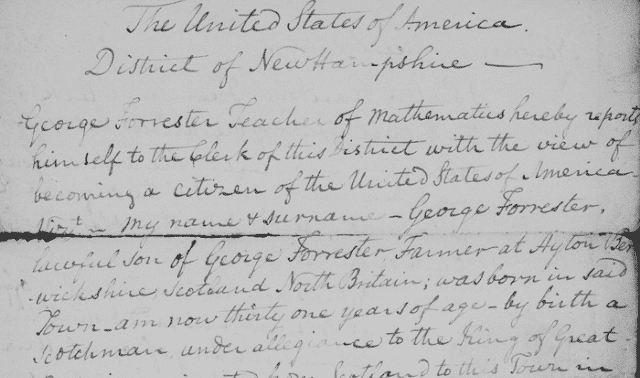

It wasn’t until 1820 that Congress mandated records of arriving individuals in any type of sustained and uniform fashion. And even then, the Steerage Act of 1819 (3 Stat. 488a) was used mainly to regulate the flow of consumer goods and ensure that ships were not overcrowded—not to limit the number of immigrants. This law created customs lists, which genealogists often use to track 19th-century immigrant arrivals.

Decades later in 1864 during the Civil War, Congress passed the first substantive legislation to regulate immigration (13 Stat. 385). The act was meant to replenish the wartime economy’s depleted workforce of able-bodied men, and allowed for employers to pledge new arrivals’ wages against their immigration costs in exchange for one-year labor contracts.

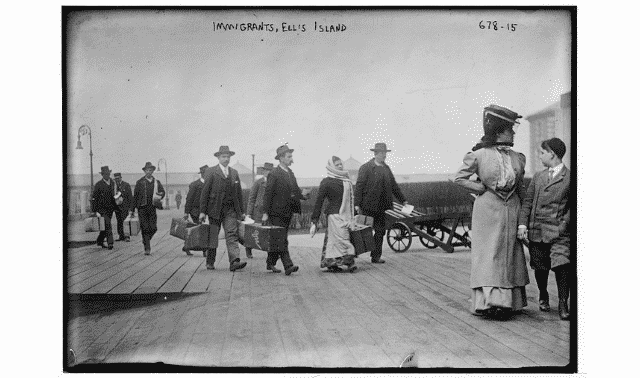

The act also, for the first time, called for a federal Commissioner of Immigration and an immigration office New York City. Partially because of this, New York City became by far the largest port of entry to the United States, especially through the hubs at Castle Garden (1855–1890) and Ellis Island (1892–1924).

Shortly after, the 14th Amendment specified that all individuals born on US soil would be considered US citizens. Additional legislation in 1875 clarified that only white and Black individuals were entitled to naturalization; immigrants from Asian countries were not. This began an era of exclusion that pervaded US immigration and naturalization law for nearly a century.

1870s and 1880s: A Turning Point

Prior to the 1880s, if individuals could afford passage and were physically well enough to survive the journey, they could generally immigrate to the United States. It wasn’t until the latter part of the 19th century that restrictions based on ethnicity, health or class/means were introduced.

The 1876 Supreme Court case Chy Lung v. Freeman specified the power to regulate immigration rested with the federal government, not with individual states. Congress quickly took up the mantel.

1882 proved a turning point for immigration into the United States. The Chinese Exclusion Act (22 Stat. 58) prohibited Chinese individuals from citizenship, and also severely restricted immigration from China for decades to come.

That same year, a new immigration act (22 Stat. 214) introduced the first-ever head tax for every arriving immigrant, and also applied various categories for exclusion of immigrants—including becoming a likely public charge. This act is widely recognized as the first legislation to create an immigration bureaucracy.

Later laws in the 1880s and 1890s denied entry to contract laborers (23 Stat. 322) and fully federalized the immigration process (26 Stat. 1084). The latter, the 1891 Immigration Act, expanded the list of inadmissible immigrants, changed the function of passenger lists from customs to immigration regulation, explicitly made it illegal to aid unauthorized immigrants in coming to the United States, and extended immigration policies to the northern and southern land borders.

An 1893 law (27 Stat. 569) introduced the Boards of Special Inquiry (BSI), in which immigrants who were possibly inadmissible could be questioned. These laws changed the look of passenger lists, and are responsible for the Board of Special Inquiry and Detained Aliens records sometimes addended to ship manifests (especially in New York).

The 20th Century: An Era of Severe Restriction

The list of inadmissible aliens continued to grow in the new century. Immigration acts in 1903 (32 Stat. 1213), 1907 (34 Stat. 898) and 1917 (39 Stat. 874) excluded anarchists, epileptics, and illiterate adults. These laws also increased the government’s deportation authority, increased the head tax, and added several columns to ship manifests.

The 1917 law also barred immigrants from the “Asiatic Barred Zone,” essentially ceasing immigration from most parts of Asia, the South Pacific and the Arabian Peninsula. Combined with the Chinese Exclusion Act (which had been indefinitely extended) and the Gentleman’s Agreement of 1907 (which ceased Japanese immigration), immigration from Asia was virtually at a standstill.

The 1920s brought the severest immigration restrictions the United States had ever seen. Strict quotas were placed on immigration. Under a 1921 law (42 Stat. 5), annual immigration from specific countries was capped at 3% of the number of immigrants from that country living within the United States as of the 1910 census. A 1924 law (43 State. 153) restricted that even further: 2% of immigrants as of the 1890 census.

These laws were seen by many as a defining point in American immigration legislation, as they were the first time immigration was restricted by numbers and a quota system.

The 1924 law also mandated that aliens obtain visas in advance of travel from a US embassy or consulate abroad. This created the Visa Files series, records now obtainable through the USCIS Genealogy Program. The files include photographs, vital records, and sometimes even testimony or other family records, making them an invaluable resource to 20th-century immigrant researchers.

Despite the strict quotas, immediate relatives of US citizens could essentially bypass the restrictions. They were given preferential or non-quota visas, incentivizing married males to migrate by themselves, then naturalize as quickly as possible to bring over the rest of their families.

Immigration decreased, and the federal government created more departments to enforce the restrictions. This period saw the creation of the U.S. Border Patrol and the consolidation of a few agencies into the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS).

Around the same time, the new Registry system (45 Stat. 1512 and 53 Stat. 1243) allowed immigrants to legalize their status if their arrival was irregular or undocumented. Many individuals who underwent Registry did so in order to naturalize as US citizens; individuals who arrived after 1906 needed to prove they had entered the country lawfully.

As World War II began in Europe, the United States required alien registration by all non-citizens ages 14 and over. More than 5.6 million individuals registered under the law (54 Stat. 670), generating a valuable record set—the AR-2 series—even for immigrants who had long lived in the United States but had never naturalized. (In order to be granted a visa to immigrate, one also needed to complete an alien registration form.)

The alien registration program also directly led to the creation of the A-Files series, individual immigrant files organized by a unique identification number. (USCIS, INS’ successor, still uses A-files to this day.) A-Files are a unique and rich source for any immigrant who has arrived to the United States since April 1944, and/or who registered under the Alien Registration Act of 1940 and had further interaction with the INS.

The tide began to turn during and after World War II. The Chinese Exclusion Act was finally repealed in 1943 (57 Stat. 600), allowing limited immigration from China as well as citizenship for Chinese individuals currently in the United States. Limited immigrants from India and the newly independent Philippines were allowed starting in 1946 (60 Stat. 416), as well as the naturalization of Indians currently in the United States.

Further immigration laws were passed after the war to account for the redrawing of national boundaries and the displacement of many Europeans. The 1946 War Brides Act (59 Stat. 659) provided for the expedited admission of alien wives and children of members of the U.S. Armed Forces. And the Displaced Persons Act of 1948 (62 Stat. 1009) and Refugee Relief Act of 1953 (67 Stat. 400) allowed for the resettlement of about 400,000 displaced persons and refugees in the United States.

As part of an anti-Communist push, the 1950 Internal Security Act (64 Stat. 987) strengthened exclusion, detention and deportation laws, and mandated that certain aliens register their address with the INS Commissioner.

A Note on Naturalization

It’s hard to divorce the discussion of naturalization from the discussion of immigration, though US citizenship has never been a requirement for immigrants. Congress enacted the first naturalization law in 1790.

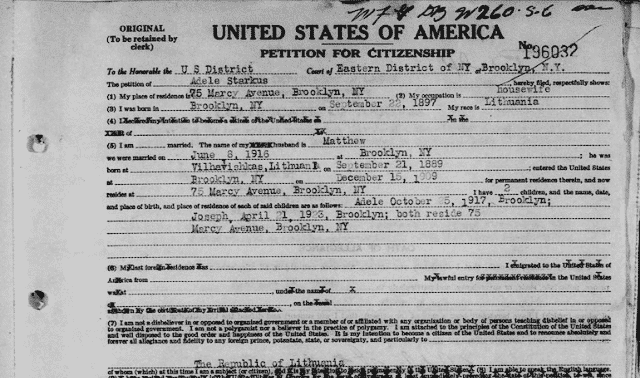

Generally, naturalization was allowed by free white individuals (and, from 1870, free Black individuals) after a certain amount of time living in the United States and upon completion of a declaration of intention and petition for naturalization. People of Asian descent were denied the right to become citizens until the INA of 1952 abolished remaining racial barriers to naturalization.

Naturalization was federalized and standardized in 1906; prior to that time, one could apply for naturalization in many different courts; there was no standard format, fee or location. This law centralized immigration records, required a certain level of fluency in English, and required proof of lawful entry.

Laws differed somewhat for married women. Beginning with an 1855 law, women who married US citizens (or whose alien husbands naturalized) were to also be considered US citizens. Likewise, beginning in 1907, native-born women lost their citizenship upon marrying alien men—even retroactively. The Cable Act of 1922 separated the citizenship of a woman from that of her husband, though women who married Asian men were not included in this law until a 1931 amendment.

1950s to Today: The INA and Beyond

The most important and comprehensive immigration legislation came in the form of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (INA; 66 Stat. 163), which codified many of the previous naturalization and immigration laws into one. It eliminated racial restrictions in immigration and naturalization statutes for the first time in US history, and (despite hundreds of amendments) still forms the basis of immigration law to this day.

The INA of 1965 (79 Stat. 911) continued to expand the list of individuals able to immigrate, abolishing the quota system once and for all and creating a seven-category preference system for immigrants. Many contend this act allowed the demographic mix of America to change dramatically, as Asian, African and Middle Eastern immigrants were allowed in large numbers in a way they hadn’t been before. This directly led to the multicultural and diverse nation we know today.

It’s hard to keep track of all of the immigration laws since the 1700s. But it’s important to build a foundation of the regulations therein. These laws can help us theorize why an ancestor immigrated at one time over another—or why half the family never came at all. They tell us about times of restriction, of opportunity, of hardship. And through it all, we can see the courage of our immigrant ancestors.

Timeline of Important Dates

A version of this article appeared in the Sept/Oct 2023 issue of Family Tree Magazine.