Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

The Homestead Act of 1862 drew people out west with the promise of free land. Of course, the government required significant paperwork to prove eligibility. Fortunately for modern genealogists, the paperwork our ancestors went through provides us with a way to learn about them.

History of Homesteading

The offer of free land enticed many to migrate westward. The Homestead Act was passed in 1862 and took effect on New Year’s Day in 1863. The first homesteader applied that very same day and settled in Nebraska territory.

Those who had taken up arms against the U.S., or Confederate veterans, were not allowed to apply; this ensured that slavery would not be spread to the West. On the other hand, Union veterans, or anyone else who served in the U.S. military, could count their military service toward the five-year residency requirement. In 1866, Confederates were allowed to homestead in former Confederate states.

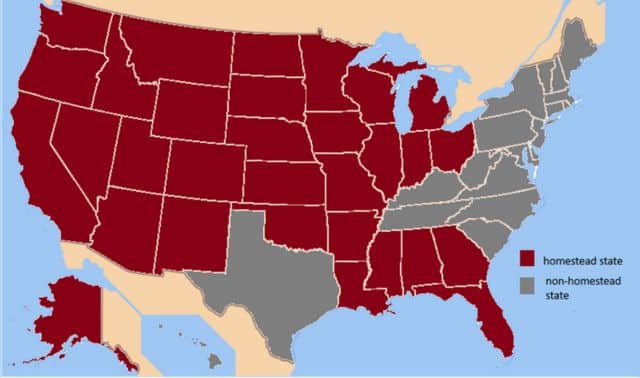

30 of the 50 states offered homestead land. The map below shows the states in red that offered homesteads, and the ones in gray did not. The states that did not provide homesteads included the original 13 colonies, Texas, and Hawaii.

The Homestead Act was open to U.S. citizens old enough to vote. Since the law did not specifically exclude them, women and African Americans could also obtain homestead land. This allowed women to own land in their own names (rather than a husband’s or father’s) and provided opportunities for formerly enslaved persons. As for immigrants, they did not have to be citizens when they started the process, but they had to be naturalized by the time they proved their claim.

The Homesteading Process

Homesteaders would apply at the land office and pay the application fee (usually $10). They were then required to live on the land for five years and improve it by growing crops or raising livestock. After five years, the homesteader could prove their claim and pay the last fee (usually $8). Proving the claim involved the most paperwork and required witnesses. Once the claim was proven, the land office would issue a patent to the homesteader. Alternatively, a homesteader could purchase their land for $1.25 per acre after they’d lived there at least six months; this was known as commuting.

The homestead process was easier said than done. Only 40% of those who applied completed the process. Extreme weather, fires, severe droughts, and pests easily ruined crops. Due to the lack of trees, many had to build their houses out of sod. Settlers also had to supply their own farming tools. Many gave up their claims (which were often taken by others) or declared bankruptcy. Some went back East. Some could not afford to go back East, so they stayed and toughed it out. For those who completed the homestead, some stayed for generations, while others sold the land and moved on.

If a claimant did not apply for the patent seven years after starting the homestead, their claim would be cancelled. Sometimes the claimant died before it was complete, so his widow or heirs would complete it for him. There was also fraud and abuse in the system due to corporations looking for loopholes.

![]() Survey System

Survey System

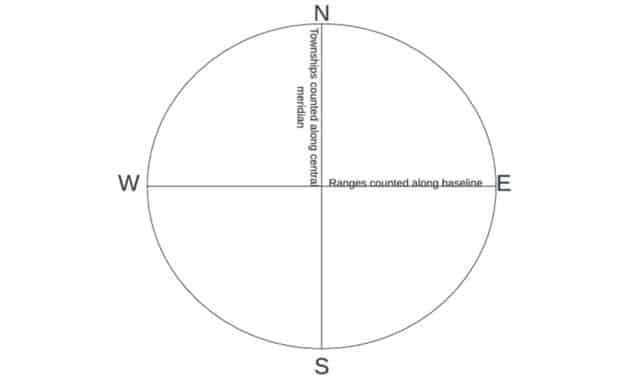

Each homestead equaled 160 acres, surveyed via the Public Land Survey System. This system was based on gridding the land, which started at a central meridian point and counted out miles in every direction. The Township line was North to South, and the Range line was East to West. Each range or township was six miles long.

Each range and township square was divided into 36 sections, each one square mile. The sections were numbered as shown on the chart below.

| 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 18 | 17 | 16 | 15 | 14 | 13 |

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 30 | 29 | 28 | 27 | 26 | 25 |

| 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 |

Each section was then divided into quarters, as shown on the next chart. Each quarter section was 160 acres.

| Northwest quarter | Northeast quarter |

| Southwest quarter | Southeast quarter |

The township and range numbers, section number, and the quarter entailed the legal land description of any given plot. For example, Christian Murri’s neighbor’s legal land descriptions were listed in his homestead papers. One neighbor lived on the Northeast Quarter of Section 21 in Township 3 South Range 4 East. This was abbreviated as NE ¼ Sec 21 Tp 3S R 4E. This means his plot of land was three miles south and four miles east of the central meridian. The charts above can help identify the Northeast Quarter of Section 21.

How the Homestead Act Changed Over the Years

The Homestead Act has evolved over the years. For example, the Southern Homestead Act of 1866 encouraged African Americans to obtain homesteads. A few years later, the Timber Culture Act of 1873 emerged, which had no residency requirement and asked the claimant to plant trees.

This evolution continued into the 1900s. A 1904 amendment allowed for 640-acre homesteads in western Nebraska while one in 1909 increased the homestead size to 320 acres in marginal areas. An act in 1916 granted 640 acres for ranching purposes; another shortened the residency from five years to three.

The Homestead Act ended in 1967 in all places except Alaska. In Alaska, it continued until 1986. The last homestead was completed in 1988.

Women Homesteaders

As mentioned above, the homestead law did not specify that claimants had to be male, so women could file for homesteads. This provided an opportunity for single or widowed women to own land. Sometimes a woman married or remarried before completing the homesteading process, so she had to provide her marriage date when proving her claim. Some women took over homesteads that their husbands started. This included widows whose husbands died during the process, women whose husbands abandoned them, and women married to men incapable of running a household. A woman could file for a homestead if she was the head of household. The advent of the railroad brought more female homesteaders.

Most female homesteaders formed cooperative relationships with each other, family, and their neighbors. Often, they sought local help to build their homes, plow their land, and harvest their crops. They would often share the profits to pay for help. Male homesteaders also needed skills women had, so they’d hire their female neighbors for help with laundry, cleaning, cooking, and selling homemade or homegrown items. Many women worked as schoolteachers to support their homesteads.

Immigration and Homesteading

Homesteading afforded new opportunities for immigrants, such as Christian Murri. In some places, the cost to file the homesteading paperwork was less than that of renting a single acre. In most of Europe, owning that much land was also unheard of. Thus, obtaining a homestead appealed to farmers who didn’t own land. In European countries that practiced primogeniture (where only the oldest son inherits), the younger sons who wouldn’t inherit were drawn by the prospect of owning land.

The Homestead Act increased immigration, which had been stagnant during the Civil War. It attracted people from Palestine, Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, Germany, Egypt, England, Sweden, Canada, Spain, France, Russia, and Italy. There were enough immigrant homesteaders that the 1870 census showed higher percentages of foreign-born individuals in the Great Plains than on the East Coast.

Impact of homesteading

The intended purpose of encouraging settlement in the West was successful. Some of the Midwest states saw massive population growth. Not only was there the pull of land in the West, but there was also overpopulation in the East. Cities in the West were built to process crops.

The Homestead Act lasted for 123 years. Around 270 million acres of land were homesteaded. In some places, entire communities were formed around homesteading, often based on ethnic or religious groups. With roughly 4 million claims filed, it is estimated that there are currently 93 million living descendants of homesteaders.

The Homestead Act was not so kind to Native Americans, as the U.S. government confiscated land from them to give to settlers. The Dawes Act was an attempt to rectify this wrong. It was passed in 1887 and allowed the federal government to divide tribal lands. Native Americans who accepted this division were allowed to become U.S. citizens.

The railroad also impacted homesteading, making it easier for homesteaders to travel West to claim land. Conversely, it would have also made returns to the East easier. The same year the Homestead Act was passed, Congress also chartered the Central Pacific and Union Pacific Railroad companies. One company built a railroad from the East and the other from the West. The two companies met in 1869, connecting the transcontinental railroad. After this, the railroad was the life and death of towns.

Finding Homesteading Records

Clues for Homesteading

How do you know if your ancestor was a homesteader? Clues can be found in many types of records. Census records might show migration to a federal land state after 1862. This can be pinpointed by noting the birthplaces of family members. The head of household would be a farmer who owned property. The agricultural schedules of the 1870 and 1880 censuses will show how much land a farmer owned, which would be 160 acres for a homesteader (or 320 or 640 for later homesteaders). Deed books would list the grantor as the United States. Tax lists may also give clues to how much land was owned. Probate records described the land being passed down to heirs.

Further clues may be found in looking up the historical context in places such as county histories, historical monographs, and county historical societies.

What is in the Records?

The homestead records give the legal land description of the land homesteaded, which allows for finding it on a map. If the neighbors’ land descriptions are known, they can be mapped together to visualize where everyone in the community lived.

An immigrant who had begun the naturalization process could apply for a homestead. Immigrant homesteaders had to naturalize before they could prove their claim and provide their naturalization papers to the land office. Therefore, an immigrant’s homesteading papers often include the naturalization papers. This was the case for Christian Murri.

It was previously mentioned that some homesteaders died during the homestead process, and their widows would take over. In such a case, the homesteader’s death date would be included in the homestead papers. It was also mentioned that some female homesteaders would marry or remarry during the process; here, the homestead papers would include the marriage date.

It was mentioned above that proving the claim required witnesses and much paperwork. Along with what was just discussed, the homesteader had to answer a questionnaire about their property, how long they lived there, their family, the house they built, the crops they grew, and the value of the land. Witnesses had to sign affidavits regarding the claimant.

The involvement of witnesses makes homestead research useful for identifying an ancestor’s neighbors. Neighbors often witnessed each other’s homesteads. Witnesses were supposed to be disinterested parties, meaning not related. But this wasn’t always enforced.

In their affidavits, witnesses had to testify about how long the claimant had lived on his land, how often they saw the claimant on his (or her) land, how long they knew the claimant, and how close they lived to the claimant.

All the paperwork for proving the claim is only available for completed homesteads, which, as discussed above, was only 40% of them. The incomplete homesteads are harder to identify. One place to find abandoned homesteads is in the state’s tract books. These give the legal land description and the names of the first owners of the land, and often indicate whether the land was purchased or homesteaded.

Where Can Records be Found?

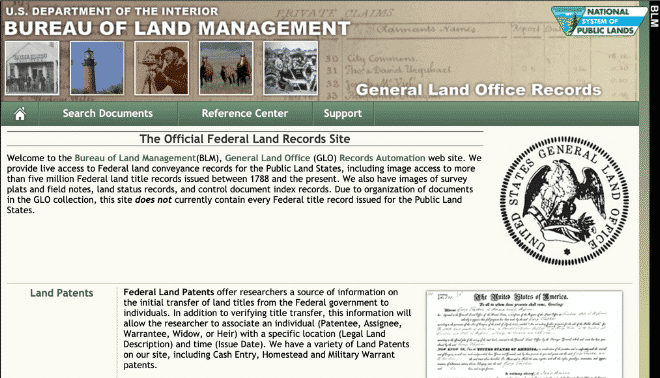

The National Archives (NARA) holds many homesteading records, which Ancestry and Fold3 are digitizing. If your ancestor’s records are not found online, they may be waiting to be digitized. NARA’s article explains how to obtain homesteading records from them.

Homestead records can also be found at the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the General Land Office (GLO) websites. The BLM only holds patents for those who have completed the process, and its website only has an index. Once the record has been identified, it can be ordered through the National Parks Service.

State land offices may also have homestead records. Each state’s website will vary, and what’s available will depend on the state. Maps were found for Christian Murri on the Utah Land Office website.

Tract books can be found on FamilySearch. Most are digitized but not indexed, so they must be browsed. Each state organized its tract books differently. You will need to determine how your ancestor’s state organized its tract book to browse the collection successfully. Christian Murri’s entry was found in the tract book for Utah.

Case study: Applying Homestead Research

Christian Murri immigrated from Switzerland and homesteaded in Utah during the 1880s. His homestead papers were found on Ancestry. The Ancestry file contained 30 images.

Christian Murri applied for his homestead on 30 October 1882 and proved it on 27 August 1888. His patent was issued on 5 September 1888. His entry was the Northwest Quarter of Section 22 of Township Three South and Range Four East of the Salt Lake Meridian (NW ¼ Sec 22 T 3S R 4E SLM) in Wasatch County, Utah. He paid a $16 fee. Putting this number into an online inflation calculator showed the 2025 equivalent to be $501.65.

Christian Murri and his sons built a house on the property in April 1883 and moved into said house on the 14th of that month. He and the witnesses testified that it was a log house with a board floor and a shingle roof measuring sixteen feet by twenty feet. It had a door and two windows and was habitable year-round. House furnishings included a stove, cooking utensils, dishes, a table, six chairs, three beds, and bedding. He had owned the furniture for ten years. This house was their only home.

The improvements made to the farm included breaking and plowing 17 acres to grow wheat, potatoes, oats, alfalfa, and other vegetables. By the time he proved his claim, Christian had been growing crops for five seasons and had 17 acres in crop. He had built a corral, a stable, a granary, a chicken coop, pig pens, and water ditches on his farm. His farming implements included a plow, two harrows, and a wagon, all of which he’d owned for four years. It is safe to assume he borrowed tools in his first year.

When Christian proved his claim, his house and ditches were each valued at $100 ($3,366.31 in 2025), and everything else he’d built was collectively valued at $200 ($6,732.61 in 2025). This totaled $400, vastly improving from the $16 he paid in 1882.

Christian Murri had to become a citizen before he could prove his claim, so his naturalization papers are included with his homesteading papers. His declaration of intention was filed on 30 October 1883, after he had applied for his homestead. On the homestead application, he swore that he had already declared intention, which the records show otherwise. His certificate of citizenship was issued on November 18, 1887.

Christian Murri did not claim military service. Homesteaders who did had to fill out an affidavit for it, which would give clues about their military service.

Before Christian Murri proved his claim, a notice was repeatedly published in the newspaper to announce his intention to prove his claim. A copy of the newspaper clipping, along with a sworn statement from the newspaper manager, was included in the homestead papers.

The witnesses for Christian Murri’s homestead were Conrad Abegglen/Abbeglen and Ul(e)rich Buhler. They were farmers, like Christian. Both men claimed to have been on Christian’s land once every two or three weeks and often saw the Murri family working on their farm. Each lived about three miles from Christian Murri and indicated that John Kumer lived closer. The witnesses gave the legal land descriptions of their plots and John Kumer’s.

As indicated above, Christian Murri’s entry was found in the Utah tract book on FamilySearch. Utah’s tract book is organized by range and township, so it was necessary to know the legal description of Christian’s land to find him there. If his was unknown, but a neighbor’s was, searching that neighbor would have helped to find him.

Christian Murri’s homestead patent was found on both the BLM GLO website and on the Utah Land Office website. Maps were also found on both websites and compared with Google Maps.

Conclusion: Learning from Homesteaders

Our ancestors who took advantage of the Homestead Act left behind a paper trail for us. From studying their homesteading records, we can learn much about them, including military service and naturalization.