Got a family mystery on your hands? Or just want to learn more about your ancestors? Then deeds are what you need. County recorders, clerks of court, town clerks and other similarly titled officials (depending on the state) have been recording local land transfers in deed books from the county formation up to today. These are among the earliest and the most complete court records you’ll find.

In the foreword to E. Wade Hone’s classic reference Land and Property Research In the United States (Ancestry Publishing), William Dollarhide notes that “In America, land and property records apply to more people than any other written record.” Your ancestors are likely among those people.

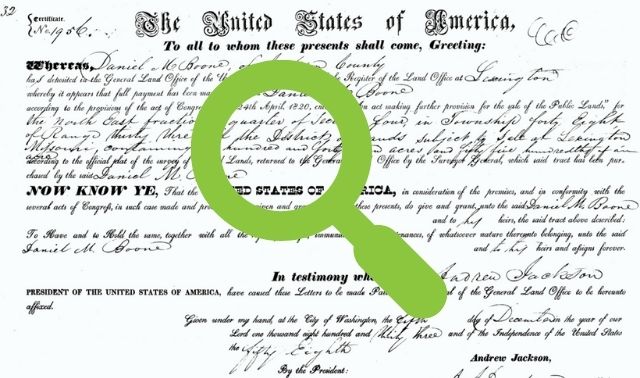

When you dive into deed books, you might find a number of different types of transactions involving your relatives. Someone may have bought or sold land—but remember that original purchases from the federal or state government are generally recorded in land patents, not deeds. When your ancestors inherited property, a deed often would record the transfer of inherited interest. When taxes or debts were owed, your ancestor might have bought land the county seized—or he or she might be the one who lost the land.

These deeds contain a vast amount of genealogical data just waiting to be discovered—some of which might catapult your family research over a brick wall. Here’s how to dig up your ancestors’ deed records and use them to answer 10 common genealogical questions.

How to Find Deeds

Investing in property was as big a deal to our ancestors as it is for us, and they wanted the security of having their ownership recorded at the county courthouse (or in many New England states, the town hall). The deed generally would be signed and then recorded in a deed book, with the new owner keeping the original. If you’re lucky, a court clerk or a modern genealogist created an index to the names recorded in local deed books.

You can get your ancestors’ deeds in a number of ways. The easiest is to go to a county courthouse, archive or library that holds the original books or microfilmed copies of them. But looking for an 1840 deed in a county that wasn’t formed until 1851 is a fruitless search, so first, you need to know the county the property was in when the deed was recorded. Try the Family Tree Sourcebook (Family Tree Books) or Red Book: American State, County, and Town Sources (click the Red Book title, select a state, then click the county resource link). If you’re still not sure where to look, a call to the county courthouse can’t hurt.

Unfortunately, it’s not likely all your ancestors were considerate enough to live close to you. When you can’t get there in person, turn to the FamilySearch Library (FSL). Run a place-name search of the catalog, typing in the name of the county. Choose the correct option from the choices that pop up and look for a Land and Property heading. Click it, then examine the titles for ones that describe deed books and indexes. Click the title for more about the item; you’ll see details including the years covered by each volume or index, as well as the film number for each roll.

If you see a volume or index covering the years your ancestor purchased land in that county, click the corresponding film number to view access information. You may need to go to a local FamilySearch Center to view certain records.

If you don’t find the deed in the year you expect, expand your search to subsequent years. A deed could be recorded at the courthouse decades after the document was signed.

Many deed books aren’t posted online, although a check of your county clerk’s website and the county USGenWeb project page (click the state, then the county) certainly wouldn’t hurt. You might find an index to the county’s deeds, if nothing else. One standout example is Maryland and its free site MDLandRec.net. MDLandRec.net offers digital images of deed indexes and books for all 24 counties, dating back to the mid-1600s.

Whether you work at the courthouse or on microfilm, start with indexes if they’re available. Indexes come in different formats, so take a minute to understand how the index you’re working with is set up. Most deed indexes are consist of two separate series of books: an index by grantee’s (buyer’s) name and another one by grantor (seller). These series usually have one book for each beginning letter of the surname. For example, if you’re looking for a Smith buying land, you’d go to the grantee indexes and find the S volume.

Within the surname indexes, entries may be organized differently. Some indexes are “sounds like” indexes, organized by key letters. Some might be alphabetical by first name, and others are simply chronological—so you’d need to look through all the Smiths to find yours.

Note all the information the index gives you. (Next, we’ll go over the juicy details you might learn.) Once you’ve recorded the volume and page references for the deeds you want, it’s time to get the actual document. If you’re using microfilm, this may mean paging through more pages. It might be cheaper to mail a request to the court clerk, county recorder or other office holding the original deeds. Most offices won’t do research for you, but some will make copies (usually, for a fee) if you provide the deed volumes and page numbers.

How to Use US Land Records to Solve Family Mysteries

Laws regarding land transfers varied from place to place and evolved over time, but they defined exactly how property was to change hands: what information required at the time of recording, how land descended to heirs when someone died without a will (intestate), and more. All those details mean you can make new discoveries and solve mysteries in deed records—including these 10:

1. Was he (or she) married?

The names on a deed clue you in to the marital status of the seller. If a married person sold property, both the husband’s and wife’s names will generally appear on the deed.

The marital relationship will also be stated. Why? One reason is dower. A wife had a legal interest, usually one-third, in any property her husband owned. Most laws required the wife’s signature and approval on a deed.

Second, married women could own property, but in most cases didn’t control it. A married woman was considered feme covert—a “covered woman.” The law saw a married couple as a single entity represented by the husband. So if a deed shows a woman selling property with no mention of a husband, it’s a reasonable assumption she was single or widowed. The same may be true for men: Laws varied concerning property acquired prior to marriage, so you’ll want to understand laws governing the transaction you’re analyzing.

2. When did he die?

Most states didn’t require birth and death registration until the late 19th or early 20th century, and compliance often wasn’t good. But when people recorded deeds, they had to make statements—about dower, acknowledgement of the deed, receipt of payment and so forth. When people make statements, they may add details.

Consider the 1848 dower release of Margaret Staats, widow of Elijah Staats. Elijah’s heirs filed a quitclaim deed in Washington County, Ohio, transferring heir interest in a parcel of property to Benoni Staats, the eldest son. Margaret appeared before a judge to confirm the release of her “right of dower … to the within lot … which Elijah Staats died seized of on the 27th of September A.D. 1844.” Ohio didn’t mandate death registration until 1867, but this deed states Elijah’s date of death 20 years earlier. You never know what you’ll find until you look.

3. Why is my ancestor selling someone else’s land?

Not every land transfer was recorded at a courthouse. This is often true when property stayed in a family. Deeds cost money to record, and as long as there was no problem between folks, life went merrily along with a new landowner.

Eventually, however, the property would pass to someone who wanted to record the deed. To assure clear title to the new buyer, the seller had to document the transactions by which the property came to be in his hands. This chain of title can go all the way back to the original owner. These property histories often document family details not found elsewhere.

In 1808, Elijah Staats sold property in New Castle County, Del., that once belonged to Abraham Harman. The deed actually contains two chains of title. The first documents that Abraham Harman died intestate and his property was partitioned among his three sons. The property Elijah sold belonged to the youngest son, Benjamin Harman.

How did it come to be in Elijah’s possession? The second chain of title tells us: “… and the said Benjamin Harman died intestate and without issue, his aforesaid brothers [the other two children of Abraham Harman] being also deceased, whereupon the above described land descended to his two half brothers to wit, Richard Staats (who is since deceased and without issue) and Elijah Staats above named … ” Now there’s some helpful history.

4. Who were the neighbors?

If your ancestors lived in an area utilizing this metes and bounds survey method, you’ll encounter some zany descriptions involving landmarks such as rocks, oak trees and the lines of neighboring properties. While you might wonder what happens if someone moves the rock or the oak tree falls down, pay attention to those neighbors. They’re part of your ancestor’s circle of friends, associates and neighbors, and they could help you solve your ancestral brick walls.

For example, knowing the names in your ancestor’s social circle can help you distinguish your John Jones from the other John Joneses in the same town. It’s also a good way to identify potential maiden names: Couples had to get within kissing distance at some point, which meant our ancestors often ended up marrying the boy or girl next door.

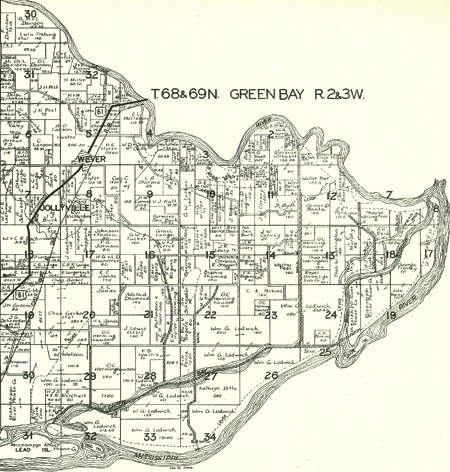

5. Where was the land?

Learning how to use a deed’s land description to draw out your ancestor’s property and locate it on a map or atlas isn’t as hard as you think—and it can reap big rewards. It lets you see your ancestor in the context of his surroundings: churches, schools and physical features of the land.

This information may help focus your search or lead you to a new record source. For example, a mountain range or river in the way may have sent your ancestor to a different church or courthouse than the one you expected.

And knowing where to find your ancestor’s land means you can take a trip (virtually via Google Earth or even better, in person) to visit the old homestead. Making a connection between words on the paper and a spot on the earth can be a powerful experience. Walking the land your ancestors walked and seeing things they probably saw provides a concrete connection to your past.

6. Where did my family come from (or move to)?

Heirs named in estate settlements didn’t always live nearby. Or a person’s property might be sold after he’d moved away. Deeds can point you to these other locations.

Heirs could appear before their local court to acknowledge the deed rather than make a long trip back to the county where the deceased’s property was located. That local court sent this acknowledgement to the court where the property was located, where it was recorded into the deed book (including the local county name), providing a valuable link between the two places.

The residence of both the grantee and grantor (usually just the county and state) are listed on a deed. Even this small bit of information can be useful as a way to prove an ancestral identity.

For example, tax and census research shows there was only one man named Elijah Staats in Fayette County, Pa., in the early 1800s. Therefore, documents recorded not only there, but also in New Castle County, Del., and Washington and Harrison counties, Ohio—all of which refer to “Elijah Staats of Fayette County, Pennsylvania”—can be connected to this one man.

7. Which guy is my ancestor?

Remember that the deeds you see in deed books aren’t the originals. After the necessary proof and acknowledgements, the judge ordered the clerk to record the deed. The clerk would then copy it into a deed book, even the signatures as they appeared on the original deed. If your ancestor was able to sign his name, the clerk copied it as it appeared.

If your ancestor could not sign his name and instead made a mark, the clerk wrote out the name and included a notation that a mark was made. Often the mark was an x, but occasionally it was something else—perhaps a first initial. By comparing signatures in records, you can determine identity. If one John Smith consistently signed his name, and another John Smith marked his documents with an S, you now have a way to theorize which transactions involve which John Smith.

8. Are the records really gone?

“Those records were lost in the fire.” What family historian hasn’t heard this line? But it’s not always true. Deeds are one of the few county records in which the original went home with someone rather than being filed at the courthouse. In the event of a fire, flood or other calamity, property records were among the first to be re-recorded. Deeds may even contain references to probate, wills, trials and other court records that actually were lost to fire—or still exist.

Aug. 5, 1837, John W. Summers signed a deed of release, transferring his interest in his father’s estate to Ebenezer Gray. The deed states “Whereas John T. Summers late of the County of Harrison and State of Ohio, deceased, did by last will and testament dated the fourteenth day of March AD 1837 give and bequeath to his second son, John W. Summers, the ballance of his estate …” This release doesn’t give us the complete picture of John T. Summer’s estate, but a little bit of a picture is better than none.

9. I can’t find a will.

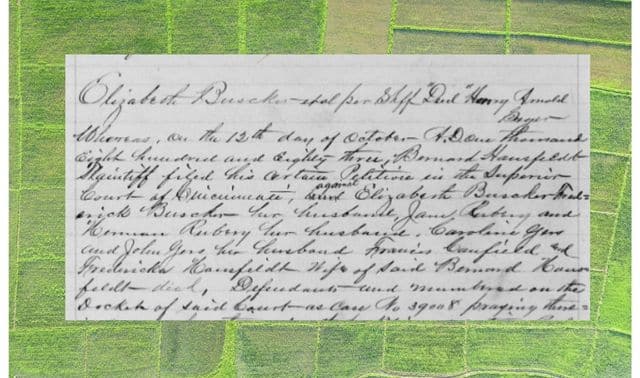

Now what? No will? No problem. One of the best things that can happen for a genealogist is that an ancestor dies intestate while owning land (sorry, ancestors—it’s true). Without a will, the laws at the time determined how inherited property was to be distributed. Accounting for those property transactions will reveal the heirs.

Ever wonder about that et. al. you noticed in the deed index? It means “and others.” You’ll see it when several heirs jointly release their interests. This can make your job easier: It’s one-stop shopping when all the heirs are listed in a single document. You also may get the married names of daughters and the spouses’ names of married sons.

10. Who are his heirs?

The 1785 probate packet of Jacob Staats Sr. in Appoquinimink Hundred, New Castle County, Del., contains only an inventory of personal property and an administrator’s bond (a record of money posted to cover possible losses due to the administrator’s misconduct). A later relative’s account indicates that the estate was split into eighths but makes no mention of the heirs. How do we figure out who they were?

Locating Staats deeds in the county sheds light on the question. Two deeds written the same day in February 1792 convey interest in land “belonging to Jacob Staats … deceased”:

- The first deed names David Staats as the grantor and Jacob Staats as the grantee.

- The second has Robert and Lydia Standley as grantors and Jacob Staats as grantee. Each transaction conveys an equal amount of interest, mysteriously described as “being an eight part or share, and the seventh of the eighth part…containing in all twenty and three acres, three roods, and one perch” (equaling just over 23.75 acres).

- A third deed, written Oct. 7, 1800, from Elijah Staats to John Callahan, clarifies things. Elijah conveys interest coming to him “by the death of my father, Jacob Staats Senior, and also my share of land coming to me by the death of my sister’s son, Jacob Irons; containing in all 24 acres more or less.”

Delaware laws explain the division of inherited land stated in the deeds: If a child died before the parent and had no heirs, that child’s share of the estate would be split equally among the parent’s remaining heirs. From these deeds, I’ve discovered that:

- Jacob Staats Sr. had seven children (under Delaware law, the eldest son received two shares, making a total of eight parts to the estate)

- The heirs inheriting full shares included: David Staats, Lydia Standley, Jacob Staats, Elijah Staats and a daughter who married someone named Irons.

- The daughter who married Irons, as well as her only child, died before Jacob Staats Sr. did, so her share was split equally among the remaining seven shares.

Most of this information isn’t in any other source. The deeds answer questions about other documents involved in the estate, and without them, we could only guess at the names of the heirs.

Finding and using deeds might require some dedication, but this rich source of data that may not appear anywhere else is well worth it. Deeds alone won’t complete the puzzle of your family’s past, but they may very well fill in a few difficult pieces.

Tip: To shake every hint of family relationships from each deed, take the time to understand laws that affected a given land transaction: Was estate distribution governed by primogeniture (the eldest son inherits everything)? Did the eldest son receive a double share? What happened when an heir was deceased? Laws varied by place and time—see the September 2011 Family Tree Magazine for advice.

A version of this article appeared in the September 2012 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated, December 2024.