Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Text written by Maureen A. Taylor unless otherwise noted.

In this article:

- King Philip’s War

- French and Indian War

- Quasi-War with France

- War of 1812

- Texas War of Independence

- Mexican-American War

- Utah War

- Indian Wars

- Spanish-American War

- Philippine Insurrection

- Military Microfilm Titles at the National Archives

If America’s historical military conflicts could have sibling rivalry, they’d all be jealous of the Revolutionary War, the Civil War and World Wars. Information abounds about how to research ancestors who served in these wars—as you might expect, because of the masses who fought and the comparatively heavy toll taken on our country.

But less-famous conflicts, such as the Mexican War and Indian Wars, were just as devastating to those who fought and died. Genealogical records of those soldiers are no less telling than records of the “wars of the century.”

Of course, the notoriety of the Revolution, Civil War and other large-scale conflicts makes their records more accessible. Finding resources for other wars will require digging for details, studying US history and requesting offline records. But you can do it—and we’re here to help, with our guide to finding genealogy records of 10 “small” military conflicts.

Military Record Search Strategies

Knowing where to look for military records is half the battle. If an ancestor fought in a Colonial war—that is, any war taking place before the American Revolution—you’re more likely to locate state militia pay lists, muster rolls and military hospital records in state archives and military historical societies covering the war or the place where your ancestor enlisted. For example, the New England Historic Genealogical Society has a subscription database of over 36,000 names of New England soldiers and officers from 1620 to 1775. It’ll be easier to find records if you can learn which regiment or company your ancestor was part of.

If your ancestor was in the British Army, you may find information at the British National Archives in Kew. See its muster rolls and pay lists finding aid and information on additional British Army records.

For most wars after the Revolution and the birth of the federal government, you’ll consult the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), which has compiled service records, pension files and other federal records. Surviving service and pension records are on microfilm and/or paper at NARA. The FamilySearch Library and other large libraries may have copies of NARA microfilm. If you need to order NARA records that aren’t microfilmed; you’ll need to know the soldier’s name, the war he served in and his state of residence.

Because many records have been indexed or digitized, though, start your search online. For example, Ancestry has a digitized version of NARA microfilm T288, General Index to Pension Files, 1861–1934, as well as books of transcribed muster rolls and rosters. (Your library may offer Ancestry Library Edition free.) Ancestry.com’s sister-site Fold3 also has many indexed and digitized records from NARA. Olive Tree Genealogy and Online Military Indexes may direct you to other online sources.

The fact that not everything is online hurts a bit more for lesser-known wars: shorter campaigns and fewer soldiers mean fewer descendants clamoring for records. You’ll find yourself scrolling microfilm, turning book pages and penning record requests. The FamilySearch Wiki gives an overview of each war in this article, with links to records you can access on microfilm through the FamilySearch Library. Just type the name of the conflict into the search box.

Search WorldCat, a catalog of thousands of libraries’ holdings, for books with indexed records from the war you’re interested in. Borrow titles from your library or through interlibrary loan. Seek publications of groups such as the General Society of Colonial Wars. Also look for regimental histories in book collections on HeritageQuest Online (available through subscribing libraries), Ancestry and Google Books.

(Some) Colonial Conflictions Involving the English Empire

The early colonial wars involving England in North America are too numerous to cover individually, but their impact on the continent’s political and social development was profound, long before the American Revolution. The conflicts often involved not just colonists, but indigenous nations and European powers. While we have chosen to highlight a few lesser-known wars, the following resources provide broader coverage across multiple early conflicts:

FamilySearch has digitized microfilm from the Connecticut archives of selected papers of colonial wars including King Philip’s War, King William’s War, Queen Anne’s War, the Eastern Indian War, War with Spain, King George’s War and the French and Indian War. There is also the digitized collection “French and Indian War muster roll index cards, 1603-1779” from the Massachusetts State Archives on FamilySearch.

American Ancestors’ “French and Indian Wars Manuscripts” collection contains manuscripts related to the French and Indian Wars, including King William’s War, diaries, letters, military records and more materials that provide details on the experiences of those who fought in the French and Indian Wars in North America.

Books: Narratives of the Indian Wars, 1674-1699 by Charles Henry Lincoln; Massachusetts Officers and Soldiers in the Seventeenth Century Conflicts edited by Carole Doreski (Society of Colonial Wars in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts).

The General Society of Colonial Wars was established in 1892. Membership in the society requires that the member be a male at least 18 years old and able to show direct lineage to an ancestor who served in a colonial war. FamilySearch has registers of members, lineage papers, and supplemental records of the society. However, access may be limited unless accessing at the FamilySearch Library or a FamilySearch Center. An index of ancestors and roll of members, published in 1922, is available for free on Google Books.

Text contributed by Katharine Korte Andrew

King Philip’s War

Years: 1675 to 1676

Overview: In 1675, Wampanoag leader Metacomet (known to the English as King Philip) organized several southern New England tribes against the colonists after three Indians were executed for killing a colonist. Half of New England’s towns saw armed conflict. In King Philip’s War: The History and Legacy of America’s Forgotten Conflict (Countryman Press), authors Eric Schultz and Michael J. Tougias estimate that more than 1 percent of colonists and 15 percent of the American Indians involved died. King Philip was killed in August 1676, yet the war continued in northern Maine (then part of Massachusetts) until a treaty was signed at Casco Bay in 1678. Learn more at the Society of Colonial Wars for Connecticut website.

Genealogical Resources: Lists of participants and deaths are in publications such as King Philip’s War by George William Ellis and John Emery Morris and The History of the Great Indian War of 1675 and 1676 by Benjamin Church, Thomas Church and Samuel Gardner Drake (access both on Google Books).

Soldiers in King Philip’s War by George Madison Bodge (reprinted by Genealogical Publishing Co.) has more than 5,000 names from muster rolls, payrolls, biographical and genealogical sketches and other records.

The state archives or libraries of Rhode Island, Connecticut and Massachusetts may have town or colony documents prosecuting military actions, muster rolls and interactions with Indians. The Massachusetts State Archives has a database of Colonial records from 1629 to 1799. Type in a name and choose King Philip’s War from the drop-down menu; you’ll get a summary of the record and information on its location at the archives.

King William’s War

Years: 1688 to 1697

Overview: King William’s War, also known as the Second Indian War or the War of the Grand Alliance, was the first of six colonial wars fought between New France and New England, along with their respective Native American allies. The war was the North American theater of the Nine Years’ War, which pitted France against the Grand Alliance comprised of England, Scotland, the Dutch Republic, the Holy Roman Empire, the Spanish Empire, and the Savoyard state.

Genealogical Resources: During the war, many colonists served in local militias that were not part of the British Army. Because of these being local units, most surviving records are held by local historical societies, state libraries or local/state archives.

The Border Wars of New England: Commonly Called King William’s and Queen Anne’s Wars by Samuel Adams Drake (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1897) is a 19th century history book that gives background to King William’s and Queen Anne’s Wars, and context, including details about some local militias and individual actions taken by colonists. Similarly, Early History of New England; being a relation of… also a detailed account on the origin of the war with King Philip by Increase Mather and Samuel G. Drake (1864) is also available on the Digital FamilySearch Library.

King William’s War: The First Contest for North America, 1689-1697 by Michael G. Laramie (Westholme Publishing) won the New York Society of Colonial Wars annual book award and is one of the few modern historiographies of King William’s War and this relatively obscure time in colonial history.

Text provided by Katharine Korte Andrew

Queen Anne’s War

Years: 1702 to 1713

Overview: Queen Anne’s War, also known as the Third Indian War, was another in a series of the French and Indian wars fought between the colonial empires of Great Britain, France and Spain along with their respective Native American allies. It was also the North American theater of the War of the Spanish Succession. During the war, many colonists served in local militias and were not part of the British Army. Significant events during this conflict include: in 1702 the South Carolina militia destroyed the Spanish town of St. Augustine in Florida; the French and Spanish attacked Charlestown, South Carolina in 1706; and the British captured Port Ryal in Acadia, now Nova Scotia, from the French in 1710.

As a result of the peace terms, the British gained the territories of Newfoundland, Nova Scotia and the Hudson Bay area, while the French kept control of New France and fishing rights in Newfoundland.

Genealogy resources: During the war, many colonists served in local militias that were not part of the British Army. Because of these being local units, most surviving records are held by local historical societies, state libraries or local/state archives.

Here are some recommended reads on Queen Anne’s War:

- The Border Wars of New England: Commonly Called King William’s and Queen Anne’s Wars by Samuel Adams Drake (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1897)

- Roll and journal of Connecticut Service in Queen Anne’s War, 1710-1711 (Tuttle Morehouse & Taylor Press)

- Massachusetts officers and soldiers, 1702-1722: Queen Anne’s War to Dummer’s War edited by Mary E. Donahue (Society of Colonial Wars in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts)

Text provided by Katharine Korte Andrew

Regulator Movement in North Carolina

Years: 1766-1771

Overview: The Regulator Movement, also known as the Regulator Insurrection or War of Regulation, was an uprising among citizens in colonial North Carolina from 1766 to 1771 driven by citizens who opposed what they saw as widespread corruption among colonial officials. The Regulators wanted better economic conditions for everyone challenging a system that disproportionately favored the colonial officials and their network of plantation owners near the eastern coast. Though tensions and sporadic violence took place across most of North Carolina’s western counties, the conflict culminated in a single major clash: the Battle of Alamance on May 16, 1771.

Genealogy resources: There were several different documents and petitions circulated to promote the end of taxation and other issues. Some influential members of communities signed petitions. Some of these documents can be found on the site Documenting the American South. NCpedia also has the documents transcribed and digitized related to the Regulators, including this 1768 petition.

A list of known Regulators exists on the Quaker Ancestors site for the Cane Creek Monthly Meeting.

Existing digitized records related to the Regulator Movement can be found in the North Carolina Digital Collections “Regulator Movement” collection. Per the website, this collection “contains military unit accounts, receipts, court and trial records, expense accounts, warrants, prisoner records, payrolls, order books, and other records from this movement.”

Text Provided by Katharine Korte Andrew

French and Indian War

Years: 1754 to 1763

Overview: The French and Indian War is the North American component of the Seven Years War, a series of worldwide conflicts between Great Britain and France. Though the war’s name refers to the French and their Indian allies, native tribes participated on both sides. Battlefields stretched along the frontier of French and British colonies from Nova Scotia south to Virginia. After a series of disastrous campaigns in 1757, Britain managed to turn the tide of the war by capturing Montreal in 1760.

The war resulted in Britain’s colonial dominance in North America. The Treaty of Paris required France to cede Canada to Great Britain (with the exception of two coastal islands) and transfer Louisiana west of the Mississippi to Spain. Great Britain also gained control of Florida from the Spanish. France would regain control of Louisiana, then sell it to the United States as the Louisiana Purchase. For more information, see Robert Leckie’s A Few Acres of Snow: The Saga of the French and Indian Wars (John Wylie) and peruse the site for PBS’ “The War That Made America”.

Genealogical Resources: Militia muster rolls and pay lists are among the documents you can find in colonial papers at the various state archives in which the soldier lived or served. A colonial militia collection at the Rhode Island Historical Society contains official state records of the French and Indian War. Also look for published indexes, such as Virginia’s Colonial Soldiers by Lloyd DeWitt Bockstruck (Genealogical Publishing Co.), which indexes sources including muster rolls, court martial records and more.

Quasi-War with France

Years: 1798 to 1800

Overview: After the American Revolution, the United States declared neutrality in the conflict between Britain and France, eventually signing the Jay Treaty with Britain. Combined with the US refusal to repay debts to France (they were owed to the crown, claimed America, not the new French Republic) tensions escalated into an undeclared naval war. France intercepted vessels trading with Britain; the United States hastily raised a navy in response. The Convention of 1800 halted the hostilities.

Genealogical Resources: For officers’ service information, search Ancestry.com’s database Officers of the Continental and US Navy and Marine Corps, 1775-1900, or look for the 1901 book of the same name, edited by Edward W. Callahan. NARA microfilm M330 contains abstracts of service records of naval officers from 1798 to 1893 and is also available on FamilySearch.

US citizens may have filed against France, Spain or Holland to reclaim ships and property seized during this conflict. If you had an ancestor involved in trade, see NARA’s online article on these French spoliation claims and the resulting records.

War of 1812

Years: 1812 to 1815

Overview: US and British differences didn’t stop after the American Revolution. British trade restrictions, impressment (capture and forced service) of American sailors into the Royal Navy, and England’s alliance with American Indian tribes caused continued tensions. Britain blockaded Atlantic seaboard ports, attacking Navy and merchant vessels. Naval battles took place in the Great Lakes, Gulf of Mexico and St. Lawrence River. Francis Scott Key penned the “Star Spangled Banner” after observing the American defense of Fort McHenry in Baltimore. The treaty of Ghent ended the war in December 1814, though battles continued into the next year until the news crossed the Atlantic.

Genealogical Resources: Records are plentiful for this “second war of independence.” War of 1812 compiled military service records are indexed on NARA microfilm M602, as well as on Ancestry.com. The actual records aren’t filmed, so you’ll need to order copies from NARA. You won’t find much in the way of service records for Army officers, but look for their names in Historical Register and Dictionary of the U.S. Army by Francis B. Heitman (Genealogical Publishing Co.). For Naval officers, see NARA film M330.

Many pension applications date from decades after the war, as Congress passed laws allowing veterans or their widows and children to apply. The “Old Wars” pensions cover service resulting in death or disability from the end of the Revolutionary War until the Civil War. Most War of 1812 soldiers in this group were volunteers or members of state militia that were federalized during the war. Their names are arranged alphabetically by veteran on NARA microfilm T316.

An 1871 law covered veterans who served at least 60 days or their widows (if the couple was married before 1815). An 1878 law included men who served at least 14 days. You’ll find an index to these later pensions on NARA microfilm M313 and transcribed in Index to War of 1812 Pension Files by Virgil D. White. War of 1812 pensions are being added to Fold3 in the “Preserve the Pension” project. For more details, see NARA’s article.

As for the American Revolution, Uncle Sam issued bounty land warrants to pay War of 1812 veterans. Both wars’ warrants are grouped on NARA microfilm M848 and in Ancestry.com’s database of US War Bounty Land Warrants, 1789-1858.

If your ancestor was involved in the maritime trade, search Footnote’s collection of War of 1812 Prize Cases from the Southern District Court of New York. Digitized from NARA microfilm M928, these files relate to maritime property seized at the country’s leading port from 1812 to 1816.

Two NARA microfilms cover impressed seamen from 1793 to 1802: M2025 has registers of applications for their release, and M1839 has miscellaneous documents. Merchant seaman had to register with customs officials at their ports. If your ancestor served on a merchant ship, check these Seaman Protection Lists at the NARA location covering the port of registration. Rhode Island certificates are at the Rhode Island Historical Society; find an index in Register of Seamen’s Protection Certificates from the Providence, Rhode Island Custom District 1796-1870 (Clearfield Co.). Extracted information for Waltham, Mass., certificates is online at the Mystic Seaport Museum.

A resource called the Draper Manuscripts, housed at the Wisconsin Historical Society, is full of Revolutionary War and War of 1812 information. The interviews, letters, maps and other documents relate to the western Carolinas and Virginia, some portions of Georgia and Alabama, the Ohio River valley, and parts of the Mississippi River valley. Consult Guide to the Draper Manuscripts by Josephine L. Harper (Wisconsin Historical Society) for details. The FamilySearch Library and other large libraries have microfilm copies of much of the collection.

Texas War of Independence

Years: 1835 to 1836

Overview: The rousing declaration “Remember the Alamo!” comes from this conflict. Mexican Gen. Antonio López de Santa Anna abolished the Constitution of 1824, setting off a war between Mexican troops and American settlers (called Texians) in what was then part of Mexico. It lasted from Oct. 2, 1835 to April 21, 1836, with additional conflicts occurring into the 1840s. The independent Republic of Texas was established in 1836 (it became a US state in 1845). Find more information on the Texas Military Museum website and in The Texas War of Independence, 1835-1836: From Outbreak to the Alamo to San Jacinto by Alan Huffines (Osprey Publishing).

Genealogical Resources: Because Texas wasn’t part of the United States when this war occurred, you won’t look to NARA for records. Instead, you’ll use published indexes and the Texas state archives.

You’ll find a Texas army roster at earlytexashistory.com/Tx1836/txindex.html. Muster Rolls of the Texas Revolution (Daughters of the Republic of Texas) contains soldier names. Look for pension details in Republic of Texas Pension Application Abstracts by John C. Barron (Austin Genealogical Society). Volunteers are transcribing pension papers at The USGenWeb Archives Pension Project: Republic of Texas; you’ll find information on the claims and a searchable index on the Texas State Library and Archives website. The pension records are on microfilm at the Texas archives and the FamilySearch Library. Historical information on the siege of the Alamo and those who served appears in Roll Call at the Alamo by Phil Rosenthal and Bill Groneman (Old Army Press).

Mexican-American War

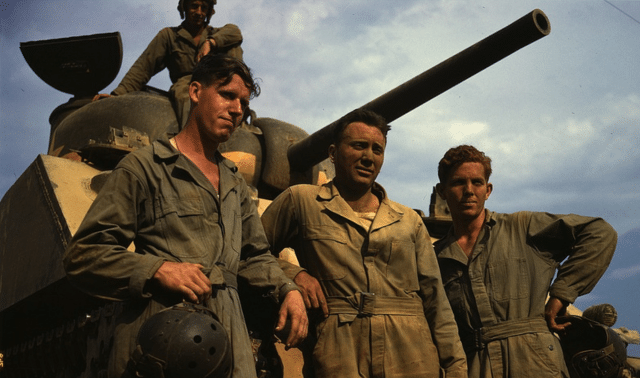

Years: 1846 to 1848

Overview: Mexico refused to acknowledge Texas independence, so a year after Texas became a state, the United States and Mexico were at war. The US Navy blocked Mexican ports; the Army invaded Mexico and its northern territories. The war led to what’s known as the Mexican Cession: Mexico sold its land in what’s now California, New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, Utah and Nevada to the United States for $15 million. Get more details on the Son of the South website.

Genealogical Resources: Texas and Illinois provided the most regiments, but only a few New England states didn’t send any units to war. First, check the microfilmed indexes to Mexican War pensions (NARA microfilm T317) and service records (M616). NARA and the FamilySearch Library have microfilmed service records for Texas volunteers and those from several other states; if you don’t find film for your ancestor’s state, you’ll need to order the records from NARA.

The Descendants of Mexican War Veterans offers more statistics and recommended reading. Look online for indexes, too, for instance, a list of Pennsylvania men who fought in the Mexican War. Search for Americans buried in the Mexico City cemetery at the American Battle Monuments Commission website.

Utah War

Years: 1857 to 1858

Overview: President Buchanan sent troops to enforce his choice for a non-Mormon governor in Utah Territory, heavily populated by Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints members. No formal battles took place; instead, clashes between settlers and troops claimed lives. For more details, see Causes of the Utah War by William P. MacKinnon (Fort Douglas Vedette) and the Utah History Encyclopedia.

Genealogical Resources: From 1849, the Constitution of the Provisional State of Deseret required men between the ages of 18 and 45 to participate in the Utah militia. Most Utah militia records are in Utah Territorial Militia Muster Rolls, 1849 to 1870 (FamilySearch films 485554 to 485558). Younger boys and older men also could join. On the US side, Army “regulars” (those who already were in the Army, rather than soldiers who enlisted for a specific war) did the fighting. Look for their names in NARA microfilm M233, listing US Army enlistments from 1798 to 1914; the database also is on Ancestry.com.

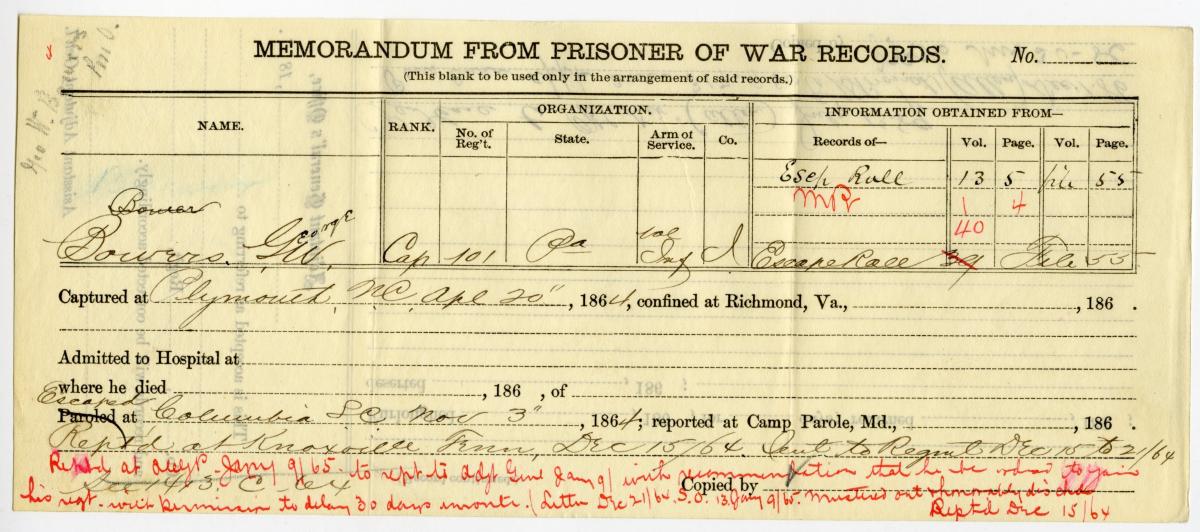

Indian Wars

Years: 1860 to 1900

Overview: Failed treaties and pressure from the encroaching US population led to a series of frontier wars between the United States and Indian nations, especially during the late 1800s. Notable conflicts include the Sioux Wars in the Dakotas, which saw the death of Gen. George Custer at the Battle of the Little Big Horn. The massacre at Wounded Knee in 1890 was the last armed conflict of the Sioux Wars. In the Southwest, Geronimo led the Apache against US troops. Several US African-American regiments in these wars came to be called Buffalo soldiers. The US also employed Indian scouts.

A timeline such as the one on Wikipedia can help you keep track of all the battles that raged during this tumultuous period.

Genealogical Resources: Many men who served with these units were in the regular Army; they’re named in the previously mentioned enlistment registers microfilm M233, also on Ancestry.com.

Veterans of Indian Wars from 1859 to 1891 could apply for pensions under a Congressional act of March 4, 1917. For pension records from these wars, see NARA microfilm T288, General Index to Pension Files, 1861–1934 (also on Ancestry.com). Virgil White’s Index of Pension Applications for Indian Wars from 1818 to 1898 (National Historical Publishing Co.) also is a useful resource. You’ll need to order copies of pension records from NARA.

For information on Indian scouts, see the NARA article. NARA has records of Buffalo soldiers as well.

Spanish–American War

Year: 1898

Overview: When the American battleship Maine mysteriously sank in Havana harbor in 1897, the already-extant political tension between Spain and the United States escalated into a war with Cuban independence at the center. Fighting—some by Teddy Roosevelt’s famous Rough Riders—took place in Spanish holdings in the Caribbean and Pacific. The Treaty of Paris gave the United States and colonial authority over Puerto Rico, Guam, the Philippines and (temporarily) Cuba for $20 million. See related documents, information and photographs at the Library of Congress website.

Genealogical Resources: This NARA article is a great resource for learning about Spanish-American War records. Service records are indexed on NARA film M871, General Index to Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Soldiers Who Served During the War with Spain. You’ll need to order the actual records from NARA.

You can find an index to the First Volunteer Cavalry—aka Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders—on AccessGenealogy. Their service records are digitized in NARA’s Archival Research Catalog, which you can access through the FamilySearch Wiki.

Veterans who applied for pensions may be listed in the previously mentioned NARA microfilm T288 (also digitized on Ancestry). The pension records themselves aren’t microfilmed; you’ll need to request them from NARA.

The US Navy (on whose ships African Americans and Asian immigrants were integrated with other sailors) played a large part in this conflict. You’ll find ships rosters on the Spanish American War Centennial website. Naval compiled military service records start in the late 19th century; only officers’ records are microfilmed on films M330 and M1328.

Female ancestors might have served as nurses working under contract with the Army. Records on paper at NARA include Personal Data Cards of Spanish-American War Contract Nurses.

Philippine Insurrection

Years: 1899 to 1902

Overview: In this war, Filipinos sought independence from the United States, which had received the islands after the Spanish-American War. The Philippine government surrendered July 4, 1902. The United States granted the islands autonomy in 1916 and independence in 1946. For more details, see archives.gov/publications/prologue/2000/summer/philippine-insurrection.html.

Genealogical Resources: About 125,000 US troops—both Army regulars and new volunteers—served in the war. You’ll find the regulars named in the microfilm and Ancestry database Registers of Enlistment in the US Army, 1798-1914. Volunteers who fought in state regiments were in units from the Spanish-American war; you’ll consult service records of that war to learn about these men.

The 1900 census contains information on military personnel stationed in the Philippines, Cuba and Puerto Rico. On Ancestry.com, Military and Naval Forces is the place of residence. Service records of US volunteers are indexed in NARA microfilm M872, Index to Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Soldiers Who Served During the Philippine Insurrection. Order copies of the records themselves from NARA. Look for Marines who fought in the Phillippines in the Ancestry database of Marine Corps muster rolls dating from 1893 to 1940.

Pensions were first granted to Philippine Insurrection veterans in 1922. An index to veterans who applied is in the aforementioned General Index to Pension Files, 1861–1934. The pension files haven’t been microfilmed; you’ll need to request them from NARA.

Military Records at the National Archives

Here’s a rundown of the NARA microfilm titles you’ll want to consult for researching those who served in the United States’ lesser-known military conflicts—Quasi-War with France, War of 1812, Mexican-American War, Utah War, Indian Wars, Spanish-American Wars and the Philippine Insurrection. You can look for copies at the Family History Library or find out whether a title is digitized on Ancestry or Fold3 by checking NARA’s list of Microfilm Publications Digitized by Partners.

- M233: Registers of Enlistment in the US Army, 1798-1914

- M330: Abstracts of Service Records of Naval Officers, 1798-1893

- M1328: Abstracts Of Service Records of Naval Officers, 1829-1924

- M848: War of 1812 Bounty Land Warrants, 1815-1858

- M313: Index to War of 1812 Pension Application Files

- M928: Prize and Related Records for the War of 1812 of the US District Court for the Southern District of New York, 1812-16

- M2025: Registers of Applications for the Release of Impressed Seamen, 1793-1802

- M1839: Miscellaneous Lists and Papers Regarding Impressed Seamen, 1796-1814

- T316: Old War Index to Pension Files, 1815-1926

- T317: Index to Mexican War Pension Files, 1887-1926

- T288: General Index to Pension Files, 1861-1934

- M616: Index to Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Soldiers Who Served During the Mexican War

- M278: Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Soldiers Who Served During the Mexican War in Organizations From the State of Texas

- M351: Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Soldiers Who Served During the Mexican War in Mormon Organizations

- M638: Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Soldiers Who Served During the Mexican War in Organizations From the State of Tennessee

- M863: Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Soldiers Who Served During the Mexican War in Organizations From the State of Mississippi

- M1028: Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Soldiers Who Served During the Mexican War in Organizations From the State of Pennsylvania

- M871: General Index to Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Soldiers Who Served During the War with Spain

- M872: Index to Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Soldiers Who Served During the Philippine Insurrection

Ordering Microfilm

If the records you need aren’t on microfilm, you’ll have to hire a researcher to get them for you, or request them from NARA. You’ll find a list of local researchers on NARA’s website, or you can use the Association of Professional Genealogists online directory.

NARA has a nifty Order Online system to help you request records from afar. Log in (if you have an account) or create a new account. Then you’ll click Order Reproductions, select Military Service and Pension Records, and follow the system’s prompts. You also can order records by mail using NARA’s downloadable order forms.

Depending what records you need, it may be more cost-effective to hire a researcher than to order from NARA. See the full fee schedule at archives.gov/research/order/fees.html.

Tip: Your ancestor’s state archives or historical society may have records of his military service, especially if he served in a state militia or guard, or in a state unit that was federalized during wartime.

Tip: To see a list of NARA’s military records microfilm, go to eservices.archives.gov/orderonline; click Microfilm at the top of the page, click Advanced Search, select Military Service Records from the Subject Catalog pull-down menu, and click Search.

Related Reads

A version of this article appeared in the December 2010 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: May 2025