Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

US military draft records are potentially untapped sources of information on male ancestors and sometimes their female family members. Even men who didn’t serve in the military may have had to register under one of the conscription acts for the Civil War, World War I, or World War II.

Online resources make it easy for today’s savvy researcher to find and use draft records as a springboard for family history discoveries. We’ll give you an overview of registration records created between 1862 and 1945, identify where to find them, and explain how to expand on the information they provide.

Clues in Draft Records

Local districts or boards conducted draft registrations to identify men eligible for service in times of war—specifically, the Civil War and World Wars. Many of the registration lists and cards these boards created survive, providing a deep well of data on several generations of American men. Those born as early as 1816 and as late as 1920 could’ve been eligible to be drafted for one or more of these three wars.

Questions the draft boards asked registrants varied from war to war, and even from one registration to the next. Typically, you’ll find information about the registrant’s name, residence, age, date and place of birth, race, US citizenship and occupation.

Depending on the registration, you also may discover details about your ancestor’s previous or current military service, his marital status, the name and address of a relative or contact person, a physical description, and his signature.

These findings can move your research forward in many ways. Birth information can tell you about births that occurred long before a state began keeping vital records. A woman named as a man’s nearest relative might narrow your search for a marriage record. An immigrant’s claim to be a US citizen could lead to naturalization papers.

Draft information is also useful in combination with other evidence. Residence and occupation details can distinguish your relative from others with the same name. If you’re “missing” a person in census records, a draft registration can indicate where he lived. Descriptions of height, build, hair and eye color can help you visualize your ancestor.

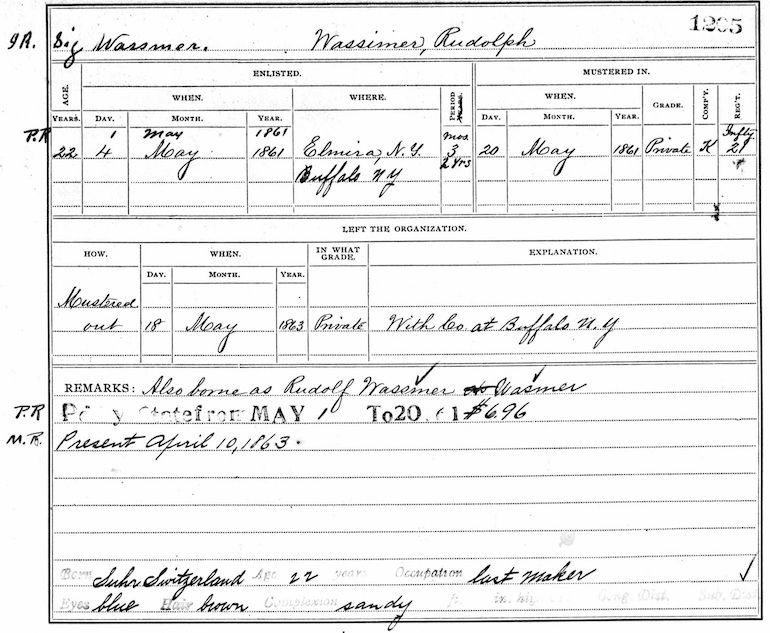

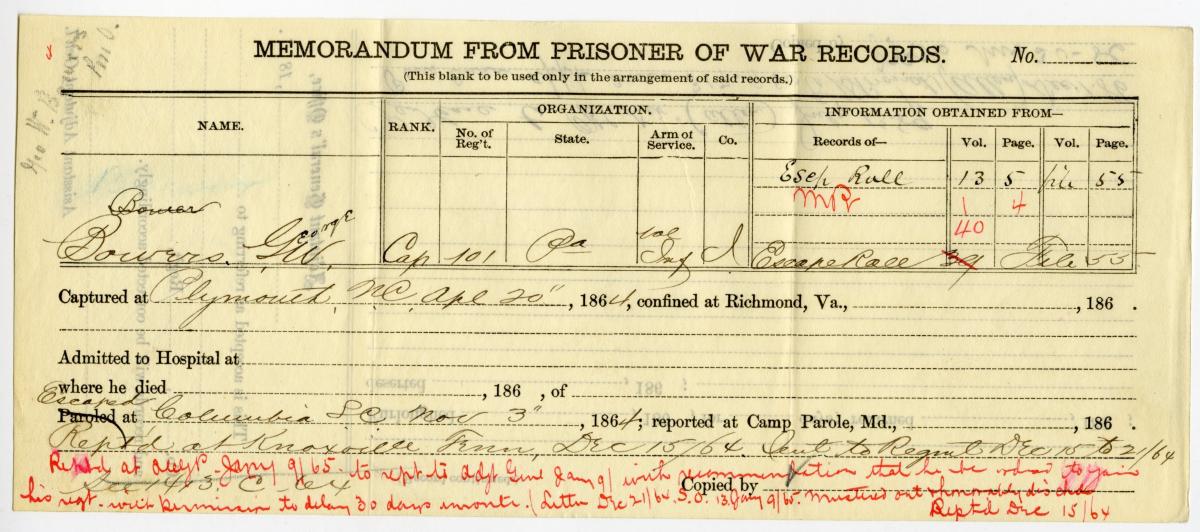

Civil War Draft Records

Prior to the Civil War, the federal and state governments relied on offering free public land to attract volunteer soldiers in wartime. These bounty land incentives were discontinued by 1855.

The Civil War brought an unprecedented need for troops on both the Union and Confederate sides. Governors from Maine to Mississippi issued calls for volunteers beginning in 1861. As the war escalated, the need for men reached crucial heights.

Without the promise of free land to spur recruits (an incentive in previous wars), how could this demand be met?

Although the idea of a national draft faced considerable opposition in the North, it seemed the only viable solution. The Enrollment Act of 1863 required all men age 20 to 45 to register within their Congressional District, which often covered several counties.

The first Union registration took place 1 July 1863. Three smaller enrollments followed. For eligibility purposes, men were divided into classes. Those age 20 to 35 years, plus unmarried men age 36 to 45, were designated Class I. Nearly everyone else was Class II.

In addition to name and residence, Northern draft registers typically show:

- age on the registration date

- race

- occupation or trade

- whether married

- state or country of birth

The registrations were assembled into consolidated lists, many of which survive. You can find digital images of existing consolidated lists on subscription site Ancestry.com (which you can use free at libraries offering Ancestry Library Edition). For more-focused results, search within the site’s US Military Records collection. As a starting point, enter your ancestor’s name and where you think he lived in 1863.

The original consolidated lists are in Record Group 110 (Records of the Provost Marshal General) at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in Washington, DC. The registration books from which they were compiled, which sometimes contain additional information, haven’t been microfilmed or digitized. They’re held at NARA’s regional branches.

If your ancestor registered, does that mean he served in the war? Not necessarily. Those in Class II were rarely made to serve. Each community and state was responsible for filling a quota of men. If they could raise that number with volunteers, no one needed to be drafted, so volunteers were heavily encouraged. Some states, like Massachusetts and Ohio, never had to call up draftees.

Even if they were drafted, men could be exempted from service if they were:

- physically or mentally impaired

- only sons of dependent widows or infirm parents

- widowers or orphans supporting young children

- non-citizens who hadn’t declared intent to naturalize

- convicted of a felony

- able to furnish a substitute or pay a $300 fee

The South also instituted a draft. The Confederate Conscription Act of 1862 required all white males age 18 to 35 years to register. This was extended to ages 17 to 50 by early 1864. Ministers, teachers, civil officials, tradesmen, railroad workers and plantation owners were typically exempt. Initially, a man could hire a substitute and pay up to $1,000 to avoid service, but that allowance was scrapped in late 1863 due to bitter opposition. Men already enlisted for one-year terms automatically saw their service extended to three years.

There are no consolidated lists of Confederate registrations. Each Southern state conducted its own drafts. Many times, troops raised by conscript were merged with existing units. Relatively few Confederate conscription registers survive today, and those that do can be difficult to find.

The best place to begin your search for any existing Southern conscription records is in the state adjutant general’s records. Some states compiled and published adjutant general records after the war. Georgia, for instance, published six volumes of The Confederate Records of the State of Georgia, which are available free on Google Books.

If your ancestors lived in Tennessee, search the Civil War Sourcebook, a digital collection of official records, diaries, letters and newspaper articles. South Carolina Archives offers information about its Confederate Military Records as well.

Learn more about Civil War records for individual states, North or South on FamilySearch.

World War I Draft Records

The need for a national draft emerged again in 1917 when the United States entered the Great War. In response, Congress created the Selective Service System, consisting of local and state draft boards under the Office of the Provost Marshal.

Three registrations took place in 1917 and 1918. In total, about 24 million men between the ages of 18 and 45, including noncitizens, were required to register. If your relative was born between September 1872 and September 1900, he was probably among them.

A draft board official asked questions of each man and recorded the answers on individual, two-sided cards. The questions varied by registration, but in general noted:

- name and age

- address

- date and place of birth

- citizenship status

- occupation and employer

- race and physical description

Some registrations also asked marital status, the name and address of the man’s nearest relative, his father’s birthplace, or information about dependants. Unless he was illiterate, the registrant signed his card to verify accuracy.

Tip: If a WWI registrant was African-American, the registrar was to tear off the lower left corner of his draft card.

Draft boards used the cards to determine which men to call up for service. They kept docket books listing the names and actions taken. Only a small percentage of those who registered were actually drafted.

Because they cover nearly 98 percent of the male population between 18 and 45 years old, WWI draft cards represent a tremendous resource for genealogists. Even if your ancestor didn’t have to register, he or she might’ve had a brother who did. The cards can reveal unknown birth dates and places, the names of wives and/or parents, and clues to marriages and naturalization.

Digital images of WWI draft registration cards are online at Ancestry.com, Findmypast and the free FamilySearch. When searching these sites, start by entering your ancestor’s name and likely residence at the time of registration. If you get too many results, filter them by adding a probable birth year and/or state. If you get too few, try variant name spellings. (You can use the asterisk wildcard to substitute for zero or more letters.) Each record consists of two images, the front and back of the card—be sure to view both.

The original registration cards are in Record Group 163 at the National Archives branch in Atlanta. Local docket books, classification lists, and miscellaneous papers relating to draft records may be found in state archives or National Archives regional locations.

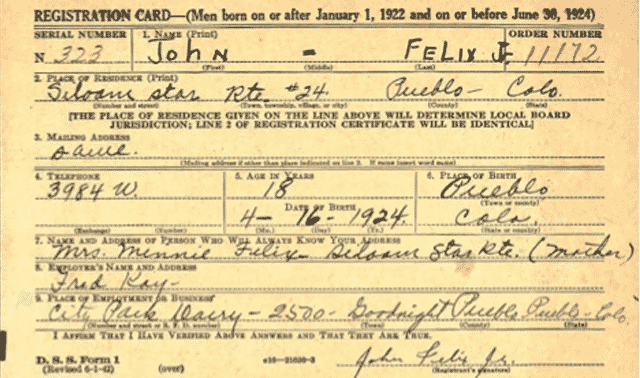

World War II Draft Records

When the Great War ended, so did military registration. There was no ongoing US draft in the 1920s and 1930s. Then escalating world conflict led to the first-ever peacetime registration in October 1940.

Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941, thousands of men voluntarily enlisted in the service. But with war raging on multiple fronts, the need for soldiers, airmen, and sailors was far greater. Congress passed a new Selective Service Act requiring all males between ages 18 and 45 to register.

WWII registrations of young men were long withheld for privacy reasons, but are now available online. Ancestry.com has a collection of full-color digital images for every US state except for Maine (whose records were destroyed before digitization could begin).

The fourth registration, conducted 27 April 1942, required men born between 28 April 1877 and 16 February 1897 to register. These men were 45 to 64 years old at the time. Nicknamed the “Old Man’s Draft,” this registration included many who’d already served—or at least registered—for World War I. Its intent was to gather information about older men’s skills and occupations that could be utilized in manufacturing, transportation and other aspects of the war effort.

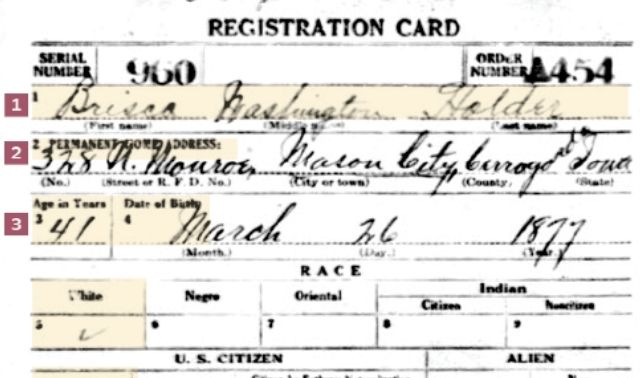

As for the First World War, registrants’ answers to several questions were recorded on two-sided cards:

- name and age

- date and place of birth

- residence address

- telephone number

- place of employment or business

- employer’s name and address

- name and address of a contact person

- race and physical characteristics

The “Old Man’s” registration cards for most states have been microfilmed and digitized. You’ll find collections on Ancestry.com, FamilySearch and Fold3. On any of these sites, start with a general name and place search, being aware of possible spelling variations. Narrow your search with additional fields, such as birthplace and year, if necessary.

Keep in mind that you should find two images for a single registrant. The cards for some states were microfilmed in such a way that the front of one man’s card appears with the reverse of the previous man’s card, so take particular care to get the right match when working with the records of those states.

These collections aren’t complete, however, as registration cards for some states were destroyed before being microfilmed. No Fourth Registration records survive for Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina or Tennessee. For New York, only those from the boroughs of New York City survive. Other states or parts of a state may be missing from a particular database. If you don’t find the results you expect, read the notes that accompany the database to learn about its coverage.

The original cards for all six WWII draft registrations are at NARA’s National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) in St. Louis. They’re divided into two groups: one for the Old Man’s Draft, and one for the other five drafts of younger men. You can request a copy of an individual’s card using the Selective Service Record Request form.

Sample Draft Records

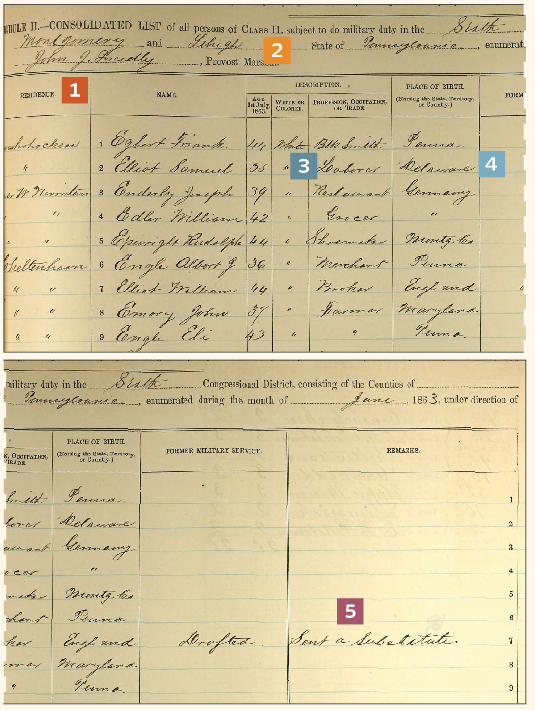

Civil War Draft Record (Union)

Let’s take a closer look at the information available in a draft record. The citation for this image can be found in the caption below. Look at the entry for each number to see where each piece of information appears on the record.

1. This list (which is shown split into halves for larger viewing) was compiled in Pennsylvania’s Montgomery and Lehigh counties in June 1863. Registrants’ names are grouped by township.

2. Class II lists named primarily married men between ages 35 and 45. Younger and unmarried men were in Class I.

3. Occupation can help identify ancestors. Compare this listing of Samuel Elliot, laborer, to 1860 and other census records.

4. Place of birth offers clues to where men came from. Samuel Elliot may appear in Delaware records.

5. Union Civil War draftees could pay a $300 commutation fee or send a substitute in their place, as William Elliot did.

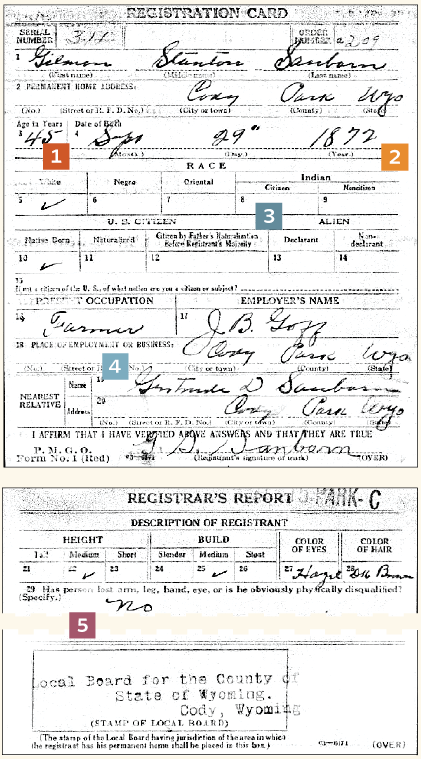

WWI Draft Record

1. At 45 years old, Gilman Stanton Sanborn was at the upper end of the draft range. The Selective Service Act required men age 18 to 45 to register.

2. Draft cards can substitute for early birth records. Gilman was born in 1872. Like many states, Wyoming didn’t begin keeping birth records until the early 1900s.

3. WWI draft cards indicate whether immigrants were naturalized or if not, whether they had declared intention for citizenship.

4. Who was Gertrude D. Sanborn, Gilman’s nearest relative? Draft records often provide evidence of wives, parents or siblings.

5. Each card has two sides. The reverse notes the man’s physical description, with a stamp showing where he registered.

Using Draft Records

Once you’ve found a draft record, you’ll want to get all the information you can from it. What does it tell you about your ancestor? Is this consistent with what you already know about him? There might’ve been many men with similar names in any given state. Analyzing the information is crucial to making sure you’ve found the right one.

Compare facts such as birth date and place with information from census records and death records. The name of a specific town or township of birth is an important detail, giving you a place to dig for other family records. If the draft registration database reveals other men with the same surname born in the same place, you’ll want to investigate a possible kinship between them. Could they be brothers?

Consider his occupation as well. Draft records generally provide more details about employment than census records. You may find the name and address of the company or landowner your ancestor worked for. Exploring this further can provide a lot of interesting material for your family history.

Many draft records asked questions about birthplace and US citizenship. If your ancestor wasn’t born in America, his draft registration might indicate if he’d started or completed the naturalization process. Based on this, you can search for a passenger list, declaration of intention, and/or final papers. Non-citizens who agreed to fight for the United States often received expedited naturalization after the war.

Both WWI and WWII draft records list the name and address of the nearest relative or “person who will always know your address.” Who did your ancestor put down for this? Married men typically named their wives. Unmarried or widowed men might’ve named a parent, sibling, friend or employer. If you don’t recognize the person your ancestor named, try to determine who he or she was. You could discover a relationship you didn’t know about.

It’s particularly interesting to compare the cards of those who registered as young men for World War I and again in the Old Man’s Draft for World War II. These records give you snapshots of your ancestor at two points in time, about 25 years apart. Note the differences in address, employment, nearest relative or contact person and physical traits.

Finding a draft record naturally leads to the question of whether or not an individual actually served in the war he registered for. To determine this, you’ll want to learn more about the records created for that particular war.

Enlistment records, service records, discharge papers, state adjutant generals’ reports, and published unit histories are among the places you might look. Many of these resources are now available online. For an overview, see the United States Military Records wiki on FamilySearch.

You might also find accounts of men who served in a county history book or local newspapers. During the Civil War, newspapers often published notices of enlistments and events. They sometimes published lists of those attending GAR (Grand Army of the Republic) events in later years, or noted an old soldier’s service unit in his obituary. Also search for your potential Civil War ancestor in the 1890 veterans’ census, soldiers’ home records and pension files. Because they usually contain a good deal of documentation, pension records are particularly worth seeking out.

Cemetery records are another way to confirm service, as many veterans’ gravestones bear military inscriptions or markers. Gravestone photographs and memorials on Find A Grave and BillionGraves often indicate military service. Some towns and counties have constructed veterans’ memorials or published lists of those who served in various conflicts.

Military draft registrations served a specific government purpose in times of war. Knowing how and why draft records were created can help you use the information to better understand your ancestors. Draft registrations can provide evidence of birth dates and places, marriages, names of parents or other relatives, addresses, employment, physical appearance, and more. Used in conjunction with other evidence, these details allow you to develop a fuller picture of your ancestor’s life, and pave the way to future discoveries.

Fast Facts

- Record coverage: Civil War, World War I, World War II

- Key details in draft records: name, address, age, date and/or place of birth, race, citizenship status, marital status, employment information, name of nearest relative, physical characteristics

- Find original records at: National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in Washington, DC; NARA branches, and the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis

- Research online at: Ancestry.com, FamilySearch, Findmypast, Fold3

- Search terms: Civil War (or WWI or WWII) plus draft records; US draft registration records

- Associated/substitute records: military enlistment rosters, service records, state adjutant general’s records, military unit histories, military pension records, newspapers, and county histories

Toolkit

Websites

- Ancestry.com: Draft, Enlistment and Service records

- Cyndi’s List: US Military Records

- FamilySearch Wiki: US Military Draft Records

- FamilySearch

- Findmypast.com

- Fold3

- Linkpendium: Click links for the place you’re interested in, then look for a military records section.

- National Archives: Military Records

- National Archives Regional Record Centers

- National Personnel Records Center

- Online Military Indexes & Records

- Selective Service Records

Publications and Resources

- Guide to Genealogical Research in the National Archives of the United States, 3rd Edition, by Anne Bruner Eales and Robert M. Kvasnicka (NARA)

- One Million Men: The Civil War Draft in the North by Eugene Murdock (State Historical Society of Wisconsin)

- Uncle, We Are Ready! Registering America’s Men, 1917-1918 by John J. Newman (Heritage Quest)

- US Military Records by James C. Neagles (Ancestry)

Versions of this article appeared in the July/August 2015 and January/February 2023 issues of Family Tree Magazine.