Have you heard stories about a Revolutionary War or Civil War soldier in your family, but lack documents about him? Or maybe you don’t have stories, but you wonder about your military heritage. Military service in the 18th or 19th century can be an important part of your family’s story. Yet how do you determine whether an ancestor served in a war, if any records of his service exist, and where to find them?

Fortunately, the US government realized long ago that it needed a way to keep track of an individual’s service—especially when it came time to pay veterans benefits. The resulting compiled military service records, or CMSRs, offer a window of opportunity to genealogists looking for information about men who served in wars prior to 1902.

Keep reading to learn how you might find a CMSR. Note that service during more-recent conflicts—World War I to the present—was documented differently. Records are generally held by the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, and many were destroyed by a fire in 1973.

What’s a CMSR?

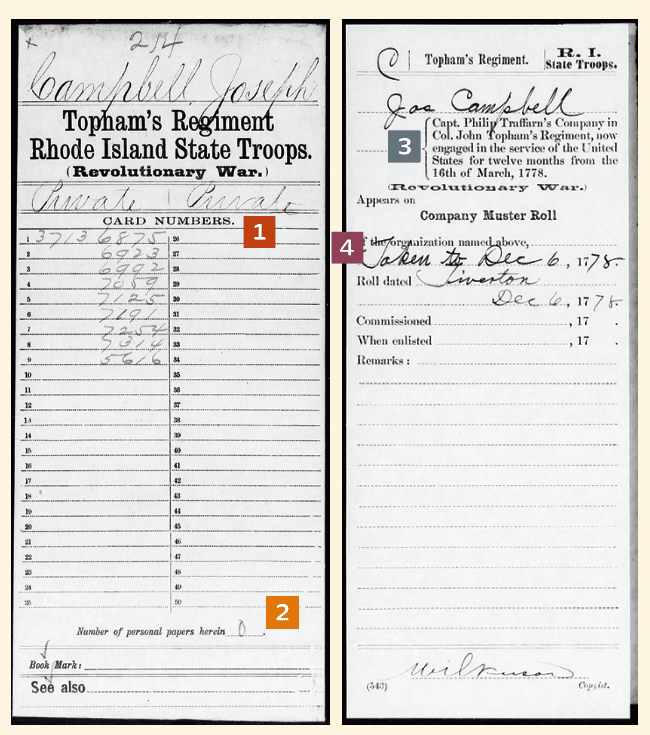

A CMSR is an envelope (called a jacket) containing a set of cards that provide an overview of an individual’s service in a military company. The jacket is labeled with the soldier’s name, rank, military unit and a list of card numbers. The information on each card was taken from some type of original record in which the soldier’s name appears, such as an enlistment book, muster roll, hospital roll, descriptive book, prison record, payment voucher or discharge. Some CMSRs, especially those of officers, also may contain personal papers.

In the aftermath of the Civil War, clerks of the War Department Record and Pension Office painstakingly copied information from original records onto the cards to expedite the processing of pension claims. Rather than sift through more than 500,000 rolls and books to verify a man’s service, pension officials could now find what they needed in minutes. Family historians reap the same benefits today.

Once the Pension Office completed Union Civil War CMSRs, clerks did the same thing for men who’d served in the Revolutionary War, War of 1812, 19th-century Indian wars and Mexican-American War. Service records for Confederate soldiers, the Spanish-American War, and the Philippine Insurrection were created a bit later. By the time the CMSR record-keeping system was discontinued before World War I, clerks had created about 58 million cards.

CMSRs primarily cover those who served in volunteer military units, typically raised at the local or state level in times of war. With the exception of the Revolutionary War, few CMSRs exist for men who served in the regular Army (career soldiers). Civil War “volunteers” included men who were drafted as well as those who enlisted voluntarily. If your ancestor re-enlisted or served in two different companies during a war, he’ll probably have two separate CMSRs.

How trustworthy are CMSRs? Though derivative sources, CMSRs have highly reliable information. Accuracy was vital to the government officials who transcribed the data in them, so the original rolls rarely contain more information than was copied into the CMSR.

Clues in a CMSR

The number and type of cards included in a CMSR varies from war to war and soldier to soldier. Civil War and later folders tend to be more robust than those from earlier wars.

In addition to the soldier’s rank and military unit, you might discover some or all of the following in a CMSR:

- date and place he enlisted

- age at enlistment

- place of birth

- physical description

- occupation

- term of enlistment

- date and location he mustered into (joined) the unit

- name of his commanding officer

- his presence at regular musters

- notations about illness, wounds or desertion

- date he mustered out (left) the company or died

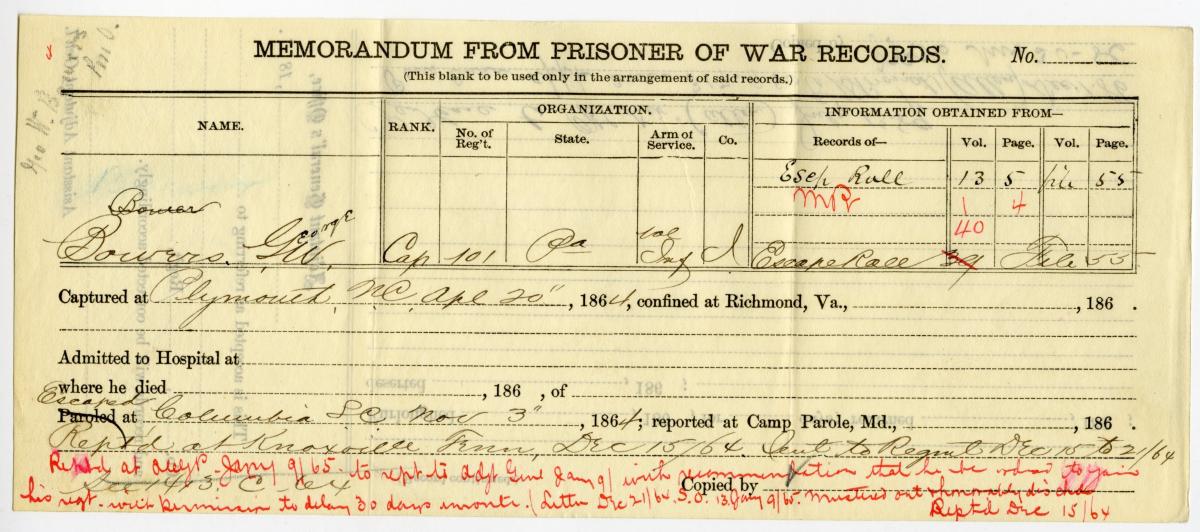

These bits of data can tell you a good deal about your ancestor’s wartime experiences. You might find he stayed in a field hospital due to illness, or learn when he was wounded. If a man was captured by the enemy, deserted or died while in service, his file should have a reference to it. Any personal papers (documents that pertain to only one individual) tucked into the jacket will give you even more details. While service records don’t generally name a soldier’s parents, you may find hints to help in your search for their identities.

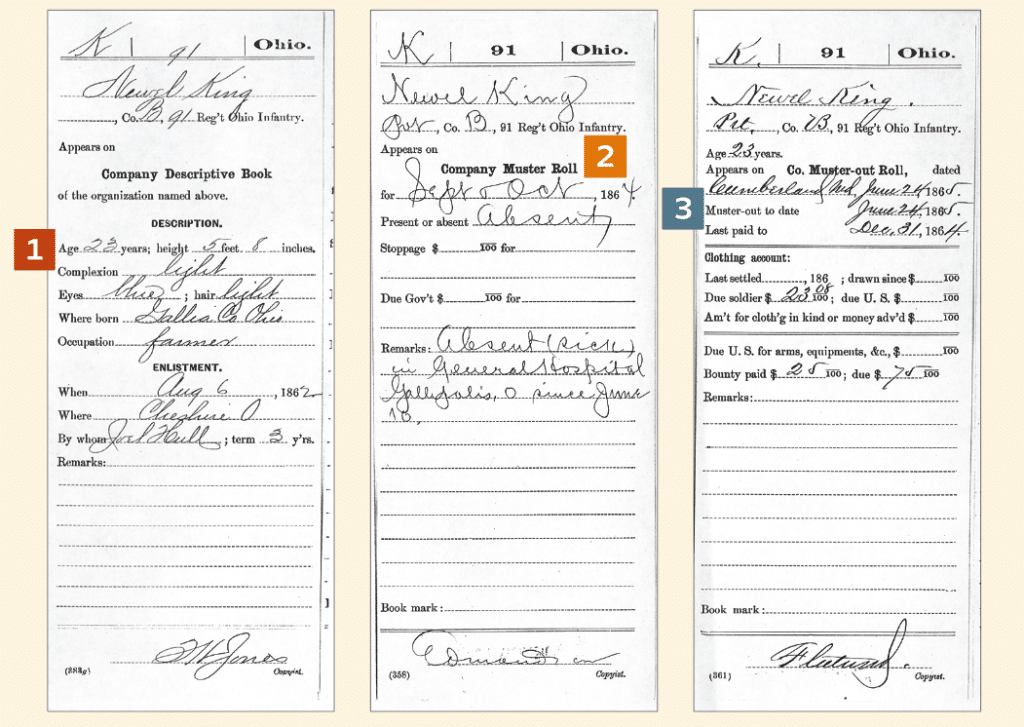

One note about age: A man’s age when he enlisted remained his age in military records created throughout his term of enlistment. This gets confusing when you see someone was 23 years old when he joined up, and was still 23 when he was discharged two or three years later. Using a consistent age gave the army another means of identifying a particular man—a tactic you can use to your advantage as well.

Finding CMSRs

Depending on the war, your soldier’s CMSR may be on microfilm and/or digitized online. If it’s not online, you’ll need to look up the name in a service records index, then find the record on microfilm or order a copy from NARA (we’ll tell you how in a few minutes). Start with these steps:

Revolutionary War (1775–1783)

A century after the war ended, service records were compiled for men who served in the Continental Army, various state and local militia units, and the American naval forces. There’s good and bad news for researchers hunting for ancestors who served in this war. The bad news is that many records were destroyed when the British burned Washington, D.C., in 1814, and others deteriorated or were lost over the years, so not every man who served has a CMSR. The good news is that all the surviving records have been indexed, microfilmed, and digitized.

You can search the complete collection on Fold3. This contains actual images of soldiers’ service record jackets and cards, digitized from NARA microfilm. A similar collection provides the same access to sailors. For best results, be flexible with name spellings, and try using an asterisk (*) to substitute for one or more letters in question.

War of 1812 (1812–1815)

During this war, many men enlisted in local or state militias for short stints (three to nine months), and some served in more than one company. The resulting CMSRs are generally thin, sometimes holding only a few cards. They’re fascinating nonetheless.

Get started with the full index to War of 1812 service records, derived from NARA microfilm number M602, on Ancestry.com. The index includes name, rank, company or regiment, and “roll box” where the CMSR is located at the National Archives.

The CMSRs themselves for this war haven’t been microfilmed or digitized. Use the information from the index to order a copy of your ancestor’s file from NARA.

Indian Wars and Mexican-American War (1816–1858)

With the frontier expanding rapidly, skirmishes erupted between settlers and native Indian tribes in several areas. Volunteer armies were raised for the Seminole Wars, Black Hawk War, Creek Wars and other conflicts. Fold3 has digitized the index to service records for these military engagements (from NARA M694). Order his service record from the National Archives.

Fold3 (and FamilySearch) has also digitized an index to Mexican-American War service records (from NARA M616). In addition, Fold3, Ancestry.com and FamilySearch have full CMSRs for just a handful of states; you’ll need to request records from other states from NARA.

Civil War (1861–1865)

Civil War service files generally contain more information than those from earlier wars. You might see a long list of numbers on your ancestor’s file jacket. Those numbers don’t mean anything in research terms, but do indicate there’s a lot of good stuff inside. Types of cards you’ll commonly find include:

- Company muster-in or muster-out rolls that identify rank, age, date and place of enlistment, term of enlistment, date and place of mustering in/out, date last paid, and balance owed or due

- Company descriptive books that give enlistment information; color of eyes, hair and complexion; birthplace and occupation

- Company muster rolls that tell whether the soldier was present for the period of time specified on the card (generally two months), along with any remarks

Union Civil War CMSRs are indexed by state, and the files for several states have been microfilmed and/or digitized. All Confederate CMSRs have been digitized.

Whether your ancestor hailed from the North or the South, start with Fold3. Browse by the state where your relative lived at enlistment. Enter the name in the search box, using a middle initial if necessary to narrow the results. If the file is digitized, you’ll be able to download it. If only the index card in available, order the file from the National Archives.

Spanish-American and Philippine Wars (1898–1902)

Service records for men in these two brief conflicts were created similarly to Civil War CMSRs. A card index for men who served in the Spanish-American War in 1898 is on microfilm (NARA M871) and online. You’ll find it at FamilySearch as the United States Index to Service Records, War with Spain, 1898, at Fold3, and for free at MyHeritage. Unless your ancestor hailed from Florida, you’ll need to order a copy of his file from NARA. Digital images of Florida Spanish-American War CMSRs are on Fold3.

The Philippine Insurrection developed in the wake of the Spanish-American War and lasted until 1902. The index to these service records, NARA M872, is available as part of a larger collection at FamilySearch, but the records themselves are not. If you think your ancestor served in the Philippines, consider making a trip to the National Archives or hiring a professional researcher.

Ordering a CMSR

All these pre-WWI service records are now held at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in Washington, DC.

NARA has an online order form you can use to request a copy of your ancestor’s CMSR from any of the wars listed here. Go to archives.gov/forms and scroll down to “(Pre-WWI) Military Service Records (NATF Form 86).” Select whether you want to order online or mail in the form. You can receive the file electronically as a PDF emailed to you, or in print via postal mail (all for a fee). Orders are estimated to take two or three months to fulfill, though wait times at many archives have been longer due to back-orders associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.

If you don’t want to wait that long, you have a complex request, or you don’t know exactly which file you need, consider hiring a professional genealogist in the Washington, D.C., area. He or she may be able to get records faster or determine which of two George Smiths is your ancestor. You can find a researcher through the Association of Professional Genealogists or the Board for Certification of Genealogists.

Then again, perhaps you want to visit NARA to retrieve your ancestor’s file in person. Plan ahead for your trip using the resources at archives.gov/research. You must schedule an appointment to access research rooms.

Using CMSRs and Indexes

Indexes to service records often show more than one man of the same name from the same state. Particularly if the name is common, it can be a challenge to determine which one is your ancestor. First identify the veteran in pension records, which also name military unit, wives or other family members. Those details might help you identify the right serviceman.

Compare details in a service record index with your other genealogical information. Does his age in the CMSR correspond with his age in censuses? What about his location? Men typically joined units that formed close to home, often with neighbors. To find the names of units raised in a county, check local histories and consolidated state lists. A web search on the company name or number also can help you find out where its members lived.

Once you’ve obtained the right CMSR, squeeze every detail out of it. Begin by sorting the cards in rough chronological order: first the muster-in roll and descriptive book cards, then the muster cards in order, followed by the muster-out card. Transcribe the information into a word document or spreadsheet to get an overview of your soldier’s service.

Then look for clues to other documents. A place of birth and age at time of enlistment can lead you to a birth year, which you can use to find related census, church, probate and land records. Those might give you the names of possible parents and other relatives.

To research your ancestor’s wartime experiences more deeply, find published histories of the regiment or company he served in. WorldCat can help you find books in libraries.

Learning about your ancestor’s military service is exciting and enlightening. With the availability of online indexes and databases, it’s easier than ever to find this piece of your family history puzzle.

Fast Facts: Compiled Military Service Records

- Coverage: Pre-World War I military conflicts, with notes about service dating to 1775

- Jurisdiction where kept: US War Department, maintained by the National Archives

- Key details: Soldier’s name, age, rank, military unit, dates and places of enlistment and musters, date and place of discharge, sometimes place of birth, physical description

- Alternates and substitutes: Draft records, pension records, lineage society applications, bounty land grants, military payrolls and ledgers, soldiers’ home records, 1890 special census of Civil War veterans and widows

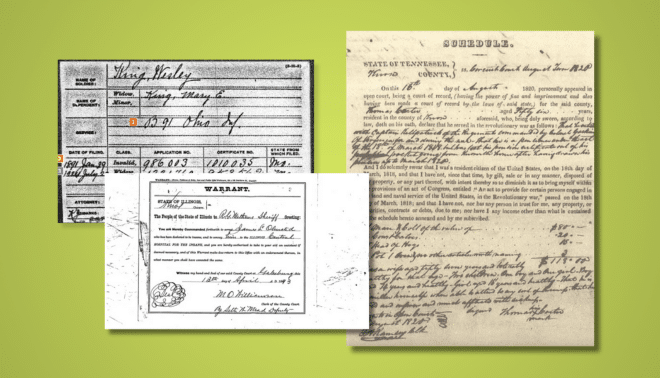

Sample Records

Revolutionary War CMSR

- The jacket of Joseph Campbell’s CMSR identifies the unit he served in and his rank of private when he entered and left. The card numbers aren’t significant, but do indicate nine cards are inside.

- No personal papers are in this file. Files of officers are more likely to contain additional papers, such as enlistment forms or casualty reports.

- This muster roll card shows the company formed 16 March 1778, and the term of service was 12 months. We might learn more about Joseph’s experiences by researching his officers.

- Joseph was present at the muster roll taken 6 December 1778, in Tiverton, RI. Researching place names can also shed light on wartime events.

Civil War CMSR

- The Company Descriptive Book section of Newel King’s CMSR shows he was 23 when he enlisted 6 August 1862. This gives an approximate birth year of 1839. The card also states his place of birth: Gallia County, Ohio. These clues could lead to his parents’ names.

- The jacket contains several company muster roll cards. This one, for September and October 1864, reports Newel was absent from the company because he’d been hospitalized for illness.

- The company muster-out roll shows Newel was discharged 24 June 1865 in Cumberland, Md. Note that his age was still 23 years; the military used the same age throughout a man’s term of service as a means of identification.

Military Service Records Resources

Websites

- Ancestry.com: Military Records

- Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Database

- Cyndi’s List: US Military Records

- FamilySearch Wiki: US Military Service Records

- FamilySearch: US Military Records Collections

- Findmypast

- Fold3

- MyHeritage: Military Records

- National Archives: Military Records Research

- Online Military Databases and Records

Publications

- Genealogical Resources of the Civil War Era: Online and Published Military or Civilian Name Lists, 1861-1869, and Post-War Veteran Lists by William Dollarhide (Family Roots Publishing)

- Guide to Genealogical Research in the National Archives of the United States, 3rd Ed., by Anne Eales and Robert Kvasnicka (NARA)

- Index to Revolutionary War Service Records by Virgil D. White (National Historical Publishing)

- Military Service Records at the National Archives by Trevor Plante (NARA)

- Military Service Records: A Select Catalog of Microfilm Publications (NARA)

- US Military Records: A Guide to Federal & State Sources, Colonial America to the Present by James Neagles (Ancestry, Inc.)

Tip: If you find a date your ancestor was wounded or captured, look for a history of the war to see what battle or skirmish the date corresponds to.

Tip: Look for a company raised in the county where your ancestor lived in the 1860 census to help you select which Civil War CMSR to order.

Related Reads

Versions of this article appeared in the May/June 2016 and July/August 2023 issues of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: May 2025