When General Douglas MacArthur gave his famous farewell address to Congress in 1951, he quoted a refrain from an old Army barracks ballad: “Old soldiers never die, they just fade away.”

From the earliest days of the United States, millions of young men and women have stepped forward to answer their country’s call to arms. It’s rare to find a family that can’t lay claim to at least one veteran, but unfortunately for the family historian, only a small percentage of those millions ever reached the icon status of men like MacArthur, George Washington, Ulysses Grant and Robert E. Lee.

For the rest of us, the reality is that our old—and young—soldiers, sailors, Marines and airmen do die, and they have an uncanny knack for taking the details of their service with them. We’re left with a faded history detailing name, rank and serial number.

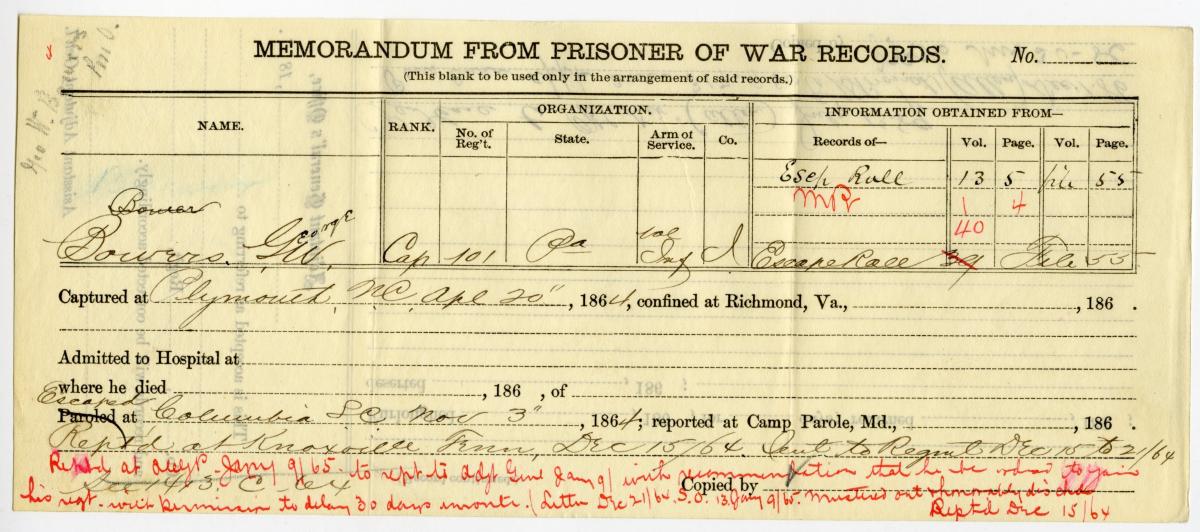

If you’ve already slogged through all the compiled service records, pension files, muster rolls and special census records that you can stand, here are some ways to bring your family’s military heritage back to life.

1. Start at Home

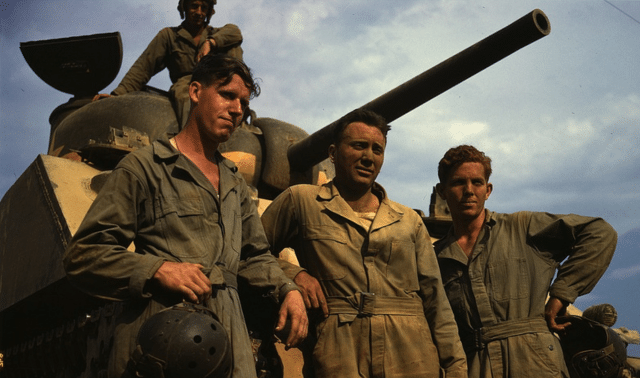

A close friend, a veteran of the 305th Bombardment Group, likes to repeatedly remind me that World War II veterans are passing on at a rate of 1,200 a day. Whether they served in World War I or in the Gulf War, the message here, of course, is to start with your family’s living veterans.

If they’re hesitant to talk about their experiences, ask if they’ll write about it. Enlist the help of other family members and even other veterans. Start with the easy questions first—ask about training, barracks life, non-combatant duties and what they did while on pass or leave away from their ship or post.

Don’t be put off by family members who refuse to discuss the details of combat. Instead, focus on establishing their presence at specific locations on specific dates—you can always use other sources to fill in the blanks.

Gather and photocopy or scan any photos, promotion orders, movement orders, identification cards or tags, performance reports, citations and awards, pilot log books, draft cards, ration books, medical records and discharge papers. Photograph ribbons and medals, old uniforms, and war trophies or souvenirs.

Don’t forget to interview spouses or children about their experiences. Their stories about Victory Gardens, scrap drives, war bonds, military life, sad goodbyes and tearful homecomings will round out your story.

2. Research the Unit(s)

Once again, people are your best source of information. Thanks to popular movies such as Saving Private Ryan, Gettysburg and Pearl Harbor, a whole new generation of Americans is getting interested in the country’s military history. That’s making it easier than ever to find veterans who are willing to talk—or who’ve already published their memoirs.

Military-specific bulletin boards and mailing lists such as those found at RootsWeb, Military.com and Cyndi’s List are great places to start your search for veterans. Next, use search engines such as Google to locate personal and unit association websites that may be hidden away in the digital world.

But no matter how many websites you find and people you contact, finding someone who knew your ancestor personally can still be difficult, if not impossible. If that’s the case, focus instead on contacting people from the same unit and adding general information about the unit and its operations to your history.

If you can’t find people from the same unit, look for members from similar units who served in the same area, people who enlisted from the same area, served at the same bases, flew the same type of plane, or spent time in the same prisoner-of-war camp.

Make sure you ask about unofficial unit histories, yearbooks and cruise books. These books typically include photos of every member in the unit, details about deployments and training, firsthand accounts of combat actions, and memorials for those who didn’t return.

Some of these items may be available through rare book dealers or at university libraries—especially ones located near military bases. Consider subscribing to unit association newsletters (usually for a nominal fee) and attending reunions (ask for permission first).

Many of them publish or post firsthand accounts, original combat reports and official unit histories. Newspaper articles, diaries and local histories published at or near old battlefields, towns where units were formed and old outposts may also provide additional gems.

Living history units are also great sources of accurate information about America’s older wars. Re-enactors spend countless hours—and a lot of money—researching even the most mundane details about uniforms, equipment, tactics, battles and camp life.

If you want to know what kind of comb a member of the First West Virginia Cavalry might have carried into battle, ask a living historian. Many units maintain their own websites and will respond to email queries.

As with any research, make sure you record contact information for anyone you interview.

3. Add Photographs, Maps and Supporting Documents

Copies of photos, maps, newspaper articles, letters and speeches of community and political leaders, diary entries, and even old recruiting posters are widely available on the internet and in antiquarian bookstores.

These tidbits may shed some light on why your ancestor marched (or didn’t march) off to war or joined a popular uprising against a state legislature.

4. Sign Up for a Hitch

Well, not really, but you should take to time to explore today’s US Armed Forces. Many of the military’s websites offer a ton of information and freebies such as royalty-free photographs, fact sheets, news articles and clip art images depicting everything from tanks to rank insignia.

The sites also contain links to military installations around the world, and you’ll find that many of them are the same bases where your family members served. If you’re lucky enough to have a base in your backyard, or are planning a trip near an important installation, call the public affairs office there and see if tours are offered.

Don’t overlook the services’ historical agencies either. They offer a wealth of information and may be able to help you over some of those pesky brick walls.

5. Honor Your Family’s Service

On a recent trip to the battlefield at Gettysburg, I realized the possibilities for honoring a family’s military service were limited only by imagination. A seemingly endless array of authentic and replica militaria—uniform items, non-firing weapons, military art, cased flags—is available from every period of our country’s past and just waiting to be put to use by a creative mind.

There’s a replica saber for that ancestor who served in the Confederate cavalry, a bugle for that Buffalo Soldier, a fife for the Minuteman, and a bayonet for that World War I doughboy. Add one of these wonderful items to a plaque with a brass nameplate and all of a sudden, those basic details—name, rank, dates of service—take on a completely new form.

Of course, you’ll want to change it up a bit, so consider a fairly recent military tradition—the shadow box. Normally presented at retirement ceremonies, these display cases include mementos of a person’s service. Medals, ribbons, rank insignia, unit patches, qualification badges, unit coins and service seals are typical items you’ll find in a shadow box. Whether your veteran served in the American Revolution or the Gulf War, the Army or the Coast Guard, the vast array of items available for historical re-enactors should make assembling one of these displays fairly easy.

As a bonus, you might even be able to request actual replacement medals and decorations for your family’s veterans. Check the National Archives and Records Administration website for information about this program and the Cold War recognition certificate program.

Not only will completing your “wall of honor” take your family history efforts to new heights, it’ll serve as a visual reminder to all who see it that freedom really isn’t free. As our first commander in chief, George Washington, once observed, “The willingness with which our young people are willing to serve in any war, no matter how justified, shall be directly proportional as to how they perceive the veterans of earlier wars were Treated and Appreciated by their Nation.”

Related Reads

A version of this article appeared in the April 2002 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: June 2024