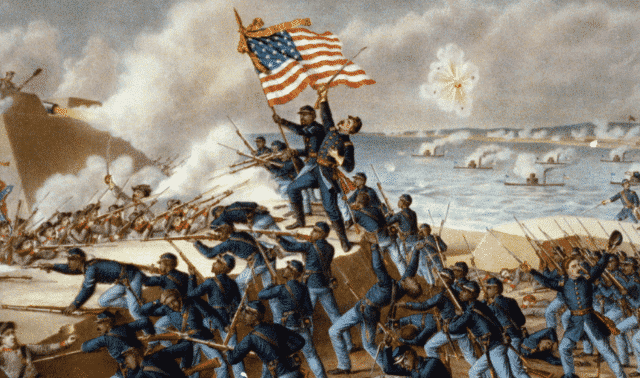

This year the nation marks the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, which lasted three bloody days starting July 1, 1863.

Emboldened by his success at Virginia’s Chancellorsville that May, Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee embarked on his second and most ambitious invasion of the North. Lee hoped to shift the battleground of the war from northern Virginia to Pennsylvania, striking at the capital in Harrisburg and even Philadelphia, and force the Union to the negotiating table.

At Gettysburg, Lee faced Union Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade, who was given command of the Army of the Potomac only three days earlier when Lincoln relieved Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker of his command. On the third day of fighting, Union troops repulsed a dramatic infantry assault by 12,500 Confederates—Pickett’s Charge—against the center of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge. After this “High Water Mark of the Rebellion,” Lee retreated to Virginia and the Confederate cause was doomed.

The battle involved some 94,000 Union and 72,000 Confederate soldiers. Casualties would number about 23,000 on each side, with nearly 8,000 killed between the two armies. Months later on Nov. 19, President Lincoln eloquently dedicated a national cemetery on the site with his famous Gettysburg Address.

Were any of your relatives among those astounding numbers on either side—or perhaps on both sides, fighting against each other? Because Gettysburg is one of the best-known and most-documented battles of the Civil War, it’s not hard to find out, even 150 years later. Not only can you discover the bare facts of your ancestor’s service with these seven steps, but you also can explore what their military units did during those fateful three days in July. Let’s get started.

1. Search the Civil War Soldiers and Sailors System.

This site www.nps.gov/civilwar/soldiers-and-sailors-database.htm, created by the National Park Service, lets you search for basic information on 6.3 million military men from both sides, representing 44 states and territories. Once you find an individual, you can click from his record to that of his regiment and then to accounts of Civil War battles the regiment fought in. Keep in mind, however, that just because your ancestor was part of a regiment that was fought at Gettysburg doesn’t necessarily mean he was with the regiment at that time: He could have left the regiment (or been wounded or killed) prior to July 1863, or joined it after Gettysburg.

Searching the database of names is simple—just plug in what you know about an ancestor, such as name and state he might have served from, and choose Union or Confederate. A search for Andrew Osgood from Vermont, for example, quickly turns up a Pvt. Andrew E. Osgood in Company H of the 13th Regiment, Vermont Infantry.

Sometimes, however, you need to leave out some details to find your man. Searching for a Confederate ancestor, Charles W. Burrows (or Burrow) from North Carolina, initially draws a blank. But searching for any Burrows from North Carolina finds “W. Burrows” of the 6th Regiment—alternate name “Charles W. Burrow.”

Keep in mind that you may find multiple entries for the same man if he served under variant names or in multiple regiments. It’s also common to find multiple soldiers of the same name in the database. Use what you know about your soldier—his age at enlistment, where he enlisted from, etc.—to rule out nonrelatives.

2. Read up on the regiment.

Did either Pvt. Osgood or Pvt. Burrows see action at Gettysburg? Click on the link for each man’s regiment for brief regimental histories (which also include links to complete lists of soldiers in each unit). Indeed, both units were present at Gettysburg, and the notes for the the North Carolina unit state, “Of the 509 engaged at Gettysburg, 36 percent were disabled.”

3. Check the monuments.

More so than any other battle of the Civil War, Gettysburg is commemorated by statuary and other monuments—more than a thousand in all. You can take a photographic tour at Draw the Sword, which also has entries for monuments to individual units that fought there. At the page for the 13th Vermont, whose monument was dedicated on Oct. 19, 1899, you also can see secondary markers for the unit’s positions during the battle, one of which indicates that the 13th helped repel Pickett’s Charge. It was part of Stannard’s Brigade in Doubleday’s Division of the First Corps—that’s Abner Doubleday, popularly credited with inventing the game of baseball.

Scrolling down, you’ll find a list of officers killed at Gettysburg and soldiers buried in the Vermont Plot of the Gettysburg National Cemetery—among them, Pvt. Andrew E. Osgood, Company H. You can also click for a detailed “after action report” by Col. Francis V. Randall, describing the unit’s role in the battle in detail.

Plaques, rather than full-blown monuments, often commemorate Confederate units at Gettysburg, and so information at Draw the Sword is sketchier. To find facts about a unit using the dropdown menu, you’ll need to know the commanding officer of the brigade (in this case, Hoke) and the regiment it belonged to. Or do a Google search for the unit plus site.

Another, similar site is Stone Sentinels, which has links to the handful of unit-specific Confederate monuments.

4. Consult the Official Record.

At CivilWar.com, you can search or browse the “OR,” the Official Record of the war written by the officers and commanders who fought it. Not surprisingly, the account of Gettysburg fills three volumes, some 3,000 pages in all. Searching the site can be awkward, though. Your best bet to see if a Gettysburg ancestor is mentioned is to search by last name, then browse the results for entries from volume XXVII. You also can search or browse the OR at eHistory and The Making of America. At the latter, you can individually search the three parts of the volume that includes Gettysburg, and use operators such as AND to narrow your search.

5. Google the regiment.

America’s fascination with the Civil War has led to a wealth of histories and other data on individual regiments, many of which are now online. For example, you can read more about the 13th Vermont in pages at Vermont in the Civil War, the Civil War in the East and the Civil War Librarian. The Vermont Historical Society has letters from the state’s soldiers, including some from the 13th. Google Books also turns up a title called Brigades of Gettysburg in which you can search for specific units.

Googling the 6th North Carolina Regiment leads to a detailed roster and man-by-man writeup of the “Cedar Fork Rifles,” Company I, a history of how the state’s Civil War regiments formed and even the diary of Bertlett Yancey Malone, a member of the regiment.

A Google search for “Gettysburg casualty list names” or “6th NC Gettysburg” returns the evidence we’ve been looking for that Charles W. Burrow not only was a member of the regiment but also fought at Gettysburg. A Rootsweb page has transcribed a casualty list from the National Archives (M836-3) for the 6th North Carolina Regiment in the Battle of Gettysburg. There we find: “Burrows, Chas. W., Prvt., Wounded, Thigh, Slight, 7/2/63.”

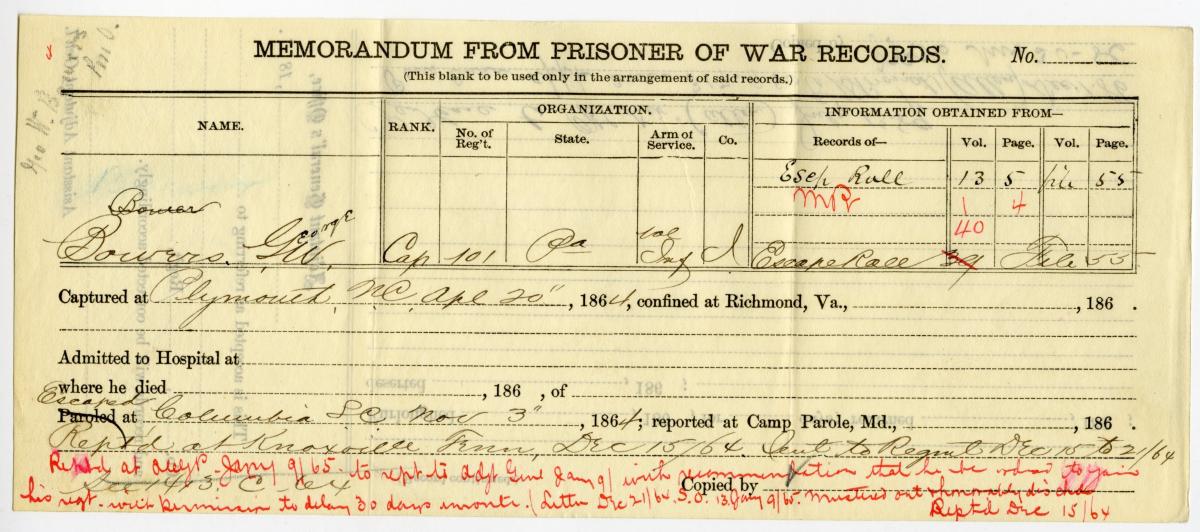

6. Search Fold3.

Subscription military records site Fold3 has been digitizing records of the National Archives. Confederate service records are more fully represented than those of Union soldiers, and just a few clicks takes us to 21 scanned pages of Charles W. Burrow’s file. These include muster rolls, details of his enlistment in Charlotte May 28, 1861, as a volunteer, and this entry: “Taken prisoner at Chancellorsville. Supposed to have been killed in battle at Gettysburg July 2, 1863.” He also appears as wounded on “a list of those killed, wounded or missing” among Early’s division in the Gettysburg campaign.

Vermonter Andrew Osgood’s Fold3 service records are skimpier—a single index card confirming he was in the 13th. Here you also can check a card index to Civil War pension records; a card confirms his service, as Osgood’s father filed in 1880.

7. Try the National Archives.

Spoiled as we are by having so much military history at our fingertips online, sometimes we have to turn to old-fashioned paper records to complete the picture. Most Union compiled service records (CSRs) still require ordering from the National Archives and Records Administration. You can, however, at least go online to order these and other pre-1917 records, at Archives.gov.

We already know, of course, what became of Andrew Osgood, who died at the Battle of Gettysburg, but his service records might provide some additional details as well as information about his pre-Gettysburg service. We also can turn to the Nationwide Gravesite Locator to more specifically locate his burial site at Gettysburg (Vermont section, site 20) and find his date of death (July 7, shortly after the battle ended). Find A Grave even has a photo of his marker.

The fate of Charles W. Burrow remains elusive. Did he recover from that “slight” thigh wound received on the Gettysburg battlefield? His file contains no more muster rolls beyond the one that would have included Gettysburg (May 12-Aug. 31, 1863), so it seems likely that his wound—or a subsequent infection—did cost him his life.

We do know, from the Soldiers and Sailors website, what became of Charles’ regiment after suffering such a horrendous casualty rate at Gettysburg: “At the Rappahannock River in November, 1863, it lost 5 killed, 15 wounded, and 317 missing, and there were 6 killed and 29 wounded at Plymouth. It surrendered with 6 officers and 175 men of which 72 were armed.”

More Online

• Tools for “traveling” to your ancestors’ era

• Common abbreviations in military records

• Finding Civil War sailors

• Using Civil War muster cards download

• Civil War Research Family Tree University online course

• What’s in a Civil War Pension File? video class