Jump to:

Railroad

Mining

Automotive

Other Industries

Resources

“So what do you do for a living?”

It’s a common get-to-know you question in the United States. What people do for half (or more) of their waking hours tells a lot about them. You can guess at their interests, skills, values, educational background, and—when the job is tough—their endurance.

Our ancestors’ vocations offer unparalleled insight into their everyday lives, too, especially if they worked in industry. Their job descriptions can tell you which muscles ached most at the end of the day; what mortal perils they faced on the job; and what their living conditions and neighborhoods were like. Their work tells you something about the determination—sometimes desperation—that drove them back to the dark mineshafts, loud production lines, or glowing furnace fires each day.

Their industrial labor also generated heavy-duty paperwork. You’ll find similar types of documents and historical ephemera across different industries—here, we’ll focus on the worlds of railway, mining, and auto workers.

Railroad

For nearly a century, railways were the major mover of people and goods in the United States. The first passenger railway (Baltimore & Ohio, or B&O) opened for business in 1830; transcontinental service was available by 1869. Not until well into the 20th century did automobile travel and truck transport significantly affect travel by rail. Railroads employed workers all along their tracks, from track layers to locomotive repairmen to conductors to stationmasters.

After 1936, the Railroad Retirement Board began administering retirement benefits to railway workers and their families. For a fee, you can request records on deceased employees (since 1936). As of late 2010, some genealogical requests will be referred to the National Archives and Records Administration, but you should still begin your request with the Railroad Retirement Board.

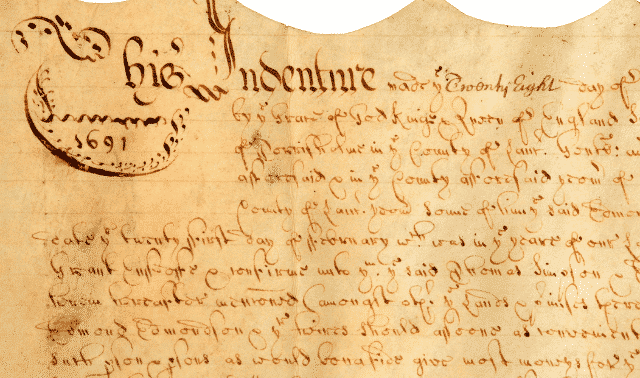

Although pre-1936 employee records are difficult to find, various archives and historical societies have rescued and preserved some over the years. Records can include employment applications, personnel files with job classifications and payment information, employee rosters and pension paperwork. Find insurance records for Pennsylvania Railroad employees dating back to 1865 at the Pennsylvania State Archives. The California State Railroad Museum has 50,000 employee record cards (1900 to 1930) for the Southern Pacific Railroad with birth dates, addresses, and job and wage information.

Locating records

How can you find these records for your ancestor? The trick lies in figuring out which railroad your ancestor worked for. A few genealogy resources to check first:

- County histories

- Newspapers

- City directories

Once you have the name of the railroad, you can do some general searches to find out more about what records might exist today that will reveal more about your family history when it comes to this popular occupation.

Paula Stuart-Warren has some tips for finding those relevant railroad records in this short video.

If you know where your ancestor lived, search directories for locations that house these records. Start with Sponholz’ directory Locations of Railroad Genealogical Materials. Also check out the Railroad Retirement Board’s list of links. Contact local and state historical societies. Search the internet with terms such as the company name plus archives or records. See if that company was absorbed into another railway (check the Family Tree of North American Railroads).

Union records are less useful for genealogical research, as it’s hard to find data on individual members. Look to your family shoebox or files for copies of a union card so you can target your search to that union. “Every job classification had a union: The Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen, Order of Railroad Conductors, etc.,” explains Sponholz. His directory includes names of known union record collections.

Both companies and unions published magazines and newsletters, which can be a fantastic resource. “It’s amazing what you’ll find in those things,” Sponholz says. “They really celebrated the lives of employees through these magazines. Births, deaths, promotions: a wide variety of things that affected a person’s life, stuff I haven’t seen anywhere else.”

Employee benefits reports, work-related accident reports, and member profiles show up, too. Check Sponholz’s directory first for magazines, then call around to regional historical and railway societies or search online (a search on Chesapeake Ohio employee magazine brings up a complete magazine collection at the Chesapeake and Ohio Historical Society).

Rarely indexed, magazines usually require old-fashioned page-turning. Check Google Books periodically to see if issues have been posted (Sponholz has found issues of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers magazine there, text-searchable and free). Even if your ancestors aren’t named in the issues you find, you’ll learn a lot about their lifestyles and the issues that concerned workers.

Learning about job duties

Want to learn more about their actual job duties? Sponholz likes the historical section of the Union Pacific Railroad website, with past and present job descriptions. “It’s nice to know the job duties of an ancestor,” he says. “Was he a brakeman in the 1890s? That was one of the most hazardous jobs around at the time. They always said you could tell who the brakemen were: the guys missing a finger or more. What was going through his mind when he got up every morning to go to work?” Sponholz researches accidents in local newspapers and investigation reports (in the ICC Historical Railroad Investigation Reports, 1911-1994, by the Department of Transportation database, and in state historical societies, for state investigations).

Don’t neglect railroad museums across the country for what they can teach you about daily life and work on the railway. Often their staff are railroad buffs who are happy to answer questions. The National Railroad Museum even has an oral history collection and a rail archive with many of the kinds of materials mentioned above. Check with state tourism bureaus for rail museums near you (or near your ancestor’s hometown). For a fun virtual guide to railroading life, chug over to W&H Railroad Document Archives.

Though at present you may have to dig to find railroading relatives, Sponholz is optimistic about opportunities for future research. “I am surprised every year at the stuff that pops up on the internet. Often a new archive has posted holdings or indexed records, or has records online to check. It’s amazing what people are doing with their collections now.”

Mining

At the height of the coal industry in the United States, nearly a million miners of every ethnicity worked the black seams from Appalachia to Washington State. Their colorful yet often grim stories are told today in all kinds of historical publications and collections.

Tim Pinnick, a genealogist and author of the book Conducting Coal Miner Research, generally starts his research in state coal mining reports. “These are probably the most exciting, most available resource specific to coal mining.”

These documents offer “incredible lists of names, not necessarily employee rosters, but rosters that fit particular criteria, like those who were injured or killed in the mines,” says Pinnick. “You can find the names of the companies they worked for, and read testimony of living, breathing coal miners talking about accidents or explosions. This is a great substitute for company records, which tended to be destroyed.” He finds old reports at Internet Archive (search for coal mine report, the state name and the year).

Union newsletters

Next on Pinnick’s list is union newsletters. “Labor newspapers really were the voice of the worker,” he says. The newspapers celebrated the mining community and shared their perspective with a general public that wasn’t always sympathetic to their cause.

Surprisingly, you’ll find plenty of everyday small-town talk even in national union newsletters. “The largest coal mining newspaper, United Mine Worker Journal, tended to cover anyone who sent stuff in, out of the thousands of locals across the country,” says Pinnick. “You’ll find all kinds of genealogical information you would not have expected: obituaries, marriages, wedding anniversaries, or a family with four generations of coal miners.” A column on “resolutions and respects” paid tribute to deceased miners.

One of Pinnick’s favorite features in labor newspapers is the Info Wanted section, where you’ll find notices from people looking for relatives or friends. “It was in the nature of miners to move from place to place, so you tend to lose track of them,” he says. “Sometimes there’s a physical description, last known location, and nicknames. If you’re trying to locate a union miner, the one thing those who know them will all read is the United Mine Worker Journal.”

Find back issues of the United Mine Worker Journal through university libraries (have a good reference librarian help you acquire them through interlibrary loan). Also look for any local or regional mining papers (Chronicling America has at least five such titles on its site; you can select various trades from the Labor Press dropdown menu on the US Newspaper Directory search form).

Oral history

Pinnick also mines oral histories for their unique stories and up-close perspectives, whether the voices are those of ancestors or their co-workers. “I’ve rarely found an oral history that doesn’t go into the lives of other people, and what they [all] did in their occupation. You’ll find info about that individual and the people who make up the community.” Pinnick comes across oral history collections in almost every major mining collection, including those of the State Historical Society of Iowa and the University of Illinois at Springfield.

Immigrant miners can also be researched from the ethnic angle. Coal miners came in every nationality: Italian, British Isles, French, German, Russian. “If your people were Russian, where would they have mined coal?” says Pinnick. He answers that on Ancestry.com by querying the US census with birthplace or nationality along with the keyword miner. He also consults Immigrants in Industry, a government series from the early 1900s (volumes 6,7 and 16 cover coal mining; find these on Google Books. (See Pinnick’s own ethnically oriented research at the African American Coal Miner Information Center.

Pinnick does check the Guide to Coal Mining Collections in the United States by George Parkinson (available at some university libraries; try interlibrary loan) and the National Union Catalog of Manuscript Collections for any existing employee records.

Historical societies, ethnic organizations, local histories and even targeted internet searches can yield fantastic images, stories, and leads, too. For example, a Google search for New River Coal Company, Fayette, WV brings up CoalCampUSA, an online encyclopedia of Appalachian coal towns. Look to pictorial histories as well, like the amazing West Virginia Panoramic Coalfield Photography, 1900-2005 by Melody Bragg (GEM Publications).

Again, look to heritage museums for the hands-on experience of coal mining. You’ll better appreciate their workday when you’ve experienced the pitch-black confines of a long shaft, or toured exhibits on the dangers they faced and life in a company-owned coal town. Find these in Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Kentucky, New Mexico, Ohio, Alabama and more. You can even tour a Virtual Museum of Coal Mining in Western Pennsylvania.

Automotive

The automotive industry revved up in the early 1900s with the birth of the “Big Three” automakers in Detroit (Ford, General Motors and Chrysler). Ford’s Model T, engineered for mass production in 1913, drove the company to fame. Competitors caught up quickly, though. By the 1930s, General Motors led the industry, followed by Chrysler.

Automobile manufacturing required a huge labor force. In 1914, Henry Ford advertised high wages to attract quality workers and reduce expensive turnover. “Ford offered $5 a day,” says certified genealogist Ceil Wendt Jensen, author of three books on Detroit history. “That was a big wage. It attracted African-Americans from other states, Italians, a lot of Eastern Europeans, Belgians, Germans, Irish—a melting pot. I have a great sign that was prominently displayed in the factory that lists one of Henry Ford’s mottos in about six languages.”

Other automakers raised wages, too. Soon workers could make a decent living without having a lot of education, explains Jensen. “That gave these families enough wealth to provide better education for the next generation.” Automakers expanded to plants in other states and around the world. Unionization in the 1930s and ’40s led to improved working conditions and guaranteed pension and health care benefits.

When it comes to researching automotive careers, “it’s not as easy as putting $25 in an envelope and sending it to metro Detroit,” says Jensen. “But the effort will be worth it. You may not find a picture of Grandma or Grandpa, but you’ll [come away with] a pretty good idea of what life was like for your family.”

Home sources

Start with home sources. “Look for union cards, employee badges, pictures from union picnics and Christmas parties, and news clippings (the auto companies were good about giving citations to workers),” says Jensen.

Next, “see what the community has in its local history room. Check local newspapers for everyday stories, ads and photos.” (She recommends using UAW, auto worker and labor as search terms in historical newspaper databases.) “Then ratchet it up a little bit with commemorative books by the auto companies that highlight the careers of leaders and workers. Use vintage maps (such as Sanborn maps) to see how your relative got to work. Did he take a streetcar or walk?”

If your relatives are still living, Jensen strongly recommends having them request their own employee records from corporate headquarters or regional plants. Your relatives are the only ones who can request these: Companies won’t release contemporary records to anyone else.

Ford

Ford is best for genealogical research, says Jensen, but its records are “hit or miss, especially with the older records.” Ford didn’t have a record on her grandfather, but it did for her father, whose employment ended in 1940. Ford sent a typed abstract of the record, not a copy of the original. Still, she was able to learn his job titles, pay rates and raises, and termination date. (Request employee records directly from the Ford corporate archives by emailing archives@ford.com.) The main Ford Historical Archive (1903 to 1955, not including employee records), is at the Benson Ford Research Center. A database of Ford employees (1918 to 1947) can be searched on campus at the University of Michigan.

Chrysler and General Motors

Chrysler and General Motors do have photograph collections in their archives, but charge fees for research and use of images. Their archives and heritage museums focus on the cars, not the workers who built them, so they have little information on rank-and-file employees. If a relative may have attended the GM Institute (now Kettering University), you can contact Alumni Affairs to confirm attendance, and Archives for yearbooks or school newspapers (grades not available except to students).

As with other industries, you’ll likely find more on your relatives (and their communities) through union histories and newsletters. “The union was a community in itself,” says Jensen, whose own family has plenty of stories about unionization. The Walter P. Reuther Library in Detroit has excellent union collections, including newspapers for many (but not all) of the UAW Locals.

“Many of the auto plants had in-house publications, too,” says Jensen. “This is where I found a story of my uncle Albert DiNatale and brothers’ employment equaling 100 years of service. Look at the Benson Ford in Dearborn for these.”

“Illustrations from these newsletters are fun,” says Jensen. “My friend Roger has a picture of his grandfather Stanley Musialowski’s retirement. He’s in a white shirt and tie, and everyone around him is in coveralls and grease.”

As director of a funded project to interview Detroit Polish-American autoworkers, Jensen also sees tremendous research value in oral histories. “We’re finding multigenerational applicants: Grandpa started on the line at Ford, the son got a little more education and was a tool-and-die guy, and the grandson was an executive. One woman we interviewed was the first female engineer at Ford, another had three generations at GM.”

Finally, if you’re considering a research trip to Detroit, leave time to enjoy the Henry Ford Museum with its historic village, antique car rides, and other hands-on reminders of your relatives’ lives. Explore heritage destinations in the MotorCities National Heritage Area.

Other Industries

Plenty more industries have boomed (and some busted) in the United States in the last 100 to 150 years, not just the ones described above. In many cases, the types of records available and places to find them are similar. Here’s a sampling of more places you can look for documents and exhibits on historical industries.

- The Archives of Industrial Society at the University of Pittsburgh holds business records of many regional companies, national union records and other labor-related materials, and a collection on African-Americans in the steel and other industries.

- The Steelworks Museum in Pueblo, Colo. documents the legacy of Colorado Fuel & Iron, reputed to have been the largest steel provider west of the Mississippi. A vast archive is attached, with original company records (such as employee applications and personnel files) and plenty of community documents (including indexed company publications).

- The American Textile History Museum covers the historical New England industry centered in Lowell, Mass. The museum’s Osborne Library has some business records, including personnel records and employee payment lists. The museum also recommends looking for mill records at Harvard University’s Business School Archives and the Center for Lowell History.

- Online directories of miscellaneous employment records are available for you to peruse at Family Tree Connection and the Corporate Archives Index.

- The Sierra Nevada Logging Museum in Arnold, Calif. honors the history of the logging industry through historical exhibits, a research resource center and a website with plenty of local history, an active blog and lots of researchers trading questions.

As you can see, most industries have a legacy you can mine. It might require some heavy-duty labor, but with perseverance and a little genealogical luck, you’ll forge a solid story of your relatives’ working lives.

Tips:

- Union or trade publications can be secondary sources for birth, wedding and death announcements and other personal information.

- Visit heritage museums for a hands-on experience of your ancestor’s everyday work life.

- Personnel files, union rosters and employee-oriented publications are difficult to find. But trade history lives on in gritty detail in photographs, oral interviews, documentaries, museums and archives.

Researching Blue-Collar Ancestors Resources

Websites

The African American Coal Miner Information Center

Glossary of Old Occupations and Trades

W&H Main Yard: Railroad Document Archives

Locations of Railroad Genealogical Materials

Books

The American Auto Factory by Barney Olsen and Joseph Cabadas (Motorbooks)

Coal: A Human History by Barbara Freese (Penguin)

American Vanguard: The United Auto Workers During the Reuther Years, 1935-1970 by John Barnard (Wayne State University Press)

Growing Up in Coal Country by Susan Campbell Bartoletti (Sandpiper)

Historical Atlas of the North American Railroad by Derek Hayes (University of California)

Railroads Across America: An Illustrated History by Claude Wiatrowski (Voyageur Press)

Organizations and Archives

Chrysler Historical Collection/Archives

Walter P. Reuther Library of Labor and Urban Affairs

A version of this article appeared in the December 2011 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

FamilyTreeMagazine.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program. It provides a means for this site to earn advertising fees, by advertising and linking to Amazon and affiliated websites.