Ancestors’ jobs can reveal so much about their lives. Occupations help you guess at a person’s income, daily life and social status. Work can explain migrations, and it places people in communities of coworkers.

As such, work records can contain a wealth of genealogical clues. Whether you’re looking for your relatives’ stories or family tree details, it’s worth the work (on your part) to look for records about theirs.

Jump to:

Determining Your Ancestor’s Occupation

What are Occupational Records?

How to Find Occupational Records

What Can You Find in an Employment Record? A Sample Record

Determining Your Ancestor’s Occupation

Before finding occupational records, you need to know what your ancestors did for a living. You may already have this piece of information in various records, including:

Censuses

Beginning in 1850, the US census population schedule includes details about the respondent’s occupation. (The earlier 1820 and 1840 censuses asked only about what category of industry the respondent worked in.) The 1880 census also asked how many months the person was unemployed. Starting in 1910, two columns described employment and three columns assessed whether the person was an employer, employee, self-employed. The 1940 census also inquired about participation in emergency work projects and total income in 1939.

City Directories

Ancestors’ year-to-year employment details often appear in city directories. These may list the type of work (“telegraph operator”) or the name of the employer (“New England Telegraph Company”) or both. Many major US cities had directories beginning in the 1800s; rural areas may not have had them until the early 1900s. Look for city directories at subscription genealogy websites Ancestry.com and MyHeritage, and a smaller but growing collection at the free website FamilySearch. Local libraries often have print collections of their old directories.

Draft Registrations

Men who registered for the WWI draft were asked for their trade and employer. WWII draft registration cards requested the name and place of an employer. Look for WWI registrations on FamilySearch and Ancestry.com. All surviving WWII draft registrations are available on Ancestry.com and Fold3, with a growing collection on FamilySearch.

Obituaries

Newspaper death notices and accompanying biographical summaries often include work history. It’s most common to find obituaries for deaths since the later 1800s. Find millions of indexed obituaries at FamilySearch or MyHeritage, or search your favorite digitized newspaper collections. Local libraries often maintain obituary clipping files or indexes for residents. Relatives who passed away within the past couple of decades may have been memorialized online; search for their names and the word obituary.

Collect all the occupation clues you can from across a person’s lifespan. Jobs and employers (and therefore the records) may have changed over time. Pay close attention to wherever a person may have worked most recently or longest, as documentation may be stronger or more meaningful.

What are Occupational Records?

Throughout US history, industries have risen and fallen in prominence, but many left behind records of their workers if you know what to look for.

Farming dominated early US jobs. The daily work varied by time period, crop, size of farm and the farmer’s status (owner, tenant, sharecropper, paid laborer or enslaved worker). Special agricultural schedules alongside the 1850–1880 federal censuses documented farmers’ improved and unimproved acreage; value of property and equipment; and the amount, value and description of livestock and produce. The 1880 agricultural census added the amount of acreage used for each crop, plus a distinction between landowners, tenants and sharecroppers.

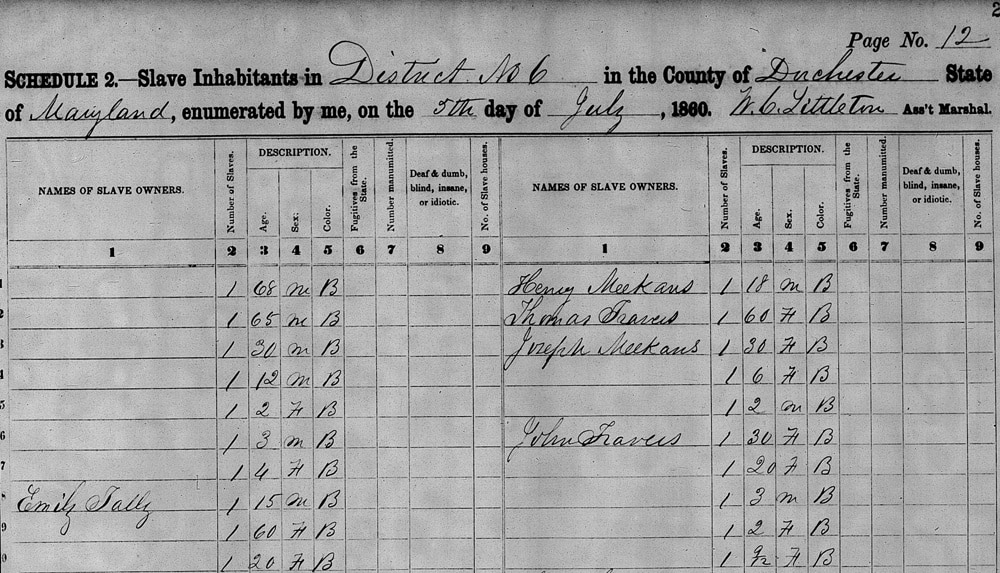

Until slavery ended, millions of African Americans performed forced labor, but it is often difficult to determine exactly what work individuals did. For the South, the 1850 and 1860 slave schedules tally (unnamed) enslaved workers by age, sex, color and enslaver name. These clues, along with additional research, may lead to informed guesses about daily work. Surviving farm or business records may be able to shed additional light.

If your ancestor enslaved people, use the slave schedules to get a better picture of the laborers who supported that ancestor’s occupation and lifestyle.

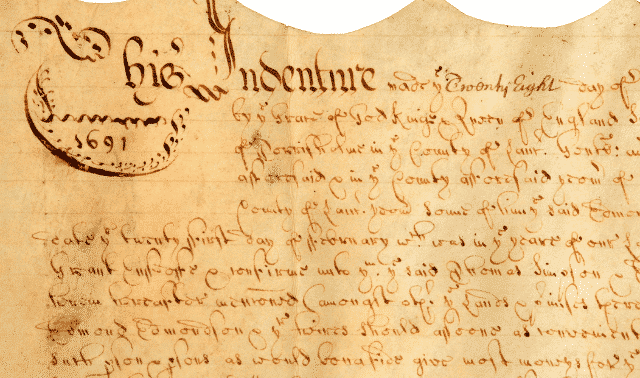

After the Civil War, the Freedmen’s Bureau documented labor, apprenticeship and indenture contracts in the South. These may reveal ancestors’ locations, type of work, payments, and any subsequent issues reported about the arrangements. The Freedmen’s Bureau oversaw all kinds of Southern aid and Reconstruction efforts; if your relatives were working in any related capacity (health care, ministry, education, supply chain, etc.), they may be mentioned.

By 1880, less than half of US workers were farmers. Various industries grew and then shrank: textile mills, mining, railroads, lumbering, steel working, newspapers. Your ancestors’ manufacturing businesses may be described—with details about products, raw materials, assets, capital invested, and numbers of employees—in the industrial or manufacturing schedules of US censuses (taken 1810–1820 and 1850–1880).

Businesses themselves generated records that vary by time period, industry and the size of an enterprise. Large companies may have kept group payroll lists or—better yet—individual employee records with personal identifying information; previous employment; wage and position history; and comments on performance and retirement. Records may indicate reasons for changes in employment, such as moving, injury, strike, layoff or a woman’s marriage or pregnancy. Group payroll lists may capture some of this information, too.

Some companies also published newsletters, histories, employee manuals or promotional brochures. These may mention your relatives or show them in individual or group photos. The stories and pictures can help you understand their employees’ work environment, machinery, processes and work culture. You might see how production of goods or services changed during the time your relative worked there.

What about people who didn’t work at big companies? Farmers, midwives, clergy, millers, storekeepers, doctors and others sometimes kept ledgers or books detailing their professional activities, clients or patients, inventory and financial records. Because paper was precious, you might find personal and family details in these ledgers, too. Someone else’s business records may list your ancestor as a customer or client.

Various government offices created records about businesses, too. Local or state licenses may have been required for tavern owners, pharmacists, nurses, doctors, teachers, attorneys, funeral directors and others. Licenses may document an applicant’s address, profession, licensing history and job history. Tax records might document ancestral residences year by year, along with fees paid and what property or income was being taxed. Litigation or bankruptcy proceedings in court records may reveal stories and challenges about your relatives’ business dealings.

Government agencies themselves also employed people. Military service probably generated the most detailed, genealogically-rich paperwork. Documents range from draft registrations to service records to pension files.

Federal civilian employees, including those who worked for the Depression-era Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) or Works Projects Administration (WPA) programs, also generated files with personal identifying and employment details. Postmasters and postmistresses generated records of appointment, which document the place, time and length of a relative’s service.

Professional, trade, labor and sporting organizations created their own records, too. Basic membership lists may only mention members and perhaps their addresses. But sometimes these records have more details, such as dues payments, organizational involvement, and professional activities or performance. Benefits organizations (such as for deaths or burials) would have created the most extensive documentation, with birth and death, next-of-kin, work and health history information.

How to Find Occupational Records

Your success in finding ancestors’ job records depends on what was created, what has survived and how accessible they are today. Each of those factors, in turn, were affected by other particulars of records creation and storage: the time, place, industry, diligence of records custodians, privacy regulations, and index or digitization status.

Many special census schedules, including surviving slave, agricultural and industrial schedules, are online. Explore the 1850 and 1860 slave schedules at FamilySearch and Ancestry.com. Agricultural and industrial schedules have been compiled by Ancestry.com.

Business records, especially those that remain in corporate archives, may be open to research inquiries. If a company is still in business, search its website for a corporate archive. (If companies have merged, reorganized or been sold, you may need to research the current company’s name.) Ask whether individual employee records survive for the time period, whether copies are available, and what additional resources can help you understand that person’s work experience there.

Many old business records are now in public, university, regional or private repositories. Search your web browser with keywords such as the name and location of the company and the type of work. Watch the search results for descriptions of that company’s records at an archive. For example, a search of Pullman Company Employee Records brings up the collection at Chicago’s Newberry Library.

ArchiveGrid is a free online catalog with more than 7 million archival holdings in over 1,400 libraries, archives and museums. Search it using occupations, employers and places as keywords. If you enter Dallas Texas textile mill, you’ll find an entry for a mill’s employee timekeeping lists and wages for 1937 and 1938. Not all archival collections have been cataloged there, so ask historical societies and regional archives about original records for local businesses.

Some kinds of records, such as manuscript collections, haven’t been digitized, so you’ll have to visit archives in person or hire the staff or a local researcher. Furthermore, business record collections aren’t usually indexed, unless employee records happened to be kept alphabetically. The downside is that you’ll have to spend time searching for mentions of ancestors. The upside can be that you’ll get a fascinating new perspective on what it was like to work there.

What about civilians employed by the federal government? Request copies of Official Personnel Folders for civilian employees (1850–1951), including workers for WPA projects and the CCC, from the National Archives. Researching a postmaster or -mistress? You can learn about appointment records at the National Archives as well.

Occupational Record Substitutes

Plenty of other records may provide context and clues about your ancestors’ working lives. Search local newspaper advertisements for stores, professional services, and cottage industries like boarding houses or laundries. Businesses and workers—from professional boxers to prostitutes—appeared in news stories, too. (If you find criminal activities, don’t forget to follow up in court records.)

How-to books for homemakers and a wide variety of occupations appeared in print over the decades. A guide to carpentry or home-preservation methods for your ancestor’s time period can provide insight into daily tasks and methods.

Those who built, invented, created or repaired things may have left behind material evidence. Artists, architects, musicians, writers, mapmakers and artisans may have signed their work. Engineers, tinkerers or inventors could have filed for patents. For those whose work went unsigned—think dressmakers, jewelers, milliners or blacksmiths—look instead for any surviving items that hint at the kinds of things they would have made.

Finally, seek out published articles or books about specific trades or industries, such as migrant agricultural workers or coal mining. Some histories even focus on regional industries (Chicago meatpacking) or those associated with specific ethnicities (Chinese railway workers). Search for documentary films on YouTube or at your local library. These will give you insight to your ancestor’s daily routine, working conditions, and quality of life.

What Can You Find in an Employment Record? A Sample Record

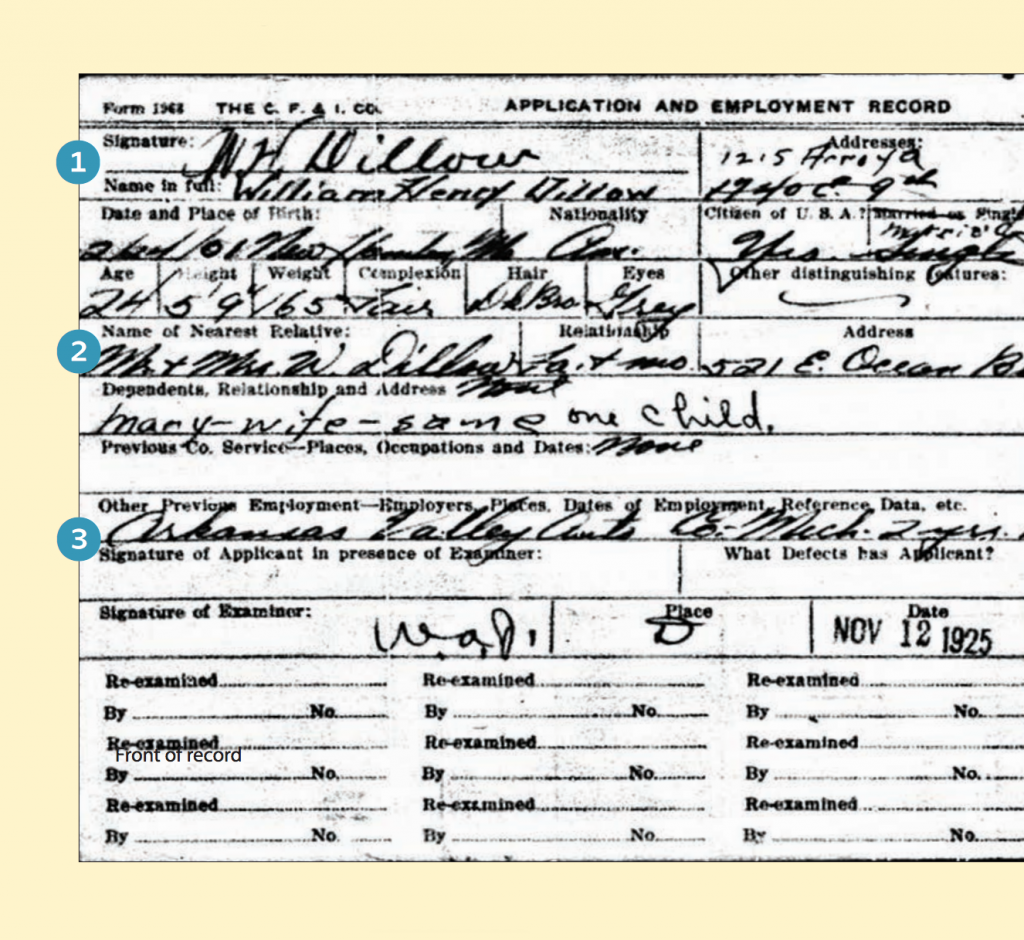

Let’s take a look at an example employment record to see what information we can find. To see the whole record front and back, click here.

1. Identifying information in employment records may vary. This one includes name, signature, address, date and place of birth, citizenship, marital status, age and physical description.

2. Watch for notes about next of kin, like this request for the name, relationship and address of the applicant’s nearest relative, as well as dependent details.

3. Previous employment can tell you where a relative lived, what kind of work they did, and what additional companies might have kept records.

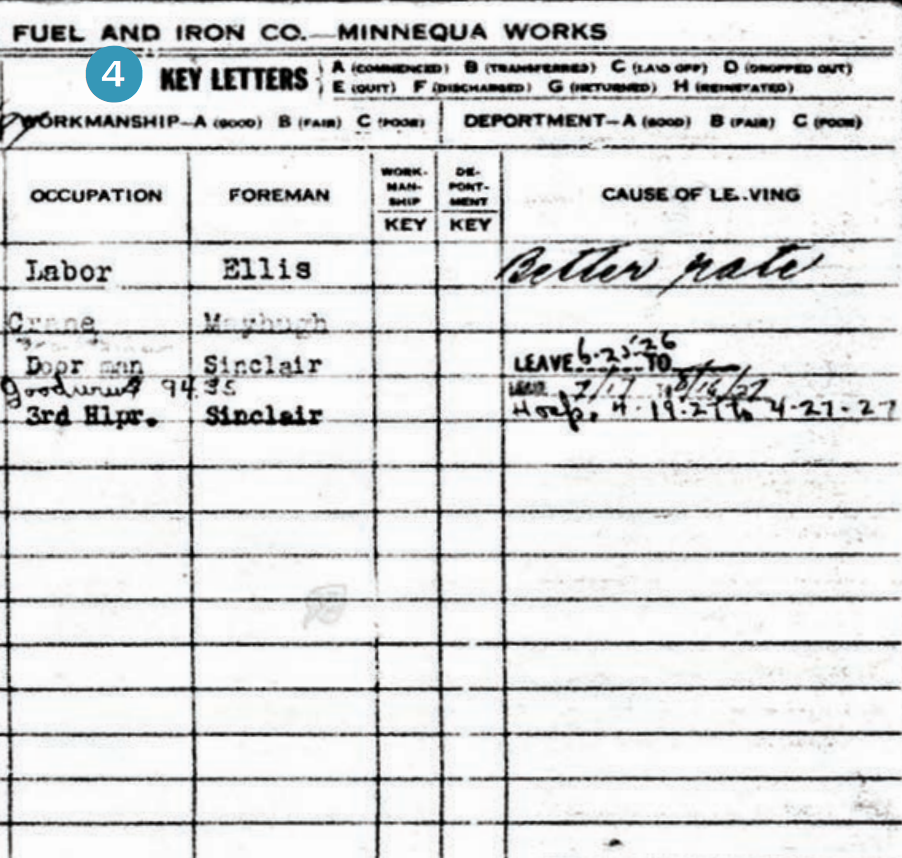

4. Watch for codes and instructions that will help you understand what you see. Here, letters correspond to HR-related events such as employment beginning and the employee being transferred or laid off.

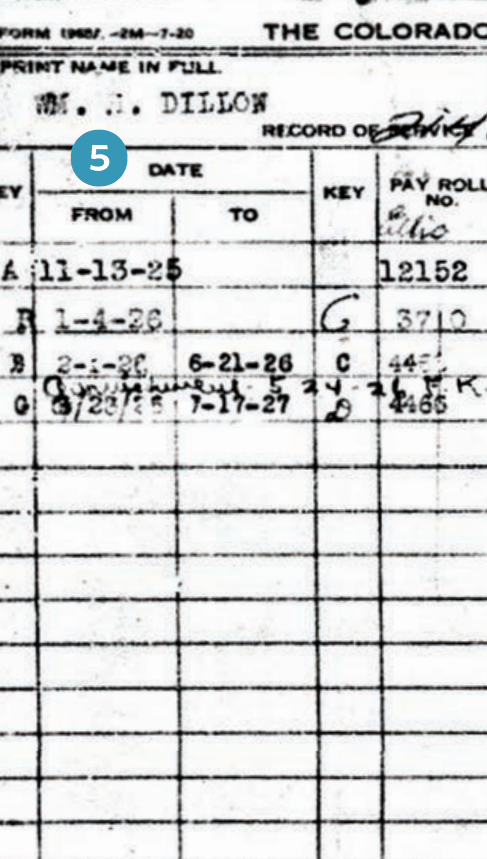

5. Work history notes can reveal the employee’s changing positions and pay rate; injuries; and employment disruptions and reasons for status change.

A version of this article appeared in the January/February 2022 issue of Family Tree Magazine.