So you’re hunting for your great-grandpa Norwood Adams, born about 1883 in North Carolina, and you’re thrilled to finally find him in the 1910 census. But what’s he doing in Fulton County, Ga.? And why does his “family” seem to consist entirely of men—Will C. Williams, age 29; Thomas Warden, 39; Jacob Williams, 28; William Lewis, 28; and so on? A little squinting at the fine print reveals Great-grandpa’s “relationship” to these fellas: They’re all inmates at the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary.

At first, finding a felon or other ancestor with a criminal past in your family tree may be a bit disconcerting. After all, genealogists love to brag that their ancestors came over on the Mayflower, not on a prisoner-transport ship. And we’re always looking for familial links to royalty or Colonial governors, not for ancestors those esteemed officials sentenced to hanging.

But look on the bright side: An ancestor with a criminal past adds a colorful character to your family history. Not to mention the potential to unlock a wealth of genealogical data denied to those whose ancestors stayed on the straight and narrow. Great-grandpa Norwood Adams, for example, turns out to have been a counterfeiter. At the National Archives’ and Records Administration’s (NARA) online index to Atlanta Federal Penitentiary inmate case files, you’ll discover he was 27 years old at his sentencing in New Bern, NC. By writing NARA’s Southeast Regional office for the file or hunting down trial records, you could learn Adams’ details about genealogy and penchant for “passing paper.”

So you see, the only shame in having an ancestor on the left side of the law would be ignoring the windfall of family history resources we’re about to describe.

“Black Sheep” Ancestors

Keep in mind that way back when, folks went to jail—or were transported halfway around the world to prison colonies—for offenses that today would barely warrant a slap on the wrist. Vagrancy was a common charge, and being unable to pay your debts could get you locked up. “Crimes” including sacrilege, fishing in somebody else’s pond and a “secret marriage” could get Britons shipped to the Colonies or Australia (see box, below), as could thefts of as little as a shilling. So there’s not necessarily a lot of shame associated with having a “criminal” in your pedigree.

Heck, entire organizations are devoted to those with “black sheep” kin—the International Black Sheep Society of Genealogists, for one. In addition, there’s a Blacksheep Ancestors blog and BlacksheepAncestors.com to help you research forebears the rest of the family would rather not discuss.

Depending on the nature of your ancestor’s wrongdoing, you can commingle with fellow descendants of Wild West outlawsor fly a skull-and-crossbones pennant from your family tree. Related to an infamous outlaw? Other genealogists may have done genealogical research on him, as they have for the members of the Dalton Gang.

Because non-genealogists in families tend not to talk about “black sheep,” you may have to do some digging to uncover an ancestor’s criminal past. Indeed, the very reason you keep running into a “brick wall” in your hunt for a particular ancestor could be his time spent behind the well-guarded walls of a jail or prison. Family rumors; old letters (an “Alcatraz” postmark is a dead giveaway); newspaper clippings; and documents such as old legal bills, release papers and pardon certificates can offer clues, as can old newspapers.

Surprisingly, perhaps, so can the federal census. Yes, inmates were enumerated even if they happened to be behind bars in a census year. When you can’t locate an ancestor in his home state or town, try widening your search. Online census databases can ferret out people—like Norwood Adams—residing in unexpected locales, such as a prison. You can search and view all available US census records on Ancestry.com and its sister service Ancestry Library Edition (free at many libraries). HeritageQuestOnline.com, also free through many libraries, indexes most censuses (you can browse the unindexed records). Fold3 offers the 1860 and 1930 censuses; FamilySearch has several censuses you can access for free.

Criminal Court Records

Once you’ve identified a suspect, so to speak, you can start researching where your crooked kin’s rap sheet began—in court files. The trick here is to figure out which court had jurisdiction over the crime in question, and what’s become of those old records. In the United States, minor offenses such as shoplifting or public drunkenness typically fall under the purview of a municipal or a county court. More serious crimes would probably land the perpetrator in state court. Crimes that cross state lines, such as counterfeiting, as well as those committed on federally owned land, wind up in federal court.

With the exception of cases involving juvenile defendants, most criminal court records on any level are open to the public. The challenge is locating where they’ve been stored. Like other local records, old municipal and county court records might’ve been sent to another repository or relocated with changing county lines. The pages for each state at the volunteer site USGenWeb are a good place to start. The Sourcebook of County Court Records, 4th edition, edited by Michael L. Sankey, Carl R. Ernst and Jimmy Flowers, can guide you to the right repository (BRB Publications, out of print). You can also try a simple Web search for county court records and the name of the county.

Often, older municipal and county court records have been transferred to the state archives or historical society, which is probably where you’d also find state court records. A smattering of these are online: Members of the New England Historic Genealogical Society, for example, can search databases of early Connecticut court records, an index to Maine court records (1696 to 1854), Plymouth, Mass., court records (1686 to 1859) and abstracts of early Middlesex County, Mass., court files.

Most federal court records are at the NARA branch nearest the court. For a guide to NARA’s holdings of federal district court records, including criminal courts, see the archives’ website. Some of these records also are on FHL microfilm.

When you find an ancestor’s court records, make note of the docket number. Most courts use this number to track a case as it winds through the system. You’ll want to follow your ancestor’s case all the way through any appeals to final sentencing. If he was found guilty, go directly to jail or prison records.

Incarceration Records

Happily for you, if not for your scofflaw ancestor, being put behind bars generates a raft of paperwork. Facts found in prison records vary, but often include parents’ names and places of birth, plus information about the inmate’s spouse and children, religion, health, education and non-criminal occupation (if any).

As with court records, finding incarceration records is mostly a matter of first identifying the jurisdiction or institution, then tracking down where those records are now kept.

Generally, criminals convicted in one level of court are assigned to a corresponding lockup. Local and county courts typically sentence criminals to a municipal or county jail. You can start with the county clerk’s or sheriff’s office to inquire as to the whereabouts of historical prison records—as with court records, these may have been transferred to a state archive or historical society. The Pennsylvania State Archives, for instance, now houses the files of the Allegheny County Work House. You also can find microfilmed jail records in the FHL catalog by searching for a place, then looking for a correctional institutions heading.

Records for state prisons are more readily available than local ones, and again, the state archives is the place to start. For instance, the aforementioned Pennsylvania archives holds records from the Eastern State Penitentiary (prisoners from eastern counties, 1829 to 1934), the Western State Penitentiary (1826 to 1960), and the Industrial Reformatory at Huntingdon (for first-time-offender males ages 15 to 25, 1889 to 1932). The Minnesota Historical Society has a broad range of criminal records, from patient registers at the Minnesota Security Hospital (1864 to 1924) to inmate case files at the State Reformatory for Women (1919 to 1977). See a guide on the archives’ website.

The Texas State Library and Archives Commission holds 29 ledgers covering Lone Star inmates from 1849 to 1954, plus 10 indexes for 1849 to 1970. Information on inmates can include a physical description, tobacco use, education, occupation, birthplace and residence. In late 1891, such genealogical goodies as date of birth and parents’ birthplaces were added. Kinda makes you wish your Texas kin had gone astray, huh?

In some states, the department of corrections holds onto historical records. The Illinois Department of Corrections will research convict kin for no charge: Go to the department’s website and click on IDOC Webmaster to bring up an e-mail form where you can fill in as much as you know about your ancestor.

Other states have put some prison records online—chiefly indexes, which can at least confirm where an ancestor was incarcerated. Inmates of the Tennessee State Penitentiary from 1831 to 1850 are indexed online; archives staff also will search a collection of prison records covering 1831 to 1870 at no cost. You’ll find an index to Arizona inmates from 1872 to 1972 here. The Connecticut State Library has a searchable database of inmates at the Wethersfield Prison, 1800 to 1903.

You can find a collection of state prison records from Alabama, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Maine, New Hampshire, New York and Vermont, mostly for single years between 1869 and 1910, at Genealogy Today.

Federal prison records, like federal court files, reside at NARA’s regional offices. You can find indexes to inmates at Alcatraz, Leavenworth and the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary, plus photos from the McNeil Island Penitentiary. There’s also an Alcatraz roster covering 1934 to 1963.

The Federal Bureau of Prisons can help, too. See page 55 for guidelines on requesting information about inmates released prior to 1982. You must provide the inmate’s name (including the middle name or initial), date of birth or approximate age at the time of incarceration, race, and approximate dates he or she was in prison.

Don’t overlook the possibility your ancestor died while incarcerated. If no one claimed the body, he may have been buried at the prison. Interment.net features a transcription of tombstones from Fort Leavenworth Military Prison Cemetery and listings from a few other jail graveyards. Find A Grave has cemetery transcriptions from institutions such as Stateville Prison in Joliet, Ill.

Newspaper Articles

Old newspapers are invaluable for tracking down criminals in your clan, potentially letting you read about your ancestor’s arrest, trial and conviction. Search the Chronicling America newspaper directory to find titles covering the date and place of your ancestor’s crime; if you’re lucky, that newspaper might be among the searchable collections on GenealogyBank or another subscription site. Public libraries and law libraries may hold accounts of criminal cases involving a notable felon, so check county and legal history books.

Other genealogists might’ve transcribed the court or prison records you’re after. Check the Periodical Source Index (PERSI) at HeritageQuest Online, which catalogs historical and genealogical journals. You could find, for example, an article on “Baltimore City Police criminal dockets, an underused resource” or “Criminal executions, guide to online records, 1726-1961.”

Ah, yes, about that last example. If your criminal ancestor was not only imprisoned but also executed, you’re certain to find no shortage of court records and newspaper accounts. Tough luck for your ancestor, yes, but a truly colorful tale for your family history and an unusual annotation to the “death” citation in your pedigree file. Just let the Mayflower crowd try to top that.

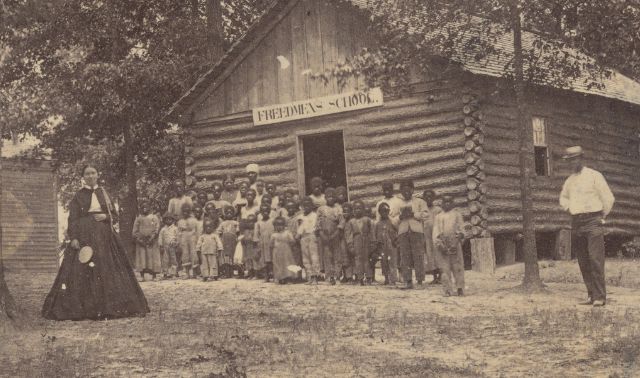

Finding UK Criminal Ancestors

Sometimes criminals and debtors weren’t simply sent to prison—they were shipped to another continent. Britain began exiling convicts to the Americas, including Virginia and Maryland, in the 1700s. James Oglethorpe advocated the establishment of a colony, which in 1732 became Georgia, as an alternative to the teeming debtors’ prisons of England. Though promoted as a destination for the “worthy poor,” Georgia was never exclusively a penal colony.

Historian Peter Wilson Coldham puts the total number of convicts conveyed from the British Isles to America at almost 50,000, which would represent as much as one-quarter of all 18th-century British emigration. France also shipped some of its convicts abroad to its territory in Louisiana.

Coldham’s listing of convicts sent to the Colonies, collected as British Emigrants in Bondage, 1614 to 1788, has been reproduced on a CD (Genealogical Publishing). For background, you can also consult Bound for America: The Transportation of British Convicts to the Colonies, 1718 to 1775 by A. Roger Ekirch (Clarendon).

“Transported” convicts in the Colonies were little different from slaves, assigned to work without wages for a master for a term of seven or 14 years. During that time, they couldn’t marry or own land. They often ran away, so you might find a convict ancestor in newspaper runaway advertisements of the period. When their bondage term was done, the convicts were simply released to make their own way, without receiving the “freedom dues” paid to indentured servants.

Britain’s prisons grew ever more crowded after American independence shut off its prisoner dumping ground. Old ships—called “the hulks”—were converted into floating prisons, moored along the coast. But Capt. James Cook, in 1770, had already discovered a possible solution when he mapped New South Wales and claimed Australia for Great Britain. In 1787, the First Fleet set sail from England for the new penal colony. By the end of “transportation” in 1857, roughly 40 percent of the English-speaking population of Australia consisted of transported convicts.

Ancestry.com has four online collections of Australian convict registers, divided by time period. You also can consult an 1828 census of New South Wales and three convict lists/musters, which include Tasmania, all searchable on Ancestry.com. The UK national archives has an online database of Irish convicts transported to Australia. See Convict Central for more resources

There are also the proceedings of the Old Bailey, 1674 to 1913, covering nearly 200,000 trials in London’s central criminal court.

The UK National Archives catalog lists a collection of petitions for clemency, wherein might be a letter your ancestor wrote to the judge; its online collection includes Victorian prisoners photos.

For a quick way to identify criminal ancestors in the UK, go to the archives’ catalog search. Enter a name (or just a surname) in the Word or Phrase box and type HO 47 in the Department or Series Code field. That restricts your search to a series of judges’ reports on criminals, spanning 1783 to 1830. Hits will give you a quick summary of why your ancestor was in hot water (“Report of Francis Buller on John Waltho, farmer, convicted at the last Staffordshire Assizes, for stealing 3 sheep, property of William Hanson, from Kings Bromley Common during the first week in October 1785 … ”); the original documents are in the archives in Kew.

For more on catching criminals in the UK’s archives, see Looking for Records of Crime and Punishment.

Descendants of Scottish scofflaws needn’t feel left out. Check the lively (yes, really) site for Inverary Jail, where you can search records of more than 4,300 prisoners—including those who were ultimately transported.

A version of this article appeared in the November 2009 issue of Family Tree Magazine.