Notice how my grammar improved?

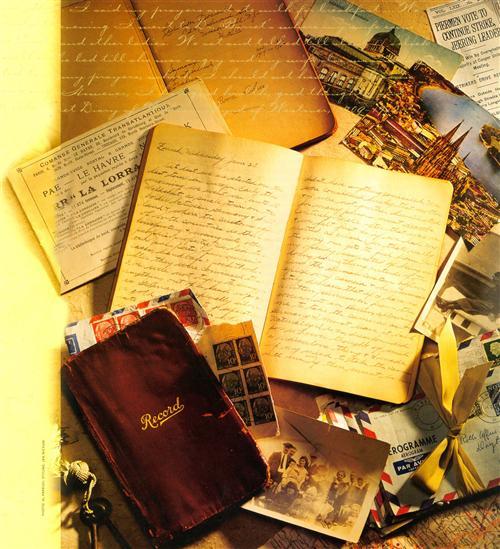

Diaries recount for us firsthand what it was like to live during a given time period and at a particular place. These accounts are the autobiographies of ordinary people, and may be the only exiting records of there personal lives. If your ancestor kept a diary or journal and it survived the years, reading I can bring alive your family’s past more powerfully than almost anything else short of time travel.

Although the terms diary and journal have been used interchange-ably, diaries tend to record people’s feelings, while journals focus on activities and events. Either can give you genealogical data, as well as some glimpse into the writer’s daily life thoughts and attitudes. A diarist may also record his or her felling on national events, such as a war or its impact on that person, the family and the community.

It was more common for women to keep diaries then men, but women tended to do so only during periods of emotional stress such as time of war, moving away from family and friends of separation from their spouse (if the husband was out West in search of gold, for instance). Diaries may have been written with the knowledge that one day they would be shared, such as travel diaries meant to be read by those left at home. Marie Bashkirtseff, who died at age 24 from tuberculosis, kept a journal (excerpted in Revelations: Diaries of Women by Mary Jane Moffat and Charlotte Painter, Vintage Books) she intended for someone to read after her death:

July 23, 1965

I played school with fat Jane. Me and Jane had a fight.

July 24, 1965

I was nine when I wrote those entries in my first diary. I’m so glad my notation have matured over the past 35 years:

February 16, 2000

Beth and I had an argument today. We went shopping for new dresses, and when I told her that the one she like best made her look fat, she got upset.

What if, seized without warning by a fatal illness, I should happen to die suddenly! I should not know, perhaps, of my danger; my family would hide it from me; and after my death they would rummage among my papers; they would find my journal, and destroy it after having read it, and soon nothing would be left of me — nothing — nothing — nothing! This is the thought that has always terrified me.

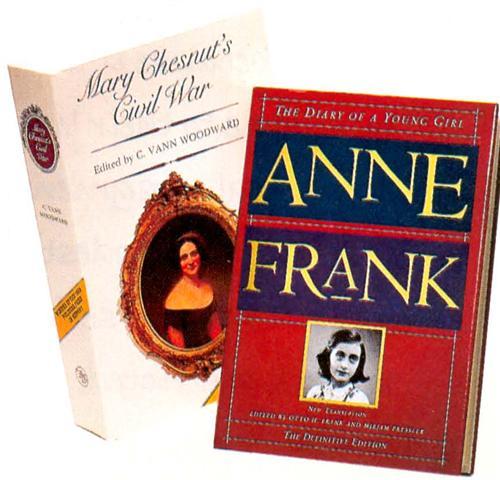

And where would literature and history be without the publication of Anne Frank’s The Diary of a Young Girl?

Diaries don’t have to be written by famous people or tell about historic events to be valuable. In fact, the diary your ancestor may have written will likely contain the routine, the boring and the mundane. But that’s what makes them so valuable to us and to social historians. We can read about famous events and people in the newspapers — but we can only learn about ordinary people’s daily lives from their written accounts.

For example, women of the Quaker religion were encouraged to keep spiritual journals to be published and shared with other women. About 3,000 had been printed by 1725. Howard Brinton’s Quaker Journals: Varieties of Religious Experience Among Friends (Pendle Hill Publications) and Luella Wright’s Literary Life of the Early Friends, 1650-1725 (AMS Press) are two invaluable sources if you have Quaker ancestry; these books also list the whereabouts of surviving originals. Be aware, however, that these diaries were edited before they were published; any passages that were contrary to Quaker beliefs were eliminated. Many women who moved to the frontier kept travel diaries. Along with documenting births and deaths, they also recorded the daily tedious activities of washing, baking, unpacking and packing, the number of miles the family traveled, the presence or absence of grass for the cattle. This diary entry (excerpted in Women’s Diaries of the Westward Journey by Lillian Schlissel, Schocken Books) was written by Catherine Haun, who journeyed across the plains in 1849:

Every heart was touched and eyes full of tears as we lowered the body, coffinless, into the grave. There was no tombstone — why should there be — the poor husband and orphans could never hope to revisit the grave and to the world it was just one of the many hundreds that marked the trail.

Reading their diaries

If you have a diary or journal by one of your ancestors, you have a special source. Read carefully the notations on the diarist’s birthday and at the beginning of the new year, since these tend to be times of reflection and self-evaluation.

In women’s diaries, look for coding: Women commonly coded their diaries with a mark to denote their menstrual cycles. In Seasons for Growing: The Diaries of Lizzie A. Dravenstatt, 1870-1928, edited and published by Patricia Sanford Brown, when Dravenstatt was between 42 and 46 years old, she marked a date almost monthly with an asterisk. As she aged, the marks were farther and more erratically spaced until the last notation in 1901, when she likely reached menopause. Though she frequently complained of illnesses and feeling bad, these asterisks were always accompanied with a remark either for that day or the following day of feeling bad.

Another common code in diaries of both women and men is the use of only initials for people the diarist wrote about. There’s nothing more frustrating than to find an entry recording a rejected marriage proposal from “K.T.,” with no other clue to identify the suitor. If your ancestor lived in a small community, however, you may be able to figure out the identity through research in other records — that is, assuming the diarist used more than one initial. Common also was “J — came to visit today.” This wasn’t necessarily an attempt to be secretive. Why should your ancestor write out the whole name? He knew who he was writing about.

Even if your ancestor’s diaries haven’t survived, perhaps diaries exist by one of your ancestor’s relatives, friends or neighbors. These may contain material about your ancestor, and they can give you a glimpse into what your ancestor’s life was like, since these diarists probably came from the same socioeconomic background.

Finding diaries, step by step

But how do you discover if your ancestor has surviving diaries, or if friends, neighbors or relatives left any? The first step is to contact all of your relatives to see if they might have a diary of one of your ancestors. Even if you’ve already bugged your relatives for family history information, it’s worth asking them specifically about diaries. This may trigger a memory that hadn’t surfaced in previous inquiries.

Next try placing a “query” or advertisement in one of the genealogical research magazines such as Evertons Genealogical Helper (Box 368, Logan, UT 84321) or Heritage Quest (Box 329, Bountiful, UT 84011) to see if some distant relative whom you haven’t discovered yet might be in possession of an ancestor’s diary. You can also post queries on Web sites and in Internet newsgroups; Cyndi’s List of genealogy sites is a good starting point to find these <www.cyndislist.com>.

Also check the area where your ancestor lived. Write or visit the state historical society, library or archive or local university and public libraries that may have area history or special collections. Ask if they have any diaries by your ancestor or relatives or neighbors. You may also want to consider placing an ad or writing a letter to the editor of the local newspaper where your ancestor lived to see if any descendants are still in the area who may have an old diary.

Keep in mind, however, that diaries can end up virtually anywhere. For example, the Tutt Library of Colorado College in Colorado Springs has the diary of Sophronia Helen Stone in its special collections. Her diary covers her overland journey from New Lebanon, Ill., to Yreka, Calif., in 1852. Although she never lived in Colorado Springs or anywhere in Colorado, her diary was donated to the college by a professor who taught part-time at the college in 1948-49. So your ancestor, who lived his entire life in Virginia, may have kept a diary that’s now in a repository in New Mexico, because the descendant who inherited it lived there and donated it.

How do you find these strays and whether or not a diary may exist in a repository? Start with the National Union Catalog of Manuscript Collections (NUCMC, affectionately referred to as “nuck-muck”). NUCMC has been published annually since 1959 by the Library of Congress, which asks repositories all over the United States to report their manuscript holdings. You can find the NUCMC in reference departments of college and university libraries and in large public libraries. The two-volume Index to Personal Names in the National Union Catalog of Manuscript Collections 1959-1984 is especially helpful.

Another reference guide for women’s diaries in particular is Andrea Hinding’s Women’s History Sources: A Guide to Archives and Manuscript Collections in the United States. Here’s a typical entry:

Goltra, Elizabeth Julia. Papers. 1853.21 pp. Univ. of Oregon library, special collections. Journal describing a journey across the plains from Mississippi to Oregon.

This guide also has a geographical index that makes it useful for checking the area your ancestor and neighbors lived. Look for it in the reference section of larger libraries.

Published, not perished

Don’t overlook the possibility that your ancestor’s diary might have been published, either in its entirety or as part of an anthology. Diaries are hot items for publishers, especially women’s diaries and diaries of people who lived during the Civil War.

As with the Quaker diaries mentioned earlier, however, be cautious of published diaries. Read the editor’s introduction to determine if the diary has been published in its entirety. For example, Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s A Midwife’s Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard, Based on Her Diary, 1785-1812, is not a full transcription of Martha Ballard’s diary, but Robert and Cynthia MacAlman McCausland’s The Diary of Martha Ballard, 1785-1812 is. Some editors may choose to emphasize certain aspects of the diary, depending on their goal or theme.

Also check the Internet for diaries. (Now there’s a comforting thought: Someday one of your descendants may scan and digitize your diary so the whole world can read it!) Repositories such as Duke University’s Special Collections Library have posted diaries on the Web <scriptorium.lib.duke.edu/collections/civil-war-women. html>. Type in “diaries” in your favorite search engine and see what happens. (You can search nine top Web search engines with one click at <www.familytreemagazine.com/search/general.asp>.) As an example, in About.com’s search <www.about.com> under “diaries,” then “historic diary,” it gave me 43,105 links!

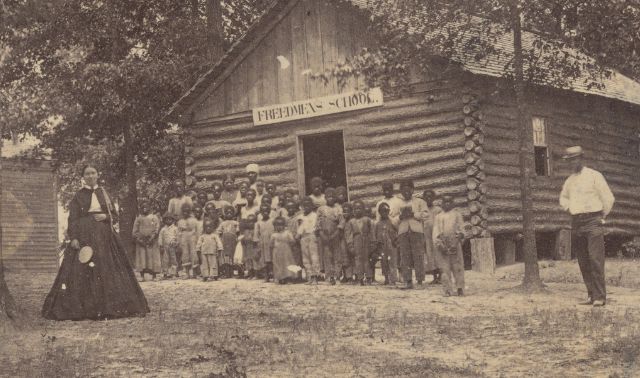

If you’re still coming up empty-handed for diaries of your ancestors and their friends, published diaries from the same geographic area, time period and socioeconomic class can at least give you a feel for what their life was like. My third-great-grandmother was a plantation mistress in Virginia. Although, to my knowledge, a diary for her doesn’t exist (if she even wrote one), I can still step back into her past by reading diaries of other plantation women in similar circumstances.

A diary of your own

So are you keeping a diary for your descendants? Shame on you if you’re not. Knowing how thrilled you’d be to find an ancestor’s diary, how can you deprive your descendants of that same joy? “But my life is so routine, so boring,” is a common response. Yes, our lives do seem routine and boring — to us. Many of my diary entries read, “Did laundry. Read a historical romance novel.” Not exciting stuff. But wouldn’t you just love to find your grandmother’s diary that recorded daily activities like these? Her life was no more exciting than yours, but at least you would know what it was like.

Make the decision to start today. Although you may find it easier to record your daily activities and thoughts on a computer-generated diary, keep in mind that your descendants will want to see your handwriting. That’s part of the ambiance of a diary. Once you discipline yourself to set aside five or ten minutes a day for this invaluable activity, you will find that it isn’t a chore after all. For help in getting started, see the Web site for Personal Journaling magazine <www. journalingmagazine.com>, also from the publishers of Family Tree Magazine.

Afraid someone might read your diary before you’re gone? Or, horrors, publish it the minute you are? Of course, you can always find a safe place to hide your diaries. Mine are stored in a locked, fire-safe file box. And you can put a stipulation in your will as to who you want to inherit your diary. You can also stipulate that your diary may not be published, or that it may only be published a certain number of years after your death. By then, anyone you might embarrass will also likely be dead.

So am I concerned about my 35 years of diaries being published one day? You bet. I’m like Marie Bashkirtseff: I’m afraid my descendants won’t publish them, but will destroy them after they’ve read them. My life may not have all the excitement of a pioneer woman’s, but it will definitely make for some interesting reading one day. Oh, and don’t worry, M -, R -, J — and you too, Fat Jane, I’ve stipulated in my will that my diaries are not to be published until 50 years after my death. Our secrets are safe — well, for the time being, anyway.

[Diaries have] been an important outlet for women partly because it is an analogue to their lives — emotional, fragmentary, interrupted, modest, not to be taken seriously, private, restricted, daily, trivial, formless, concerned with self and endless at their tasks.

– Mary Jane Moffat, Revelations: Diaries of Women

Finding a diary

Check for these books in larger public and academic library reference collections:

• American Diaries: An Annotated Bibliography of Published American Diaries and Journals by Laura Arksey, Nancy Pries and Marcia Reed

• New England Diaries, 1602-1800: A Descriptive Catalogue of Diaries, Orderly Books and Sea Journals compiled by Harriette Forbes

• The Published Diaries and Letters of American Women: An Annotated Bibliography compiled by Joyce D. Goodfriend

• American Diaries: An Annotated Bibliography of Published American Diaries Written Prior to the Year 1861 and American Diaries in Manuscript, 1580-1954: A Descriptive Bibliography both compiled by William Matthews

On the bookshelf

OTHER PEOPLE’S DIARIES

• Secret and Sacred: The Diaries of James Henry Hammond, A Southern Slaveholder edited by Carol Bleser (University of South Carolina Press)

• A Diary of the Century: Tales from America’s Greatest Diarist by Edward Robb Ellis (Kodansha International)

• The Diary of a Young Girl: The Definitive Edition by Anne Frank, edited by Otto H. Frank and Mirjam Pressler (Doubleday)

• The Diary of Martha Ballard, 1785-1812 edited by Robert McCausland and Cynthia MacAlman McCausland (Picton Press)

• Mary Chesnut’s Civil War by C. Vann Woodward (Yale University Press)

• A Midwife’s Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard, Based on Her Diary, 1785-1812 by Laurel Thatcher Ulrich (Vintage Books)

• The Secret Diary of William Byrd of Westover, 1709-1712 edited by Louis B. Wright and Marion Tinling (The Dietz Press)

DIARY ANTHOLOGIES

• A Women’s Diaries Miscellany by Jane DuPree Begos (Magic Circle Press)

• A Day at a Time: The Diary Literature of American Women from 1764 to the Present by Margo Culley (The Feminist Press)

• Private Pages: Diaries of American Women, 1830S-1970S edited by Penelope Franklin (Ballantine, out of print)

• Covered Wagon Women: Diaries and Letters from the Western Trail, 1840-1890, 11 volumes, edited by Kenneth L. Holmes (Arthur H. Clark)

• The Book of American Diaries: From Heart and Mind to Pen to Paper — Day-by-Day Personal Accounts Through the Centuries by Randall M. Miller and Linda Patterson Miller (Avon Books)

• Revelations: Diaries of Women by Mary Jane Moffat and Charlotte Painter (Vintage Books)

• A Quilt of Words: Women’s Diaries, Letters and Original Accounts of Life in the Southwest, 1860-1960 by Sharon Niederman (Johnson Books)

• Women’s Diaries of the Westward Journey by Lillian Schlissel (Schocken Books)