Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Tuberculosis sanatoriums. State hospitals. Poor farms and almshouses. “Insane” asylums. Old folks’ homes. Orphanages. Prisons. Almost everyone has a relative who—whether willingly or not—became a resident in an institution for a short period or even the better part of a lifetime. Or perhaps an ancestor or relative worked in an institution.

The sister of my relative John Norris committed him to the Connecticut Hospital for the Insane at Middletown, Conn. My mother’s cousin Ralph McCue spent time in a tuberculosis sanatorium in Lake Placid, NY, then was transferred to Saranac Lake’s Trudeau Sanatorium. While relatives like my uncle John and cousin Ralph might be only whispered about among the family, ancestors’ institutionalizations created records that genealogists shouldn’t be shy about seeking. These records can provide a unique insight into our ancestors’ health, social and financial status, and misfortunes and misdeeds—and sometimes genealogical details not documented anywhere else.

Searching for clues

When families are secretive about institutionalized ancestors, it can be difficult to know where to look for records. When a family rumor or mysterious disappearance arouses your suspicion that a person was incarcerated or committed, start with these sources to try to figure out whether he was, and if so, when and where:

Family sources: An institutionalized relative or ancestor is sometimes a skeleton in the family closet, and relatives may be the first place you learn about a commitment. While family members might not immediately volunteer the information, try asking specific questions about relatives who seem to disappear or whose death records you can’t find where they should be. Utah genealogist Sarah Gibbons found out from her mother that her great-grandaunt was in a state hospital in Missouri.

Censuses: Examine census records carefully. The decennial federal censuses for 1840 through 1880 have a column denoting insane persons. A “tick” or hash mark indicates that the person was considered “insane.”

A person who was institutionalized when the census was conducted will be listed with others in that facility, with the facility’s name written across the top of the page. Gibbons found her aunt in the 1920 and 1930 censuses as a patient in State Hospital Number Four for the insane.

If you discover your relative resided in an institution, check the institutions’ first listing in the census. The names of employees are typically listed first in the institution’s enumeration, followed by inmates’ names (note that “inmate” was used for anyone in an institution, even children in orphanages). A word of caution: Census listings were likely compiled from the institutions’ admission records, not from talking with the inmates or residents. This will become especially clear if the names are in alphabetical order.

Some enumerations of prisons may state the crime committed by the individual. In the 1850 federal census for New York, for example, the inmates at the Auburn State Prison in Cayuga had been convicted of crimes such as larceny, burglary, rape, forgery and manslaughter.

The 1880 US census adds further detail, with columns labeled:

- Is the person (on the day of the enumerator’s visit) sick or temporarily disabled, so as to be unable to attend to ordinary business or duties? If so, what is the sickness or disability?

- blind

- deaf and dumb

- idiotic

- insane

- maimed, crippled, bedridden or otherwise disabled

If your ancestor’s listing has a mark in one of these columns, check the supplemental schedule of defective, dependent and delinquent classes, also called DDD schedules. DDD schedules, which exist only for the 1880 census, further detail circumstances surrounding the institutionalization. Separate schedules cover the “insane,” “idiots,” paupers in almshouses, those in jails or prisons, orphans and those who were blind, deaf or “mute.” You can search DDDs for many states on subscription site

Ancestry.com.

Other states’ schedules are sprinkled across various repositories. Don’t forget to also look for state censuses, as these may give different details.

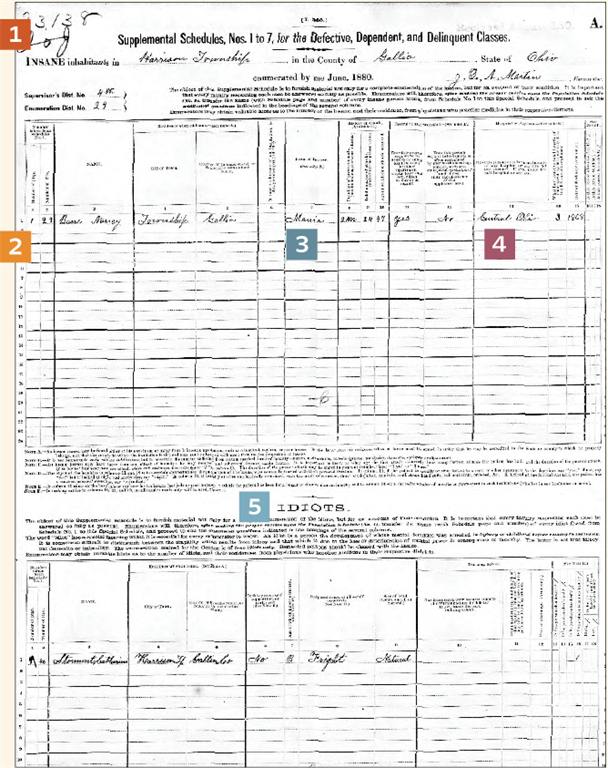

Record at a Glance: 1880 Schedule of Defective, Dependent and Delinquent Classes

1. The DDD schedules include separate listings for the “insane,” and “idiots.”

2. These numbers reference the page and line of the person’s listing on the 1880 population schedule.

3. The form of disease causing insanity (here, “mania”) or cause of idiocy (“fright”) is given.

4. You may find additional details about the infirmity, such as duration, age at onset, and whether the person has been institutionalized.

5. Enumerator instructions suggested census takers ask local physicians for names and addresses of locals fitting the definition of “idiot.”

Citation for this record: U.S. Federal Census 1880 Schedules of Defective, Dependent, and Delinquent Classes, Ohio, Gallia County, Harrison Township, enumeration district 29, sheet A, images online (Ancestry.com: http://ancestry.com : accessed 20 December 2014), citing National Archives microfilm T1159; Nonpopulation Census Schedules for Ohio, 1850-1880; Year: 1880; Roll: 99.

Death certificates: If an ancestor or relative died in an institution, this information should be recorded on the death certificate. The 1932 death certificate for Gibbons’ aunt gave her cause of death as “insanity” and her residence as “State Hospital #4.”

Cemetery and burial records: Many institutions had their own cemeteries. Unfortunately, graves are often unmarked, or marked only by a number, partly to protect the patient’s and family’s privacy and partly because funds weren’t available for markers. Further, burial records at institutions haven’t always been well maintained.

InstitutionalCemeteries.org provides information on known cemeteries of asylums, poorhouses, poor farms, prisons, orphanages and similar institutions, as well as links to user-submitted burial details on

Find A Grave.

Newspapers: Searching digitized newspapers for your ancestor’s name may reveal an article about a crime or a court news report stating she was committed (historical papers carried many news items that we’d consider an invasion of privacy today). Gibbons found a mention of her aunt in a local newspaper digitized at

Chronicling America. “

The Farmington Times had a column for court proceedings and warrants,” she says. “I was able to learn that my aunt’s warrant for examination and admittance into the state hospital both happened about January 1919.”

If your search comes up empty or the local papers you need aren’t digitized, browse microfilmed versions around the time of his disappearance.

Uncovering institutional records

Most institutional records are subject to privacy laws restricting records to the person only, or to immediate family if the person is deceased. Records of federal and state institutions may be released after a given number of years; private institutions’ policies vary. Records might have also been destroyed in the absence of official retention policies. Be prepared to provide ID and proof the person is deceased when you make a request. Archives might require a fee to have an archivist search for you.

Once you have the name of an institution, do an internet search on it plus history and records. If the institution is still open, contact it directly about your ancestor’s records. Even if it’s defunct, you may find online history and research tips. For example, Penhurst State School and Hospital outside of Philadelphia operated from 1908 to 1986. The

Penshurst Memorial and Preservation Alliance has history and photos, and the

Penshurst Project preserves stories of the staff, administrators and residents.

Next, find out what entity had jurisdiction over the institution: the federal government, a state, a county, a city, a church or a private organization. Then check repositories and agencies of that jurisdiction. For example, a state archive or family services department would most likely house records of a state orphanage. A local diocese or church archive might house records of an orphanage run by the church. For religious organizations, check state and local historical societies for records, as well as the administrative office where the orphanage was located.

A locator at can help you find Catholic dioceses.

But records also might be in the Family History Library or in university or public libraries. On FamilySearch.org, run a Place search of the online catalog and look under the subject headings Archives and Libraries, Correctional Institutions, Court Records, Guardianship, Medical Records, Military Records, Orphans and Orphanages, Probate Records, and Schools. Use links in the catalog listing to rent promising microfilm for viewing at a local FamilySearch Center. Search online with the place and a keyword describing the type of institution or its name.

Online institutional records are relatively few, but genealogy websites may have databases and images. In

Ancestry.com’s online catalog, search for the state and the type of institution in the Keyword field. Collections may not be titled intuitively, so try a variety of keywords. For example, search for prisons with the term penitentiary, prison, convict or corrections. For insane asylums, enter state hospital, institution or medical. Also try the name of the institution or browse the categories under Filter by Collection.

Learning more

The information and records you may find depend on the type of institution your relative was in. The following specifics will aid your search:

State hospitals, insane asylums and sanatariums: A good number of those committed to state hospitals and insane asylums were totally sane. Women were especially vulnerable to being “put away” for conditions such as depression, anxiety or even infidelity. A husband who wanted his wife out of the picture may have found commitment a viable solution. For example, if he wanted to sell land but his wife wouldn’t release her dower, he could try to have her declared insane and incompetent.

Sufferers of tuberculosis (also known as consumption), a common illness in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, may have been confined to one of the many tuberculosis sanatariums around the country. The Campaign Against Tuberculosis in the United States by Philip P. Jacobs (available on Google Books) includes a directory of institutions in the United States and Canada.

Registers usually include the patient’s name, age, birth date and place, date of admission, date of discharge or death, and medical condition. Start your search with state or county archives or historical societies, depending whether the institution in question was state- or county-run. Search the organization’s catalog or contact an archivist and ask about records and any restrictions.

Court records are key to gaining more information on patients. Look in the probate or surrogate’s court records for commitment proceedings, as these are often open to the public and may have details on the patient’s illness, with testimony from doctors and family. See our Probate Records Workbook in the September 2014 Family Tree Magazine.

Prisons: To house those outside the law, the federal government, states and counties built thousands of prisons, correctional facilities, jails, reformatories and penitentiaries, some of which still exist. If your ancestor or relative wasn’t a law-abiding citizen, you may hit pay dirt: Crimes are usually of public record.

Penal records can give the usual information—name, age and birth date and place—but also a physical description, sometimes a photograph, educational details, substance use, information on parents and/or children’s, religion, occupation and nationality. You’ll also find information on the crime, date of incarceration, court where charged, and if and when discharged. Add to that the possibility of finding prison hospital records, death warrants, clemency files, pardon books, executions, burials (if there’s a cemetery on prison grounds) and more.

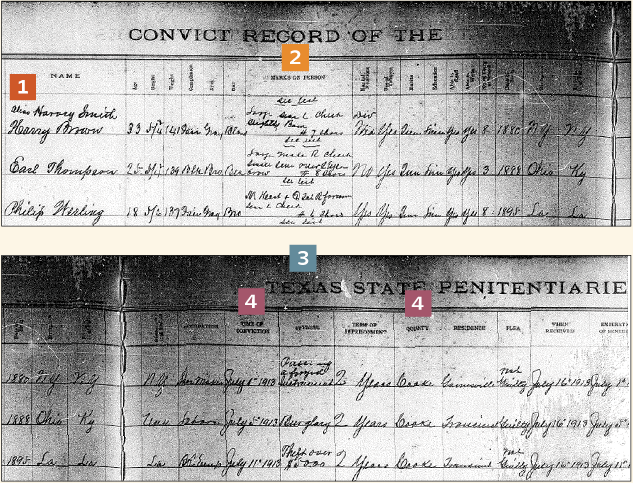

Record at a Glance: Convict Ledger

1. Expand your name searches to include any aliases.

2. A detailed physical description—including identifying marks—would help authorities identify the person in the future.

3. The custodial archive may provide help understanding the record. The Texas State Library and Archive Commission lists common abbreviations in convict registers.

4. The date of conviction and county of residence can help you find trial records.

Citation for this record: Conduct Registers Vol. 1998/038-158, microfilm reel 6 (Huntsville, 1911-1915), page 151 (July 1913), Texas Department of Criminal Justice, Archives and Information Services Division, Texas State Library and Archives Commission, Austin, Texas.

Poorhouses: Depending on the time and place, an institution for the poor can be called an almshouse, poorhouse, poor farm or house of refuge. Elderly residents might be placed in an old age, veterans’ or soldiers’ home.

As for medical institutions, paperwork may be limited to admission registers that include the person’s name, age, sex, race, any illness, and dates of admission and discharge or death. If you’re lucky, records might include more details, such as occupation before admittance, literacy and the reason for coming to the facility.

For state-by-state listings of poor houses, visit

PoorHouseStory.com (this volunteer-run website isn’t comprehensive). State and local archives may have records and even online indexes or images. One example is the

Tewksbury, Mass., Almshouse Intake Records (1854-1884), a collection of handwritten interviews with inmates upon admittance. These and other poorhouse records are also available on microfilm at the FHL.

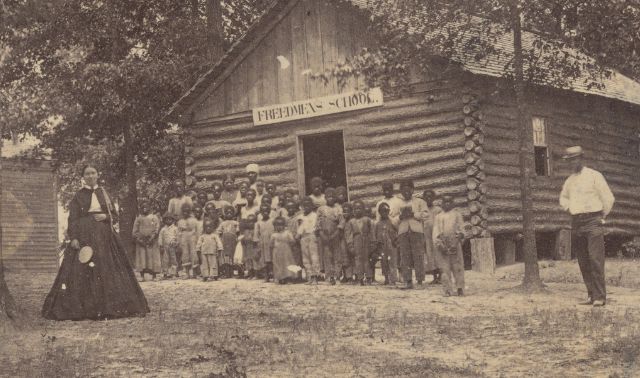

Orphanages: In colonial times, citizens were appointed or elected to be overseers of orphaned children. Children might be bound out to learn a trade or placed in an orphanage if they were too young. Court records and minutes might document these events; look in indexes under paupers, orphans or apprentices. Eventually, churches (especially the Catholic Church) and state and local governments took over the responsibility for orphans.

Read more history at FAQS.org.

You may find admission registers with the name of the child, age, birthplace, admission date, names of parents or other relatives, discharge date, and details on adoption or indenture. Also research records of the local probate or surrogate court, which handled guardianship cases.

Keep in mind that some institutions overlapped purposes: For example, an orphan could have been placed in a poor house or an orphanage. The elderly could reside in an old age home, veterans’ home or poorhouse. Someone with tuberculosis could be in a sanatorium or a hospital. A mentally ill patient could be in a state hospital, an insane asylum or a poorhouse. Your ancestor’s institutionalization potentially generated many records, but finding them takes patience and diligence. In the end, you’ll gain a greater understanding and appreciation of what your less-fortunate ancestors endured.

Tip: Many abandoned institutions have a reputation for being haunted. Sensational though they may be, don’t overlook websites about paranormal investigations, which may have interviews with former residents and employees.

Fast Facts

- Earliest Institutions: The first almshouse in America opened in Philadelphia in 1728. The first orphanage opened in 1729 in New Orleans. The earliest state hospital, Eastern State Hospital in Williamsburg, Va., opened in 1773. The federal prison system was established in 1891.

- Where records are kept: If the institution is still in operation, check there for records. If not search online for information and contact repositories of the entity with jurisdiction over the institution. Also check the FHL catalog, government archives, historical societies, university and local public libraries and genealogy websites.

- Search terms: The city, county, and state plus the name of the institution and/or words such as history, asylum, orphanage, poorhouse, etc.

- How to find in the FamilySearch catalog: Run a place search and look under the subject headings Archives and Libraries; Correctional institutions; Court Records; Guardianship; Medical Records; Military Records; Orphans and Orphanages; Probate Records; Schools

- Alternate and substitute records: Probate or surrogate’s court records, court minutes, census, death records, newspapers, military records (for crimes while enlisted)

Publications and Resources

- Annie’s Ghosts: A Journey Into a Family Secret by Steve Luxenberg (Hachette)

- The Campaign Against Tuberculosis in the United States, Including A Directory of Institutions Dealing with Tuberculosis in the United States and Canada by Philip P. Jacobs (Charities Publication Committee)

- “The ‘Forgotten’ Census of 1880: Defective, Dependent, and Delinquent Classes” by Ruth Land Hatten (March 1992 National Genealogical Society Quarterly)

- Forgotten Ellis Island: The Extraordinary Story of America’s Immigrant Hospital by Lorie Conway (Smithsonian)

- Living in the Shadow of Death: Tuberculosis and the Social Experience of Illness in American History by Sheila Rothman (Basic Books)

- “Mania and Nancy Bane: Identifying the Family of Nancy (Donnally) Bane, Inmate at the Central Ohio Lunatic Asylum and the Athens Insane Asylum,” by Sharon DeBartolo Carmack (Jan-Apr 2004 The American Genealogist)

- Women of the Asylum: Voices from Behind the Walls, 1840-1945 by Jeffrey Geller and Maxine Harris (Anchor Books)

Quiz

1. Where would you look for evidence of your ancestor being in an institution, such as a state hospital or insane asylum?

a. family stories

b. censuses

c. probate records

d. all of the above

2. If you’re looking for institutional records and do a place search of the FamilySearch catalog, which of these subject headings would you look under?

a. migration

b. tax records

c. archives and libraries

d. heraldry

3. Other names for poorhouses were:

a. almshouse

b. poor farm

c. house of refuge

d. all of the above

Exercise A: Go to Ancestry.com and search the 1850 census for David Molay in Auburn Prison, Cayuga County, NY.

1. What was David’s crime?

2. Where was David born?

3. What was David’s occupation?

4. Where would you look next for more information on his crime?

5. Write a citation for this record.

Exercise B: Review death records of your ancestors and their siblings to see if any died from tuberculosis. Then look for The Campaign Against Tuberculosis in the United States, Including A Directory of Institutions Dealing with Tuberculosis in the United States and Canada in Google Books. Review the institutions in your ancestor’s state. List possible institutions to check for records. (Keep in mind that people might travel to out-of-state institutions for treatment.)

Exercise C: Review the 1880 census for all of your ancestors who were recorded then. Look carefully at the columns with questions regarding health. Did you overlook any hash marks in those columns for someone?

Answers: 1. d 2. c 3. d Exercise A: 1. Pt. (petty) larceny 2. Scotland 3. Tool maker 4. Newspaper and court records 5. 1850 U.S. population schedule, New York, Cayuga Co., Auburn Prison, p. 316, images online, Ancestry.com (http://ancestry.com: accessed 14 April 2015).

More Online

From the January/February 2016 Family Tree Magazine