Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

A birth date is one of the most basic facts about an ancestor’s life. Yet determining the correct one can prove quite the challenge for genealogists.

Dates of death are literally carved in stone, and marriage dates have been recorded by churches for hundreds of years. Both regularly appeared in newspapers as obituaries and marriage announcements, respectively.

But birth dates are more likely to be a mystery—perhaps even to the individual him- or herself. People may simply have relied on what they were told by parents and other relatives, particularly before the adoption of government-issued vital records. Some localities kept records as early as the 1600s, but many states didn’t adopt mandatory registration until the late 19th (or even early 20th) century.

The result is a wide variety of records (created throughout a person’s life) that can provide birth information, with each document possibly reporting a different birth date. How do you discern which is correct?

There isn’t a straightforward answer, and you’ll need to carefully evaluate each record. While you might not be able to determine an exact birth date, examining records will hopefully provide at least a range of time.

In this article, I’ll share five questions you should ask yourself when comparing birth dates across records. I’ll also share a case study from my own research, in which I sifted through six different birth dates for an ancestor to determine which was the most accurate.

1. When Were the Records Created?

You can’t guarantee that one type of record will always be accurate. But, in general, details in records are more reliable when the record was created close in time to the event being documented. People remember events more clearly when they’re fresh in their minds, so give greater weight to records that were created soon after your ancestor’s birth. Family Bibles or baptismal records, often created close to an infant’s birth, are thus good sources in the absence of an actual birth certificate.

2. Who Were the Sources of Birth Information?

Records are only as accurate as the information given to the record-keeper, so consider who the informant was. This isn’t always possible; early censuses, for example, didn’t list who in the household provided information. But many records did require at least the mark of an informant.

Figure out what relationship—if any—the informant had with your subject. Immediate family members (especially parents) or others plausibly present at the birth like grandparents or aunts/uncles are more reliable witnesses to birth information than a distant cousin, child, or total stranger. Also consider if the informant was old enough to have witnessed and accurately remember the event they’re reporting on. A local physician or midwife who attended the birth may have kept records of it, though these accounts are unusual.

3. Can I Corroborate the Date With Other Sources?

Do several records point to the same date, or does one record’s date contradict other documentation? If a new record you found disagrees with several other, reliable sources, you might have reason to doubt the new record’s accuracy. Other records might have omitted birth information if the informants weren’t certain of those details.

4. Is This Birth Date Plausible?

Certain conditions had to be ripe for a birth to take place. As such, you should consider the statuses of other family members on the supposed birth date. For example, on the birth date:

- The mother had to be alive

- The mother had to be of reproductive age (say, between the ages of 14 and 45)

- The father had to be alive and of reproductive age (i.e., at least 14 or 15 years old) nine months before the birth

- The father and mother had to be in the same geographic location nine months before the birth

- Any siblings born to the mother had to be at least nine months older or younger than the subject, unless the child was a twin, triplet, etc.

Also determine if you’ve located records that document the subject before they were supposedly born (for example, appearing on the 1850 federal census but having a reported birth date in 1851). That would also suggest the birth date is not possible.

Birth order plays a role, too. If you already know the subject’s siblings were older or younger, the subject should have been born in the correct sequence relative to the siblings.

5. Is There a Reason the Source Would Be Dishonest?

Then as now, people in your ancestor’s time might have had reason to lie about their age. Men may have lied to enter (or avoid) military service, or parents adjusted a child’s birth date to cover him or her being born or conceived outside of marriage. Or maybe a woman fibbed about her age to so she appeared younger than her husband.

Others may have lied about theirs or someone else’s age for more disreputable reasons. An informant might pretend to have valuable information about someone to demonstrate a relationship with them, or lie about their own life events to get a cut of someone’s inheritance.

Case Study: The Many Birth Dates of Thomas H. Higgins

My ancestor Thomas H. Higgins left behind records that reported at least six different birth dates. The following describes how I determined which was the most likely, and what criteria I used to evaluate the various records.

My research began with a nine-page biography written by my grandfather, which included copies of original records. According to the biography, Thomas’ parents (James R. Higgins and Margaret Mousley) married 5 April 1855 and had a total of three children, of whom Thomas was the eldest.

Other facts from Thomas’ biography caught my eye and led me to more records, including:

- James died in the Second Battle of Bull Run (August 1862). Margaret, now a widow, applied for a pension.

- Thomas attended Girard College in Philadelphia

- Thomas enlisted in the US military during World War I. Based on available information, he would have been in his 60s at the time—well over the maximum age of enlistment. He presumably lied about his age.

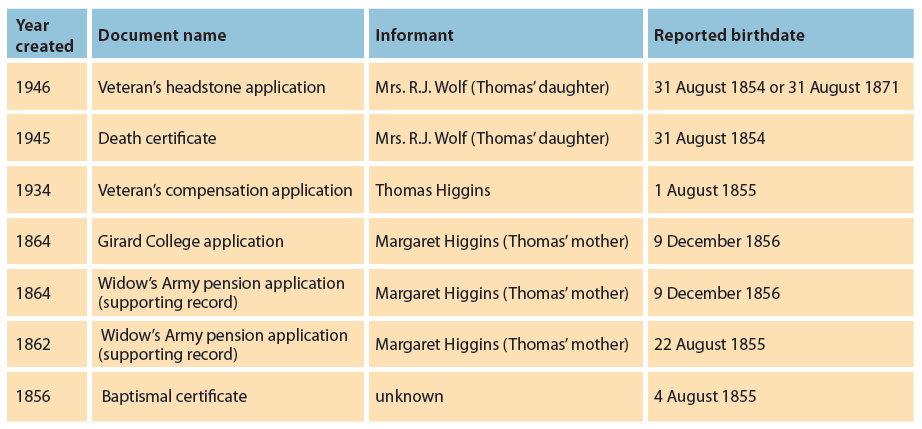

Both Margaret’s Widow Army pension application (from the National Archives) and Thomas’ application to Girard College (from the school itself) establish his birth date as 9 December 1856.

But as I researched more deeply, other records presented different dates and cast the December birthday into doubt. Thomas’ marriage records, created in 1880 and 1891, give only his age, but I reverse-engineered his birth date based on his age in each year and found it must have been earlier than December 1856. The 1900 federal census—which asked for birth month in addition to age—was another dissenter, reporting a birth month of August 1855.

From there, evidence for the August 1855 date began piling up. On a veteran’s compensation application, Thomas gave his birth date as 1 August 1855. Thomas had lied about his age before, so I thought he perhaps did so here as well. But upon further review, I realized some of the records in Margaret’s pension application provided conflicting birth dates for all three of her children. One document had Thomas’ birth date as 9 December 1856, but another had it as 22 August 1855. Another critical document, Thomas’ baptismal certificate, offered 4 August 1855.

Subsequent research into Thomas’ death certificate and an application for a veteran’s headstone corroborated August as his birth month, but gave a different day and year: 31 August 1854. The latter record was made even more confusing because someone crossed out 1854 and scribbled in 71—were they suggesting Thomas was born on 31 August 1871?

What to do? With all this conflicting information, I resolved to look at each source in turn, considering when and how it was created as well as how reliable it was for other details.

Here the records are in reverse order of age:

Veteran’s Headstone Application

Thomas’ daughter, Ruth (“Mrs. R.J.”) Wolf, applied for a special veteran’s headstone for Thomas in February 1946, a few months after Thomas’ death. The birth date Ruth provided initially matched the one she supplied for her father’s death certificate (31 August 1854), but someone seemingly changed it to 31 August 1871.

Applications for these headstones were likely checked against military service records—which may have had falsified birth information for Thomas. By reporting a later birth year (say, 1871) on military documents, Thomas would have presented himself as younger and thus been able to enlist in World War I. The record-keeper changed the date from 1854 to 1871 to make it consistent with existing military documents, but ultimately reinforced Thomas’ lie from decades earlier.

I could also disregard the 1871 date for two other reasons: Thomas’ father died nine years earlier in 1862, and I had other documentation of Thomas in the intervening years.

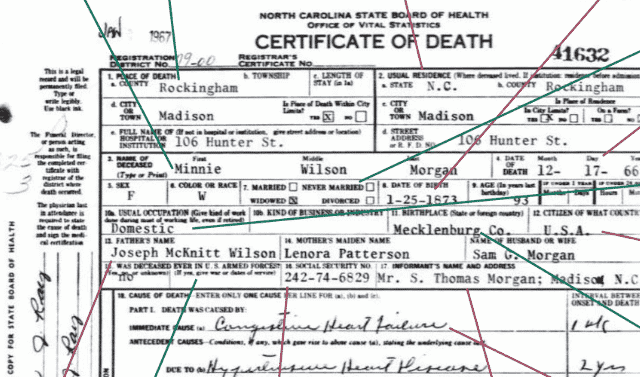

Death Certificate

As previously mentioned, Thomas’ daughter Ruth was the informant for his 1945 death certificate, in which she noted his birth date as 31 August 1854. Ruth was something of an unreliable witness for his birth; as Thomas’ daughter, she couldn’t have had firsthand knowledge. She was also incorrect on at least one other key piece of information about Thomas: She identifies his father as an Isaac Higgins.

Furthermore, the 1854 birth year was earlier than reported in any other record I located—and earlier than his parents’ documented marriage in 1855. It’s likely that Ruth incorrectly remembered or miscalculated Thomas’ birth year based on his age when completing these records.

Veteran’s Compensation Application

In 1934, Thomas applied for benefits stemming from his service in World War I, and reported his birth date as 1 August 1855. That choice is an interesting one; I’d already established he enlisted with a fake birth year of 1871, so that date shouldn’t match the one in his service records. But this document doesn’t show any correction. Perhaps, given the many years that had passed, Thomas didn’t remember the 1871 birth year he reported when he enlisted, and so provided what he honestly believe was his birth date.

Girard College Application

In April 1864, Thomas was admitted into Girard College in Philadelphia. According to A Brief History of Girard College, the school was established for “poor white male orphans.” The college became the legal guardian of the boys who attended the school, and was a desirable prospect for Thomas because it offered him educational opportunities he likely wouldn’t have had elsewhere, as well as room and board.

To enroll him at Girard, Margaret (Thomas’ mother) needed to firmly establish that James Higgins was Thomas’ father and that he was deceased. On the application, she reported Thomas’ birth date as 9 December 1856. To erase any doubt about the identity of Thomas’ father, perhaps that date was a fib. With an August 1855 birth date, Thomas was born only a few months after his parents’ marriage. A December 1856 birth date (20 months after James and Margaret’s marriage) would have been more socially acceptable, and laid to rest any possible questions about Thomas’ paternity.

Widow’s Pension Application

Next we come to Margaret’s pension application, which included several supporting documents—some of which were, as we’ll see, in disagreement about certain dates.

One of the records was created on 22 March 1864, and listed Margaret’s children as having the following birth dates:

- Thomas: 9 December 1856

- Sarah Elizabeth: 1 December 1858

- Anna Mary: 16 April 1860

But another document, created in September 1862, lists the children’s birth dates as:

- Thomas: 22 August 1855

- Sarah E(lizabeth): 2 December 1857

- Anna Mary: 16 March 1861

Margaret was the informant on both records, as indicated by the X by her name. I considered how accurate the records were for other information. Based on other research, I identified at least two errors in the 1862 record:

- Anna Mary could not have been born in 1861 because she was listed as an infant in the 1860 census.

- James’ death date is given as 9 August 1862, but the Second Battle of Bull Run (in which James was killed) didn’t take place until later that month. Military records have his death date as 30 August.

By contrast, I didn’t find any documents that contradicted the 1864 record (except for Thomas’ disputed birth date). The 1856 birth date for Thomas, reported in that record, is certainly plausible: Both of his parents were alive, in their mid-20s, and married both at time of conception and birth.

But that may have been by design. As in Thomas’ application to Girard, Margaret needed to establish, without doubt, that James was Thomas’ father. Otherwise, she wouldn’t be eligible for benefits. Admitting that Thomas was born in August 1855, just four months after her marriage, may have left her open to uncertainty about Thomas’ paternity.

Baptismal Record

The gold standard of birth record substitutes: the baptism certificate. Thomas’, dated March 1856, presents his birth date as 4 August 1855. As the earliest record of Thomas that I’ve found, the baptism certificate carries a particular weight. If the certificate is correct, it would obviously preclude a December 1856 birth date.

But it’s not foolproof. The certificate doesn’t name an informant, and it lists Thomas’ father as a Thomas Higgins (contradicting all other sources).

Conclusion

The balance of evidence suggests that Thomas Higgins was born sometime in August 1855. The earliest records mentioning Thomas’ birth—his baptism certificate and a record from Margaret’s pension application—support a birth date in that month, though I can’t yet establish an exact date among the competing options.

The 1854 date came from much later documents and a single informant (Thomas’ daughter) who didn’t have first-hand knowledge of Thomas’ birth. And I could dismiss the 1871 date out of hand, given the various documentation I had of Thomas before that year.

The other leading candidate, 9 December 1856, only appeared later, in 1864. Margaret, as Thomas’ mother, would have had first-hand knowledge of his birth. But she only reported the 1856 date when she had a motive to be dishonest, likely to hide the fact that Thomas was born only four months after her marriage. The incorrect 1856 was then picked up in the biography my grandfather wrote.

Tip: Though most US federal censuses only reported ages, you can reverse-engineer birth dates using them. For example, a 25-year-old in the 1870 census (taken on 1 June 1870) was likely born between 2 June 1844 and 1 June 1845. Compare these dates across censuses to hone in on a specific birth date.

Related Reads

A version of this article appeared in the July/August 2022 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: July 2025