2025 marks the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II. That milestone underscores how precious eyewitness accounts of that era are.

But for many survivors—notably, those of the Holocaust or of wartime bombing raids—the resulting trauma has created a “veil of silence.” Their descendants crave understanding and healing, yet survivor’s guilt and a desire to leave the past behind can keep people from talking.

Others may feel shy for different reasons. Some believe their life has been unremarkable or worry about how they will sound.

I recently worked with Heidi Posnien, who lived in Berlin throughout the Second World War. Together, we published her memories in a book called A Child in Berlin (Post Hill Press; also available here).

In a radio interview on a local National Public Radio affiliate’s “All Things Considered,” Heidi said, “It’s very hard for me to talk about the past like that because it brings back memories. It took us five years to write this book. It wasn’t easy.”

Despite the pressure of being on the radio, Heidi told one of the most-harrowing experiences of her life. When she was 9 years old, she couldn’t make it to a shelter during a bombing raid. She was alone in an apartment with the windows and doors blasted out—and watched her neighbor’s home burn.

“You could see the fire in the back, and it was all lit up … It was cold, and glass was all over my bed,” she says. “Then it all burned down, and I curled up and cried myself to sleep.”

How did the radio interviewer, Pamela McCall, help Heidi open up in such a high-pressure studio environment? And how did Heidi and I work through all those emotionally charged memories when working on the book?

This article provides practical guidance for sensitively conducting oral history interviews with people who have experienced war, grief or other trauma. It draws on best practices from professional journalists, plus my years as a biographer hearing people’s regrets, deeply spiritual experiences, and heartbreaks.

We’ll also touch on special considerations for end-of-life storytelling, and concrete ways of making your interview subject feel more comfortable.

1. Prepare Questions

Great interviews start with great questions. Before you begin yours, ask the person if they have topics they want to cover. You might seek input from other family members, including to see what experiences they already know about.

Then, provide a list of questions beforehand so your subject can prepare. As a rule, create narrow, specific prompts. Avoid broad questions like “Tell me about the war.” That’s too big of a topic. Instead, do some homework and ask about specifics:

- Where did you go during air raids?

- What do you remember about rationing?

- How did your parents talk to you about the event?

I have a free collection of prompts on my website.

Your questions need not be complex. The late, great Larry King had a deceptively simple favorite question: Why?

“I love asking questions. I’ve been doing it all my life,” King said in a 2013 interview with the “Today” show. “When I was 9 years old, I asked the bus driver, ‘Why do you want to drive a bus?’ And I’m still doing that. Why do you want to drive a bus?”

When you sit down for the interview, begin with some warmup topics. People typically enjoy reminiscing about their hometown—a safer topic than home life or wider events, which can be emotionally fraught. Other icebreakers include asking how they met a spouse or chose their profession.

2. Set a Timer, but Go with the Flow

The most-powerful stories usually emerge in the second half of an interview. For this reason, it helps to set a timer and take a break at the halfway point. Stretch, get a drink, and visit the restroom.

Upon return, you will be amazed by how your subject has relaxed. Pausing can also help redirect the discussion if it has veered off course.

Few interviews will unfold according to your plan, so be flexible. The best moments often happen around unexpected topics. Let your subject speak freely, and ask spontaneous follow-up questions.

3. Learn What Not to Do

Rachel Trotter is a journalist who turned to life-story-writing and now has done over a thousand interviews. She recommends engaging in small talk before the recording starts—and avoiding yes/no questions.

She has also learned to tread lightly around certain topics. For example, Trotter says, “We used to have a question in our booklet about who was the love of your life, but that can be complicated and uncomfortable.”

Establish (and respect) boundaries

Trotter also advises inquiring in advance if they have any “off-limits” topics. Then, respect people’s boundaries, and turn off the recorder if someone requests. Occasionally, a client will want to cut part of an interview afterward, and you should honor their wishes.

A person’s story should belong to them. An oral history is not a tabloid piece, and not everything is meant for public consumption.

Keep yourself out of it

In addition, don’t make yourself the focus of the interview. Resist the temptation to interject how you can relate to what they say. That would be natural in the give-and-take of regular conversation, but inappropriate during oral history.

Instead, Trotter recommends that you jot down a reminder and save your comments for after the recording ends. “You never want to bring the conversation around to you,” she says.

Larry King had similar thoughts. “I never involved me in it. I always asked the questions of the guests. I never used the word, ‘I,’” he says. “My no. 1 motto: ‘I never learned anything when I was talking.’”

In an extreme example, politicians were banned from giving speeches at the 80th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz in 2025. Too often, politicians can’t help but make a speech to serve their agendas. Thus, event organizers rightfully focused on the victims.

In fact, consider having someone else conduct the interview altogether. There are drawbacks to an interviewer having an existing close relationship with the subject. Loved ones might assume the interviewer has already heard something and leave out important details. Or they may censor information in a way they wouldn’t with a third-party.

Finally, do not respond to someone’s suffering with platitudes or advice. Sometimes, there isn’t an upside, and there is nothing to be done but be with them. Don’t fill the silence—listening is enough.

Summary: The do’s and don’ts of family interviews

Do

- Prepare and share specific questions ahead of time

- Establish “off-limit” topics

- Start with safe icebreakers

- Ask follow-up questions

- Start today—tomorrow might be too late

- Embrace awkward silences or big emotions

Don’t

- Ask questions that are too general

- Ask questions that have a simple yes-or-no answer

- Make the conversation about you

- Try to interject, offer advice, or console

- Take it personally if a subject declines an interview

4. Create a Comfortable Environment

The ideal setting for an interview is your subject’s home. This is frequently impractical, so hosting the interview on Zoom or another videoconferencing service can be an effective alternative. In such cases, your goal is to make the person forget about the technology. Listen intently, which will help them focus on you and feel seen and validated.

For in-person interviews, I generally avoid recording the subject on video. People at the end of life may feel self-conscious on camera, and the dynamic can be even more difficult in the likely event you don’t have another set of hands to manage the tech while you’re trying to ask questions and listen to answers. Video has its place, but do not expect to capture intimate or traumatic stories in a short video interview.

5. Handle Declines Gracefully

It can feel like a rejection if someone declines your request to be interviewed. Don’t take it personally.

Instead, gently ask their reasons and listen for subtext. Tell them what it would mean to you and to future generations. Reassure them that they will not sound “dumb.” Explore whether they would allow a professional to conduct the interview.

Be compassionate if someone cannot talk about their trauma. Rozalie Jerome, State Director for the March of Remembrance in Texas and cofounder of the Holocaust Remembrance Association says, “I compare it to a plane that relies on much of its fuel to take off. Survivors need to ration their energy and mental focus so they can build a safe and successful future.”

For many of these families, telling the story will fall to the next generations. “Breaking the veil of silence is extremely healing,” Jerome says. “It’s cathartic. Being a descendant of Holocaust survivors is in my DNA and it helps me to understand myself.”

Finally, check back with the person occasionally because they may become ready as they enter their later years. This was the case for Heidi Posnien, who warmed to the idea in her eighties.

6. Listen Empathetically

The most important skill for any interviewer is emotional intelligence. You should be comfortable when another sheds tears, and know how to embrace silence.

One way to grow is by expanding your emotional vocabulary. Researchers have discovered that learning to simply name distinct emotions can help you navigate them. For help, check out Brené Brown’s Atlas of the Heart: Mapping Meaningful Connection and the Language of Human Experience (Random House). It’s an encyclopedia and field guide to understanding 87 different emotions—a skill you can develop.

Another skill is intensive listening. In his book, How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen (Random House), David Brooks writes, “People long for someone to look into their eyes with loving acceptance.”

He further explains that a person’s life should not be judged by heroic deeds. Instead, “Morality is mostly about the small, daily acts of building connection—the gaze that says ‘I respect you,’ the question that says ‘I’m curious about you,’ the conversation that says, ‘We’re in this together.’”

Pay attention to your own emotions, too. Give yourself time to decompress and recharge after an interview. Heavy conversations can take more energy than you expect! Self-care by getting outside, drinking some water, or taking a bath. If you find an interview has been an emotional trigger for you, get in touch with a therapist or friend, or process your feelings in a journal.

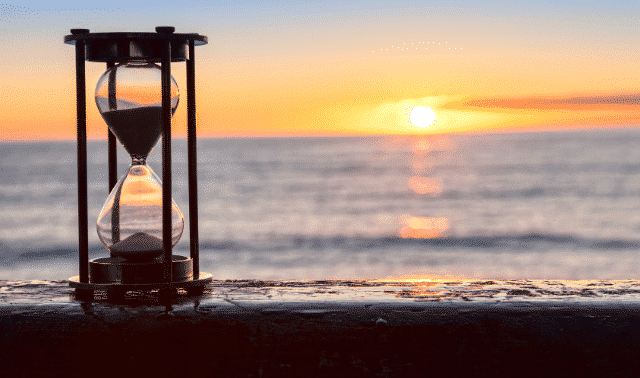

7. Honor the End-of-Life Journey

Hearing a person’s story at the end of life presents special opportunities and challenges. You may help a person unburden so they can leave this life peacefully. Capturing their story will help them know they will be remembered.

Laurrana Leigon spent her career as a hospice bereavement coordinator, supporting people during their last phase of life. Leigon has heard many dying wishes and regrets. She often went beyond listening to facilitate solutions so they could transition in peace.

She offers sage advice for such times:

“The most important thing is to carry the mindset that this is a sacred space. I don’t mean that in religious terms, I mean that it’s a delicate time and should be oriented toward the person who is transitioning. Your job is to be fully present in a way that is centered around them. It doesn’t mean you ignore your own needs, but that’s not the time.”

She encourages caregivers to ask the person to share their needs as they occur, whatever they are.

Conclusion: Act Now!

Families sometimes wait too long to interview a loved one only to have dementia or a rapid decline in health rob them of time. If you feel inspired to interview someone, reach out right away. You will be so glad you did.

Related Reads

A version of this article appeared in the May/June 2025 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

FamilyTreeMagazine.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com and affiliated websites.