Whenever I think about writing my family history, I get a craving for lasagne. Doesn’t everyone? I think it’s because writing family history is so similar to making lasagne. Here’s what I mean: When I decide to make lasagne, my first step is to go to the store and gather ingredients like Italian sausage, ground meat, garlic, a jar of Ragu and lasagne noodles. The next step is to prepare and layer the ingredients in the pan. The final step is baking, where all the flavors blend and the aroma in the kitchen can’t be beat. That’s what I proudly serve my family

Writing your family history follows the same three-step recipe and is just as important as feeding your family — after all, you’re feeding the curiosity of family members and future generations about where you came from. First, you head to the library, courthouse or archives to gather ingredients like censuses, vital records, land deeds, wills and background histories. Then you analyze and organize your research in preparation for writing. The final step, baking — I mean writing — is where you blend all the research ingredients into an interesting family history account, one that you proudly serve to your family.

But, as with making lasagne, there are some decisions you need to make. Do you want to make your lasagne vegetarian, traditional or a blend of cheeses only? Likewise, what kind of family history do you want to serve to your family? Let’s look at your options.

Making a plan

Start by deciding on the scope of your book. What will you include and what will you leave for another book? Will you cover one branch of your family or will it be an “all my ancestors” book?

Your book doesn’t have to be a tome. The first family history I wrote, The Ebetino and Vallarelli Family History, contained only 112 pages (8½×11 format), including the index. The one I’m working on now probably won’t be longer than 75 pages in a 6×9 format. It can be far better and more efficient to write a smaller family history; the project won’t be nearly as overwhelming and your goal is more attainable.

You should also decide on the audience for your family history: Who are you writing for? Most genealogists immediately think that their relatives will be their only audience, so they write their book with just family in mind. Think again. After all, in the course of your own research you’ve no doubt used others’ published family histories. So, besides your family, other genealogists will be part of your audience, especially if you donate a copy of your family history to a library. Social historians may also use your book as a springboard for their own research; many social histories cite published family histories among their sources.

Knowing that other researchers — genealogists and historians — might read and use your family history might change the way you write your family history. If you’re writing solely for family members, your inclination might be to skip footnotes, endnotes or other documentation, thinking that your family won’t care where you got your information. But even family members may want to pick up where you left off or take one of the branches further, which means they’d want you to include your sources.

I could go on and on about the reasons for citing your sources, but suffice it to say it’s like brushing your teeth: Make it a habit, and just do it. Citing sources is not an option when writing a nonfiction family history. After all, you’ve put a lot of work and effort into researching and writing your family history. Think of citing your sources as a way to show off your research and impress your family and fellow researchers! Without source citations, other researchers will use your efforts as clues only.

To make source citations less intrusive for the reader, use endnotes instead of footnotes. For more on this topic, see Elizabeth Shown Mills’ Evidence! Citation & Analysis for the Family Historian (Genealogical Publishing Co.).

Pick your genre: Seven possibilities

Next you need to consider the type of family history you plan to tackle. You can think of the options as seven genres of genealogical writing (see opposite page for examples of each):

1. Reference Genealogy: This is a typical “bare bones” genealogy of the sort you’ve surely seen in the course of your research. It covers mostly the facts about ancestors: names, dates and places. This type of genealogy is not meant to be read; it’s a reference book. There is little, if any, biographical material. The reader looks up an ancestor, gets the information, then moves on. Many genealogists simply print out their computer data and publish it, and a number of genealogy software programs will even create a “narrative” for you (see “Getting with the Program” in the June 2000 Family Tree Magazine). A good genealogy in this genre is fully documented and uses a standard numbering system, such as the Register or NGSQ system. For more on numbering systems, see Patricia Law Hatcher’s Producing a Quality Family History (Ancestry).

2. Technical Genealogical Narrative: This takes the “bare bones” reference genealogy a step further. In this category are genealogies that include biographical material, case studies, discussion of research analysis and your methods of research, with the main focus being the research and analysis. This genre is typically written in an academic style, incorporates full documentation, a standard numbering system, and seems to aim for an audience of other researchers, rather than family members. An excellent guidebook for this genre is Hatcher’s Producing a Quality Family History.

3. Life Story Writing: Biographies, memoirs and autobiographies fall under this category, as well as “folksy,” self-published family histories and memoirs. The self-published ones usually contain a lot of biographical or autobiographical material and family stories, but the information, unfortunately, is generally undocumented and relies on little outside research beyond someone’s memory. Pedigree charts and family group sheets are typically included. A well-done life story is Frank McCourt’s best-selling Angela’s Ashes: A Memoir (Simon & Schuster).

4. Family History Narrative: These are fully documented narratives that tell the story of a family; they’re examples of what’s called “creative,” “dramatic” or “literary” non-fiction writing. Written in third person, these stories focus on characters, setting and plot and read like a novel. Woven in with the facts about the family gleaned from genealogical research are family lore and social, oral, ethnic and women’s history. A combination of this genre and technical genealogical narrative makes the ideal family history book: The first half of the book is the family history narrative; the second half contains the technical genealogical narrative. A model example is Peter Haring Judd’s The Hatch and Brood of Time: Five Phelps Families in the Atlantic World, 1720-1880 (Newbury Street Press).

5. Family History Memoir: The better ones of this genre are documented. Like family history narratives, family history memoirs tell a nonfiction story, centered around the author’s search for his or her ancestors. It’s typically told as a first-person account. Excellent examples are mystery writer Mary Logue’s Halfway Home: A Granddaughter’s Biography (Minnesota Historical Society Press) and Edward Ball’s Slaves in the Family (Random House).

6. Genealogical Fiction: There’s nothing saying you can’t turn your genealogy into fiction. Alex Haley did it in Roots: The Saga of an American Family (Dell), and John Steinbeck’s East of Eden (The Penguin Group) was inspired by his family history research. Just be certain to inform your readers in the introduction that this is a work of fiction based on fact. Being fiction, this type of writing is not documented; however, some historical/genealogical fiction writers add an author’s note with the sources they consulted.

7. Edited Letters and Diaries: The final genre of genealogical writing is for those who have a large collection of an ancestor’s letters, diaries or other memorabilia. You could simply transcribe the documents and publish them, but the work will be much more valuable to a wider audience if you also annotate the documents, adding historical context and explaining information found in the documents. One example, edited by a historian and a genealogist, is Arch Fredric Blakey, Ann Smith Lainhart and Winston Bryant Stephens Jr.’s Rose Cottage Chronicles: Civil War Letters of the Bryant-Stephen Families of North Florida (University Press of Florida). The authors weave together family documents to tell the story of people’s lives.

Bringing the past to life on paper

Once you’ve made a plan and picked a genre, it’s time to start writing — and making your family history come to life so someone will want to read it. Remember, no family history is enthralling until you make it enthralling.

For many people, the actual writing is the really hard part of creating a family history. Writing need not scare you! I promise that your eighth-grade English teacher won’t come out of nowhere and bleed all over your prose with red ink. True, not everyone is born a writer, but nearly everyone is capable of learning how to write clearly and engagingly.

Just think of writing your family history as telling a story. All good stories have a beginning, middle and an end, and it’s these three parts that should get most of your attention:

1. Crabbing your readers: I don’t know who came up with the notion that a family history or life story had to begin with, “Cornelius McMasters was born on 17 October 1898 in a log cabin in Overton County, Tennessee.” Who’d want to read any further? Would you keep turning the pages of a novel that started on such a dull note? Whether you choose to write your family history as nonfiction or fiction, you can use the same writing technique that fiction writers often use: Start in the middle of a story, at the most dramatic and interesting point, then flashback and tell the reader how we got to that point.

If you’re writing about an immigrant family, you might begin the story aboard ship or the moment they first step foot on American soil. Or say you’re writing about a family who made the overland journey from east to west — open with what it must have been like on the trail. Reel the reader in with an exciting, happy or tragic event or a conflict. If you have letters, diaries or an interesting written record, you can open by quoting that source. (But remember: If you choose to write nonfiction, you can’t make up your opening for dramatic effect — it has to be built from facts.)

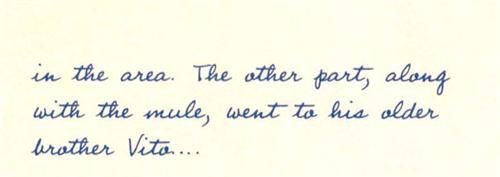

Here’s an opening example from a soon-to-be published Cannizzaro family history by Elaine Trigiani:

See how the author plunges us right into the middle of the story? Later she flashes back to fill us in and answer the questions raised in the opening.

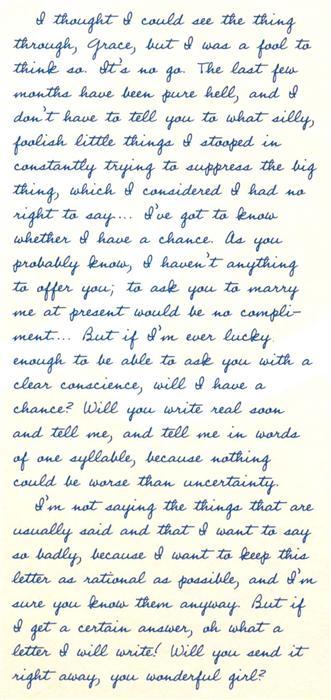

2. Keeping the story from sagging in the middle: How do fiction writers keep you turning the page? They build suspense. You don’t have to aim for Stephen King suspense — just leave something hanging, either within a chapter or at the end of a chapter. Don’t give readers everything you know all at once. Create an air of mystery. Here’s a quote from a letter that I used to end a chapter in a family history:

Now, be honest. Could you put the book down at that point? Even if you were late to pick up your kid from school, wouldn’t you turn the page for a peek at Grace’s answer?

3. Ending the story: So who says a family history has to end when everyone in the story died? Or that the story has to have a happy ending? You don’t have to kill off your ancestors if you don’t want to, nor does everyone have to live happily ever after. You can end the story with your great-grandparents in their old age. You can conclude with a tragic event; throughout literary history, tragedies stick with us longer and have more of an impact on us than “and they lived happily ever after.”

When I was writing the biographies of Jay Roscoe Rhoads and his wife Grace (soon to be published by Newbury Street Press), I didn’t want to kill off Roscoe and Grace at the end of the story. I’d grown fond of this couple, and I didn’t want to see their demise, even though in reality they’ve been dead for about 15 years. So I didn’t end their story with their obituaries. Instead, I put family stories of their last days in an epilogue, followed by something more haunting and enduring. Fortunately, Roscoe had written a fabulous two-page reminiscence on his 85th birthday, about two and a half years before he died. It contained his life’s philosophies and ended with a great closing sentence: “Well, so much for the ruminations of a tin-horn philosopher, just turned 85.” The end.

Make your documents work for the story, so they become powerful openings, middles or endings.

Getting into print

Typically, most family histories are self-published, and you can find plenty of printers and publishers that produce small print runs of books. Self-publishing means you pay for the entire publication, including marketing and distributing your book.

Most family histories are self-published because they have a limited audience appeal; the author writes the family history assuming only family will read and be interested in it. But did you notice that almost all of the examples were professionally published? In fact, two of these authors won a Pulitzer Prize, and a couple of them made the best-seller list. How did they do it, and how did they find a commercial publisher to foot the cost of producing their books? They wrote their family history so it had a wide audience appeal. If this is your goal, then avoid the reference or technical genealogical genres, and concentrate on writing your family history as a narrative story about people.

For more resources on writing techniques and getting professionally published, see Writer’s Digest magazine <www.writersdigest.com>.

Now the guilt trip. If you don’t pull together your research and write your family history, who will? Writing your family history can be fun and rewarding, a creative way to bring your ancestors to life for you and your readers. Just as researching your roots is a personal quest — since no two people except biological siblings have the exact same ancestry — so is writing your family history. Choose one of the seven genres of genealogical writing that suits you, your ancestry, your writing style and your personality. Then start writing. And, while you’re at it, enjoy a second helping of lasagne.

From the February 2001 issue of Family Tree Magazine