Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

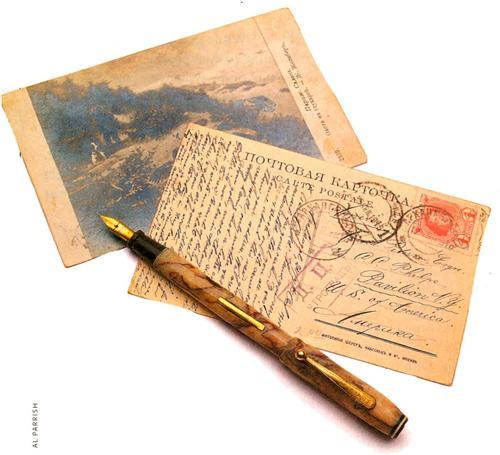

My husband works with computers, not old documents, so one night when he glanced over as I sat transcribing a census page, he cried, “How can you read that?” Used to the uniformity and predictability of fonts on a computer screen, he was baffled by the curlicues and chicken scratches on the old census document. He couldn’t read it at all.

You may have felt the same way when you’ve struggled to decipher handwritten pages about your ancestors, from census pages to deeds to personal family letters and diaries. The answers you’re after may be there, but they might as well be written in Martian.

The good news is, as I reassured my husband, the more you read older documents the more familiar you’ll become with old-fashioned handwriting. But it does take patience to learn to read and transcribe unfamiliar script and to understand the clues in a manuscript.

ADVERTISEMENT

Eventually, you can even “read between the lines.” While graphologists claim that handwriting analysis provides insight into the personality of the writer, there are also genealogical hints in a person’s handwriting. For instance, penmanship can establish a time period for a document and the educational level of the person who wrote it.

Here are seven steps to help you get started discovering new things about your family through their handwriting.

1. Match Handwriting to History.

Today we equate literacy with being able to read and write, but that’s strictly a 20th-century concept. In earlier centuries, writing was taught separately from reading. In fact, questions regarding an individual’s skill in reading and writing continued as separate columns on the US census until 1930.

ADVERTISEMENT

Reading, after all, was important to study the Bible, but writing wasn’t deemed essential. Even signing your name wasn’t required: Officials wrote documents and men who couldn’t write signed their mark, a design that distinguished them from others.

As writing came to reflect economic affluence or social position, however, businessmen, clergy and public officials began to learn. In Colonial America, individuals could enroll in private writing classes as early as 1684, or use self-teaching manuals. In the 18th and 19th centuries, penmanship masters traveled around the country teaching the fine art of handwriting to persons wanting to sign their name or to young women using penmanship as a means of artistic expression.

Handwriting is not only different for each generation of your family tree, but also reflects the writing technology available at the time. The shape and style of the pen nib influenced the development of new handwriting methods. For example, it’s difficult to create certain scripts with a flat pen nib. You can study 20th-century handwriting methods by asking relatives to write the alphabet on a separate sheet of paper and comparing them. While individuals tend to develop their own style regardless of the method taught in school, certain letter formations will let you identify when they were taught to write and in what script.

2. Recognize the Style.

As you become familiar with different types of handwriting, you can set an undated document into a time frame and learn more about the person who wrote the words. In Colonial America, most of the population learned one style of handwriting, but well-educated individuals often learned several different methods of script or “hands.” For instance, John Winthrop of Massachusetts often wrote in various scripts within the same sentence. At least four different calligraphic styles of script — Gothic, Italian, Secretary and Roundhand — co-existed in Colonial America.

Men and women often learned different scripts, so someone would be able to identify the sex of the writer from their handwriting. The same was true for social status: Private secretaries wrote in a particular style, while their employers would sign in another, thus establishing that they did not write the document. According to Tamara Plakins Thornton, author of Handwriting in America (Yale University Press), different hands “were a marker of a specific occupation, gender or class.” Not until the late 19th century did one method become dominant in the United States.

Here’s a quick look at some styles you’ll encounter, and when they were popular:

- Secretary, Court Hand or Gothic, 1600s: Known by multiple names, this is the most common script you’ll encounter in 17th-century materials. It reflects the handwriting style of early English immigrants. You’ll also see Mayflower Century script, which is a combination of this style with Italian and, by 1700, the Roundhand script, below.

- Italian, 1400s-1700s: The script we call italics is also the Italian hand. Instead of the block letters of the Gothic script, Italian has rounded letter formations. Queen Elizabeth of England used cursive Italian script in her writings.

- Roundhand or Copperplate, 1700–late 1800s: As copybooks — self-teaching handwriting manuals — began to be printed by copperplate engraving, the Roundhand became popular. It also helped introduce new writing implements so that the fine script could be duplicated. Roundhand is recognizable by its thin upstrokes and thicker downstrokes.

- Spencerian, 1865-1890: This uniquely American handwriting system was derived from three competing penmanship masters. Characterized by flourishes, Spencerian reflected the feminine pursuits of the Victorian period. Writing was a slow process because of the number of loops and times the pen lifted from the page to form letters. Spencerian handwriting became the dominant method of script in the late 19th century, taught in schools and in copybooks.

- Palmer, 1880-1960s: Austin Palmer developed his method of plain, legible script to be more suited to the fast pace of business than the slow pen strokes of the Spencerian method. Ask your parents or grandparents about the movement drills practiced in the classroom to master Palmer penmanship.

- D’Nealian, 1965-present: If you have children or grandchildren currently learning to write, this is probably what they’re being taught. The letters in the printed version of D’Nealian help children learn manuscript writing without learning different letter formations. See the Wikipedia D’Nealian entry for examples of this style.

Reading between the lines

Handwriting can reveal more than just what your ancestor was writing about — it also may reveal personality traits of the writer herself.

Since the 1600s, various theorists have tossed around the idea that handwriting reveals personality. But it wasn’t until the 20th century that graphology — the inference of character from a person’s handwriting — emerged as a “science.” An individual’s character shows itself in the size of letters, along with how they are slanted, decorated, angled and curved (a t crossed near the top indicates vanity, for example). Today, psychologists, teachers, social workers and personnel departments hire graphoanalysts to study the handwriting of living persons. Certified graphoanalyst Christina Meide decided to apply her training to a longtime hobby: genealogy.

“Handwriting can show many amazing traits — good traits — in an individual who has taken the wrong road in life,” Meide explains. “It is not unusual for me to hear, ‘this can’t be right. My great-great-uncle was a horse thief and an unfaithful husband. This may be true, but Great-great-uncle was also a person with a very complicated personality. After all, he wasn’t born ‘bad.’”

To learn more about Meide and her work, see her website. Also visit the International Graphoanalysis Society; they train handwriting specialists.

3. Adjust for Stylistic Variations.

If you’ve ever tried to read a document from the 17th century or earlier, you know it can be like learning another language. Part of the reason it’s so challenging isn’t just the different script — you’ll also encounter variations such as these:

- Handwriting difficulties: Illegible handwriting can be evidence of improper or interrupted instruction, illness or even learning disabilities. In earlier centuries, pupils learned writing through the use of copybooks, requiring students to exactly duplicate the letters and style shown. If your ancestors’ schooling wasn’t completed, penmanship lacked the discipline of the repetitious practicing. Evidence of certain types of medical conditions and old age appear as tremulous writing with shaky letter formation. Illegible handwriting also may have been caused by dysgraphia, a learning disability.

- Immigration clues: The handwriting styles discussed here are American versions. Penmanship styles differ in other countries and cultures. If you’re trying to read script from someone who didn’t learn the technique in this country, there will be variations in letter formation and often in the way certain numbers appear. Handwriting can help verify that your ancestor immigrated to the US after learning to write in his or her country of origin.

- Shorthand and abbreviations: A type of shorthand still frustrates researchers trying to read the letters of Roger Williams, one of the original founders of Rhode Island. Even after being sent to a code breaker, many of his notes remain indecipherable. If you find self-created shorthand in family papers, the writer probably utilized it to expedite the writing process and possibly to confuse anyone trying to sneak a peek at a diary or letter. Abbreviations are a type of shorthand, too. Some standard ones appear in official documents, while others are individual adaptations. When trying to decipher shorthand or abbreviations, it helps to create a reference chart of the idiosyncrasies in each manuscript.

- Left-handedness: While not all left-handed individuals write with a backward slant, penmanship with that feature can indicate your ancestor’s dominant hand. But be aware that at least one writing master in the mid-19th century purposefully taught his pupils to write with a backward slant.

- Flourishes: Some writing instructors taught pupils to create artistic works with penmanship. With the same pen strokes used for letter formation, students could draw birds and borders with pen flourishes for graphic interest.

- Fraktur: Decorated writings of the Pennsylvania German folk art tradition, Fraktur began appearing in Germany, Alsace and Switzerland in the early 17th century. Fraktur most commonly appears on certificates for births and baptisms and in family records for immigrants from those areas.

4. Check Your Spelling.

Having only one way to spell a word is a 20th century concept springing from widely available free public schooling and mandatory education laws. If you can’t figure out a word once you’ve transcribed it, try saying it aloud; it might be phonetic.

Older documents also often contain archaic words and phrases that are unfamiliar today, or words whose meaning has changed. Consulting the Oxford English Dictionary or a dictionary from the time period of the document will usually explain the meaning. There are also genealogical dictionaries of compilations of unusual words and phrases commonly found in materials used by family historians. You’ll find hundreds of free online dictionaries to help you with foreign, archaic and specialty terms.

5. Go Letter by Letter.

Different styles of handwriting have idiosyncrasies that can lead to transcription errors. For instance, 17th-century documents written in Secretary hand are full of abbreviations and letter formations that look strange to us today. In Roundhand, the letter s is formed by a long flourish that’s easily confused with a p or an f.

In her best-selling book Unpuzzling Your Past (Betterway Books), Emily Croom offers these tips for making sense of old script:

- Lower-case letters u, n, w and m often look alike.

- Watch for undotted i’s and uncrossed t’s.

- Words with double ss can appear to be fs or ps.

- Capital letters S, L and T can have a similar appearance.

- I and J can look the same.

Tackle these challenges one step at a time. Spend time poring over a document, looking at each word and identifying all the capital and lowercase letters that you’re sure of. When, you find a letter that’s indecipherable, try comparing it to letters in other words in the manuscript until you find similarities. There will be times when this doesn’t work, but in many cases you can locate an approximate match. Deciphering each document letter by letter creates a stylistic alphabet chart and builds your self-confidence.

6. Put it in Context.

Whenever I approach a new document, I think of my daughter who’s learning to read. She doesn’t try to read a new book all at once; she takes it one word at a time. When she encounters a word she doesn’t recognize, she tries to understand it in the context of the sentence. The same methods work for old documents. There are almost always words that will scare you with their illegibility. When this happens, step back from the word and read the rest of the document to see if you can pick up any contextual clues.

Remember how code breakers work, looking for patterns that let them turn gobbledygook into plain English. If you keep seeing a mystery letter followed by he, it’s probably a t, making the.

7. Overcome Other Obstacles.

It may not be a problem with the handwriting that stops you from completely understanding a document. Physical deterioration — faded ink, water damage or worn documents — can obscure single letters or even whole paragraphs. My ancestors almost always end up on a census page smeared from exposure to water.

Still stumped? Sometimes a fresh set of eyes can help — enlist the aid of another researcher or a professional with manuscript experience. What you found difficult, someone else may be able to read effortlessly.

And be patient. Sometimes trying to read an old document takes hours or even days. While you want to be able to read it as easily as the words in this article, it may not be possible. You wouldn’t expect to learn Greek in an afternoon, so why set yourself up for failure by rushing the process? When you become frustrated, set the document aside for a day or two until you’re ready to try again.

Ultimately, the rewards are worth the effort. Reading an old family letter or diary is a bit like time travel. You have a sense of what your ancestors experienced, in their own words. Even deciphering an old census page or courthouse document in a stranger’s handwriting can be a thrill — you’re reading the words of someone who actually met your ancestor, after all.

Nothing in the sterile fonts on a computer screen can quite compare. So when my husband asks, “How can you read that?” I have to answer, “How can you not want to read it?”

A version of this article originally appeared in the October 2001 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: January 2025

FamilyTreeMagazine.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for site to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to affiliated websites.

ADVERTISEMENT