The Mid-Atlantic states are as central to America’s legacy as, well, Uncle Sam. That American icon originated in the habit of a Troy, NY, meatpacker named Samuel Wilson, who stamped each of his boxes with “US Beef” — misinterpreted by consumers who thought US was short for Uncle Sam. From New York City’s Statue of Liberty to Philadelphia’s Liberty Bell and Independence Hall to Baltimore’s Fort McHenry, whose War of 1812 siege inspired “The Star Spangled Banner,” this region has been a canvas for scenes of American history. Delaware, “The First State,” led the way in ratifying the Constitution. Key battles of the Revolution were settled in New Jersey. Millions of immigrants first set foot in America at Ellis Island, off the shore of New York and New Jersey. Women’s suffrage got its spark at Seneca Falls, NY.

The Mid-Atlantic states gave us many of the best-known names in our history, too, from Benjamin Franklin and Alexander Hamilton to Babe Ruth and Wilt Chamberlain. New York alone supplied five US presidents — Martin Van Buren, Millard Fillmore, Chester Alan Arthur, Grover Cleveland, Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt. The region gave birth to classic American authors such as Washington Irving, Herman Melville and Walt Whitman. It was home to many of the 19th century’s wealthiest citizens — Vanderbilt, Rockefeller, Dupont, Carnegie, Mellon.

If your ancestors have roots in Maryland, Delaware, Pennsylvania, New York or New Jersey, you’ll discover a wealth of genealogical resources for tracing them. Genealogist and area expert Gary Boyd Roberts offers these tips for getting started:

• The best published county sources are county and biographical encyclopedic histories known as “mug books” for their combination of data and photographs supplied by the individuals who paid to have their “mugs” put in. You can find mug books in most local history collections. Who knows? You might discover a photo of your ancestor.

• Take advantage of the numerous in-depth reference books on the various states, many of them published by Genealogical Publishing Co. (see page 58).

• For published genealogies of area families, consult family histories printed in journals such as The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, The National Genealogical Society Quarterly and The American Genealogist. Use the Periodical Source Index (PERSl), available at larger libraries, on CD-ROM or as part of the Ancestry.com database subscription <Ancestry.com >, to find relevant articles.

You’ll also find helpful resources to start your search from the Family History Library (FHL). You can use its research helps for each state at <www.familysearch.org> (click the Search tab, then Research Helps) as genealogical guidebooks to truly understand the region and focus your efforts.

New beginnings

Unlike New England, which was primarily settled by the English, the Mid-Atlantic region boasts early Dutch, Swedish, German, French and English arrivals, as well as a variety of religious refugees. The Dutch settled New York as New Netherland; Jews also began settling in New Amsterdam (New York City) in the 1650s. In 1664, the British took over New Netherland and renamed it, though the area’s Dutch heritage persisted enough to flavor the works of Washington Irving.

New Jersey was spun off after the British takeover of New Netherland, when the Duke of York rewarded two faithful supporters with their own colony. The new colony’s owners promptly began advertising for settlers, including luring away New Englanders. Newark, for example, was founded in 1666 by Puritan families from New Haven, Conn.

Maryland’s English immigrants typically arrived as indentured servants and convicts; the colony, chartered in 1632 by Lord Baltimore, also offered refuge to many Roman Catholics.

Delaware was briefly the heart of New Sweden, the only Swedish colony in America, founded in 1638. The Dutch soon took control, but a semi-independent “Swedish Nation” of Swedes and Finns remained until 1681, when William Penn received his charter for Pennsylvania and three counties that became Delaware. The future state’s boundaries weren’t finally settled until 1750.

Pennsylvania, with its Quaker heritage of excellent record-keeping, delights researchers with its meeting records: These detailed accounts kept by the Society of Friends come complete with vital statistics. William Penn began Pennsylvania as a colony based on religious freedom — his Quaker faith taught toleration — so a variety of faiths and cultures settled here. Use William Wade Hinshaw’s Encyclopedia of Quaker Genealogy (Genealogy.com CD 192, $59.95; also available as part of a Genealogy Library online subscription, $49.99 a year) to trace Quaker family history and their migrations.

For finding other early settlers, try resources such as P. William Filby’s Passenger and Immigration Lists Index (Genealogy.com CD 354; also available as part of the International and Passenger Records Collection online subscription, $79.99 a year) and Peter Wilson Coldham’s four-volume The Complete Book of Emigrants, 1607-1776 (Genealogical Publishing Co.) and The Complete Book of Emigrants in Bondage, 1614-1776 (Clearfield Co.). You can access Coldham’s books electronically on Genealogy.com CD 350 and through its International and Passenger Records subscription. And you can always use these references in their original book form — for free — at genealogy libraries.

Immigration central

When most researchers think of immigration, the first thing that comes to mind is Ellis Island in New York City’s harbor, but the Mid-Atlantic region actually had several other ports of arrival, including Baltimore and Philadelphia. If your ancestors arrived after Ellis Island opened in 1892, check the vast database at <www.ellisisland.org> to find their passenger lists. (See page 24 for more advice on researching Ellis Island arrivals.)

Otherwise, the National Archives and Records Administration has several different microfilm sets for arrivals at Atlantic ports. Consult the Immigrant and Passenger Arrivals information on its Web site <www.archives.gov> or visit one of its 13 regional facilities to search Soundex indexes (which group similarly spelled names) to:

• Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at Baltimore, Maryland, 1820 to 1897 (M327)

• Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at Baltimore, Maryland, 1891 to 1909 (T844)

• Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820 to 1897 (M237)

• Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at Philadelphia, 1800 to 1882 (M425)

• Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at Philadelphia, 1883 to 1945 (T840)

So many immigrants came to the area in the late 19th century that the population of New York City tripled from 1860 to 1900.

Westward migrations

Researchers looking for ancestors in upstate and western New York and Pennsylvania will wish they could be Rip Van Winkle in reverse — instead of going forward 20 years, they’ll want to travel backward to unravel the mystery of the missing records that plague most researchers. When a branch of the family tree from New England is noted in print as having “gone west,” it refers to territories west of their starting point — not the West of cowboys and Indians. In the 18th century, this could mean New York or Pennsylvania. Henry Hoff, editor of the New England Historical and Genealogical Register and former editor of The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, reminds researchers looking for elusive ancestors to check for interaction and emigration from neighboring states. For instance, settlers of upstate New York came from New England; early Philadelphians moved west following old Indian trails; emigrants from Pennsylvania and Maryland settled Delaware.

Westward migration was further encouraged through Revolutionary War land grants that offered parcels in New York and Pennsylvania. You can check to see if your ancestor received one of these grants by consulting Virgil D. White’s four-volume Genealogical Abstracts of Revolutionary War Pension Files (National Historical Publishing Co., out of print), which is available in libraries, or Lloyd DeWitt Bockstrock’s Revolutionary War Bounty Land Grants Awarded by State Governments (Genealogical Publishing Co.).

The western regions of the Mid-Atlantic states also expanded through the new transportation and trade routes offered by man-made canals. The Erie Canal took eight years to build, but when completed, its water route from the Hudson River to Lake Erie helped make New York City a major port. The canal also provided transportation to people seeking to settle in the west. Find out more about this fascinating waterway at <www.history.rochester.edu/canal> or consult the online Guide to Canal Records in the New York State Archives at <www.archives.nysed.gov/holding/aids/canal/content.htm>.

Metropolitan maneuvers

Another inescapable aspect of Mid-Atlantic ancestor hunting is that the region encompasses some of North America’s largest cities. At some point, your research strategy here will likely become an urban genealogical hunt. So it makes sense to learn some techniques for finding ancestors in densely populated areas:

•Learn the city’s history. Each city has a different growth pattern and population. By studying the history, you’ll save yourself time and money looking for records.

•Use directories. Take advantage of city and telephone directories whenever they’re available to help you sort through people with the same name and identify street addresses for census research.

• Locate a local resource. Most metropolitan areas feature a historical society or have a local history collection at the public library. Take advantage of these resources to efficiently find what you’re looking for. Library and archives staff can be one of the best sources of genealogical reference help in these repositories.

• Find maps. Urban maps such as the Sanborn Insurance Atlases (often available at large public libraries) contain a phenomenal amount of information, including even the composition of the building your ancestor owned or rented. Maps also help orient you to various parts of a city.

• Read the paper. Metropolitan areas usually have at least one English-language newspaper, as well as one published by each new ethnic group as it assimilated in the area. Look for newspaper indexes and special collections of newspapers to help understand your ethnic roots or maybe even find a published vital record or business notice about your ancestor.

• Hire a professional researcher. If you’re trying to do research long-distance and the wait for records is interminable, consider enlisting the services of a professional researcher in that area. While staffing is an issue at many archives, a walk-in patron can usually expedite the process. The Association of Professional Genealogists has a list of members on its Web site <www.apgen.org> to help you find a researcher with relevant expertise.

Brick-wall busters

Don’t be discouraged by a lack of vital records, ink-smeared census documents and that all-too-common “all the records burned in a fire.” Sometimes, you can overcome those missing ancestors or black holes in your research with patience and perseverance. Professional genealogist Edward Steele offers this advice: Success, he says, “requires an understanding of how records were initiated, by what legal or civic bodies they were created, and where they are now kept. Also, counties were changing their boundaries at the time that many families were passing through, so researchers may be searching in the wrong jurisdiction. And finally, many families did simply ‘pass through,’ staying for perhaps a generation or two (or not even that long) during the period before civil registration of vital events.”

So get out there and problem solve by consulting genealogy guides, hiring researchers or doing whatever will help you break down the problem into small pieces. Don’t forget to create a timeline of your ancestors’ lives. Consider what types of records they created in their lifetime and think creatively. Use church, business and court records, and read any case study in print or online that resembles your research problem. You never know where the solution will appear, but looking in as many places as possible improves your odds.

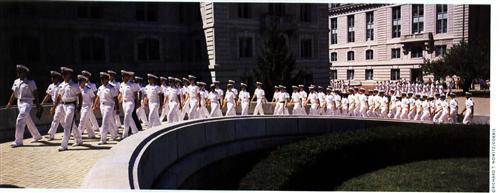

The US Naval Academy in Annapolis, Md., is a National Historic Landmark.