Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

“Old Trace,” the sign reads, pointing away from the ribbon of highway into the deep Tennessee woods. I follow, feeling as if I’m going to a/sacred site, where many spirits still linger. I have to drop down into this eroded remnant of the old frontier trail, the Natchez Trace, because it has sunk at least four feet below the surrounding forest. Over the centuries, thousands passed here, carving their footprints and their stories into the land.

The serpentine trail once snaked all the way from Nashville, Term., to Natchez, Miss., for a total of nearly 500 miles. The Natchez Trace was first beaten in place by the hooves of buffalo, who were drawn to the natural salt flats in the South, then by hunting parties of moccasin-clad Choctaw and Chickasaw Indians. They were followed by French explorers, pioneers and frontiersmen, boatmen, post riders and soldiers. John James Audubon was no stranger to the Trace, and Andrew Jackson was a frequent traveler. Meriwether Lewis passed this way. The Natchez Trace became an official “post road” to expedite mail delivery, and the silhouette of the post rider has been adopted as the official symbol of the modern-day Natchez Trace Parkway.

The old Natchez Trace fell into disuse in the 1800s after the steamboat was invented and the boat crew, called Kaintucks, found a quicker way home. Nobody thought much about the Trace again until 1938, when the Daughters of the American Revolution <www.dar.org> convinced the powers-that-be to preserve this chapter in our nation’s heritage and work toward creating a national historic parkway.

Today, you can retrace this historic overland route by following the Natchez Trace Parkway <www.nps.gov/natr>, a two-lane modern highway constructed by the National Park Service, which closely follows the course of the original Trace. The purpose of the parkway is to provide and maintain a scenic and recreational roadway commemorating the historic Natchez Trace, with an emphasis on the 1790 to 1820 period. For those weary of the congestion and speed of interstate highways, this long national parkway is a sanctuary.

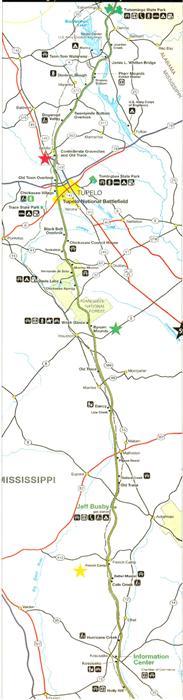

The parkway is a billboard-free route with a speed limit of 50 miles an hour. It’s generously punctuated with interpretive signs and turnouts that lead to picnic areas, campgrounds, nature trails, historic points of interest and remnants of the old Trace. Convenient mileage markers alert you of your progress, and a helpful guide and map put out by the park service ensure that you don’t miss a thing. All along the route, you can hear stories of people on the move, of the age-old need to get from one place to another.

I have come with my family from Pennsylvania to follow the course, to immerse ourselves in this place, hoping to learn about the people who came before us and absorb some of their adventurous spirit. The slower you travel on the Natchez Trace Parkway, the better, for there’s so much to see, learn and experience. To take it even more slowly than automobile travel allows, my husband, Todd, and I have chosen to ride two tandem bicycles with our 10- and 12-year-old children, stretching our trip out to 10 days. But whether you have a weekend or a two-week vacation to spend on the Trace, it’s one of the most fascinating and richly historic routes you can explore anywhere in America.

Travel Tips

For guidance along the trail, stop by the Natchez Trace Park Headquarters and Visitor Center (2680 Natchez Trace Parkway, Tupelo, MS 38804, 800-305-7417, <www.nps.gov/natr>), located in Tupelo, Miss., at milepost 266 of the Natchez Trace Parkway. This site offers exhibits, information, books, a short interpretive film and restrooms. Friendly, knowledgeable rangers and personnel can answer almost any question you have about the Trace. The free Official Map & Guide contains history, a milepost listing, campground locations, a list of facilities and other essential information. The headquarters is open daily from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m.

The Natchez Trace is a National Scenic Trail, with sections built away from the paved roadway, utilizing the original Trace. See <www.nps.gov/natt> for information on the Natchez Trace National Scenic Trail.

There are no fees or tolls for National Park Service facilities along the parkway. Just remember that it’s also a designated bike route, so watch for cyclists.

You won’t find any motels along the parkway itself; you’ll need to detour to nearby towns and cities. Chambers of commerce provide information about their communities’ lodging, restaurants and other services and facilities. The Natchez National Historic Site Visitor and Reception Center is the official welcome center for the city of Natchez. For more on Natchez, contact the Natchez Convention & Visitor’s Bureau (640 S. Canal Street, Natchez, MS 39121, 800-647-6724, <ncvb.natchez.ms.us>).

An excellent guidebook, Traveling the Natchez Trace by Lori Finley (John F. Blair), also can add to your enjoyment of the Trace.

Down into Dixie

Today’s Natchez Trace Parkway begins southwest of Nashville on Tennessee 96, and ends 450 miles later, a few miles north of Natchez on US 61. The northern section crosses the western part of hilly Tennessee, struggling to maintain elevation through a mostly deciduous forest. It dips down off these thousand-foot hills through an occasional tobacco field. Deer and wild turkey are plentiful and can be seen grazing on the grassy banks of the parkway. In the spring, flowering white dogwoods look like curtains of lace thrown over the green forest.

The southern portion of the parkway is much lower and flatter, with the lowest point at milepost (MP) 105 in Mississippi. The prevailing species of trees include the southern red oak, white oak and hickory. Beautiful stands of tupelo and bald cypress poke out of the mysterious swampland. You’ll pass cotton fields and soybeans and see armadillos and alligators.

You’ll have to pick and choose which “attractions” along the way to put your time into, depending on your interests. The colorful towns along the route promise to make your experience on the Trace memorable. You’ll enjoy great Southern meals, too: fried catfish, bright-red crawfish, flaky biscuits and savory gumbos. Side trips take you into the elaborate military park in Vicksburg, to ancient Indian burial grounds, and to Hernitage, Andrew Jackson’s home. Or start off with foot-tapping country music in “Music City, USA” — Nashville, largest city on the Trace.

Roughnecks and waystations

The word trace comes from the French word tracir, to follow a course or trail, to make one’s way. Of all the people who followed the Natchez Trace, I find the Kaintucks the most fascinating. These were men who hailed mostly from old Kentucky (hence their nickname), but also parts of Pennsylvania, Ohio, Missouri and Virginia. Looking for new markets for their surplus goods, the Kaintucks built flatboats and barges and loaded them with tobacco, iron, rope, potatoes, whiskey, cattle and pine boards. They floated down the Mississippi River to the ports of Natchez and New Orleans. The trip took three weeks to cover the river distance of 2,000 miles.

Once in port, the Kaintucks broke up their boats and sold them for lumber, sewed their cash into shirts and coat linings to discourage theft, and began the long overland trip back north up the Natchez Trace, the most direct way home. Travel peaked on the Trace in 1810; an estimated 10,000 Kaintucks rode or hiked this route.

It took another three weeks to walk the 500 miles on the Trace, but there were many more dangers and hardships. An exhibit depicting travel in those early days reads: “This early interstate road-building venture produced a snake-infested, mosquito-beset, robber-haunted, Indian-pestered forest path. Lamented by the pious, cussed by the impious, it tried everyone’s strength and patience.”

Understandably, these conditions produced a rough and rowdy lot of travelers. Alexander Wilson, a friend of Meriwether Lewis, described the Kaintucks as “dirty as Hottentots, their dress a shirt and trousers of canvas, black, greasy, and sometimes in tatters, the skin burnt wherever exposed to the sun, each with a budget [small bag or pouch], wrapt up in an old blanket, their beards eighteen days old, added to the singularity of their appearance, which was altogether savage.”

We think about these “savage” Kaintucks as our family follows the Trace, imagining what life was like 200 years ago. We stop at Gordon House and Ferry Site (MP 407.7), where John Gordon once operated a ferry across the Duck River. We rest by the cool Jackson Falls, as did many a weary traveler before us. Both are side trails off the parkway. We pay a sobering visit to the ruins of the Grinder House (MP 385.5), where Meriwether Lewis met his death on Oct. 11, 1809 — some say it was murder; others, suicide. A monument depicting a broken concrete column dramatizes the explorer’s death.

The Grinder House was one of more than 50 “stands” along the Trace, farmers’ homes that offered primitive lodging for travelers. Weatherbeaten travelers would appear on farmers’ doorsteps, asking for refuge; the farmers opened their doors to the travelers, at first out of kindness, but soon as an important source of supplemental income. The farmers added extra rooms and provided care for horses, as well. Travelers could reach each stand by about a day’s walk — 25 miles — from the previous location. Sleeping quarters were tight; farmers crammed as many as 50 men on the floor. Only one intact stand remains, at Mount Locust (MP 15.5), where the park service provides a marvelous interpretive program. In the fully furnished house, volunteers dressed in period clothing explain life during this time period.

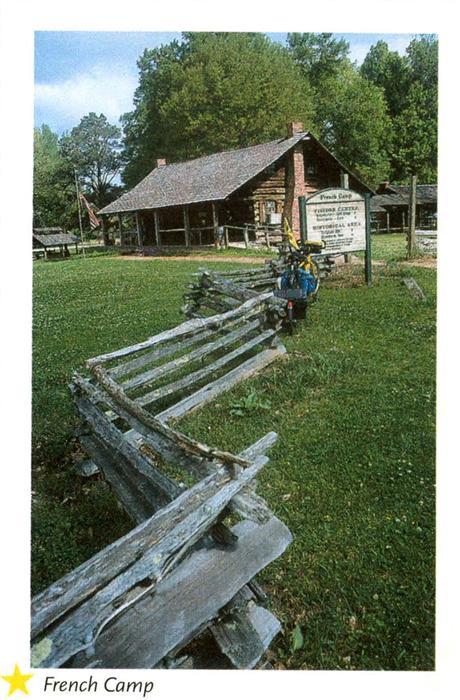

Another fascinating stop is historic French Camp, Miss. (MP 180.7), where Louis LeFleur and his Choctaw wife established a stand in 1812. LeFleur started a famous school for Native Americans, French Camp Academy, which still operates today. The school is well-known as the state leader in astronomy studies because the area has little or no light pollution. Its observatory has several of the state’s largest telescopes. At the annual French Camp fall festival, visitors can watch old-fashioned sorghum being made from cane sugar in a process relying on a mule-powered grinder.

Indians and soldiers

These were Indian lands that the Kaintucks crossed, but the Native Americans granted the travelers permission and even offered help. At the Chickasaw Village (MP 261.8), an exhibit describes Chickasaw daily life and early history. You can walk among the foundations of their homes, saunter down nature trails where interpretive signs show which plants and herbs the Chickasaw used, and gaze at the same ancient trees that marked the tribal boundaries.

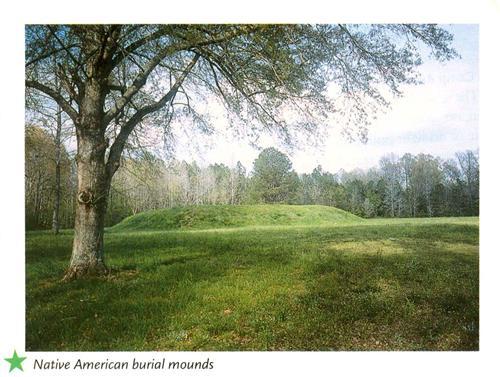

Along the Trace, you can see a half-dozen burial mounds left by even earlier Native Americans. The second-largest one in America, Emerald Mound (MP 10.5), covers eight acres and is more than 700 years old. My children and I walk around the grassy mound, wide-eyed, reading strange stories of how the wife and children of the dead chief were sometimes killed, as a way of expressing grief. You get an eerie feeling near the mounds. We imagine the ancient people moving dirt by the basketfuls — for as much as 100 years — to create the mound.

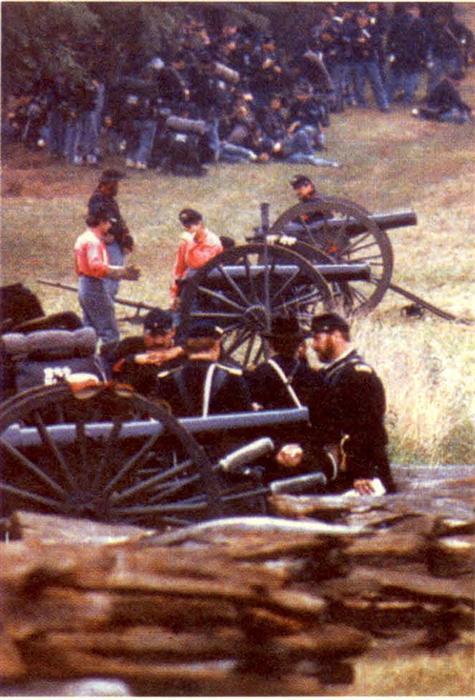

Even after the Trace was no longer a frontier byway, it continued to see history being made. The blood of thousands of Union and Confederate soldiers was spilled on and around this well-traveled path. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant marched troops along the Trace in 1863 to take nearby Vicksburg. Grant restrained his troops’ assault on the town of Port Gibson, Miss. (MP 39.2), now a short jaunt off the parkway, saying it was too beautiful to burn. Port Gibson boasts Mississippi’s first National Historic District. You can enjoy a fascinating self-guided tour of the town and its dozens of historic homes and buildings. Then, spend the night at a stately old southern mansion, Oak Square Plantation (1207 Church St., 601-437-4350 or 800-729-0240), built circa 1850, which is on the National Historic Register and now serves as an inn.

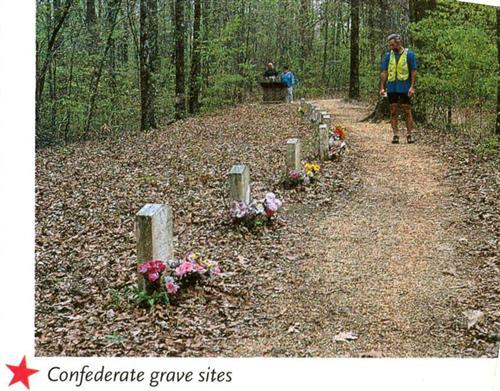

Between MP 270 and 269, near Saltillo, Tenn., 13 unknown Confederate soldiers are buried near the old Trace. Elaborate bouquets of brilliant plastic flowers adorn each grave.

Also along the parkway is the Tupelo National Battlefield <www.nps.gov/tupe>. This marks the site where, on July 13 and 14, 1864, Lt. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest tried to cut the railroad supplying the Union march on Atlanta.

Natural diversions and antebellum pleasures

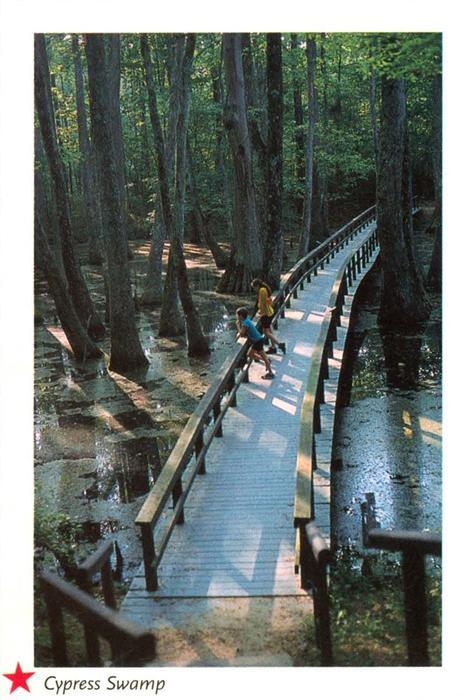

Back on the parkway, however, life abounds. Blankets of red clover cover the wide shoulders. Airy Spanish moss waves in the branches of the oaks. Melodious bird songs fill the air; birdwatchers can look for up to 215 different species. Fifty-seven types of mammals also compete for your attention. Out of all the natural wonders along the Trace, our favorite is the Cypress Swamp (MP 122), where you can enjoy a 20-minute self-guided nature trail through a water tupelo/bald cypress swamp. We excitedly spot alligators sulking in the murky water.

We stare, mesmerized, at the 400-year-old, 150-foot cypress trees, with their gigantic belled trunks surrounded by water.

To reward ourselves for cycling all the way from Nashville, we spend the night in an elegant antebellum mansion. At last in Natchez, we tour the 1818 Greek Revival Monmouth Plantation( 36 Melrose Ave., 601-442-5852 or 800-828-4531, <www.monmouthplantation.com>), a National Historic Landmark and now a small luxury hotel. It’s the former home of John Anthony Quinten, one of the South’s most important public figures, who made his fortune in cotton and sugar.

At Monmouth Plantation, we learn all about life in the Old South, when cotton was king. We learn that ladies held fan-shaped objects called “facesavers” when they sat by the fire to keep warm — to keep from melting the beeswax they slathered on their faces to cover up smallpox scars. No wonder in old portraits their faces look like porcelain! We walk the 26-acre gardens, with their romantic fountain, pond, bridges and terraces, sharing the paths with ladies dressed in great, hooped period ball gowns. Then, using the same silver and heirloom china that plantation owners used years ago, we enjoy a fabulous dinner. The present owners, Loni and Ron Riches, who restored the mansion, believe in letting guests use and enjoy the antiques and heirlooms.

After dinner, we take a walk down to Natchez Under-the-Hill, the historic district where our story comes to an end. This strip of restored wood-frame buildings once consisted of taverns, “bawdy houses” and other establishments designed to entrap boatmen and take their money before they headed back up north along the Trace.

The Natchez Trace Parkway has a way of making you into a history-lover, even if you didn’t start out that way. Everywhere are ghosts, stories and remnants of life that came before. The slower you go, the more stories you’ll hear, and the more you’ll feel you’re following in the tracks of all those who traveled this way before you.