You’re flying down the information superhighway, picking up ancestors left and right in dozens of online databases. You’re confident you’ll soon have your family tree traced back to Colonial days.

You’re flying down the information superhighway, picking up ancestors left and right in dozens of online databases. You’re confident you’ll soon have your family tree traced back to Colonial days.

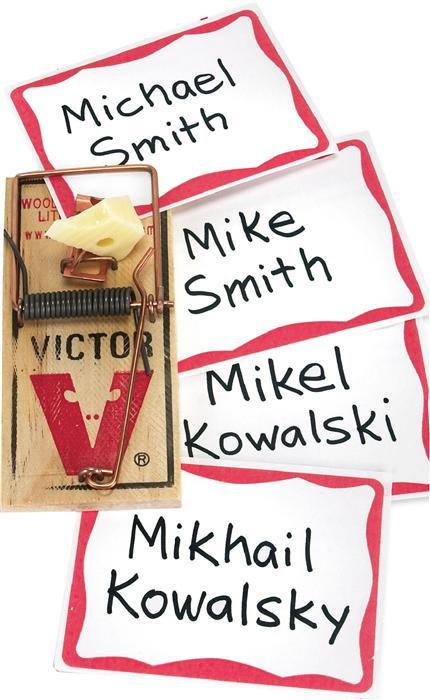

But wait: Are you sure those are your ancestors? Have you stopped to think about whether the dates and places you’ve uncovered actually make sense? It’s not hard to get caught up in the ease of online ancestor searching especially when you’re hungry for a big bite of family facts. But if you don’t pause to question your assumptions, you could be barking up the wrong family tree. Claiming someone else’s John Smith as your own, for example, and then researching his parents, may mean hours of backtracking once you realize your mistake.

By all means, keep cruising the thousands of genealogy Web sites out there. But do so with your eyes wide open — and with our strategies for avoiding 10 traps that can lead your ancestor hunt astray.

TRAP #1: I found my family tree on a popular site — I can trust the information.

Good news! Someone has traced your great-grandfather’s line back seven generations, and that information is yours for the taking via one of the many well-known pedigree databases, such as GenCircles GlobalTree <www.gencircles.com/globaltree> and Ancestry World Tree <www.ancestry.com/awt>. Or so you think.

You have every reason to be excited, but you still need to take a close look at those names, dates and places. Even the most meticulous genealogist can make a mistake, leading you to believe, for instance, that Great-great-grandma was born in 1855 rather than 1865, or that she died in Springfield, Miss., not Springfield, Mass. Always double-check the information you find online. Has the genealogist who submitted those names cited her sources? If not, ask where she got the information. You’ll want to verify that data in original records, just in case even a small typographical error sneaked in.

Of course, a typo’s the least of your worries. What if this genealogist erroneously intermingled your family tree with someone else’s? How do you know she researched the right Robert Jones? Keep in mind that researchers of all experience levels publish family data on the Web. The sites that host that user-submitted information — even the online genealogy meccas Ancestry.com <Ancestry.com > and Family-Search <www.familysearch.org> — don’t double-check it for you.

TRAP #2: That’s my ancestor’s name, so it must be him.

Do you know how many John Smiths have walked this earth? Enough to make genealogists nuts. If you have a John Smith in your family — or an ancestor with an equally common moniker — you probably know better than to assume every John Smith you find online is yours.

But say you have an ancestor with a decidedly uncommon name, such as Chris Kringle. Yes, it’s unlikely that more than one Chris Kringle lived in your ancestor’s town at any given time. But, hey, you never know. Before you accept a Chris Kringle as your own, be sure his vital information makes sense. Was he born 50 years after your Chris Kringle should have been? Then he’s probably not your man. If the dates and places do match up, look at Chris’ parents, siblings and children. No two people with the same name will have the same relatives.

If you’re still not sure you’ve got the right Chris, professional genealogist Sharon DeBartolo Carmack suggests turning to land records: “If there are two or more men in a community with the same name, land records often include descriptive identifiers such as ‘John Williams the blacksmith’ and ‘John Williams the wheelwright.’ Or you may find the clerk used ‘junior’ and ‘senior,’ or ‘the younger’ and ‘the elder.’ Don’t assume, however, that these identifiers indicate a father-son relationship. They simply indicate that one man was older than the other; the men might not be related at all.”

Carmack also warns that names such as Sarah and Mary were common, so a man might have married two women with the same first name. “The unwary family historian may assume her great-great-uncle Samuel had just one wife named Mary,” Carmack says. “But clues such as a large gap in the births of children or Mary’s having children in her 50s or 60s would suggest a second wife entered the scene.”

For more tips on untangling your ancestors’ names, see the December 2003 Family Tree Magazine or the 2006 Genealogy Guidebook. Both are available from <www.familytreemagazine.com> and (800)258-0929.

TRAP #3: It’s not spelled like my ancestor’s name, so ft can’t be him.

Your ancestor’s name might not be spelled the way you think it should be for many reasons. The census taker or county clerk who recorded your forebear’s name may have garbled the spelling. Or maybe the genealogist who submitted your ancestor to the Web site you’re searching simply mistyped the name: Gambler rather than Gamber, Jeff rather than Geoff or Levine rather than Levin. It’s also possible someone mistranscribed the information. My grandfather Harvey Eisenstodt shows up as Harry Eisenstadt in Ancestry.com’s 1930 census database. Looking at the original record, I can tell the handwritten name is Harvey Eisenstodt, but it’s hard to make out.

Could your ancestor have changed his name, or gone by a nickname? My great-grandmother Gertrude Levinson, who was born in Poland, shows up in the 1910 census as Guslia or Gustia (again, the handwriting’s difficult to decipher), which could explain why my dad always referred to her as “Grandma Gustie.” In the 1900 census, her name looks like Gustava or Guslava. Many immigrants changed their names (first and last) to assimilate to their new surroundings. There’s a good chance your immigrant ancestors’ names evolved the way my great-grandmother’s did.

Even American-born ancestors may have changed their names or used nicknames. Women named Sarah often went by Sally; those named Margaret, by Meg or Peg. See <genealogy.about.com/library/bl_nicknames.htm> and <www.usgenweb.org/research/nicknames.shtml> for lists of nicknames and their given-name equivalents.

TRAP #4: All the children who’re listed with my great-great-grandmother are hers.

The 1860 census for Perry Township, Tippecanoe County, Ind., lists my fourth-great-grandfather Andrew Jackson Bull along with his wife, Margaret, and six children. At first glance, one would assume all of the children are Andrew and Margaret’s. But the kids’ ages range from 3 months to 18 years, and Margaret was only 30.

Through family records, I learned that Andrew married twice. First, he wed Sarah Jane Bartmess, and then, after Sarah’s death, Margaret Dickson. Sarah and Andrew’s son Robert Fulton Bull is my ancestor, which means I’m not related to Margaret by blood. This goes to show you shouldn’t assume a male ancestor’s wife is your ancestor, and vice versa. People remarried more often than you might think.

Along the same lines, don’t assume all the children listed in a given record have the same mother. As mentioned earlier, a large gap in children’s ages could suggest more than one mother. In the case of the Bull family, Sarah had three children, ages 14, 16 and 18 by 1860. Margaret’s children were 3 months, 3 years and 6 years old.

It’s not uncommon to find cousins and other relatives living in a household, too. Keep in mind that all the children listed in a given census record might not be siblings.

TRAP #5: If I have to pay to use a site, the information must be better.

Subscription sites such as Ancestry.com and Genealogy.com <www.genealogy.com> have a lot to offer, and they consistently make our annual 101 Best Web Sites list (go to the Family Tree Magazine Web site to view each year’s picks).

But so do free sites such as Family-Search, USGenWeb <www.usgenweb.org> and the Civil War Soldiers and Sailors System <www.itd.nps.gov/cwss>. Even though these digital destinations don’t charge a penny, their information’s just as good.

Surf over to Cyndi’s List <www.cyndislist.com> for upward of 250,000 links to digital destinations covering everything from Acadians, Cajuns and Creoles to wills and probates. Dedicated genealogists who want to share the wealth of their knowledge — or their genealogical libraries — can take credit for many of these sites.

The Immigrant Ships Transcribers Guild <www.immigrantships.net>, for instance, serves up more than 8,000 ship manifests, which you can search or browse. The folks behind Books We Own <www.rootsweb.com/-bwo> will do free lookups in the genealogical resources they have on hand. A number of states, libraries, archives, and historical and genealogical societies have posted free roots resources on the Internet, as well. Check out sites such as the Minnesota Historical Society <www.mnhs.org>, the West Virginia Memory Project <www.wvculture.org/history/wvmemory>, Colorado’s Historic Newspaper Collection <www.cdpheritage.org/newspapers> and the Michigan Department of Community Health’s Genealogical Death Indexing System <www.mdch.state.mi.us/pha/osr/gendisx/search2.htm>.

Just remember: No matter where you find family information — whether it comes from a pay or free Web site — you’ll need to double-check the details in original sources.

TRAP #6: It doesn’t matter whether online information comes from a record, a transcription or an index.

An online record is an original document that’s been digitized for viewing on the Web. For example, Ancestry.com has posted images of original census enumerations on its site. When you pull information from one of those images, you don’t have to worry as much about verifying the facts (though it helps to check other records, just in case).

You have to be more careful with online transcriptions, which are typed copies of original documents. These far outnumber digitized records. You’ll find transcriptions of passenger lists (on the Immigrant Ships Transcribers Guild Web site for example), tombstone inscriptions (at Find a Grave <www.findagrave.com> and Interment.net <www.interment.net>) and all sorts of other records. Just remember that typographical errors easily can sneak into transcriptions. Even a careful transcriber might not correctly read the handwriting on an original document. Always verify spellings and dates in the original record.

Online indexes, similar to book indexes, can help you find references to your ancestors in state vital records files, books, periodicals and other sources. When you locate your ancestor in, say, the Periodical Source Index (searchable via HeritageQuest Online <www.heritagequestonline.com>, which you can access free if your library subscribes), jot down all the information, and then look for the genealogical or historical journal where the data appears. Or if your ancestor’s name is in an online death-records index, note the certificate number and use it to request a copy from the state vital-records office. An index will contain only a fraction of the information recorded in the original source.

TRAP #7: My ancestor must not have lived in Any town, USA, at that time, because I can’t find him in online records there.

Not necessarily true. Your ancestor may have been out of town or living in a relative’s household when the census taker stopped by. Perhaps Great-grandpa Ebeneezer was home, but the census taker recorded his name wrong. Or maybe the person who transcribed or indexed his record misspelled the name. I didn’t find my Thuerk relatives in the 1930 census database on Ancestry.com until I searched on Thuark. Try every spelling variation you can think of. Some Web sites let you search for spelling variations automatically, using Soundex — a code-based indexing system that groups similar-sounding names. (See <www.familytreemagazine.com/soundex.html> for more information.)

Of course, it’s also possible your ancestors went by different names during the time period you’re researching, especially if they were recent immigrants. If your Polish great-grandfather was called Piotr Kraiec in the old country, you won’t find him in the Ellis Island passenger list database <www.ellisisland.org> if you search for Peter Taylor, his Americanized moniker.

Not having any luck with a US census from 1790 through 1840 or 1910? Only head-of-household indexes exist for those years. That means, unless your third-great-grandmother had her own place, you won’t find her in any of those indexes. You’ll have to search for her husband. The same goes for kids; look for their father.

Be sure you’re looking in the right jurisdiction, too. County boundaries changed often, so your family could’ve lived in different counties in 1900 and 1910, even if they didn’t move an inch. Or say your grandfather lived his whole life in Cincinnati, but you can’t find evidence he wed your grandmother. Could they have gotten married in her hometown across the Ohio River? Try looking for a Kentucky marriage license.

TRAP #8: If I search hard enough, I can find all the family information I need on the Web.

Unfortunately, that’s not always the case. As I’ve learned while trying to research my Eisenstodt family, the Internet will get you only so far. I’ve found my Eisenstodts in the 1930 census and in the Social Security Death Index (you can search several versions of this index at <www.stevemorse.org/ssdi>), but that’s about it. I’m sure the Eisenstodts created all the usual records, but no one’s bothered to post them online yet.

When the records — such as birth, death and marriage certificates, naturalizations, wills, immigration and land records, and more — on your family aren’t on the Web, you’ll still need to pound the pavement and actually visit research repositories. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ Family History Library (the folks who’ve brought us FamilySearch) in Salt Lake City and the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) <archives.gov> in Washington, DC, are two well-known repositories. Each has local or regional branches; check their Web sites to find a location near you. Most large libraries have genealogy collections — try those in your and your ancestor’s hometown. Also visit historical societies, state archives and county courthouses. Turn to page 6 for more advice on finding your relatives’ records.

TRAP #9: They’re my family; Information about them belongs to me.

Not so fast. While you have every right to take pride in your family tree, you can’t claim rights to facts such as names, dates and places. If you post your grandfather’s birth date and place online, anyone can use that data for his or her own research without asking your permission. If you write a narrative about Grandpa and post it to your Web site, though, you own the copyright to your description of family information because it’s considered an original work. Copyright also protects books, diaries, photographs and maps — but only those published since Jan. 1, 1923. Works published before that date are in the public domain.

Copyright doesn’t cover government-generated records such as birth certificates, military service records and census schedules, though privacy restrictions may apply to more recent documents. Copyright does, however, cover compilations of facts. Although the subscription Web site Ancestry.com doesn’t own the actual genealogical data it serves up — no one does — it does own the databases that help you find that information.

Generally, when you submit a GEDCOM file (the universal family tree file format almost all genealogy software recognizes) to a pedigree database such as Ancestry World Tree, you must agree to allow the Web site owner to sell or publish that information. When Ancestry.com developed its subscription service OneWorldTree <www.ancestry.com/trees> a couple of years ago, a lot of researchers were steamed because they thought Ancestry.com was profiting from their work. They’re right — to a certain extent. OneWorldTree is a search engine that efficiently sorts through genealogists’ family files in Ancestry World Tree. But since no one owns those genealogical facts — and Ancestry.com developed OneWorldTree all on its own — it has every right to charge a fee for its use.

For more information about the ins and outs of copyright, see the December 2004 Family Tree Magazine or Carmack’s Guide to Copyrights & Contracts: A Primer for Genealogists, Writers & Researchers by Sharon DeBartolo Carmack (Genealogical Publishing Co.).

TRAP #10: The Internet’s the best place to begin researching my family history.

These days, we use the Internet for everything from finding a phone number to reading up on what car to buy. It’s natural to hop online the minute you decide to trace your family tree.

Though any veteran genealogist will tell you to start your family history research at home, you shouldn’t start at your home computer. Before you get online, hunt in your attic, basement and closets for home sources — birth, marriage and death certificates; photographs; letters; family Bibles; and other records normally kept in the home. If you don’t find anything at your house, ask relatives. Your mom might have her dad’s military discharge papers or a cousin could be guardian of the family Bible that lists birth, marriage and death dates for several generations. Sit down with your relatives and talk about the past, too. Besides names and dates, they might have some fascinating stories that give you insight into your ancestors’ personalities.

Once you’ve investigated home sources and talked to relatives, turn to the Internet with questions that came up. If you learn an ancestor fought in the Civil War, try filling in the details using the Civil War Soldiers and Sailors System Web site. Don’t forget to avoid trap #8: You still need to verify online facts, and sometimes the information you need won’t exist on the Web — as I’ve found with my Eisenstodt family — so you’ll have to turn elsewhere for answers. Take advantage of libraries, archives, and historical and genealogical societies. You’ll have plenty of rime to do so now that you’re prepared to nimbly sidestep potential research pitfalls as you fly down the information superhighway.

From the issue May 2006 issue of Family Tree Magazine.