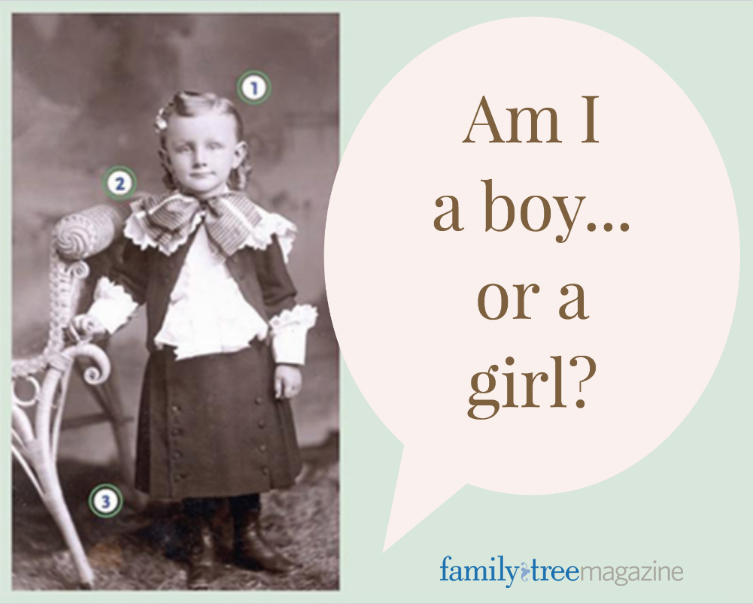

Watch out for these three clues:

1. Parting ways. Boys’ hairstyles were parted on the side, as shown here; girls wore their hair parted in the middle.

2. Trend watch. Compare outfits to fashion reference books and adult clothing. This boy’s Little Lord Fauntleroy look dates to the 1890s.

Hair it is

Many a genealogist looks at a photo, sees a skirt and long hair on the subject, and immediately — often incorrectly — concludes it’s another picture of Great-grandma Mabel. But looks can be deceiving, so rely on this identification tip that’s so simple it’s hard to believe: Check out where the child’s hair is parted. Mothers parted their daughters’ hair in the center and their sons’ hair on the side. (For the record, the child shown on this page is a boy.) When boys reached school age, they usually started sporting shorter haircuts.

Wear apparent

A quick glance at a fashion tome such as The Child in Fashion 1750-1920 by Kristina Harris (Schiffer Publishing) shows you can’t rely on short hair and pants to pinpoint boys. Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, babies of both sexes wore long dresses until they learned to walk. Thereafter, moms dressed those restless toddlers in skirts that were short enough to let them motor around. Diaper changing and toilet training were easier in these outfits, too. School-age children are simpler to identify in photos — that’s when boys and girls began wearing distinctive attire.

Junior’s clothing usually mimicked designs for women’s dresses. That means you can date kids’ outfits by comparing them to significant ladies’ fashions from the same period, such as the bolero jackets of the 1860s and the pointed bodices of the 1840s. Also use the following childhood fashion trends, which Joan Severa describes in Dressed for the Photographer: Ordinary Americans and Fashion, 1840-1900 (Kent State University Press): During the 1840s, young boys and girls “both wore dresses, either the frock type or ones with set-in belts and full skirts, although little boys sometimes wore full-length dark ‘trowsers’ under the frock.” From the 1850s through the 1880s, boys’ dresses came in tartan plaids or featured military trim, which differentiated their clothing from their sisters’.

Outfit for a prince

In this 1890s photo, the boy poses in a skirt, short jacket, ruffled shirt and large bow similar to the velvet suits first seen during the 1860s. This is a feminine look by modern standards, but it became wildly popular for boys when author Frances Hodgson Burnett published her children’s novel Little Lord Fauntleroy in 1886. The velvet knickerbocker suit with a lace Van Dyke collar and broad sash turned into a persistent fashion trend that forever after was associated with Burnett’s main character.

Eventually, the Little Lord Fauntleroy look encompassed all velvet suits (including those with pants) and any suit with a lace collar.

Aging well

In addition to noting gender-related fashion details, try to estimate the child’s age by examining his clothing. Here’s your basic rule: Boys wore long white dresses until about age 3, and short skirts until they turned 5. School-age boys dressed in knee-length pants until around age 12, when they donned long trousers like their fathers’. The boy shown above is probably 3 to 5 years old — the photographer who took his portrait captured his pride at wearing “grown-up” attire.

Prop yourself up

If you still have any doubts about the sex of the child in your picture, look at the props. Photographers kept toys on hand to occupy fidgety tots, and the selections were pretty stereotypical — it’s a safe bet a wagon means the subject is a boy, and a doll indicates a girl.

Now you know it’s a snap to tell boys from girls in vintage photos. After you decide who’s who, date fashion trends and compute the child’s age, rely on other factors, such as the type of image (daguerreotype, tintype, photo postcard) and your genealogical data, to verify the time frame. No more mixing up family photos of Bert and Ethel: With this discriminating advice, you’ll make the right ID.