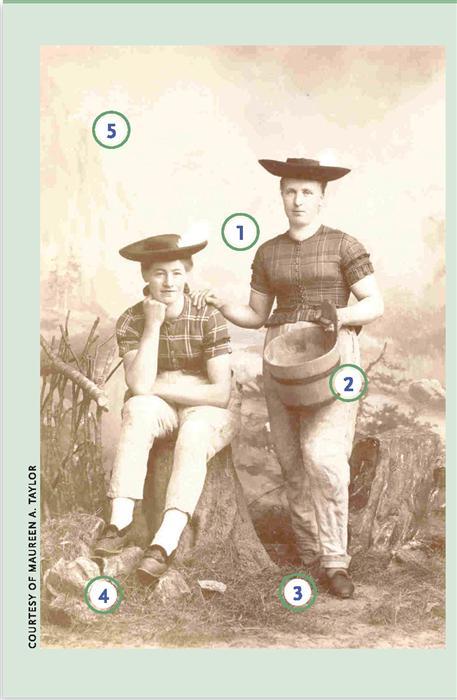

Face it The hoop skirts, bustles and corsets our female ancestors wore most of the time weren’t exactly comfortable, especially for active pursuits. In Women in Pants: Manly Maidens, Cowgirls, and Other Renegades (Abrams), Catherine Smith and Cynthia Greig explain why genteel ladies of the past—such as the pair pictured here—sometimes donned men’s clothes. From the early feminists of the 1850s to Calamity Jane in the 1890s, photos prove women wore bloomers, knickerbockers, breeches, pantaloons, pants and trousers.

Pants were outside the norm for 1800s and early 1900s ladies, though, so a fashion encyclopedia might not help you interpret a portrait of Great-aunt Nell sporting the latest in trouser wear. Instead, learn about your female relative by using other photo details and focusing on the interests and activities her legged outfit reveals.

Pretty political

Clothing reflected our ancestors’ economic status, personality and, for women’s rights advocates such as Amelia Bloomer, their politics. In 1851, Bloomer began publishing articles in her biweekly newsletter, The Lily, advocating less-confining clothing for women. In place of their heavy dresses and restrictive undergarments, Bloomer wrote, ladies should wear shorter skirts over ankle-length pants (a garment eventually named for its proponent). A few brave early feminists, including Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, embraced bloomers, but the style faded around the end of the decade. Several different types of photographs existed during the 1850s, so look for a photographer’s name (called an imprint) on the back of a paper print, or embossed in the brass mat of a cased picture. Then look up the business in city directories and consult your research to see who lived in the area at that time.

Secret service

Mary Livermore, who headed the Midwest area of the US Sanitary Commission during the Civil War, estimated more than 400 women disguised themselves as men to enlist. Perhaps the female soldiers agreed with Medal of Honor recipient Mary Walker, one of three women surgeons known to have served the Union, who declared, “Patriotism has no sex.” Such convictions weren’t confined to the Civil War: Until women were officially allowed to join the armed services, they infiltrated the ranks in all wartime conflicts. Some managed to remain undetected; others were sent home once injured and discovered. These soldiers carefully concealed their identities, and many are indistinguishable from men in photographs. Maybe you have Civil War photos but no male relatives the right age, or the soldier pictured bears a strong resemblance to a female ancestor’s portrait. If you suspect your soldier is really a woman, pay attention to family folklore, look for military records (see the October 2005 Family Tree Magazine for research advice) and read Richard Hall’s Patriots in Disguise: Women Warriors of the Civil War (Paragon House, out of print).

Good sports

In the late 19th century, special bifurcated costumes, practical for recreational activities, offered women acceptable alternatives to wearing their husbands’ altered clothing. All sorts of legged costumes became fashionable for horseback riding, gymnastics, swimming, bicycling and tennis. Compare clothing in your photos with the examples in Smith and Greig’s book and in American Dress Pattern Catalogs, 1873-1909 edited by Nancy Villa Bryk (Dover Publications).

Business casual

Women engaged in farming, ranching, painting and carpentry found pants comfortable for doing “men’s work.” In England, women who worked in mines donned men’s attire for safety and ease of movement. Unlike men, however, women often complemented their pantaloons with simple accessories, bodices reminiscent of dresses and, as the two ladies in the photo above demonstrate, hats to shade their faces from the sun. Honing in on those details gives you more clothing evidence to work with. The exact occupation of these women is unclear but their bucket, large-brimmed hats and flat shoes suggest an outdoor endeavor.

Sometimes, dressing in men’s clothing was scandalous but reasonable. When Katherine Hepburn and Marlene Dietrich wore pants in the 1930s, they were taking cues from theater mavens such as Sarah Bernhardt, who often played male roles.

Getting a Leg Up

Clothes call. These feminine fitted bodices with minimal trim date from the 1880s.

Professional advice. Some props, such as the one-handled bucket in this photograph, are occupational clues.

Fancy footwork. Compare shoes to the descriptions in Nancy E. Rexford’s Women’s Shoes in America, 1795-1930 (Kent State University Press).

Background information. During the 1880s, photographers often decorated their sets with props such as wooden fences, rocks and hay.

Twenty questions. Asking family members about unusual photographs may be the best way to get the scoop.

From the February 2006 issue of Family Tree Magazine.