Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

You spend hours searching the silent faces in your old family photos, trying to tease out some meaning: What are their names? Why did they pause to pose for the camera — and when was it, anyway? But how often have you wondered who was holding the camera? The identity of the photographer — be it a professional, family member or friend — could be the key to answering those who, what, when and where questions you’ve been asking. The strategies here can help you learn who snapped the photos of your kin, and what he or she has to say.

You spend hours searching the silent faces in your old family photos, trying to tease out some meaning: What are their names? Why did they pause to pose for the camera — and when was it, anyway? But how often have you wondered who was holding the camera? The identity of the photographer — be it a professional, family member or friend — could be the key to answering those who, what, when and where questions you’ve been asking. The strategies here can help you learn who snapped the photos of your kin, and what he or she has to say.

Historical snapshot

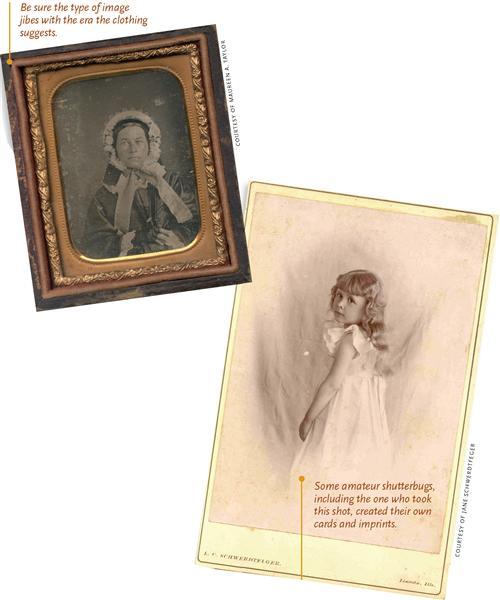

First, let’s take a quick look back at how the photography trade has developed. Before the camera came along, time-consuming paintbrush and charcoal were the only ways to capture family — faces on paper. After the 1839 introduction of the daguerreotype — called a “mirror with a memory” because of the metal image’s reflective surface — anyone could visit a photographer and leave with his likeness for a fraction of the cost of a painted portrait.

Early photography encompassed an array of image types: daguerreotypes, ambrotypes on glass, tintypes on iron, and paper prints. From 1840 until the 1880s, most images were taken by professional photographers in studios, or by itinerants who traveled rural areas with their equipment. Photographers came from all walks of life — some operated formal studios; others were merchants who — added studios to their stores for extra income.

ADVERTISEMENT

Kodak founder George Eastman revolutionized photography in 1888 when he offered amateurs a box camera pre-loaded with enough film for 100 pictures. His slogan “You push the button, we do the rest” says it all: Users simply sent the whole camera back to the factory for developing, printing and reloading. Men took most pictures in the first decades of photography, but Kodak advertised its box camera to women and children. In 1900, the company’s new, $1 Brownie camera was an instant hit, with a quarter of a million sold that year. This easy-to-operate camera suited children especially well. By the end of the 19th century, the photography scene had shifted: People took their own pictures to capture their everyday lives, and hired professionals only for special occasions — much as we do today.

Photographic positives

Learning about yesterday’s photographers sounds interesting enough — but how does it apply to your family history? Think of it as a back-door genealogy method: Just as studying siblings and cousins can lead you to answers about your ancestors, looking behind the lens can direct you to new discoveries about the people in your photos. This research can pay off by letting you:

ADVERTISEMENT

? Put your ancestors in a place and time. The photographer’s name and address in a photo imprint (see the next section for more on imprints) is evidence of where your ancestors posed. You also can find out when the studio was in business to hone in on a date for the photo (but watch out for the potential photo-dating pitfalls at right). Determine a photo’s date and location, and you might be able to guess the occasion. A graduation, say, could point you to undiscovered genealogical sources, such as school records.

? Find more photos. You’re probably not the only descendant who inherited family pictures. If you can identify which shutterbug to thank for the contents of your photo shoe-box, you can contact other relatives to ask about their picture caches. You might meet a whole new generation or two as captured by your clan’s own photographic enthusiast.

? Gather family stories. The same descendants who have family photos might be able to provide IDs and stories to go along with them. Even if you don’t definitively figure out who took a snapshot, you can make a good guess. Was it a newborn’s proud papa? A wistful mom on her youngest child’s first day of school (as suggested by the metal lunch-box)? The answers let you stand in your ancestors’ footsteps and imagine them as people, rather than names and dates — good material for journaling in your scrapbook or writing about in your family history book.

? Get social history clues. The photography studio your ancestors used might indicate their cultural backgrounds and economic status. Photographers located in ethnic neighborhoods may be your ancestors’ countrymen. A foreign-language imprint on a photo taken in the United States is a clue to immigration.

Fierce competition among professional photographers spurred them to display pictures of famous clients, so posing for a prestigious photographer showed off one’s social standing. Prominent Boston families visited one of the country’s first photography studios, Southworth & Hawes; later, they also used Bachrach. In England, Notman photographed well-known individuals; in Washington, DC, notable people posed for Mathew Brady. Newspapers acting as 19th-century versions of “Entertainment Tonight” printed the names of celebrities in town, as well as what they did and where they sat for portraits. Your well-heeled ancestors may have modeled in the same chair as songbird Jenny Lind or businessman John Jacob Astor.

Clues in a photo’s props and setting can supplement the economic-status details you’ve learned from ancestors’ census, tax and probate records. Photographers offering low-cost portraits may not have used the most fashionable accessories or set up shop in the best neighborhoods. Costume encyclopedias such as John Peacock’s Fashion Accessories: The Complete 20th Century Sourcebook (Thames and Hudson, $34.95) show trendsetting styles of different eras. Newspapers and local histories can give you a sense of the most affluent areas of town.

Professional help

Since photography didn’t become a mass-market endeavor until the late 1880s, pros would have taken most of your 19th-century photos. Luckily, you’ll find plenty of tools and resources to trace those tradesmen. You can call on your genealogical sleuthing skills, too. First, look on the image for a name and/or an address. This mark is called an imprint — and it’s a clue worth getting excited about. (See examples of imprints on page 30.) Not all photographers left such evidence, especially on cased images such as daguerreotypes, ambrotypes and tintypes. A photographer might have scratched his name into the case’s metal exterior or cover glass, etched it onto the brass mat or embossed it on the velvet interior. Photographers sometimes inserted business cards behind the cased image to identify their work. Imprints on card photographs (paper prints mounted on cardboard) may be stamped, embossed or handwritten on the mat or on the card itself.

Cautionary dating tales

Relying on just one photographic detail, such as an imprint, can lead you to inaccurately date your photo. Before you draw conclusions, add up and compare all the available clues (see the February 2005 Family Tree Magazine for examples). And watch out for these four photo-identification pitfalls:

? Duplicate images: The photographic method — daguerreotype, tintype, paper print — often can help you estimate a picture’s date. But don’t be fooled by reproductions. When the costumes, props or captions don’t correspond to the medium (such as an image of your flapper grandma on Kodak Gold paper), you’re likely dealing with a copy.

? Out-of-context clues: Assess whether the dates on an imprint fit the time frame indicated by other clues, such as clothing styles. If they don’t, you might own a photo that’s been inserted into another photographer’s enclosure.

? Publisher’s imprints: An imprint doesn’t always refer to a photographer; it may show the name of a publisher or distributor instead. For example, publishers occasionally reproduced card photographs of famous people, such as royals or Civil War heroes, to sell — and they printed their company name on the copies.

? Amateurs playing pro: A friend of mine possesses several imprinted photos taken by one of her ancestors. It turns out her relative was a banker who dabbled in photography and imitated professionals by mounting his photographs — such as the one at right — on cardboard with pre-stamped imprints.

The simplest imprints feature just a studio name or photographer’s initial. Others identify the name of the studio and photographer, or the publisher who reproduced and sold photo cards. More-elaborate imprints might contain a list of the photographer’s services and awards, along with his logo. Once you’ve gleaned as much information as you can, consult these sources to find out when and where the photographer worked:

?Web sites: Type the photographer’s name into a search engine such as Google <www.google.com>. Besides biographical data, you may find collections of his images — especially if you turn up a museum catalog or online finding aid with his name. You also can pose questions on message boards and mailing lists.

? Directories: In most parts of the country, annual directories listed businesses and residences by locality, region, business or house — much like today’s phone books. If you know a photographer’s name and hometown, but not the specific address, consult city directories published around the time you suspect the photo was taken. Listings typically show people’s names and addresses, occupations and often their employers. Can’t pinpoint a town? Try verifying the photographer’s location in regional and suburban directories, which cover wider geographic areas. (While you’re browsing, don’t forget to check for mention of your kin.)

Business directories — containing information on companies large and small — help when you know the photography studio’s name, but not who owned it. If the imprint gives you only an address, look it up in a house directory to find the business or residence at that location. Most of these directories have alphabetical street indexes (or separate volumes) that list occupants by house or building number.

If you live near a large public library, give the reference desk a call — it may have directories covering other areas. Otherwise, ask a library or historical society near the studio’s location whether it holds directories and whether you can borrow them via interlibrary loan. Consider yourself lucky if you’re close to the Library of Congress <www.loc.gov> in Washington, DC, or the American Antiquarian Society <www.americanantiquarian.org> in Worcester, Mass.: They have the country’s largest directory collections.

? Photographer finding aids: To see if a directory of photographers exists for your area, consult the international compilation of such works in Photographers: A Sourcebook for Historical Research (Carl Mautz, $25) edited by Peter Palmquist. Visit Finding Photographers <www.findingphotographers.com>, an online clearinghouse of photographer lists, too. The George Eastman House <www.geh.org>, an international photography museum, has an online database that’s searchable by photographer, location, subject and photographic process. Some listings contain sparse information, but they do help you place a photographer in a specific place at a specific time. It’s also worth checking with the local or state historical society where your photographer worked.

? Mug books: These collections of biographical sketches — also called booster books — profiled prominent individuals (who often often wrote their own biographies). If he was well-established, the photographer you’re looking for may be one of them, and his profile also might outline the history of his studio.

? Census records: Look for the photographer in federal and state census records to establish when he was in business — those dates narrow the time frame for your photo. Don’t be misled if the census lists another occupation for a likely suspect, particularly in the early years of photography. Photographers often stated their occupation according to the process used — tintypist, daguerreotypist, ambrotypist — or identified themselves as artists. People with multiple trades had to select just one for the census taker. Look for census records at large public libraries, the Church of Jesus Christ of

Latter-day Saints’ Family History Library <www.familysearch.org> in Salt Lake City (or one of its branch Family History Centers), and on subscription Web sites Ancestry.com <Ancestry.com > and Genealogy.com <www.genealogy.com>. See the April 2005 Family Tree Magazine for other online census sources (including free sites).

Special “nonpopulation” censuses, such as the 1850 to 1870 industrial schedules and 1880 manufacturing schedules, recorded photographers. These enumerations compiled information about manufacturing, mercantile, commercial and trading businesses that had gross annual incomes higher than $500. Listings give the name of the business or owner; amount of capital invested; and quantity and value of materials, labor, machinery and products. You can get these special censuses through various repositories, including the National Archives and Records Administration <www.archives.gov> and state archives. See a list of available schedules in Uncovering Your Ancestry Through Family Photographs, revised edition (Family Tree Books, $21.99).

? Social histories: Ever wonder how your relatives sat so still for the camera? Enhance the stories behind your portraits by reading about the equipment yesterday’s photographers used — including immobilizing waist clamps and neck braces. You can learn these historical tidbits in The Photographic Experience, 1839-1914: Images and Attitudes by Heinz K. and Bridget A. Henisch (Pennsylvannia State University Press, $128.95).

Pros in Your Pedigree

Have you discovered a professional photographer in your family tree? You could turn up collections of his work in a museum or historical society. To learn more about him and his photos, follow the basic steps for researching any professional shutterbug (see page 32). Start by plugging his name into an online search engine such as Google <www.google.com> and contacting museums and historical societies in the area where he worked.

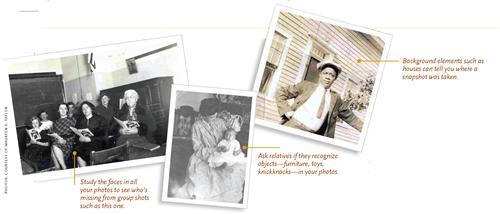

Whether you locate your pro’s pics in an archive or a family collection, be sure to inspect the images for further clues. Identical backdrops, props and costumes in a set of photos could mean they were taken on the same day — and the people pictured may be related. Look for sequential negative numbers on the backs of the images, as well.

Prints may bear the statement “Negatives retained.” Don’t get too excited — the corresponding negatives probably were discarded when the photographer died. But just in case someone saved them, search for leads online and check with historical societies.

Occasionally a photographer’s prints and equipment stayed with his family after his studio closed — perhaps the collection is tucked away in a distant relative’s attic or basement. Track down other descendants and ask what happened to the relics of the business. If you own such a collection of materials, preserve it by donating it to an archive.

? Newspapers and magazines: Newspapers often carried photographers’ advertisements, business news items and obituaries. Occasionally, a newspaper would run a story on a local studio, especially if someone famous had a portrait taken there, or the photographer started using a new process. Once I was looking into the Manchester Brothers studio of Providence, RI, and stumbled across a newspaper interview in which an assistant recounted the entire history of the firm. You may be able to get microfilm of the photographer’s local newspaper through interlibrary loan. Unless the newspaper is indexed, though, save this labor-intensive search until you’ve exhausted your other research options.

If a photographer’s imprint lists an award or a patent for a new technique, look for related magazine articles using William S. Johnson’s Nineteenth-Century Photography: An Annotated Bibliography, 1839-1879 (G.K. Hall) — it’s out of print, but available in large libraries. See the April 2004 Family Tree Magazine for help researching a patent, which can narrow the date a photo was taken.

Amateur hour

Kodak’s first box camera ushered in the era of relatives and friends taking pictures. I clearly remember my seventh birthday, when my mom gave me a camera that turned me into the family shutterbug. Similarly, at a recent workshop I conducted with senior citizens, almost everyone recalled the thrill of that first camera. Few could say whatever happened to their photos, but all remembered whom they photographed and why. It’s a safe bet many of your pictures were taken by people like them — moms, grandmas, uncles and cousins. Try these tips to figure out who was behind the camera and when:

? Get a date. Knowing the date the picture was taken lets you narrow your list of photo-snapping suspects to relatives alive at the time. The step-by-step photo-identification worksheet in the May 2005 Trace Your Family History, a special issue of Family Tree Magazine, helps you date your photos by using characteristics such as the type of photo, clothing and photographer’s props. See my Photo Detective columns for specifics on analyzing subjects’ clothing and hairstyles — for example, ladies’ hats with large feathers were fashionable during the 1890s.

The size and shape of the print itself aren’t reliable dating clues because manufacturers still offer film for older cameras as new models debut. But those details can give you a beginning date by telling you when the camera that took the pictures was produced. Early Kodak and competing models produced prints in a variety of sizes and shapes. You can find a list of early box cameras online at BoxCameras.com <www.boxcameras.com>, along with information on their manufacturers, prints and negatives. An inventory of Kodak films and print sizes appears in Brian Coe’s Kodak Cameras: The First Hundred Years (Hove).

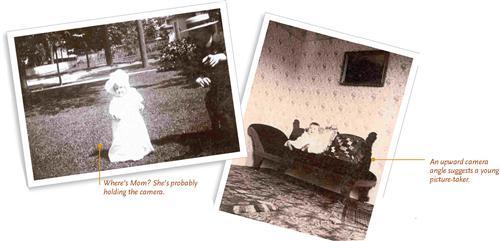

If a photo predates the box camera’s 1888 debut, a relative probably didn’t take it. With few exceptions (see opposite), most people didn’t own cameras or studio equipment.

? Identify missing persons. Obviously, the people in the photo didn’t click the shutter, so check all your pictures to see who’s absent. For instance, the toddler on the opposite page (left) probably was photographed by his mother — assuming that’s Dad gesturing to get Junior’s attention. If a picture shows a group of siblings, which one isn’t there? Examine your albums to see who rarely shows up in the pictures. If you can identify a consistently missing person, you may have found the family photographer. Now you can concentrate on finding photos of that person.

? Guess their ages. The camera angle hints at the photographer’s age: Children tend to shoot upward; adults, downward or at eye level. To capture the oddly angled shot on the opposite page (right), a friend or sibling may have aimed the camera while seated on the floor. If the camera’s pointed up and only three of a family’s four children are standing with Mom and Dad in the photo, you might just have identified your picture-taker.

? Study captions, props and setting. Don’t forget to carefully read photo-album captions and turn over all your pictures to look for notes on the back. Verify whatever information you find, since you can’t be sure who wrote the words and or how the labeler got her information.

Study the snapshot for revealing details, such as other photographs, furniture and toys. If you see Great-aunt Alice’s Shirley Temple doll sitting on a sofa you know was purchased in the ’40s, you can guess which family owned the photo and when. Since early snapshot cameras lacked built-in flashes, subjects often posed outdoors, as the man shown above (right) did. Ask relatives if they recognize houses in the background, and use antique-car books to date vehicles.

Investigating your photographs based on what’s depicted in the image is just one way to uncover the family information they contain. Peer behind the camera at the professional or family photographer who clicked the shutter — that faceless person may hold the answers to your photo mysteries.

TOOLKIT

WEB SITES

? Craig’s Daguerreian Registry

? Early St. Louis Photographers

<genealogyinstlouis.accessgenealogy.com/photography.htm>

? EdinPhoto — Professional Photographers 1840 to 1920

<www.edinphoto.org.uk>: Click “Profess Photog.”

? Finding Photographers

<www.findingphotographers.com>

? George Eastman House

? History of Kodak Roll Films

<members.aol.com/chuck02178/film.htm>

? Index of Victorian, Edwardian and Early 20th-Century UK Photographers

<www.users.waitrose.com/~rodliffe>

? Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Online Catalog

<lcweb2.loc.gov/pp/pphome.html>

? Nineteenth Century Photography — A Timeline

<www.victorianweb.org/photos/chron.html>

BOOKS

? American Photographs: The First Century by Merry A. Foresta (Smithsonian Institution Press)

? Biographies of Western Photographers 1840-1900 by Carl Mautz (Carl Mautz Publishing)

? Black Photographers 1840-1940: An Illustrated Biobibliography by Deborah Willis-Thomas (Garland)

? Catching Shadows: A Directory of Nineteenth-Century Texas Photographers by David Haynes (Texas State Historical Association)

? Collector’s Guide to Early Photographs by O. Henry Mace (Krause Publications)

? Directory of Massachusetts Photographers, 1839-1900 by Chris Steele and Ron Polito (Picton Press)

? Directory of Pennsylvania Photographers, 1839-1900 by Linda Ries and Jay W. Ruby (Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission)

? Directory of Photographers in the United States 1888 & 1889 and Canada 1889 by Diane VanSkiver Gagel (Heritage Books)

? International Guide to Nineteenth Century Photographers and Their Works: Based on Catalogues of Auction Houses and Dealers (Art) by Gary Edwards (G.K. Hall)

? Ohio Photographers, 1839-1900 by Diane VanSkiver Gagel (Carl Mautz Publishing)

? Photographers: A Sourcebook for Historical Research, edited by Peter Palmquist (Carl Mautz Publishing)

? Photography and Photographers to 1900: An Annotated Bibliography by Robert S. Sennet (Garland, out of print)

ORGANIZATIONS

? The Daguerreian Society

3043 W. Liberty Ave., Pittsburgh, PA 15216, (412) 343-5525, <www.daguerre.org>

ADVERTISEMENT