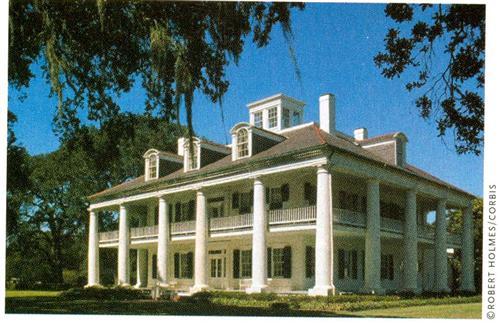

In the geography of our imagination, the South is as constant as a Moon Pie. Forever under fluttering Stars and Bars, the stereotypical land of cotton is a drawling amalgam of Gone with the Wind and “The Andy Griffith Show,” To Kill a Mockingbird and the Grand Ole Opry, In the Heat of the Night and Inherit The Wind, bound together with grits and washed down with a cool mint julep out on the veranda, y’all. In the popular mind, Southern history began at Fort Sumter and ended when the Dixie of George Wallace gave way to the New South of Ted Turner.

But if you go looking for your Southern ancestors in Tara, you’re likely to be disappointed. The reality of the South is much more complex than those stereotypes. Indeed, if you try to trace your Southern roots back more than three or four generations, you’ll find pioneers and Indians and families headed west — the frontier South of Daniel Boone, where the fever for land was hotter than Atlanta in August. Change was the constant here, with populations on the move and state and country borders melting like ice cubes in sweet tea.

I always thought of my maternal ancestors, for example, as being strictly from Alabama, where my mother grew up. But our family tree actually runs from Virginia to North Carolina to South Carolina, with off-shoots in Georgia, before becoming firmly planted in the red dirt of Alabama.

Even the definition of “the South” isn’t as solid as the Mason-Dixon line. That famous boundary, after all, put Maryland and Delaware down South — yet neither seceded and we think of both now as “mid-Atlantic states.” Kentucky was a “border state” during the recent unpleasantness, but its settlement patterns are deeply Dixie. Certainly “the South” encompasses the 11 states of the Confederacy, yet Confederate Texas has a split personality, both Southern and Western.

First Steps Southward

So where do you start in this surprisingly complicated region? Like any genealogical quest, Southern genealogy begins in your own backyard — start with sources in your own home and family, then work backward from today, one step at a time. Emily Croom, author of the best-selling Unpuzzling Your Past (Betterway Books) and an expert on Southern roots, advises, “Each family has its own starting point in Southern research. For those families still in the South, the starting point of research is where they are now. For those families no longer in the South, that starting point is when they left the region.”

For many families who left the South, Croom says, the trigger was World War II military service or postwar job opportunities. Others moved away a few years earlier, seeking relief from the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the lure of cities replaced the promise of cheap farm land, tugging families away from the South, which remained heavily rural.

So your first challenge is to learn when, where and why your individual ancestor or family moved to a city, left the South, or chose to remain in the rural South. Interview family members and pore over family papers. Consult city directories and the federal censuses from 1920 backward; many states also had state censuses that can supplement or fill the gaps in federal enumerations. Study vital records beginning with the most recent birth, marriage and death certificates.

Once you’ve identified your ancestor’s last known Southern location, learn all you can about that state and even that county. Guides such as Ancestry’s Red Book (Ancestry), The Handybook for Genealogists (Everton Publishers) and The Source (Ancestry) will help you locate specific resources for your family’s part of the South. Also search the Family History Library’s catalog <www.familysearch.org/Eng/Library/FHLC/frameset_fhlc.asp> for state and county records, which you can often borrow through your local Family History Center.

Planting Tobacco, Rice, Roots

As you work your way back from your last known Southern ancestor into the past, you’ll stumble over some special challenges and puzzles; to get past them, it helps to know a little history.

Just as New Englanders proudly trace their roots to the Mayflower, the story of Southern families starts with the arrival of 105 settlers in Jamestown, Va., in 1607 — well before the Pilgrims. In 1617, these nascent Southerners shipped their first tobacco back to England, starting an economic boom that would make wealthy Virginia the envy of other colonies. By 1700, Virginia already boasted 58,000 people.

The restoration of the British monarchy in 1660, with Charles II, sparked a second wave of colonization. The crown gave a land grant to eight supporters who became the Lords Proprietors of the new colony of Carolina (from the Latin for Charles) in 1670. What tobacco was to Virginia, rice eventually became to Carolina, beckoning immigrants from the English colony of Barbados who emulated that island’s plantation economy. French Huguenots also came beginning in the 1680s, seeking religious freedom. By 1730, the population in the Charleston area alone had reached 30,000.

North Carolina saw tentative settlements even before 1650, when it was dubbed Albemarle, but didn’t really take off until 1691, when settlers from Virginia arrived and renamed it. That migration set the pattern for the next century and a half, as settlers pushed ever west and south in search of land and opportunity. Huguenots and Swiss Protestants came as well, and by 1730 North Carolina had 30,000 colonists.

The last of the Southern original colonies (apart from the arguable Maryland and Delaware) was Georgia, chartered in 1732 with an unusual two-pronged mission: to serve as a barrier against Florida, which Spain had settled way back in 1565, and to welcome debtors and other castoffs from mother England. James Oglethorpe landed at Savannah with the first 115 settlers in 1733. In Georgia’s early years it did attract 1,800 “charity colonists,” along with a number of Scots and Germans, but the colony never quite lived up to its original intent, and Georgians envied the prosperity of neighboring South Carolina. By 1752, with little more than 5,000 people, Georgia dropped its charter and became a royal colony.

If your ancestors stopped in one of these original colonies or you can trace them back to Virginia, the Carolinas or coastal Georgia, you can tap a wealth of genealogy resources dating to colonial times. Genealogical Publishing Co. <www.genealogybookshop.com>, for example, has published dozens of highly specific compilations such as Virginia Northern Neck Land Grants, 1694-1742 and South Carolina Marriages, 1688-1799. Many of these can be found in larger public libraries. The richness of colonial records is also reflected in the CD-ROMs from Genealogy.com <www.genealogy.com>, such as Colonial America, 1607-1789 Census Index (#310), and in the databases at Ancestry.com <Ancestry.com >.

Of course, these original states were also included in the very first US census, in 1790, but those records for Virginia and Georgia were burned in the War of 1812 (as were censuses for the future Southern states of Kentucky and Tennessee).

Your Southern colonial ancestors may also have fought in the Revolutionary War (though not necessarily on the winning side!). These military records are available on microfilm from the Family History Library and the National Archives <www.nara.gov>. The Daughters of the American Revolution maintains a library of 160,000 books, 300,000 genealogical files and 60,000 microforms in Washington, DC. You can search the catalog online at <www.dar.org/library/onlinlib.html>.

The Really Old West

If your ancestors pushed on beyond the colonial South, try picturing them not so much as characters from Gone with the Wind as the pioneers following Daniel Boone in George Caleb Bingham’s famous painting of crossing the Cumberland Gap. They were motivated by an impulse later called “manifest destiny,” succinctly expressed by Boone as: “Now is the time to secure all this country; we’ve got it, let’s keep it!” Land lured 18th-and early 19th-century Southerners as powerfully as gold later called people to California.

First they settled the western parts of the original colonies. Your Scotch-Irish ancestors may have settled the rolling, forested Piedmont of Virginia; some moved south from Pennsylvania in the mid-1700s, while others arrived directly in Southern ports and headed west. Your German ancestors may have headed for the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia or for the area near Salem, NC. Other settlers took advantage of land bounties for veterans of the French and Indian War.

After Boone and others brought back word of the riches to be found in Kentucky and Tennessee, settlement rapidly pushed farther west. One early settler, upon seeing Kentucky, described, “So Rich a Soil, Covered in Clover in full Bloom, the Woods alive in wild game.… It appeared that nature in the profusion of her Bounties had spread a feast for all that lives.” Those who hadn’t yet found their fortune in the original colonies found those “Bounties” irresistible. In early 19th-century Virginia, if you asked after the whereabouts of a man it was common to get the answer, “He’s gone to hell or Kentucky.”

Land speculators fueled the expansion, as did land bounties offered to North Carolinians and Virginians who fought in the Revolutionary War. If your North Carolina ancestor served as a private, he got 600 acres out West; if a colonel, 7,000 acres or more.

By 1783, Kentucky already had 12,000 people. After statehood in 1792, the population expanded from the “bluegrass country” around Lexington southward and westward, fueled first by state homestead acts and then by tobacco farming. Tennessee followed into statehood in 1796.

Historian Frank L. Owsley Sr. likened the settlement pattern itself to genealogy: “The Carolinas settled Georgia and, with considerable aid from Virginia, settled Tennessee. The remainder of the states of the Lower South were the children and grandchildren of the Carolinas, Georgia and Tennessee.”

Indian treaties and displacements, soil exhaustion in the east, public land sales and the invention of the cotton gin all combined to fuel the next wave of settlement. In one of the fastest settlements in history, the population of Mississippi more than doubled from 1810 to 1820 and that of Alabama grew 16-fold, from barely over 9,000 to 144,000.

If your ancestors caught “Alabama fever,” look for them to have headed west and south during this mass exodus. Leaders in older states fretted over the depopulating effects of this “fever,” such as this 1817 lament from North Carolina Congressman James Graham: “The Alabama Leaver (sic) rages here with great violence and has carried off vast numbers of our Citizens.… There is no question that this feaver is contagious… for as soon as one neighbor visits another who has just returned from Alabama he immediately discovers the same symptoms which are exhibited by the one who has seen alluring Alabama.”

Finding Your Fickle Family

As you trace your Southern ancestors backwards across what once was the frontier of “the Old Southwest,” don’t look for them to have simply uprooted from, say, Virginia and then settled for good in Alabama. Migrating families typically tried several new homesteads, possibly in several states. Historian Owsley compares this fickle migration pattern to “a great drove of blackbirds lighting in a grain field” — one gust of wind and they’re aloft again, only to settle in the next field over.

You can look for patterns, however. Migrating families often went due west, and they looked for valleys to settle in that reminded them of the place they’d just left. They moved in clusters, with one family member or even a neighbor being the first to try a new area, and others in the cluster following later. Children of migrating families were more likely to eventually migrate again themselves. If you can’t trace your ancestors, try their siblings and other kin; look for unrelated people who lived near your ancestors and who may have lived near them in their previous home, too.

Census records can be valuable tools here, since federal censuses go back to 1810 for Louisiana, Kentucky and parts of Tennessee, 1820 for Mississippi and 1830 for Alabama and Arkansas. Some areas had territorial censuses even earlier. Texas, not a state until 1845, had its own census ranging from 1829 to 1836. You can access these through Family History Centers, the National Archives and larger libraries. Census records are also coming online at such subscription sites as <www.genealogylibrary.com> and <Ancestry.com > , as well as through volunteer efforts at <wvwv.usgenweb.org>.

Don’t just check for your Southern ancestors in one county or even one state, however. If you can’t find them in Alabama, for example, maybe they weren’t there long enough to be counted before heading for greener pastures in Mississippi or Texas.

The 1850 census was the first to list the names of all free inhabitants in a household as well as the first to record their birthplaces, so it gives a valuable snapshot of Southerners’ migrating ways — and may help you find patterns in your family’s past. That enumeration found almost 400,000 people born in Virginia, Georgia, Tennessee and the Carolinas who had landed in Alabama, Georgia (non-Georgia natives), Mississippi and Louisiana.

You can also explore records of what likely drew your ancestors to this part of the South in the first place — public land. More than 2 million title records for public land sales (called “patents”) are searchable online at the Bureau of Land Management’s site <www.glorecords.blm.gov>. These cover all the Southern states except the original colonies, Kentucky, Tennessee and Texas, from 1820 to 1908. It’s a great way to find not only your ancestors but their neighbors, whose names might help you take the next step backward.

What County Was That When?

A little history lesson is also helpful in finding your ancestors’ vital records, probate records and other state and local paperwork such as court cases and land transactions. Because of the shifting boundaries of the expanding frontier, your family may have switched from one county to another, or even changed states, without ever leaving home.

In 1750, remember, Virginia encompassed everything to the west of today’s state. Tennessee was largely claimed by North Carolina until 1784. Mississippi and Alabama were part of the Mississippi Territory from 1798 until statehood in 1817 and 1819, respectively, while Georgia claimed parts of Alabama and Florida until 1802.

More problematic for family historians is the shifting of county lines. In 1740, for example, all of non-coastal North Carolina was divided into just three counties; today, the state has 100 counties, and those in the western three-quarters have been subdivided several times. Orange County, for instance, was formed in 1752 from parts of Bladen, Granville and Johnston counties. And county lines weren’t just redrawn way back when: As recently as 1861, Mitchell County, N.C., was created from five “parent” counties.

Other counties simply changed names. In 1858, for example, Benton County, Ala., became Calhoun County, for John C. Calhoun.

The USGenWeb site’s state pages <www.usgenweb.org/statelinks-table.html> can help you unscramble your ancestors’ county lines and figure out what was which county when. The especially Byzantine evolution of South Carolina counties and “districts” is painstakingly traced on that state’s USGenWeb site at <www.geocities.com/Heartland/Hills/3837/sc_countyhistories.html>.

History also created special challenges for genealogy in Louisiana, where the counties are called “parishes.” That state’s diverse heritage means that you’ll find records in Spanish, French and even Latin.

Once you do place your ancestors, you might take advantage of “county heritage books.” Sharon Williamson, USGenWeb coordinator for North Carolina, says, “These books contain a combination of genealogy and history and make it much easier to get a picture of what early life was like in a particular place.” The county pages on USGenWeb state sites are a good place to check whether your ancestor’s county had such a book.

The Other Side of the South

Of course, not everyone in the South came from Europe, and hundreds of thousands “migrated” against their will. The first African slaves came to the South not long after the first settlers, in 1619. Though slavery took several decades to become widespread, by 1710 South Carolina had more blacks than whites and by 1800, the United States had almost 1 million slaves.

Tracing your slave ancestors in the South back past 1870, the year of the first post-Civil War census, typically requires identifying the slaveholding family and locating their records.

You’ll also want to consult an important new resource. In February, the records of more than 480,000 ex-slaves, extracted from the Reconstruction-era records of the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Co., were released on a searchable CD-ROM database. Depositors often named other relatives and their whereabouts, and early records included names of former slave owners and their plantations. You can search this CD-ROM free at any Family History Center or visit <www.familysearch.org>; click Order/Download Products, then Software Products.

American Indians lived throughout the South as well: among them, the Powhatan in Virginia; Tuscarora in North Carolina; Cherokee in the Carolinas and Georgia; Yamassee in South Carolina and Georgia; Creek in Alabama, Georgia and Florida; Choctaw in Missisippi; Seminoles in Florida; and Chickasaw in Mississippi and Alabama. White settlers, wars, treaties and mass relocations gradually drove most of them west to what became the Indian Territory, today’s Oklahoma.

A Gray Line in History

The Civil War marks a sharp boundary in the history and the genealogy of the South. Beginning with South Carolina’s secession in December 1860, your Southern ancestors lived in a different country for more than four years.

If you trace your family back to the 1860s South, Croom emphasizes the importance of studying the history of where they lived during and after the war before you try to push further backwards in time. Like other historic disruptions, the war may have prompted your ancestors to move.

You’ll find valuable information in Confederate military records and state pension files (unlike Union troops, who earned federal pensions, those on the losing side had to rely on their states). The best source for finding your ancestor’s regiment is the 16-volume Roster of Confederate Soldiers, 1861-1865 edited by Janet B. Hewett, available in major libraries. Once you find the right regiment, you may find firsthand reports of your ancestor’s unit in War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (known as the “OR” for “Official Records”) and its companion naval volumes. For pension records, you’ll need to consult individual state archives; Henry Putney Beers’ The Confederacy: A Guide to the Archives of the Confederate States of America is a good starting point. Also look for old issues of Confederate Veteran magazine, published from 1893 to 1932, and its two-volume index.

But not all Southern men served in the military. Some also sympathized with or joined the Union cause, and many families were divided by the war just as the nation was.

Gradually, painfully, in fits and starts, the post-Civil War South became more a part of the American mainstream. Researching your family in the South after 1865 is not so different from researching anywhere else in the US. Today’s “Dixie” is home to CNN and “America’s team,” Coca-Cola and NASA, Disney World and George W. Bush — hard to believe it was ever another, rebellious nation, much less an untamed frontier.

Little did Scarlett O’Hara dream what tomorrow would bring to the South when she opined, “Tomorrow is another day.” But we are that tomorrow, and frankly, it’s up to us to give a damn about how we got here.

A version of this article appeared in the August 2001 issue of Family Tree Magazine.