Whether you’ve been doing genealogy for a day or a decade, you’ve probably wondered how to handle some seemingly unanswerable ancestor question. Beating genealogical brick walls isn’t just a matter of how, though, but also of what. Trying to get by without the right resources will get you nowhere quickly – a lesson James M. Beidler, author of the syndicated newspaper column Roots and Branches, likens to a classic family history joke: A genealogist dies. Much to her chagrin, she learns she’s not going to heaven. But her spirits improve after the devil gives her the grand tour of hell – which, as it turns out, contains the biggest family history library anyone could imagine. What’s more, the genealogist gets her own desk, pedigree charts and countless records at her disposal. So she begins working in the library. A week later, the devil returns to ask how she’s doing. “It’s great,” she says, “except I can’t find a pencil or anything else to write with.” The devil replies with a chuckle, “Yes, that’s right. Hell, isn’t it?”

Clearly, lacking the proper tools can deliver you into eternal genealogical torment. So as you reconstruct your family tree, you’ll maximize your potential for success – and minimize frustration – by stocking up on some key roots research supplies and resources.

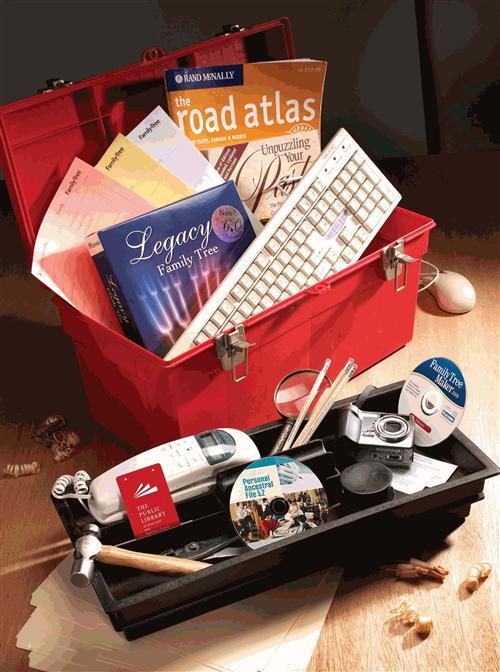

What tools will help you on your family history journey? We inventoried our own oft-used resources and polled our experts. Although every veteran researcher conducts his or her research a little differently – some rely on traditional pen-and-paper methods; others swear by high-tech strategies – most gurus agree these 21 items belong in every beginner’s family history toolkit (along with a subscription to Family Tree Magazine, of course!). So before you venture into the great genealogical beyond, consult this list and start stockpiling.

1. Blank charts and worksheets

Your ultimate objective is to fill in the blanks on your family tree, and to do that, you’ll need a supply of the charts and forms genealogists use to record information. Start with two staples: pedigree charts, where you document details about your ancestors (parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, etc.), and family group sheets, which summarize information about a nuclear family. This is the type of form where you record your siblings, aunts, uncles and cousins. You can download these and a variety of other forms – including census worksheets, cemetery transcription forms and research logs – for free from <www.familytreemagazine.com/freeforms>. Keep extra blank copies on hand to use as needed.

2. Research binder

Whether you’re poring over documents at home or cranking microfilm at the library, you’ll want to have key family facts and research helps at the ready. Compile a three-ring binder that contains copies of your filled-in pedigree charts and family group sheets (or printouts from a genealogy software program – see item 5). Add alphabetical lists of the surnames and localities you’re researching, timelines showing where ancestors were when, and a selection of maps (see No. 11). It also helps to have a log of the sources you’ve checked, so you won’t waste time looking up the same record again and again.

Maureen A. Taylor, author of Uncovering Your Ancestry Through Family Photographs, revised edition (Family Tree Books), suggests including ancestral photos in your binder, too: Copy several onto a single sheet to reduce bulk – and avoid damaging the originals – then place the page next to your materials on that ancestor or family. Details in the pictures could help you confirm clues in a document; for example, the place of residence on a census schedule might match the location in a photographer’s imprint. Pictures also can provide encouragement. “When you get frustrated,” says Taylor, “stare at the pictures of the troublesome ancestors and hope they inspire you to look in another direction.”

3. Storage

4. Computer access

The computer probably is the best thing to, happen to genealogy since the invention of the pedigree chart. Although you still can do your sleuthing the old-fashioned way, a computer will revolutionize your roots research: It’ll enable you to easily swap data with fellow researchers, and access people, information and records long-distance. Computer genealogy doesn’t necessarily require you to buy a system, either – you can use the machines at your local library or Family History Center. (Run by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, these free research facilities are branches of the Family History Library in Salt Lake City. Find one near you by entering your ZIP code in the box at <www.familysearch.org>.)

If you plan to use a publicly accessible computer, though, don’t forget to budget for the cost of printouts (which add up quickly). And consider investing in storage media – for example, a flash drive or recordable CDs – that are compatible with the machine you’re using, so you can quickly call up a file or search results on your next visit. After all, the facility probably won’t let you save your personal research files on its computers’ hard drives. Check with the staff about computer policies and compatibility.

5. Software

Want a tool that creates fully filled-in pedigree charts and research reports for you? One that organizes all your ancestral information so you can call it up in an instant? Then you need genealogy software. You can choose from an array of programs that process and store all your pedigree data. Basically, you enter all the facts you’ve collected about your kin, and the software saves them in a database. You can attach photos and even link facts to images of the documents where you found the information. Best of all, if you ever switch or upgrade your program, you don’t have to retype everything – all genealogy software lets you save your database as a GEDCOM, a file format that’s compatible with other family tree programs. To sort out your options, consult our roundup of popular programs in the May 2005 Trace Your Family History, a special issue of Family Tree Magazine.

6. Internet access and an e-mail account

As far as we’re concerned, the Internet ranks a close second to computers as an essential electronic family history tool. (In fact, we’d give it top billing if not for the fact that you need a computer to access the Web.) In the past, you could get your hands on key sources such as censuses, vital-records indexes and military records only at libraries and archives. Now you can connect to many of these records with just a few clicks – especially convenient if the repository that holds these desirable documents is halfway across the country. Besides finding actual ancestral facts and records online, you can save time in your offline research by doing legwork on the Web. For example, before you venture to the library, check its catalog online to be sure it has the materials you’re looking for.

If you don’t own a computer, most public libraries have terminals with Internet access, as do Family History Centers. Whether you log on from home or the library, we advocate getting an e-mail account just for genealogy – sign up for a free Web-based service such as Yahoo! Mail <mail.yahoo.com> or Gmail <gmail.google.com>. The separate account will keep your research-related messages from encroaching on the rest of your correspondence, and the Web-based service allows for an e-mail address that never changes. That way, if someone comes along three years from now with the answer to a query you left on a message board yesterday, you won’t miss the message because it got sent to an obsolete e-mail account.

Now for the catch: Though we encourage you to embrace the Web’s timesaving potential, don’t make it your only source. You can’t simply visit a few Web sites and download your entire family tree. Courthouses and archives still hold oodles of records that haven’t hit the Net. And online information isn’t always accurate. Transcribers make mistakes, and visitor-supplied information often lacks sources. So use the Web as a complement to traditional genealogy methods. Which leads us to our next essential resource…

7. Library card

Genealogists still have ample opportunity to wear out their library cards. If your own library doesn’t have a book or roll of microfilm you’d like to use, you may be able to get that resource through interlibrary loan. Libraries also subscribe to various research databases cardholders can use. In some cases, you may be able to search the databases at home by logging on to the library’s Web site and entering your library card number. For instance, thousands of public libraries across the country offer remote access to census records and digitized books through HeritageQuest Online <www.heritagequestonline.com>; contact your local or state library to see if it’s one of them.

8. Research tote bag

Speaking of libraries, prepare yourself for your next venture into the stacks (or courthouse or archives) by getting a sturdy tote bag and stocking it with everything you’ll need at the research facility. Some must-have contents: mechanical pencils (no sharpening needed), notebook paper and/or index cards, blank forms, paper clips and lots of change for the photocopiers. With your tote bag already packed, you’ll cut down on your pre-trip planning time, and won’t have to worry about winding up like our unfortunate hell-bound family historian.

9. Basic genealogy how-to book

If you’ve ever tried to program a new DVD player or mobile phone before reading the directions, you’ll understand the futility of starting your family history search without instruction. You need a genealogy “user manual,” such as Croom’s classic Unpuzzling Your Past (Betterway Books). This particular book mixes details about basic genealogical sources with guidance on using them in your research. Other beginner books tilt more heavily toward how-to or focus primarily on records – browse your bookstore’s genealogy section to find one that’s suited to your learning style. You’ll refer to it often. (That’s right: Even the most experienced genealogists can’t intuitively locate ancestors the way your 8-year-old grandson masters electronic devices within 10 seconds.)

10. State-by-state records reference

As you embark on your quest for genealogical records, questions will arise: What happened to the Thompkinsville, Ky., probate records? From what parent county did Somerset County, NJ, spin off? Where do I write for Washington County, Ore., marriage certificates? If you keep a reference such as The Family Tree Resource Book for Genealogists (Family Tree Books) on your shelf, you can look up the answers lickety split. The Resource Book has contact information, record details and historical background for every US county. Other similar volumes are the Red Book (Ancestry) and The Handybook for Genealogists (Everton Publishers).

11. Atlas

Maps help you pinpoint your forebears’ hometowns, migrations and surroundings. A collection of present-day US maps – such as a road atlas – is invaluable for looking up locations and planning research outings. “Be sure to get one that shows county names and boundaries,” suggests Rick Crume, author of Plugging Into Your Past (Family Tree Books). “In addition to a regular atlas, I really like the Township Atlas of the United States, which has county maps showing town and township boundaries.” (It’s out of print, but many libraries have copies.) You also should get an atlas or detailed maps of any state or country you’re researching. Specialized atlases may come in handy, too: For example, you can find out how county boundaries changed over time with Map Guide to the US Federal Censuses, 1790-1920 by William Thorndale and William Dollarhide (Genealogical Publishing Co.).

12. Relationship chart

After posting queries on online message boards and in genealogy society newsletters, you connect with another researcher who’s tracing your great-great-grandpa Hiram Humdinger’s line. You know you’re related – but how? Let a relationship chart come to your rescue. It’ll help you calculate the “degree of cousin-hood” between any two people who share an ancestor. You’ll find a sample relationship chart – with step-by-step instructions – at <www.familytreemagazine.com/freeforms>; Unpuzzling Your Past contains one, too.

Here’s a handy tip for genealogy software users: Many popular family tree programs come with built-in relationship calculators, so you can pick any two people, select the calculator option and instantly learn how they’re kin. You’ll find a similar tool online at <www.iroots.net/tools/cusncalc>.

13. Business cards

Longtime genealogists can tell you countless tales of how networking pays off: A note left at an ancestral grave prompts a visiting relative to get in touch. A letter to the editor of a smalltown newspaper elicits a response from a reader who once knew your family. You can make it easier for such help to find you by creating business cards especially for genealogy. Include your name, contact information and a list of the surnames you’re researching. Keep some cards in your research tote bag, and when you go to a cemetery, research facility or workshop, leave your card. You never know who might contact you – or what juicy genealogical details they could provide.

14. Telephone

Of course, if you’re going to give out your contact information, you need a way for people to get a hold of you in the first place. And while you often can get information by zipping off e-mail messages and penning old-fashioned letters, sometimes it’s faster and more effective to just pick up the phone and push buttons. “I couldn’t do genealogy without a telephone, especially since not everyone has e-mail, not everyone answers e-mail questions, and not all Web sites answer a genealogist’s questions,” says Croom. “I call libraries with reference questions, call relatives to share info and ask questions, [and] call libraries and courthouses for fees and hours.”

15. Tape recorder or video camera

If you already have a camcorder for filming the kids’ or grandkids’ dance recitals and soccer games, this is another application for it. For camera-shy subjects – or if a camcorder’s not in your budget – go for a digital voice recorder. You can get one for around $40.

16. Scanner and/or digital camera

These electronic devices have gotten more popular with family history buffs as they’ve become more affordable (you now can get a genealogically adequate scanner for under $80 and a camera for less than $150). They’re well worth the investment. With either gadget, you can create digital copies of old photos and documents. Not only will those electronic versions serve as backups in case of disaster, you also can share them with relatives via e-mail, on CDs or online – far more economical than copying and mailing paper.

Most scanners come bundled with image-editing software you can use to retouch faded or damaged pictures (see the April 2004 Family Tree Magazine for tips). And a digital camera could prove invaluable during your research outings: Since handling old records hastens their deterioration, archives don’t always allow visitors to make photocopies – but some will let you photograph those documents. Remember to pack extra batteries, advises Taylor, along with a high-capacity memory card and a tabletop tripod or clamp to steady the camera.

17. Magnifying glass

If you haven’t yet attempted to decipher a census enumerator’s chicken scratches or a European parish priest’s scrawls, you’ll soon see that poor eyesight isn’t the primary reason family historians usually carry magnifying glasses. Get a standard magnifier – available from office-supply and drug stores – to enlarge hard-to-read handwriting and inspect the details in photographs. If you’re willing to splurge, look into the Magnabrite <www.magnabrite.com>, which works like an artist’s or photographer’s loupe and comes in four sizes (ranging in price from $18.95 to $174.95). We also recommend purchasing a mini magnifier to keep in your research tote bag.

18. Cemetery kit

Genealogists spend a lot of time in cemeteries, so you might as well round up your gear. You’ll need paper and pencils for copying tombstone inscriptions, as well as a spray bottle (water enhances writing on stones) and a camera to document your discoveries. Sharon DeBartolo Carmack, author of Your Guide to Cemetery Research (Betterway Books), suggests you also pack a carpenter’s apron, gardener’s knee pads, garden shears, a whisk broom, sunscreen, moist towelettes and insect repellent. Don’t forget tombstone-rubbing tools such as butcher paper or interfacing fabric, masking tape, and jumbo crayons or rubbing wax. But leave the shaving cream and chalk at home: Preservationists advise against using any acidic substance on a grave marker, as it could speed deterioration. For cemetery research tips, read Carmack’s article in the June 2005 Family Tree Magazine.

19. Archival supplies

You need a way to store family memorabilia for posterity. The bad news: Your shoebox system doesn’t meet archival standards. The good news: You can buy safe storage items from various archival suppliers, including Hollinger Corp. (800-634-0491, <www.hollingercorp.com>) and University Products (800-628-1912, <www.universityproducts.com>). Get boxes for papers and clothing (such as Grandpa’s Army uniform); envelopes for photos and small ephemera; and plastic sleeves for negatives.

20. Society memberships

Don’t let the idea of joining a genealogical society intimidate you – these groups will welcome you into the fold, and you’ll welcome the research benefits that come with membership. In addition to meetings, societies offer publications, library resources, seminars and even online databases.

Genealogy groups also typically have volunteers who can give you the scoop on local resources and help with your research conundrums. If you join a society in your out-of-state ancestors’ locale, some kindhearted souls might even look up records for you. Start by signing on with a local organization – it’s not much of a financial commitment (annual dues usually run $25 or less), and you’ll build a network of genealogy buddies.

21 Genealogy course

Equipment Sale

In a perfect world, we’d all have unlimited funds to pursue our pedigrees, but that’s rarely the reality. So what if you can’t afford to buy all these supplies? Can you still do genealogy?

Of course you can – just rely on the same resourcefulness you use to trace your family tree. A few tips to reduce the drain on your pocketbook:

• Take advantage of your local library and Family History Center, which offer many of the items mentioned here, including books, atlases, classes and computer access.

• Inquire about acquaintances’ old electronic equipment. Has a friend or relative upgraded her computer? Ask what she did with the old one. She might give you a bargain – or just give you the system.

• Pool your resources with a genealogy buddy. You can increase your purchasing power by splitting the cost of office supplies.

• Look for freebies. We let you in on where to find gratis genealogy software, charts and other goodies in the June 2006 Family Tree Magazine.

Skilled Worker

In addition to physical gear, every family historian needs these intangible “tools”:

• Inquisitiveness: Genealogists are like detectives. Curiosity will motivate you to solve the mystery of your past.

• Patience: Don’t expect to search a handful of Web sites, hit a couple of libraries and walk away with a complete family tree. “Genealogy is a lifetime pursuit that is never ‘finished,’” says Croom. “It takes time to research, to hear from queries, to receive materials from archives, and to learn about each place where ancestors lived and how to research ancestors from there.”

• Politeness: You’ve heard the expression, “You’ll catch more flies with honey than with vinegar.” Keep that in mind when you visit courthouses, libraries and archives. Don’t waylay busy staffers with a long-winded account of your ancestry. Be courteous, be brief, and you’ll be rewarded.

• Attention to detail: Sometimes a seemingly insignificant clue is the key to solving a family tree puzzle – for instance, the props in a picture might tell you when it was taken. Your success rests on sweating the small stuff.

• Problem-solving ability: In genealogy, as you know, answers don’t always stare you in the face. When you uncover conflicting information or find that the record trail has petered out, you’ll have to think critically, challenge your assumptions and get creative.

From the September 2007 issue of Family Tree Magazine.