Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

New York state and its municipal namesake, America’s “city that doesn’t sleep,” were the first stops for millions of immigrants in the 1800s and 1900s—but the Empire State has a full four centuries of settlement history for you to investigate. Your New York ancestors saw distinct stages of state history: early days under Dutch rule, an English Colonial era dominated by large landowners, a time as a pathway for people leaving New England, and finally, a period as home to the nation’s busiest port of entry. Each era created a vast empire of genealogical records we’ll help you conquer.

Dutch (and English) treat

In 1609, explorer Henry Hudson roamed the river that bears his name (it was first called the North River; the Delaware was the South River) and claimed the area for the Dutch. Settlement began in earnest in the 1620s, as New Netherland residents jockeyed for land and colonial power with the New Englanders on Long Island. The English seized the colony in 1664 and renamed it for the Duke of York.

Most 18th-century New Yorkers were from New England, but several thousand Germans—the first German mass immigration—arrived in 1710. A small but vibrant cluster of Huguenots came in the late 1600s, and Scots-Irish filtered into the Lower Hudson Valley.

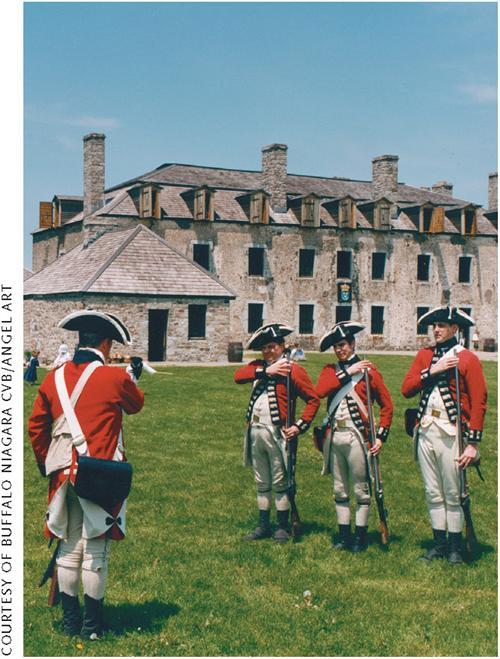

Governors granted vast tracts (called manors) in upstate New York to landholders such as Robert Livingston, who secured a patent in 1686 for 160,000 acres. The large estates, along with pressures from American Indian tribes, inhibited settlement until after the Revolutionary War.

Colonial border disputes, primarily with New England states, ended when Massachusetts got two of New York’s original 12 counties. The Empire State claimed land in what’s now Vermont until that area became a state in 1791. Today, New York counties are divided into towns (the equivalent of townships in most other states), which include cities, incorporated villages and hamlets. New York City didn’t reach its current extent until 1898; each of its five boroughs (Brooklyn, Bronx, Manhattan, Queens and Staten Island) is its own county.

Welcome sign

New York boomed after the Revolution as settlers from other Colonies and Europe pushed upstate. In 1825, the Erie Canal connected the Hudson River with Lake Erie, cementing the Empire State’s role in western expansion by making the Midwest more accessible.

New York City established itself as the nation’s top port for commerce and immigration during the second quarter of the 1800s. Germans and Irish were the first to come in large numbers; Southern and Eastern Europeans began arriving after mid-century. Many of these immigrants settled right in New York City, swelling it into a megalopolis—and making ship manifests an important New York record group. You may immediately think of the Ellis Island immigrant processing center in New York Harbor, but Castle Garden (now Castle Clinton National Monument) in Manhattan’s Battery Park predates that depot. Immigrants arrived there as early as 1820; it became an official immigration station in 1855.

Search for passengers to Castle Garden (through 1890) and Ellis Island (1892 to 1924) free online. Having trouble finding an ancestor? Try using Stephen P. Morse’s flexible One-Step search tools. For Ellis Island, the Gold form offers sophisticated searching and the Blue form is geared to Jewish surnames.

Immigrants also used ports on the Great Lakes and the Canadian border. Look for records of these entries in Ancestry.com‘s US Records Collection (which you’ll need a subscription to access, or you can access it for free through libraries offering Ancestry Library Edition) and on microfilm at National Archives and Record Administration (NARA) facilities, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ Family History Library (FHL) and large public libraries.

With so many immigrants arriving in New York—8 million-plus in the Castle Garden era and more than 16 million through Ellis Island—you’ll find naturalization records by the bucketful, too. For the earliest ones, consult the Works Progress Administration’s 1792-to-1906 card index for New York City boroughs. It’s available from that city’s NARA Northeast Region. The FHL has this and other naturalization indexes on microfilm.

County clerks have naturalizations made in county courts. The New York section in Ancestry’s Red Book, third edition, edited by Alice Eichholz, gives a good rundown of published abstracts and guides. Search New York City naturalizations using Steve Morse’s One-Step tool (find it under Birth, Death and Other Vital Records).

Vital domain

When it comes to New York state birth, marriage and death records, exceptions are the rule. You’ll find a few Colonial listings in town records, mostly in areas New Englanders settled, such as Long Island and east of the Hudson. Marriage licenses and bonds are indexed in New York Marriages Previous to 1784 (Genealogical Publishing Co.).

Continuous vital record-keeping dates only from 1880. Under a new statute, town clerks retained duplicate certificates and forwarded originals to the state capital in Albany. It’s worth checking with local registrars (for births and deaths), town clerks (for marriages) and historical societies: Cities including Albany, Buffalo, Rochester, Syracuse, Utica, Yonkers and New York kept records earlier than 1880, and some cities didn’t send originals to Albany until the early 1900s.

Genealogists can contact the state department of health for uncertified copies of birth certificates older than 75 years, and marriage and death certificates older than 50 years (restrictions may be waived for descendants of the person whose record it is).

New York City’s vital records are even more complicated, and the state office doesn’t have them (except from areas the Bronx and Brooklyn annexed in the late 1800s). The city’s municipal archives has the low-down on when records begin for what areas. Steve Morse also has search tools for New York City marriages, primarily covering the 1890s to the 1930s.

Records empire

The state’s roster of other records could stretch as long as the New York Thruway. But these key source groups will drive your research:

• Military: The state archives (see resources) has various military records through the 20th century. Its Web site offers a guide to them (click Research Room, then Military), as well as a database of New York’s Civil War soldiers. Submit a War Service Records Request to have archives staff search its records.

Colonial militia lists appear in New York Colonial Muster Rolls, 1664-1775 (Genealogical Publishing Co.), an index that’s also on Ancestry.com. Use NARA’s Order Online site to request service records and pension files for federal soldiers in the Revolutionary War, War of 1812 and Civil War.

• Land and court: The county clerk is your go-to person for civil and criminal court cases, deeds and mortgages. Since the 1780s, county surrogate’s courts have handled estates. Colonial wills are scattered in county courts, the state archives, New York Genealogical & Biographical Society (NYG&B)—even in Boston, from New York’s brief time in the Dominion of New England. Look for them on FHL microfilm and seek published abstracts such as Calendar of Wills by Berthold Fernow (Genealogical Publishing Co.), which covers wills recorded with the county clerk in Albany and other courts from 1626 to 1836.

The state archives has records of land sales from the government. If your ancestor was one of the many New Yorkers who rented from large landholders, see Landlord and Tenant in Colonial New York by Sung Bok Kim (University of North Carolina Press). Also use the National Union Catalog of Manuscript Collections to search university and other repositories for papers of manor-owning families.

• Censuses: Find New York’s federal censuses through 1930 (except the destroyed 1890 count) at NARA and its regional research facilities, the FHL and Family History Centers, large public libraries, Ancestry.com and Heritage-Quest Online (free via subscribing libraries).

The state also took censuses periodically; surviving counts for some counties span 1825 to 1925. Beginning in 1825, they include citizenship details about immigrants; the 1855 and later tallies name all members of each household. Microfilmed censuses are at the FHL, state library and NYG&B; Ancestry.com has some indexes. So no matter which era brought your ancestors to New York, you’ll find records aplenty to start your genealogical empire.