The most important thing to know before starting your North Dakota family research is that two states have “Dakota” in their name. Folks in the upper Great Plains hate it when newscasters refer to “the Dakotas,” as if it’s one big state — perhaps because this area spent many prestatehood years being fobbed off from one territory to another. (But it’s true that North Dakota legislators recently toyed with renaming the state simply “Dakota,” forever consigning their southern neighbor to add-on status.)

When North Dakota first became part of the United States, it was part of one big chunk of land — the 1803 Louisiana Purchase from France, which included the southwestern half of today’s state. French explorer Pierre Gaultier de Varennes et de La Vérendrye, the first white man to reach North Dakota, arrived in 1738. Permanent white settlement didn’t start until 1812, when Scottish pioneers from Canada settled in Pembina. Six years later, the United States acquired that part of northeastern North Dakota; all of North Dakota then became part of the Missouri Territory.

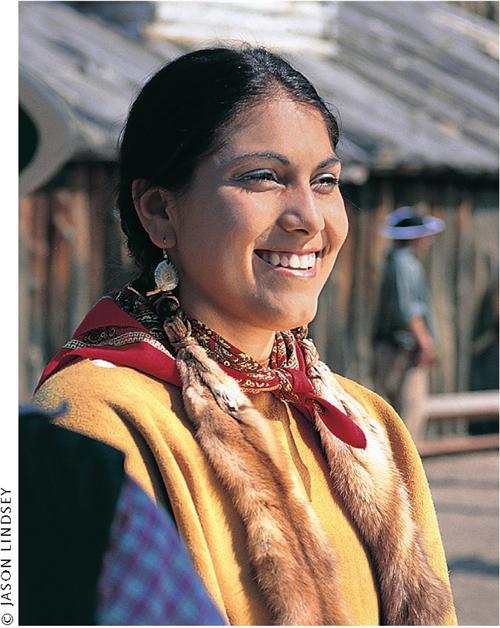

American Indians had lived there for more than 11,000 years, of course. La Vérendrye encountered Mandan villages along the Missouri River, as did Lewis and Clark during their 1804-to-1806 journey. The Sioux and Chippewa later conflicted with settlers before being confined to reservations. If your North Dakota ancestors include American Indians, the Family History Library (FHL) <www.familysearch.org> has microfilmed Bureau of Indian Affairs records spanning 1872 to 1952. Originals are at the National Archives and Records Administration’s (NARA) <archives.gov> Central Plains regional facility in Kansas City, Mo.

From 1834 until the creation of Dakota Territory in 1861, various pieces of what’s now North Dakota were in the territories of Michigan, Wisconsin, Iowa, Minnesota and Nebraska. North Dakota was included in the 1836 Wisconsin, 1840 Iowa and 1850 Minnesota territorial censuses. Dakota Territory censuses took place in 1860, 1870, 1880 and 1885; indexes are available via the FHL, along with mortality schedules for 1870, 1880 and 1885. You can search many of these censuses on the subscription site Ancestry.com <Ancestry.com > and on HeritageQuest Online <heritagequestonline.com> (available through subscribing libraries). Thanks to North Dakota State University’s Institute for Regional Studies and University Archives, the 1885 census — 151,500 names from the northern part of the territory — is free at <www.lib.ndsu.nodak.edu/ndirs/databases/census.php>.

Dakota Territory land went up for grabs in 1863 under the Homestead Act, but Indian attacks and the Civil War delayed settlement. In 1871, the railroad from Minnesota reached the Red River, sparking a “Dakota boom”: From 1878 to 1886, 100,000 immigrants arrived. Some founded “Bonanza farms” of up to 65,000 acres in the Red River Valley. Those who went farther west launched a cattle industry that thrived until the winter of 1886-1887 wiped out three-quarters of the herds.

Appropriately, North Dakota’s first homesteader, N.E. Nelson, was Norwegian — the hordes who followed him made North Dakota the nation’s most Norwegian state. More than a third of its population claims ancestry from Norway. Others came from Germany, Russia, England, Ireland, Sweden, Canada and older Midwestern states.

Look for North Dakota immigrants in the state historical society’s Naturalization Records Database <www.lib.ndsu.nodak.edu/ndirs/databases/naturalrec.php>. With more than 212,000 names, it’s complete for all the state’s counties. The society also has original naturalization records; many are available on FHL microfilm, too.

Peaceing together the past

The US government split the northern and southern parts of Dakota Territory in 1889, when both were admitted to the Union as states. Because the 1890 census was largely destroyed, the first extant census for North Dakota is the 1900 tally. The 1890 Union veterans schedule did survive, and is available at the FHL and on Ancestry.com.

When you’re searching census records, cautions Char Kibbie, assistant state coordinator of the North Dakota GenWeb Project <rootsweb.com/~ndgenweb>, “remember that young men often hired out in the spring, when census takers made their rounds, to work other farms, and young women helped out at neighboring farms as well. If you don’t find who you’re looking for, search the whole township and even neighboring ones. Sometimes an individual could appear in two different families as a hired hand on the same census. It could take [enumerators] days to canvas an area.”

Birth and death records began in 1893, although gaps exist. Counties kept some early marriage records, but statewide recording didn’t start until 1925. You can order copies of vital records from the Department of Health <ndhealth.gov/vital> for $7 (birth) or $5 (death and marriage). Search a database of death certificates from 1881 to 2004 at <secure.apps.state.nd.us/doh/certificates/deathCertSearch.htm>. Probate records are archived in county courthouses, but the FHL hasn’t yet microfilmed them.

North Dakota was a public-land state, so records of its land boom are at the Bureau of Land Management’s office in Billings, Mont., and at NARA. The state historical society also keeps local land-office records, and township plats are at the state water commission (701-328-2750, swc@nd.gov). You can search Peace Garden State land patents online at <www.glorecords.blm.gov>.

During a second “Dakota boom” between 1898 and 1915, more than 250,000 newcomers flocked to the state. This wave of immigrants worked smaller farms and ranches and helped fuel the growth of cities such as Bismarck, Fargo and Grand Forks. Bismarck gave birth to what’s now North Dakota’s oldest newspaper, the Tribune, back in 1873. The Fargo Express followed the next year. The state historical society maintains a large collection of historical papers, most of which you can borrow on microfilm through interlibrary loan. The Tribune is part of Ancestry.com’s Historical Newspaper Collection. (Ancestry.com also has 1889 and 1891 Grand Forks city directories.)

Researching accordingly

North Dakota researchers can tap a wealth of other records. The North Dakota Biography Index (NDBI) began as Fargo resident Allen Peters-en’s card file; in 2000, the Institute for Regional Studies expanded it and launched it as a searchable online database <www.lib.ndsu.nodak.edu/ndirs/databases/bio.php>. The NDBI now includes biographies of more than 211,000 North Dakotans from some 741 sources, including county, community, church and business histories, as well as WPA files. Once you’ve found an ancestor’s biographical sketch, you can get a complete copy for just $5.

The Sioux Valley (South Dakota) Genealogical Society’s index of people who lived in Dakota Territory at the time of statehood <rootsweb.com/~sdsvgs/index1.htm> is worth checking out, too. These early arrivals have been honored with pioneer certificates; the index gives each person’s birth and death dates, birthplace and pioneer certificate number, which you can use to obtain further information.

The North Dakota historical society’s Oral History Project <www.state.nd.us/hist/sal/gen/infoh.htm> has captured the lives of early North Dakotans. The collection includes more than 1,200 interviews and 3,500 photographs; it’s indexed by individuals’ names. You can order copies of records for a fee.

Local history books are another fruitful source. For a bibliography of local histories, consult the Reference Guide to North Dakota History and North Dakota Literature (see resources), which is available through interlibrary loan.

The State Archives and Historical Research Library <www.state.nd.us/hist>, located in Bismarck, is a division of the state historical society. Its collections are available to researchers in the Orin G. Libby Memorial Reading Room of the North Dakota Heritage Center, or you can request a search by mail. Limit requests to three per letter and provide as much information as possible, including names, precise locations and dates.

Still stumped? “The local courthouses are usually the best places to do research,” says North Dakota GenWeb Project state coordinator Michelle Savre, “but North Dakota State University has a wonderful Biography and Genealogy Department with many resources.” (You can learn more at <www.lib.ndsu.nodak.edu/ndirs/bio”genealogy>.) She suggests the Red River Valley Genealogical Society <www.redrivergenealogy.com> for researchers in eastern North Dakota.

“Contacting local historical societies has been a boon to my research,” adds Kibbie, who’s gotten plenty of assistance with Dickey County ancestors from that area’s historical society. Likely your requests will be received just as warmly. That’s Dakotans — er, North Dakotans for you.

From the February 2007 issue of Family Tree Magazine.