Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Oct. 7, 1763, King George III of England issued a proclamation forbidding colonists from settling beyond the crest of the Appalachian Mountains and encroaching on Indian territory. But that didn’t stop early Virginians, Pennsylvanians and North Carolinians lured by rumors of Tennessee’s lush farmland and the prospects of independence and economic stability. By spring of 1772, they had established permanent settlements along East Tennessee’s Watauga River, and created America’s first independent government, the Watauga Association.

Tennesseans have always embodied a pioneering spirit. After achieving statehood in 1796, many went on to explore lands farther west, including Missouri, Arkansas, Texas and Oklahoma. Those who stayed helped grow the state’s economy and its largest cities — Memphis, Nashville, Knoxville and Chattanooga.

Three US presidents have come out of Tennessee: Andrew Jackson, James K. Polk and Andrew Johnson. And of course, so have dozens of country crooners and Memphis blues musicians.

Are you ready to discover the pioneers in your family? Let us lead the way.

The wild frontier

Tennessee has three distinct regions: East Tennessee, characterized by its mountainous terrain; Middle Tennessee, known for its fertile farmland; and West Tennessee — the state’s final frontier — which developed close ties to the Deep South and an economy based on cotton and the Mississippi River.

When the first white settlers arrived in upper East Tennessee, the Cherokee Indians already had driven most other tribes out of the region. The Cherokee taught the pioneers — primarily Scots Irish and some Germans, English, French Huguenots, Swiss, Welsh and African slaves — to hunt, build log cabins and utilize various plants. But as the settlers appeared more land-hungry, the Cherokee saw them as a threat. So began a long period of conflict, which lasted until the late 1830s and ended with the forced removal of the remaining Cherokee along the Trail of Tears.

Though the Appalachian Mountains offered an abundance of foods, medicines, dyes and timber, living in the wilderness among hostile Indians proved difficult for settlers. Still, they pushed westward into the Central Basin of Middle Tennessee and eventually all the way to the Mississippi River.

Border shifts

In 1777, North Carolina annexed the Watauga Association, renamed the Washington District after the American Revolution broke out. The state transferred the land to two existing counties (Rowan then Burke), finally dubbing it the independent Washington County. Still seeking self-government, the Wataugans appealed to Congress for independence, but were denied it without North Carolina’s approval. In 1789, North Carolina ceded Washington County to the US government, and the area became known as the Territory of the United States South of the River Ohio (or simply the Southwest Territory).

By 1795, the territory had 77,000 residents — enough to achieve statehood. Tennessee’s population continued to rise, and county borders constantly shifted. When residents felt they lived too far from the county seat to conduct legal business, they petitioned for the creation of a new county.

Early Tennesseans left the usual county records, including petitions, deeds, wills and licenses, but finding them can be a challenge. Even an ancestor who stayed put may have lived in multiple counties. If that’s the case, his records could be scattered in various county courthouses. For maps of boundary changes, go to Tennessee GenWeb <www.tngenweb.org>, click on TNGenWeb Map Project, then Tennessee County Formation Maps.

Starting places

You’ll need to identify your ancestors’ county (or counties) because most genealogical records are based there. If you don’t know this information offhand — and your relatives don’t, either — you can find it a few different places:

• Census records: Tennessee didn’t take state or territorial censuses. The federal government first enumerated Tennessee in 1810, but only the Rutherford County census survived. Likewise, most 1820 records no longer exist, except for Tennessee’s eastern counties. You can access Tennessee enumerations from 1830 to 1930 (except 1890, which burned) at large libraries, National Archives facilities <www.archives.gov>, the Salt Lake City-based Family History Library (FHL) <www.familysearch.org> and its branch Family History Centers (FHCs), as well as through subscriptions to Ancestry.com <Ancestry.com > and Genealogy.com <www.genealogy.com>.

• Tax lists: If your ancestors resided in Tennessee prior to 1830, look to tax records as alternatives to the census. Some lists provide just the names of taxpayers, but others include the amounts of property, their value and locations.

Both the Tennessee State Library and Archives (TSLA) <www.state.tn.us/sos/ statelib> and the FHL have microfilmed tax lists. TSLA will make copies of lists that have been published in book form for $5 per surname. Consult the Index to Early Tennessee Tax Lists by Byron and Barbara Sistler, which contains about 46,000 entries representing 1787 to 1827, and Early East Tennessee Taxpayers by Pollyanna Creekmore, covering 1778 to 1832. Both are available at the FHL, TSLA and other libraries.

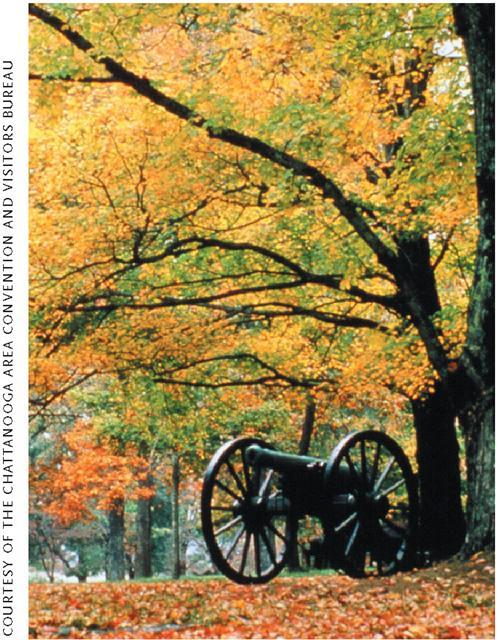

• Military records: Shortly after gaining statehood, Tennessee contributed soldiers to the War of 1812 (which earned it the Volunteer State nickname), 1818 Seminole War, 1836 Cherokee Removal and Mexican War (1846 to 1848). The Revolutionary War occurred before Tennessee became a state, so few people from that area actually fought in it. Tennesseans fought on both sides of the Civil War. When their state joined the Confederacy in 1861, a number of East Tennesseans left home to fight for the Union.

TSLA has numerous military records, including indexes of soldiers in various conflicts. You can search databases of Confederate pension applications and a partial index of WWI veterans online (from the TSLA home page, click on Tennessee History and Genealogy, then on Military Records).

The FHL also has a broad selection of microfilmed military records and indexes, which you can borrow through your local FHC. To search the FHL’s online catalog, click on Library, then on Family History Library Catalog, and run a place search on Tennessee.

Vital tips

Statewide registration of births and deaths began in 1908, but not until 1914 did death records contain parents’ names and other genealogically useful details. TSLA holds these early records, and you can search a complete index of 1908 to 1912 death records on its Web site. TSLA also has a partial index covering 1914 to 1925.

Tennessee birth records are closed for 75 years, and death records for 50. To get copies of birth records from 1914 on, write the Office of Vital Records. TSLA has death records from 1914 to 1953. You can request a lookup by mail. Death records from 1954 to the present are at the Office of Vital Records.

If your ancestors lived in Memphis, try searching the Memphis/Shelby County Public Library and Information Center’s Memphis/Shelby County Death Index (1848 to 1901) and Miscellaneous Deaths Index (1881 to 1882, 1902 to 1914, and 1941 to 1944). The Yellow Fever Deaths Index covers the 10,000 Memphians who died during an 1878 epidemic. Find these lists at <history.memphislibrary.org>.

Since 1945, the Office of Vital Records has recorded statewide marriages. Contact that office for records from the past 50 years; TSLA has a statewide index covering 1945 to 1953. Earlier marriage records reside in county courthouses. The FHL has microfilmed indexes of pre-1861 marriages, which you can borrow for viewing at FHCs.

Super sources

Tennessee researchers have plenty of resources at their fingertips. Here are a few more to check out:

• The Draper Manuscript Collection, nearly 500 volumes of manuscripts, papers and books about the history of the trans-Allegheny West, includes records of Tennessee. The State Historical Society of Wisconsin holds the original documents, but you can view the collection on microfilm at TSLA, the FHL and other libraries.

• Suspect your ancestors were among Tennessee’s first white settlers? Consult First Families of Tennessee: A Register of Early Settlers and Their Present-Day Descendants compiled by the East Tennessee Historical Society.

• Of course, there’s also a chance your forebears were some of Tennessee’s native sons and daughters. See the April 2004 Family Tree Magazine for a guide to researching American Indian ancestors. If you have Cherokee forebears, see the First People of Tennessee and the American Southwest portion of Tennessee GenWeb <www.tngenweb.org/ tnfirst>.

For more tools, consult the FHL’s Tennessee Research Outline; click Research Helps, then the letter T.