Whether your Canadian ancestors were First Nations peoples, early French settlers, Loyalists seeking refuge after the American Revolutionary War, or more-recent immigrants from Ukraine or elsewhere, records probably exist to tell their stories.

And many of those records are now online. Church records of baptisms, marriages and burials in Quebec go back to the early fur traders. Muster rolls and land petitions document the Loyalist experience. Census and vital records reveal key facts about 19th- and 20th-century Canadians. And large collections of newspapers, journals and books give us a glimpse into the daily lives of all of them.

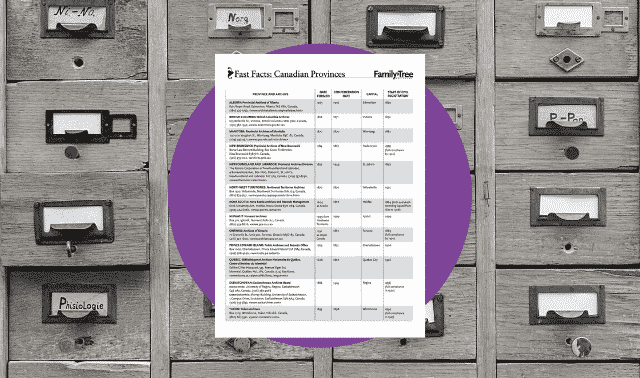

The following list includes 14 of the best websites for researching your Canadian ancestry, separated into five categories. Websites that require a paid subscription are indicated with $.

Archives

1. Library and Archives Canada

Among the largest libraries in the world, Library and Archives Canada functions as the equivalent of the US Library of Congress and the National Archives—combined. To access the site’s collections, scroll down and click on Genealogy and Family History.

Collections here include birth, marriage and death records; acts of divorce from 1841 to 1968; immigration and citizenship records up to 1952; land records from 1763 to 1841; and military records from 1782 to 1947. Some records are linked to digitized images. Click on Census Search for censuses from 1825 to 1931.

2. Nova Scotia Archives

Click on Genealogy, then select Genealogy Guide for information on several kinds of records. Digitized records on this website include land grants from 1765 to 1800 and census, assessment and poll tax records from 1767 to 1838. You can also browse digitized newspapers from 1769 to 2002, but (because you can’t keyword-search them) they’re most useful if you already have a date for an event like a marriage or a death.

From the Archives’ companion website, Nova Scotia Historical Vital Statistics, you can search more than 1 million names, all linked to digitized records—and all free of charge.

As of this writing, the site has birth records from 1864 to 1877 and 1908 to 1923 (including delayed registrations back to 1830); marriage records from 1763 to 1948; and death records from 1864 to 1877 and 1908 to 1973. You’ll also find death records for the city of Halifax from 1890 to 1908. (More-recent records are held by the Vital Statistics Service.)

3. Prince Edward Island Public Archives and Records Office

Under Access the Archives Online, click on “Search Public Archives Material Online,” then on “Search PARO Collections Database.” Here, you’ll find baptisms from 1777 to 1923, marriages from 1827 to 1936, and deaths up to 1968, plus the 1841, 1881, 1891 and 1901 censuses. The collection includes all the key information from the original records, and you can view digitized images of marriage licenses from 1827 to 1888.

When you search by keyword, use a filter to narrow your result by subject (or click Advanced Search to run an initial search for a particular kind of record). “Textual item” will search Supreme Court case files from 1770 to 1959 and petitions from 1780 to 1915.

4. Provincial Archives of New Brunswick

Click on Search and select from the databases, such as: indexes to births, marriages, deaths, burials, passenger lists and land records; gravestone transcriptions; and digitized marriage and Revolutionary War records.

Daniel F. Johnson’s “New Brunswick Newspaper Vital Statistics” has key details from articles published between 1784 and 1896 and covers a whopping 640,305 names.

The Federated Database Search covers several databases at once, but it doesn’t cover everything. You can browse a name index to “Wallace Hale’s Early New Brunswick Probate, 1785–1835,” containing abstracts of 2,371 probate files.

French-Speaking Canada

5. Bibliothèque et Archives Nationales Québec (BAnQ)

Click on “Les bases de données généalogiques de BAnQ.” Then scroll down and click on “Accédez aux bases de données.” Use the Search box to crawl through various collections, including the catalog and digitized census, civil, marriage, death, coroners and land records. For example, you could search on famille LeClerc, LeClerc family, genealogie Trudeau or Trudeau genealogy and add a place name to narrow the scope if you get too many matches. Instead of searching all the databases at once, you could select one to use its customized search form.

If you don’t know French, BAnQ may be hard to navigate and the records may be difficult to interpret. Some pages are available only in French, but you can use Chrome to translate them into English.

6. Genealogy of Canada (Généalogie du Québec et d’Amérique Française)

This free site has a collaborative family tree focusing on French-speaking Canada. You can add information on your own family (along with family pictures) and link it to other users’ data. The family tree is mostly accurate, but since it’s a crowd-sourced database, you should verify the information with other sources. There are errors, and often the list of a family’s children is incomplete.

The site’s forum lets you connect with other researchers, and a directory of Quebec parishes (paroisses) has links to church records on BAnQ and FamilySearch.

7. Genealogy Quebec (Généalogie Québec) $

Created by the Drouin Genealogical Institute, founded in 1899, Genealogy Quebec has tens of millions of historical and genealogical records and images. Their collection includes baptism, marriage and burial records, plus death cards, censuses, tombstones and family genealogies. While they focus mainly on Quebec, coverage extends to New Brunswick and parts of Ontario and the United States.

8. Programme de Recherche en Démographie Historique (PRDH, The Research Program in Historical Demography) $

This remarkable collection includes all baptisms and burials in Quebec’s Catholic church registers through 1861, plus all of Quebec’s marriages (both Catholic and non-Catholic) from 1621 to 1861.

You can perform a cursory search of the index for free, but will need a subscription to access details in records. Since the data here is based on the Drouin Genealogical Institute’s Quebec parish record microfilms, it’s highly accurate.

Drawing on all of those records, the creators have also compiled histories and biographies of Quebec’s early families. Data is displayed in family group sheet format with links so you can navigate around family trees.

PRDH and Genealogy Quebec complement each other. PRDH has “reconstructed” family histories, while Genealogy Quebec has the original parish registers on which those histories are based. So if you subscribe to both, you can view the compiled family histories and the original sources.

Books, Journals and Manuscripts

9. Canadiana

This huge collection includes digitized family and local history books, periodicals, manuscripts and government publications.

A Loyalist soldier in the Revolutionary War, my ancestor James Pennington served in a regiment called the Queen’s Rangers and later settled in New Brunswick. A search on “James Pennington” (use quotation marks to search on a phrase) produces nearly 100 matches. But adding another search term, “Queen’s Rangers,” narrows the results down to just a few.

One of them, an article in an issue of The New Brunswick Magazine from 1899, includes a transcript of a letter written from a jail in Reading, Pa., on 27 July 1780. Captured along with some of his troops by Washington’s army, Sergeant Morris Haycock pleads for help from the Queen’s Rangers quartermaster in New York. Haycock writes, “I with Jerry Ownings[,] John Stephens and James Pennington are here Prisoners of War greatly distressed for want of Necessaries…”

James Pennington had a son, Rev. William E. Pennington, who was a Freewill Baptist minister in New Brunswick. A search on his name as a phrase turns up just a few matches, including a book published in 1902, History of the Baptists of the Maritime Provinces. In addition to a lot of background information on the Baptists of New Brunswick, it has a detailed biography of William E. Pennington. It says that he was born in Queensbury, New Brunswick, in 1804 and ordained in 1832, and that he “organized a score of churches, and baptized more than a thousand converts.”

In addition to names, search on topics related to your ancestors to find materials that might put their lives in historical context. A search on “Queen’s Rangers” produces thousands of matches, one of which is a book by John Graves Simcoe, the commander of the Queen’s Rangers. A Journal of the Operations of the Queen’s Rangers gives a detailed chronology of the regiment’s movements and the battles it fought in during the Revolutionary War.

These military histories can help answer persistent genealogy questions. A common problem with Loyalist genealogy, for example, is figuring out where the Loyalist lived before the war. Indeed, the earliest reference to James Pennington in muster rolls says that he was taken prisoner on 18 July 1778, but the record doesn’t say where. But Simcoe’s account says the regiment was located in Burlington and Monmouth Counties, N.J., in late June 1778, and at Kingsbridge, N.Y., on 15 July 1778. Maybe James Pennington enlisted at one of those places.

Loyalists

10. The On-Line Institute for Advanced Loyalist Studies

The creation of Revolutionary War re-enactors Todd W. Braisted and John Korchok, this site has extensive resources for researching Loyalist ancestors. The Loyalists were those who served in a military capacity for the British during the American Revolutionary War.

The site includes transcriptions of muster rolls, land petitions and other records. Click on Search Our Site to investigate a name or topic. The site recommends you search on just a last name because given names in the records are often abbreviated or omitted.

A search on Pennington Penington, selecting “Match ANY word” to look for both spellings of the name, turns up just two matches. One, a muster roll of Captain Kerr’s Company in the Queen’s American Rangers, says that James Pennington was taken prisoner on 20 July 1779. So he seems to have spent considerable time as a prisoner of war!

Click on Military for a list of regiments, regimental histories and other records, as well as information on Black Loyalists and Loyalist uniforms and clothing. Click on Genealogy for hints on researching Loyalist ancestors.

The Big Four Genealogy Websites

11. Ancestry.com $

Learn about Ancestry.com’s search options

You can search all of Ancestry.com’s indexed record collections at once, but it’s worthwhile to focus on those most relevant to your family history. From the main menu, click Search > All Collections, then North America > Canada under Explore by Location. You’ll find links for specific provinces, as well as a link for all of Canada. You can also search Canadian collections in the Card Catalog (Search > Catalog, then add a filter for Canada).

The collections here include decennial censuses from 1851 to 1931, plus special censuses of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta (1906 and 1916) and Newfoundland (1921, 1935 and 1945). And “The Canadian Incoming Passenger Lists, 1865–1935” collection has digitized records of 8.3 million people arriving in Canadian ports.

Among the site’s vital records are digitized birth, marriage and death records for New Brunswick, Newfoundland, Ontario, Prince Edward Island, Alberta and Nova Scotia. Ancestry.com also imported more than 30 million indexed obituaries from Canadian newspapers, courtesy of its sister site Newspapers.com.

Those researching Québécois ancestors have extra reason to celebrate. The mostly-French “Quebec, Canada, Vital and Church Records (Drouin Collection), 1621–1968” includes more than 34 million records, mostly from Catholic church registers but from other denominations, too. “Quebec, Canada, Notarial Records, 1637–1935” also has more than 16 million records, including marriage contracts and wills.

12. FamilySearch

Learn about searching at FamilySearch

Select Records from the Search tab and, under Search by Place, enter Canada in the box and press enter. That takes you to the Canada search page, which has various research tools. Click “Guided Research for Canada,” then select a province to get help for finding birth, marriage and death records there. Under “Guided Research” is the Learning Center with links to video learning courses covering Canadian census records, Quebec research and other topics.

On the right of the Canada search page, you’ll find a form to search all the site’s indexed historical records at once. Keep scrolling, and you’ll find you can filter by record collection: census, church and vital records, etc.

Further down are the image-only historical records. Yes, it may take a while to browse unindexed records, but you could make important discoveries in them. Likewise, the Catalog Material in the third section lists more resources, some of which have yet to be put online.

13. Findmypast $

Click Search and select Canada from the options in the Where box to limit matches to Canadian records. Or you can browse through Canadian record collections by clicking Search at the top of the page, then All Record Sets. In the Filter By box, select Canada from the drop-down options. The collections are arranged by size, but you can sort them by a category, subcategory or name by clicking the respective heading.

Key Canadian record collections on Findmypast include census records from 1851 to 1911 and indexes to vital records and gravestones. You can also browse some unindexed records (marked with “Browse” in the title), such as Manitoba probate records and British Columbia estate files.

14. MyHeritage $

Read six strategies for searching at MyHeritage

To browse through the Canadian record collection titles, select Collection Catalog from the Research tab and Canada under Refine by Location. The collections are sorted by size, but you can sort them alphabetically or by the date they were last updated. Major collections include census records from 1851 to 1931, Quebec marriage records with images from 1926 to 1997, and vital records indexes for New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Ontario.

The site also has a large collection of historical newspapers. To search them, select Newspapers from the Research tab. Scroll down and click on View All. Under “Refine by Location,” select Canada.

Searching on the name of my ancestor William E. Pennington in the former, I get a match on an ad in the Ottawa Daily Citizen of 23 January 1886. A testimonial quotes Rev. Pennington in a product testimonial (“Ayer’s Sarsaparilla has made a new man of me”) and notes it cured him of his “General Debility.” Coming from a man of the cloth, that should be a persuasive recommendation! (Never mind that Pennington had been dead for almost two years by the time that paper was published….)

Conclusion

With so many historical records, books and newspapers now online, searching for your Canadian ancestors has never been easier. The big genealogy websites have plenty to offer, but don’t overlook the unique online offerings of archives, organizations and individuals. Take advantage of all the sites described here that might be relevant to your family history research.

Related Reads

A version of this article appeared in the March/April 2021 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: October 2024