Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

In this article:

3. Research tribal culture and history

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

“Great-great-grandma was a Cherokee princess” tops many a list of genealogy myths passed down in families. Although the Cherokee didn’t actually have princesses, such stories may hold a nugget of truth. Perhaps the clan that hands down this tale does have an American Indian somewhere on the family tree.

More than 4 million people claimed Native American ancestry in the 2000 census. The US government officially recognizes 562 tribes, making them eligible for certain rights and benefits. Starting in the 1850s and ’60s, the government began setting aside land for tribes that signed treaties; the Department of the Interior now oversees about 310 reservations. Each tribe is self-governing, with a unique history and culture. Religious practices, customs and family structures vary among tribes, even among those in the same geographic areas.

But not everyone with American Indian heritage is a tribal member (generally, you must have a certain amount of “Indian blood” for membership), and not all tribal members live on reservations. All this can make for a challenging genealogy research proposition. Thankfully, American Indian groups and the individuals associated with them—whether officially or not—have enough shared history that some common research techniques and resources can help you trace them. Use these strategies to explore your family tales of Indian ancestry.

The Cherokee princess myth may have its origins in prejudice. Cherokee is among the largest American Indian tribes and its members intermarried widely, thereby increasing the likelihood that a given modern-day American will have Cherokee ancestry. For those who frowned upon a white male ancestor marrying an Indian woman, elevating the woman’s status to princess might’ve made the truth easier to swallow. Follow these steps to begin getting at the truth.

1. Investigate the story

Although many tales are embellished or flat-out false, a truth might be couched somewhere within the story. What led family members to believe and repeat the story? Did ancestors live near Indian tribes? Does a family photo show off high cheekbones? Did Grandma always say so? Try to get at the origins. Oral history interviewing is an important first step. Ask siblings, cousins, parents, aunts and uncles if they’ve heard tell of the name of a tribe, whether the rumored Indian ancestor lived on a reservation and when, and what his or her Indian name was. Also ask where the relative’s family lived and how they moved around the country.

2. Listen for a tribe name

To research Indian heritage, it’s vital to determine the tribe your ancestor was affiliated with. Sorting out an Indian family can be tricky: The use of kinship terms (sister, uncle, father) can differ from today’s mainstream usage, and from one tribe to another. If you have stories of American Indian ancestry but haven’t been able to identify a tribe, try asking about the ancestor’s language, religious beliefs and ceremonies. As you read about different tribes, some of these cultural traits may help you make a match. If oral tradition gives you the name of Great-grandma’s tribe, and you know all the places she and her parents lived during their lifetimes, your next step is to make sure people of that tribe would’ve been in those localities at the right time periods. For example, if the story says that Great-grandma was a Penobscot, but you know from other research that she lived in Colorado in 1860, you might have a problem: The Penobscot tribe is centered in Maine and was never pushed West; few Penobscots would’ve lived in Colorado in 1860. Click here for a list of Indian tribes by state.

Realize, too, that a tribe the federal government formally recognizes today may be one of several communities descended from one tribe, so you’ll want to learn how your ancestor’s tribe merged with or split from others over the years. The Seminole of Florida were composed of Creek, Muskogee and other Southeastern Indians, as well as African-Americans who’d escaped slavery. You also might find that tribal members called themselves a name different from how they’re known to others. The Navajo, for example, refer to themselves as Diné, meaning “the people.”

3. Research the tribal culture and history

America’s stormy history with indigenous tribes spanned centuries and countless conflicts. Searching for Native American roots means honing your skills as a historian. Without a basic understanding of tribal history and its historical context within the larger perspective of American expansion, it will be far more difficult for you to dig out your roots. As a Native American researcher, you may become as adept at unraveling the ins and outs of the Grattan Massacre as a Civil War buff is at explaining the ramifications of Gettysburg.

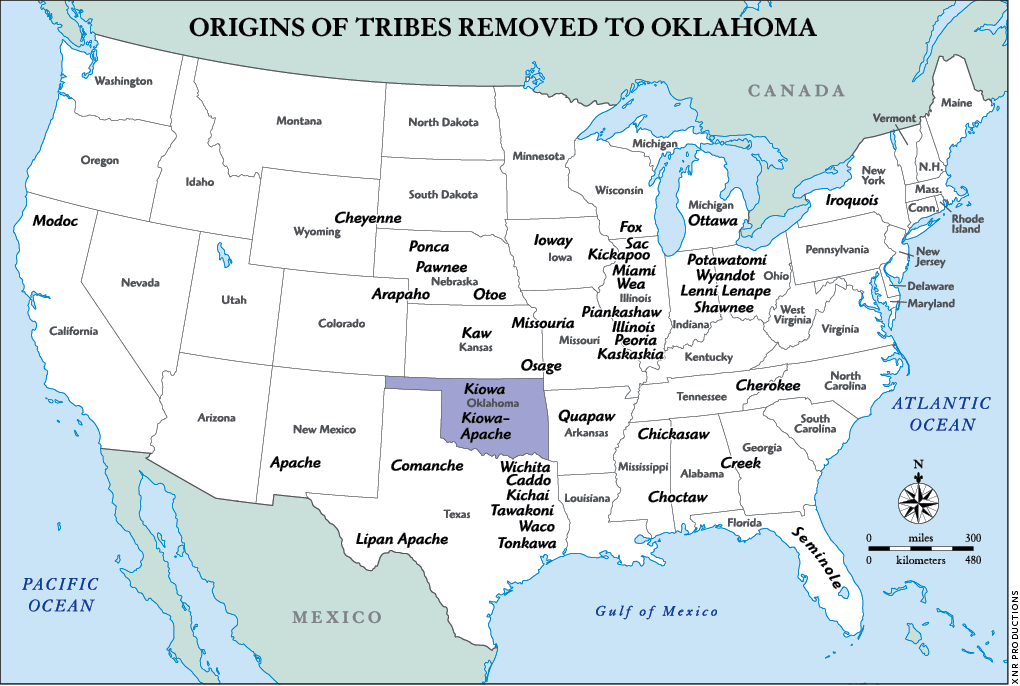

It’s important to learn the history of the tribe or tribes you think an ancestor belonged to. Many tribes were partially or completely “removed”—sometimes more than once—to a new locality. Beginning in 1838, for example, most members of the Five Civilized Tribes (Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek and Seminole) were forcibly removed from their traditional home in the Southeast to Indian Territory (Oklahoma today) along a route now called the Trail of Tears.

In some cases, you’ll need to know the migration patterns of a particular tribe or the many areas in which it was “resettled.” For instance, over a 150-year time span, the Cherokee lived in the Carolinas, Georgia, Arkansas and Oklahoma.

Investigate the clues

If you’re not sure you have American Indian ancestry, several clues could spark your search: Grandma may have told you her grandfather had Indian blood. Maybe you came across an M, B, MB or I in the color column of census records. (An M stands for mulatto, B for black, MB for mixed blood and I or In for Indian.) The mark could be arbitrary — or it may indicate Indian ancestry. Diaries, business transactions or other records might reveal an ancestor’s association with local American Indians. The ancestor’s movements might correlate with a tribe’s migrations.

To investigate these clues, you’ll need to place your ancestor in a tribe, place and time period. Begin by working backward from what you know, talking to relatives and documenting recent generations.

Next, narrow your search to a tribe by studying your ancestors’ historical context. Create a timeline of places your family members lived, and learn about the history of Indian tribes in those places. Consult the books on the next page and look for tribal histories in libraries, especially those of major historical societies and universities. You’ll want to answer these questions:

- What tribes were in an area when your ancestor lived there?

- What migrations (both forced and voluntary) took place?

- What reservations were in the area, and when?

American Indian traditions emphasize oral history—stories of people and customs passed through generations. You might rind that a family member was involved in art oral history project such as the American Indian Research Project at the South Dakota Oral History Center, with archives of nearly 2,000 interviews with Northern Plains Indians. Check with the area historical society or library—even if you don’t find an interview with an ancestor, you’ll discover valuable tribal history.

Written by Paula Stuart Warren

Tribe traditions

If your family belonged to one of the Iroquois linguistic groups, you’ll learn that the culture was matrilineal — descended through the female line. Children belonged to their mother’s clan or tribe. Similarly, in the Ojibwa tribe, women controlled their homes and the family’s property. Hopi women owned the property and their husbands worked to benefit the wife’s family.

You may also encounter surprises with naming patterns and kinship systems. At birth, Plains Indian babies were given names that had a connection with their clan. Later in life, however, those children often received another name that reflected their personalities or deeds. Europeans frequently gave yet another (Anglo) name to the American Indians they interacted with. In the Wasco and Wishram tribes of the Interior Plateau, children received several new names during the course of their lives as they achieved higher rank or social position. Nicknames were also common.

Regional libraries or historical societies are a good bet for tracking down information on the tribes in your ancestor’s area. The genealogical periodicals that cover the region where your ancestor lived may contain sought-after information. One of the best indexes to these periodicals is the Periodical Source Index (PERSI) (searchable at genealogical libraries and by subscription to ). PERSI is a subject index that covers genealogy and local history periodicals since 1800; it contains more than 1.1 million index entries from nearly 6,000 titles. Using PERSI, you can find articles on subjects ranging from Ojibwa decorative quillwork to Seminole Negro-Indian Scouts, 1870-81.

Equally important are firsthand narratives such as those found in Wisdom-keepers: Meetings with Native American Spiritual Elders (Beyond Words Publishing). In this book, 18 elders from different tribes discuss the location of spiritual places, the names for native homelands, historical details and sketches of family life. Stories such as that of Hopi Thomas Banyacya can offer insight into your ancestors’ culture: The Hopi believe that Big Mountain on Black Mesa in Arizona is the center of the universe, and that the spiritual ceremonies performed on the mesa help determine the balance and harmony of nature. “We’re the first people here,” says Banyacya in Wisdomkeepers. “We’re the aborigines of this continent. We live here with the permission of Great Spirit.”

Written by Nancy Hendrickson

4. Start with yourself

No single record will give you a complete history of your American Indian ancestors. You won’t even stick solely to records specific to Indians. In many ways, Indian research is comparable to that for any other ethnic group: Start with basic records, such as census and vital records, and work methodically backward from yourself, one generation at a time. As your research progresses, you also begin to zero in on sources that are unique to your ancestor’s ethnic group, nationality, religion, geographic area or time period. When you find an ancestor with a reasonable point of likely connection with an organized community—in this case, an Indian tribe—that’s when you begin to focus on that tribe’s history and records.

We’re not saying that tracing Indian ancestors is just as easy as tracing anyone else. As for many ethnic groups, historical prejudice has created significant hurdles. For example, many American Indians and their descendants tried to hide their heritage. If Great-grandma assimilated into general society—by marrying someone of European descent, for instance, and adopting mainstream cultural practices—researching your American Indian origins will likely be tougher. If you’re methodical and work back in time, you’ll be less likely to miss critical clues that link you to the American Indian ancestor. It’s also important to study the area where your Indian ancestors lived, because they interacted with the surrounding community. The community’s history and records may tell you about your ancestor.

5. Know what to look for

Before you dive into American Indian records, know what to expect — and what to look for. You’ll see terms such as Alaska Native, American Indian, Native American, First Nations (generally used for Canadian tribes), tribe, hand, community and clan. Labels used to refer to American Indians vary by time, tribe and location. Names vary, too. US government personnel often called American Indians by Anglicized names (remember Take the Tail’s being dubbed Lucy Pretty Eagle). Language and education also affected how names were recorded. So expect to find multiple names and spellings for each ancestor.

American Indians who assimilated into the general population — by choice or by force — might not be called Indians or appear at all in Indian records. If your ancestor’s tribe wasn’t recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) — the federal agency formed in 1824 to guide government relations with tribes — you’ll find few BIA records for your ancestor. Instead, concentrate on census documents, newspaper accounts and the other records mentioned here.

Visit Indians.org for a list of recognized tribes and here for nonrecognized tribes. BIA field offices can be found on the BIA website. BIA jurisdictions have changed over time, so consult Edward Hill’s Guide to Records in the National Archives of the United States Relating to American Indians (National Archives and Records Administration) for help.

Each tribe has a unique history, so a record created for one tribe might not have been kept as carefully — or at all — for another. Inconsistencies in recording tribal affiliation, degree of Indian blood and family relationships are common. One BIA agent may have laboriously recorded a tribe’s births and deaths. A lazier agent might have copied the previous year’s data, increasing each person’s age by one. Widely scattered tribes made contact difficult, and language was often a barrier. Ancestors sometimes gave conflicting information, or embellished tribal affiliations to qualify for government aid. In some American Indian communities, spiritual beliefs meant the dead weren’t spoken of. Not until the late 19th to early 20th centuries did records detail American Indians with reasonable reliability. But don’t give up. If you’ve exhausted all means of finding one of the following record types, look for another.

Written by Paula Stuart Warren

5. Review the records

No one likes government red tape and bureaucracy, but you must admit that you smile upon discovering it created a record with your ancestor’s name on it. Though Indian tribes didn’t often keep early records on themselves, the US government did its best to document tribes, especially from the 1880s on. These massive collections, combined with standard genealogical resources, make Indians living with tribes the most extensively documented post-1885 US ancestors. The records that were created and their availability today varies depending on the tribe and the time period. Records might be at National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) research facilities, with the Department of the Interior and its Bureau of Indian Affairs, or at other federal departments. Some of the significant record collections have been preserved on microfilm or microfiche, but many are available only in their original paper form.

Here are details on major resources covering American Indians:

US Censuses

One of the simplest ways to identify an American Indian ancestor is in the census. The 1860 US census identified Indians in the general population (but not Indians living on reservations) for the first time with “I” or “In” in column six of the census schedule. In the 1870 and 1880 censuses, Indians were again enumerated in the general population. Also in 1880, a special census (found on NARA micropublication M1791) enumerated some Indians in California and the Washington and Dakota Territories. For more information, see NARA’s website.

The 1890 federal census, of course, was virtually destroyed due to a fire. For the 1900 and 1910 censuses, enumerators recorded information about American Indians on special schedules called “Inquiries Relating to Indians,” detailing people living on reservations. These documents are valuable because they ask the tribe and degree of Indian blood (for example, half or one-quarter) for the individual and his or her parents. Indians were enumerated along with the general population in 1920 and 1930, noted with “I” or “In” in the color or race column.

From 1885 to 1940, Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) agents were supposed to take annual censuses on each federal reservation. These actually occurred more randomly than annually. Visit NARA’s website for more information and to see what records are available for each reservation. The schedules are on 692 rolls of microfilm in NARA Record Group 75, film M595. They’re also digitized and searchable on the subscription sites Ancestry.com (as part of the Census and Voter Lists collection) and Fold3.

The enumerations usually give the names of the tribe, reservation and BIA agency; nearest post office; number of people living in the household; the type of dwelling; and each person’s Indian name and English name, relationship to the head of the household, marital status, tribe (sometimes with the degree of Indian blood), occupation, health, education and land ownership.

Special Censuses

Almost all reservations were enumerated at some point, but there are notable exceptions. When the Five Civilized Tribes were relocated to Indian Territory, legislative action changed their governance and record-keeping. One result: You won’t find them in the annual Indian census rolls. But they may be in special censuses, such as the 1880 and 1890 Cherokee censuses taken in Oklahoma; 1885, 1896 and 1900 Choctaw censuses; or a 1900 Chickasaw census. The Family History Library (FHL) and the Oklahoma Historical Society have these censuses on microfilm. Or you might find tribal members who stayed in the East on Indian census rolls of the Eastern Cherokee of North Carolina, for example, or the Choctaw of Mississippi (both are on FHL and NARA microfilm).

The free site AccessGenealogy links to a number of census indexes and records for various tribes and places. Treaty and annuity rolls These are usually the only federal documents naming tribal members prior to the establishment of reservations. Annuities were goods and/or money the government paid to tribal members in fulfillment of treaties. Even Indians who lived outside reservations—and their descendants—would often identify with the tribe again to apply for aid. Knowing the history of the tribe will help you identify times when the government paid claims.

Dawes Rolls

A good starting point if you have Cherokee ancestry is the Final Rolls of the Five Civilized Tribes, more commonly known as the Dawes Rolls. In 1898, Congress authorized a commission to determine enrollment in the Five Civilized Tribes, whose members would receive land allotments. Henry L. Dawes headed the commission, which enrolled more than 101,000 tribal members between 1898 and 1914.

Records include tribal census cards, available on Fold3, in Ancestry.com’s census collection, and on NARA microfilm. NARA has the original census cards, as well as application jackets with enclosures (affidavits, correspondence and other evidence of eligibility) and allotment jackets. Access NARA’s index to the Final Rolls of approved individuals online. For help using the index and requesting an ancestor’s file from NARA, see NARA’s tutorial. Footnote also has the digitized application packets.

The commission rejected more than 200,000 applicants. Rejected Cherokee and Choctaw applications and census cards are at NARA’s Southwest regional facility in Fort Worth, Texas. In 1906, Guion Miller was charged with determining who was eligible for funds under treaties with the Eastern Cherokee in the 1830s and 1840s. About 90,000 applicants are named in the Guion Miller Roll index, which is searchable on Footnote; it’s also on NARA and FHL microfilm. Eastern Cherokee applications filed with the US Court of Claims are on Fold3, too.

Following are the three main types of records in the Dawes rolls:

- Census cards, also known as enrollment cards, list each enrollee’s tribe, blood quantum (the percentage of “Indian blood” inherited from ancestors), name, age and sometimes family members. Each person on the card was assigned a tribal roll number.

- Enrollment packets include transcriptions of interviews, application forms and other documentation of a person’s eligibility for tribal membership.

- Land allotment packets document the land an enrollee received. They contain the enrollment number and name of the applicant, names of his extended family, the land’s location and legal description, and other documents.

Follow these steps to search the Dawes Rolls. Some terms you may see used to describe enrollees include:

- By blood: the person has some degree of Indian blood

- By marriage: a person, usually white, is married to an Indian applicant

- Minor or newborn: a child born to the applicant after the initial application was made, but before the rolls were finalized in 1907

Written by Nancy Shivley

Bureau of Indian Affairs records

Bureau of Indian Affairs records The Department of the Interior and its new Office of Indian Affairs (later renamed the Bureau of Indian Affairs, or BIA) took over tribal relations from the War Department in 1839. Each BIA field agent was assigned a geographic area or “agency.” Remember that BIA records generally identify only Indians living as part of a tribe that had recognized ties with the federal government. Many tribes didn’t, and many individuals dropped their tribal ties and assimilated into the general population.

BIA letters, reports, administrative records and Indian school records are in NARA’s custody. Most cover 1830 to about 1970, and are usually arranged by tribe. The majority of administrative records are located in NARA’s Washington, DC, headquarters, as are the bulk of tribe-related records before 1885. Most post-1885 agency records and correspondence BIA agents received, as well as Indian school superintendents, are usually at the NARA regional facility closest to the location of that agency. Footnote has records of the Cherokee Indian Agency in Tennessee from 1801 to 1835.

Reports and inquiries

Correspondence files are filled with letters including reports and inquiries from BIA agents; inquiries and requests from Indians, missionaries, traders and other government entities concerning tribes or individuals; and applications for employment in the Indian Service at every kind of job from blacksmith to agent. Heirship records document who was to receive a deceased Indian’s land. Because few BIA records are digitized, microfilmed or even indexed, you’ll probably have to research in person at NARA or hire a local researcher.

Letters

Letters the Office of Indian Affairs received between 1824 and 1881 are on NARA microfilm series M234, with copies at the FHL and other major research facilities. You can use NARA’s microfilm catalog (click here and then click Microfilm) to pinpoint rolls of film pertaining to your ancestor’s tribe and time period. A pamphlet included on the first roll of the series explains how to search these letters by agency and individual names. Letters the BIA received from 1881 to 1907 are in paper form at NARA’s main research facility in Washington, DC. The archives has a series of indexes for these letters called “Microfilm Publication P2187: Office of Indian Affairs/Bureau of Indian Affairs: Indexes to Letters Received, 1881-1907.” (It’s not listed in NARA’s online microfilm catalog.) Check these indexes for your ancestors’ names and the tribe name. This is especially helpful for information on Indians’ inquiries about claims or payments to tribal members.

Around 1900, most federal departments and agencies stopped filing their incoming correspondence chronologically and began using a subject system with decimal codes. Most of NARA’s post-1907 BIA correspondence is filed that way in “Central Classified Files” arranged by agency, then by subject.

School censuses

From 1910 to 1939, the BIA took censuses of Indian schools, institutions where Indian parents were encouraged or compelled to send their children. Censuses list the names of children ages 6 to 18, their sex, tribe, degree of Indian blood, distance from home to school, parent or guardian, and school attendance. They often include the mother’s maiden name. These schedules usually are in the NARA regional facility covering the area where the school was located. For a good overview of other federal records related to American Indians, see Guide to Genealogical Research in the National Archives, 3rd edition (NARA, out of print). If your ancestor was a member of the Five Civilized Tribes, also see George J. Nixon’s list in the Native American Research chapter of The Source, 3rd edition (Ingram Publishing Services).

Missionary records

For hundreds of years, missionaries of many religious denominations made it their life’s work to “save” Indians through conversion. That may or may not have been beneficial for the Indians, but it can help genealogists. Missionaries’ records on christenings, deaths and marriages may be in a local church’s record books, or in a journal tucked away in a library or archive. Read tribal histories to find our what missionaries were active in your ancestors’ area and time, then find our where that denomination keeps its records. Check area historical societies, too.

Written by Paula Stuart Warren

Military records

American Indians have been serving in the US military since the Revolutionary War. You can find them in many of the same service and pension records as the other soldiers in your family tree. But Indians did provide some unique services, creating additional records held at the NARA.

- Code Talkers: The Navajo “code talkers,” who used their native language to encrypt military communications during World War II, are well known. During both world wars, Lakota, Cherokee, Choctaw and other Indians also served as code talkers.

- Scouts: Sometime hired, sometimes enlisted in the Army, Indian scouts served in the American West from just after the Civil War until 1947.

Written by Nancy Shivley

Heirship and probate files

If your American Indian ancestor owned land, it had to be dispersed after he died — which may have resulted in an “heirship” proceeding. BIA records contain a wealth of heirship case files and correspondence. The files can yield golden nuggets of information: People who knew the deceased and the family were interviewed about relatives, spouses, siblings and earlier generations, resulting in a wonderful family picture.

Written by Paula Stuart Warren

Newspapers

Like many ethnic groups, American Indians had special-interest newspapers. Missionaries in Dakota Territory published lapi Oaye (Word Carrier) from 1871 to 1939. It covered births, marriages, deaths, baseball, government programs and news from a wide area, with emphasis on Nebraska, the Dakotas and Minnesota. An English version was published from 1884 to 1937, but you’d need a translation dictionary, such as Stephen Riggs’ A Dakota-English Dictionary (Minnesota Historical Society), to read other issues. For listings of similar newspapers, consult Native American Periodicals and Newspapers, 1828-1982 by James P. Danky (Greenwood Press).

Mainstream newspapers varied in their coverage of American Indians, depending on current events, politics and proximity to reservations. Check libraries near your ancestors’ homes for newspapers that ran articles about local tribes. For information on historical newspapers by state, visit Newspapers.com.

Written by Paula Stuart Warren

Vital records

Although it’s worth searching for earlier records, many American Indian births, deaths and marriages weren’t documented at vital-records offices until the 20th century. Most BIA vital-record-keeping on reservations began in the late 19th century. The years and types of records vary by tribe and BIA agent. You may find duplicate vital-record entries, especially for the 20th century, when agents were more thorough and may have forwarded details to the county courthouse or a state government office. The FHL (search the catalog by place name and vital records category) and regional branches of NARA hold many BIA viral records.

Whether your Indian ancestors wed in a church or by tribal custom, a marriage record could appear in local church records, the county courthouse or a BIA agent’s correspondence, likewise, divorces might have happened at the courthouse or by tribal custom. Traditional American Indian marriages and divorces didn’t leave much of a trail, but you can find evidence in census, heirship and other records.

Despite conflicts between Indians and other groups, intermarriage was common. In areas with an active fur trade, such as present-day Minnesota, British and French Canadian traders married Indians; so did Buffalo Soldiers in Western and Plains states, and white settlers who pushed west into Indian territories. In the South, American Indians intermarried with African-Americans. Members of different tribes also intermarried — so you may need to cheek records of both tribes.

Written by Paula Stuart Warren

Searching records further

Your ancestor’s tribe may have enrollment office records of tribal members, tribal histories and recorded oral histories—or it might’ve compiled little documentation and limit access to it. Once you’ve determined your ancestor’s tribe, you can learn about its resources from its Web site or by contacting the tribal office.

Scattered among hundreds of repositories are records created by many institutions and individuals that could help your Indian research. Those include historical periodicals, church and cemetery records, newspapers, school records, diaries, maps, ledgers, biographies, and historical and ethnological series of publications. One such series is the Smithsonian Institution’s 20-volume Handbook of North American Indians, which you can find at many large libraries (see what each volume covers here).

In many cases, county government records, local histories, historical society collections, newspapers, USGenWeb county resources, and other state and local history sources have information on Indians in the area. They’ll also tell you about Presbyterian, Episcopalian, Catholic or other denominations’ missions on or near reservations—which may lead to registers of sacrament recipients, missionary correspondence and reports, school records, and mission or denominational newspapers. Find microfilm by running a place search of the FHL catalog and looking for a church records heading. Researching your American Indian ancestors can be challenging, but as you’ll see, the rewards of exploring your family’s true heritage are great.

6. Carefully consider DNA

Ads for companies that test your DNA for American Indian ancestry sometimes sound like a magical shortcut to your American Indian heritage. In reality, DNA testing is genealogically useful, but usually in a more limited way. Geneticists can analyze part of your DNA for similarities to that of American Indian populations.

The test you’d take depends where on your family tree you think the American Indian was: If the Indian was a woman on your maternal line, you’d take a mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) test, which assigns you to a haplogroup. Otherwise, you’d take an autosomal DNA test, which looks for certain types of genetic markers common to modern Indians. Either way, it’s unlikely the test would link you to a specific tribe, a recent time period, or any one individual.

In addition, ethnic DNA testing is still a somewhat controversial science. Genetic genealogy tests are best used as a clue, not proof, of Indian ancestry. But DNA testing still may be useful because of the growing numbers of people participating. If your test results match someone else’s, that person’s ancestral information will help you narrow your focus and find your common ancestor—and possibly, the American Indian at the heart of your family stories. Genetic genealogy testing is rapidly changing, promising even more breakthroughs for the future. You can read up on these developments in the December 2009 Family Tree Magazine.

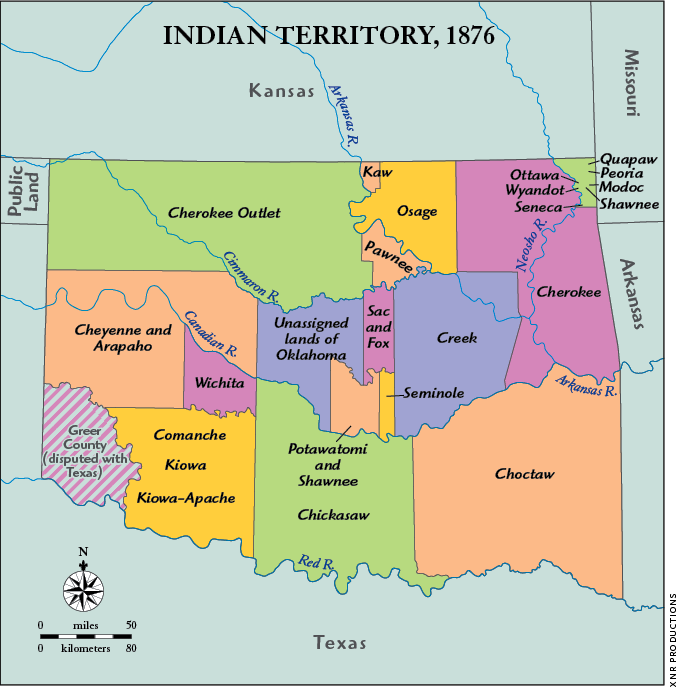

Many Indian nations and tribes that were allocated land in Indian Territory (above). Located in what’s now Oklahoma (from the Choctaw term for “land of the red people”), the territory progressively shrank as the government opened land to settlement. In 1907, Indian Territory became part of Oklahoma (below).

7. Try searching on-site

One challenge of researching American Indian roots is that much of your work must be done on site at NARA and other repositories. The BIA doesn’t keep many historical records, hut most of its archives are available at NARA, as are military, land, school and other relevant records — which you also can get via the FHL. NARA’s College Park, Md., location also holds Department of the Interior records, maps and photographs.

NARA’s regional facilities house BIA records pertaining to the states each serves: the Fort Worth Region has records from Oklahoma, for example. On NARA’s Web site, you can determine which centers have which records: From the home page, click Research Room, then Guide to Federal Records, which details records’ scopes and locations. For example, check out Record Group 75, Records of the BIA. But remember: Not all federal records of Indians are in this record group. Study the online guide — it’s more up-to-date than the published version.

You also could hit pay dirt at smaller repositories, particularly in local, state or regional archives and historical society libraries. Check ones in the areas your ancestors’ tribe inhabited — including the places they migrated to. To research Southern and Southeastern tribes, many of which were forcibly removed to what’s now Oklahoma, visit the Oklahoma Historical Society. You’ll find information about the society’s records on nearly 70 tribes, especially the Five Civilized Tribes. If you’re searching for Cherokee ancestors, try the Cherokee Heritage Center.

Don’t let the notion of trekking to distant libraries and archives discourage you. Instead, remember that stories like Take the Tail’s are waiting for you to discover them. With diligence and determination, you can bring the details of your own ancestors’ lives out of obscurity. The research is challenging, but you can persevere — just as your ancestors did.

Information in this article appeared in the April 2004 (Warren), November 2009 (Warren/Carmack), October/November 2016 (Shivley) and October 2001 (Hendrickson) issues of Family Tree Magazine.

Related Reads

ADVERTISEMENT