Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

On a roll

Once you’ve gathered all your home audio, video and film, the first task is to figure out just what you’ve got. Kevin O’Neill of VidiPax (800-653-8434, <www.vidipax.com>), a New York-based media restoration company, says you’re likely to come across these common formats:

ADVERTISEMENT

• Reel-to-reel audio: German scientist Fritz Pfleumer introduced magnetic audiotape back in 1928. By the 1950s, ¼-inch tapes on reels of varying sizes emerged as a popular consumer format.

• 16 mm and 8 mm film: Also in 1928, Eastman Kodak introduced color 16 mm film, an innovation that made cameras and projectors affordable to our affluent ancestors. The home-movie trend really took off after 1932, though, when Kodak “split” 16 mm film, creating 8 mm film. With twice as many perforations on each side as 16 mm film, 8 mm could run four times as long as its predecessor. This film caught on immediately, and Kodak made cameras average Americans could afford.

• Super 8 film: This cartridge-loading film for consumers and professionals hit the market in 1965. Super 8 created larger pictures than regular 8 mm film, and the cameras had electric motors (no winding necessary). Undeveloped Super 8 comes in a 2×2-inch cassette; developed, the film measures about ¼ inch wide and is wound on a reel about the size of a your hand.

ADVERTISEMENT

• ½-inch reel-to-reel video: Popular in the late 1960s and early 1970s, this was the first commercially available video format. It’s the same size as modern VHS videotape, except the tape is an open reel rather than enclosed in a cassette.

• Betamax/VHS videotape: Sony unveiled Betamax, the first widely used consumer video format, in 1976. It quickly took a back seat to a similar format, VHS, released by JVC and others that same year. Betamax was finally discontinued in 2002; VHS is just now being eclipsed by DVD as the most successful home-video format.

Besides pinpointing the type of medium you have, you’ll want to identify what memories it holds. Film is light captured on emulsion-coated plastic, which reveals an image when light shines through it. If your relatives didn’t label their film, you can figure out exactly what’s on it by simply holding it up to a light source. But before you unfurl it, check out the casing: If it’s broken, that’s a sign the film may be damaged. Next, examine the rolled-up film for musty or vinegarlike odors, which indicate fungal damage, or discoloration, which indicates chemical breakdown. If you notice any problems at first glance, be careful: Some material may be too delicate to handle, and simply pulling out the film could cause further damage. If the film appears to be in good condition, gently open one of the reels, handling it by the edges. Then hold it up to the light and review a few frames. You may recognize people or places that will tip you off to what’s on the reel and when it was shot.

Magnetic media, such as reel-to-reel audio and video, consist of magnetic signals captured on magnetic tapes. They require a player to translate the signals into sounds or images. If a tape isn’t labeled, you’ll have to listen or watch to know what’s there. But don’t pull out the reel-to-reel player just yet — if you play back something that’s damaged, you might ruin it permanently. To assess the condition of audio and video tape, follow the same process you used for film: First examine the casing and the tape for damage. You won’t be able to look at the tape if it’s encased in a cassette, as Betamax and VHS are (though you can flip up the edge of a VHS tape case and inspect a small section of the tape). But with open reel tapes, you can search for dust and dirt, foreign deposits, scalloped edges and color variation, all of which indicate possible damage.

Tape measures

Now that you have a better idea of what you’re dealing with, you have two goals: to make sure the original memories exist for future generations and to enjoy those memories today. To achieve these goals, your next steps are cleaning and restoration, and transferring the footage to a preservation format.

Cleaning and restoring film requires a particular expertise and should be left to professionals, such as Canadian audio-restoration guru Graham Newton (416-444-3444, <www.audio-restoration.com>) or RPG Productions (818-848-0240, <www.rpgproductions.com>), a California-based film production company that also does restoration. Film can have any number of problems caused by factors from natural aging to water or fire. This damage may not be immediately obvious to the novice, and if you can spot it, you still need the knowledge and specialized materials to repair it. The experts at the Association of Moving Image Archivists (AMIA; 323-463-1500, <www.amianet.org>) recommend that even professional archivists consult a restoration guru when they find tapes in questionable condition.

Next, you need to create a “preservation master,” a copy that ensures the integrity of the original medium. For example, film should be transferred to film, and video to video whenever possible. You’ll use this preservation master to make a single “dupe” (duplicate copy). Duping causes “generation loss,” which means each time you copy from a tape or film, a little bit of the original information is lost. Place audio and video memories inside a water-resistant container; put tails out for reel-to-reel formats and store cassettes vertically, as you would books on a shelf. Keep the container in a cool, dry place.

Should you transfer recordings to an analog or digital master? Restoration specialist Newton says digital is preferable because you’ll experience no generation loss from copy to copy, or from one digital format to another. And though experts still worry about technological obsolescence (will we still have gizmos to read those MPEG files in 25 years?), analog playback equipment promises to become scarcer, too.

Reformatting your entire audio and video archive can be overwhelming and expensive. If you can’t do it all at once, deal with the most damaged media first to quell further deterioration. Then tackle the oldest formats, as they’re at the greatest risk of breaking down and their playback equipment may become obsolete.

From your duplicate copy, you then can make a viewing copy on any medium you like. Think cassette tape, VHS or DVD, all of which give you unlimited access to the content without compromising the original medium. To find companies in your area that provide transfer services, look for video production services in the yellow pages or on the Internet.

You easily can transfer some clean, damage-free media at home. To make cassette tapes, hook up your audio player to a cassette player with an RCA line. Copy VHS or Betamax tapes by connecting the player to your digital camcorder. And though it’s less than ideal, you can use a camcorder (with a slow shutter speed to eliminate flicker) to shoot a film on a projection screen.

Digital distribution

Now that you’ve restored, transferred and preserved your original media and made personal viewing copies, you’ll want to organize and share your memories with your friends and family. Visual-database programs such as Extensis Portfolio <www.extensis.com/portfolio> and ThumbsPlus <www.cerious.com/thumbnails.shtml> can help you view, categorize and sort digital copies of audio and video. These programs enable you to label files by keywords (such as Grandpa Joe and Mom) and data fields (such as file type and date), so you can easily access what you need. With these programs, you’ll be saving your memories on your computer’s hard drive. Computer memory is relatively inexpensive — for around $100, you can buy enough memory to store several hours of audio and video. In addition to saving your files on a hard drive, archivists suggest you copy them to a DVD, and store at least one copy in an alternate location — a safety-deposit box or another relative’s home, for example — to prevent loss from computer crashes or natural disasters. Make as many copies as you like of the digital files, or use a program such as Apple’s QuickTime Pro <www.apple.com/quicktime> to embed video or audio in a Web site that anyone can visit.

If you’re too busy to take on such a big project, or if it’s all too technical for your taste, you have other options. EZArchive <www.ezarchive.com/zbox/app/home> helps consumers manage their personal photo, video, film, audio and text files online. The company partners with handlers across the country to do everything from restoration to transfer to digitization, and then loads it all onto a password-protected, searchable Web site. The same backup security measures that protect banks and large corporations make your memories less vulnerable to hard drive crashes and system failures. While this kind of service and security isn’t cheap — prices are competitive in terms of scanning and digitization, and there’s a monthly fee (based on storage size) to host your archive — some people prefer to leave everything to the experts. After all, even one mistake can erase the past forever.

Family Drama

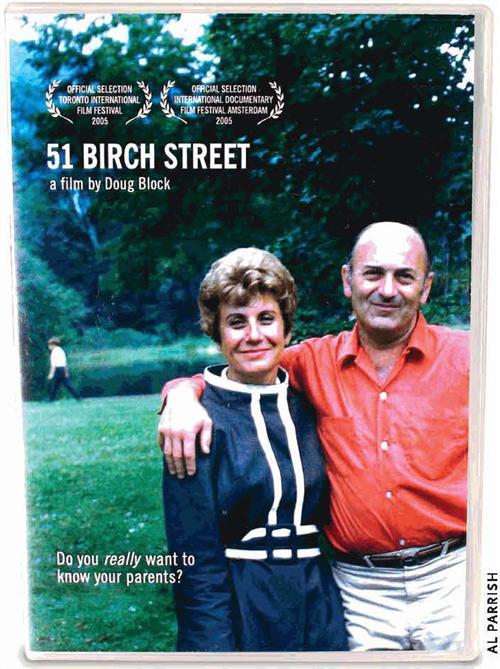

Every family — even a seemingly ordinary one — has a story. Filmmaker Doug Block thought his clan was pretty typical. But a few months after his mom died, his father married a former secretary and announced he was moving to Florida. As Block began recording interviews with his dad and helping pack up his childhood home, startling revelations came to light about his parents’ marriage. In the engrossing documentary 51 Birch Street <www.51birchstreet.com>, Block tells his family’s tale by weaving interviews spanning several decades with faded snapshots, 8 mm home movies and passages from his mother’s diaries. (See the Web site for screening dates and locations.) We asked him for some simple secrets to capturing family stories — both ordinary and extraordinary — on film.

Family Tree Magazine (FTM):

You had a goal when filming 51 Birch Street: to figure out the complexities of your parents’ marriage. Should anyone who’s doing an interview have a goal?

Doug Block (DB):No, not necessarily. I had already interviewed my mother and father with these family history interviews I had done no years ago, and I had no intention of them being in a film. It was strictly for me and my sisters and our children to have. I highly recommend everybody do one. It’s easy, and I can’t think of anything I’ve done that gave me a better understanding of what my family was all about and brought me closer to my parents.

FTM:How did you conduct those interviews?

DB: It was very conversational. You come armed with a list of questions and allow a conversation to grow out of that — but keep referring back to the questions. The first thing I would do is take out an album of family photographs and look over it with my parents and ask them who these people are. It brought them into the past and set the stage for the interview.

Generally what happens is I ask a question, and my subject will go on for two or three minutes. I don’t usually have to ask a lot of questions. It’s in the follow-up questions where you get factual details: “Where was the apartment? In Brooklyn — is that where Grandma lived?”

FTM:Interviewing people is your job. How do you know what questions to ask?

DB: I would just start at the beginning and take it chronologically. It’s simple and probably easiest for the person you’re interviewing. I usually start by asking something like “What’s your earliest memory?” or “Do you remember your grandparents?” “What was your childhood like?” I always find it really interesting how the family came over from America, so I would touch on that.

My father’s father died when he was pretty young, and I knew nothing about it, so I asked my dad what that was like. It was astonishing the detail he could recall. It was the ’70s when we talked about it, and he could lay such a visual of that day. You could practically smell it.

FTM:The people you interviewed in 51 Birch Street seemed so at ease. How did you make them comfortable?

DB: People tend to be at ease if you’re at ease. That’s why I recommend setting up the camera on a tripod, then leaving it alone. Make sure the camera’s rolling and don’t even give it a second thought. I like to put the person near a window so the light is falling on their face. Frame the shot fairly close. A common mistake is to leave the camera angle too wide — you watch the tape and feel like you’re a million miles away. You want to see the emotion. I’d recommend framing the person’s face just off the top of the head and maybe down to the collarbone or top of the chest. It’s not so close it’s suffocating, and it lets the person shift slightly without going out of the frame.

Some subjects have a hard time focusing on the camera and their eyes constantly go back and forth between the lens and you. That’s not good — it should be one or the other. If people are comfortable talking to the lens, that’s my preference, because when you play the tape it looks like the person is talking to you. But if they want to look at me during the interview, I’d put my face behind the camera as close to the lens as possible.

FTM:Some clips in the film show your parents together. Is there a trick to working with two subjects?

DB: Usually in a double interview most people zoom in on whoever’s talking. But I find it interesting to get the two of them together, to see what their body language does and how they listen to each other. In my family, there’s a lot of back and forth, so it was interesting to have a wide angle that included both of my parents.

I’d say mix it up if you can: Do some single shots, some shots of both people, some zooming if you’re up to it. But for most people, it’s hard enough to concentrate on the interview, and that’s why they tend to lock off the camera. In that case, I’d keep it a wide angle on the two of them.

FTM:What do you do if a subject just doesn’t want to open up?

DB: You can only press people so far if they’re unwilling to go somewhere. I tend to move on to other questions, and then try to come back to the one they’re avoiding and rephrase it somehow. In the film, I tried every which way to get my father to admit he’d had an affair without actually asking. I used every euphemism I could. He finally did answer no.

FTM:But some information, such as what your mom wrote in her diaries, could be hard for an interviewer to take. How were you dealing with all this?

DB: I think making the film was my attempt to come to grips with what I was learning, to put it in a form I could deal with. It was helpful to know that telling the story of my family would help other families. I kept thinking people will come out of the movie theater and feel this urge to call their parents.

I don’t think most people do family trees or family history interviews until they feel a desire to know their parents or connect with their history. So I think it comes at a point when you’re ready to find out stuff that might not be wonderful, or in keeping with the image you had of your family. There might be things that are painful to learn, but I’ve never empathized more with my parents than when I started doing this film. It humanizes them and makes me feel more connected to them. The rewards so far outweigh anything negative you could find out. My father was so happy that I was interested and listening.

FTM:That reminds me of what your mom’s friend Natasha said in the film: “What a relief for someone to really know us.” It’s something to remember when planning an interview.

DB: I think so. Everybody wants to be understood, and you particularly want to be known to your family. Just because you ask a question doesn’t mean they have to answer it. It’s important at the beginning of an interview to say, “If there’s anything you don’t want to talk about, please tell me.” Remind the person this isn’t going out on the nightly news, either — it’s really for the personal use of the family. When I decided to make the film, after I’d already done several interviews, I had every family member sign a release form.

FTM:Should everyone do that before an oral history interview?

DB: No. No, you don’t have to do it until you feel you’re going to broadcast it or sell the footage or something. You can always go back and have someone sign a form. I wouldn’t do it for a typical interview. The more you can make it seem like it’s not a big deal, the better.

FTM:Most Family Tree Magazine readers probably won’t make a movie. What’s the minimum they should do to the raw footage?

DB: The easiest thing is to digitize it into a computer editing system. There are some very simple ones, like iMovie <www.apple.com/ilife/imovie>. The price of hard drive space has come way down, something like $100 for 100GB. That would hold about five hours of video. I’d shoot some photographs to illustrate what the subject says. What a lot of people do now is scan photos and do computerized camera moves, simple zooms and pans.

FTM:How have people reacted to 57 Birch Street?

DB: I’ve never had a film where the reaction has been this intense and emotional. It’s striking a deep chord in so many people for so many reasons. People tell me family stories that make mine look ordinary.

Part of our Web site is now devoted to people’s stories of their attempts to connect with their parents — their breakthroughs and how they did it. We have tips on how to get to know your parents. One way is interview them. Make a video, do an oral history, do a family tree. My hope is that the outcome I got inspires people. It can hurt, it’s not always easy or comfortable, but now I have a relationship with my father where I didn’t have one before. It’s like night and day.

Even when properly preserved, no memory medium lasts forever. Here are the shelf lives of various formats:

• Film: Upward of 100 years. Film is considered one of the most stable media. People have been recording stories on it for more than a century, and some early motion pictures still exist today. Sadly, according to the Library of Congress, many films have been lost because they weren’t properly cared for.

• Magnetic tape: 10 to 30 years. Chemical degradation and biological hazards are the biggest culprits in the failure of magnetic tape over time.

ADVERTISEMENT