A WWI service member from Pennsylvania was later named Chief Yeoman of the US Navy. A British ambulance service volunteer became a sergeant in the Serbian Army. An American journalist was awarded the Legion of Honor by the French government. If you heard the stories of these individuals who served and sacrificed during World War I, you may assume you’re looking at the résumés of men. But the experiences of Loretta Perfectus Walsh, Flora Sandes and Mildred Aldrich represent the countless contributions women made during this pivotal time in history.

The Great War mobilized women on all sides in unprecedented numbers from 1914 to 1918. While the vast majority of those women were drafted into the civilian workforce to replace conscripted men or staff expanded munitions factories, thousands also served in the military as nurses and in other support roles. In Russia, some women actually saw combat, including a peasant named Maria Bochkareva, who secured the personal permission of Tsar Nicholas II to join the Imperial Russian Army. She led the “Women’s Battalion of Death” combat unit.

“[Women] not only gained the gratitude of many in their own generation but they proved, for the first time on a global scale, the enormous value of a woman’s contribution, paving the way for future generations of women to do the same,” writes Kathryn J. Atwood, the author of Women Heroes of World War I: 16 Remarkable Resisters, Soldiers, Spies and Medics (Chicago Review Press).

Whether your female ancestors served in the trenches, tended to the wounded, worked in a factory or participated in conservation or patriotic efforts back home, here’s where to find key resources for tracing your female ancestors and learning about their contributions during World War I.

Women on the battlefield

In 1917, more than 20,000 American women joined the US Army Nurse Corps. More than half of these sailed overseas, leaving their families and private jobs to work under hazardous conditions as nurses to more than a million battle-wounded and ill American soldiers. Look for these clues to the service of women in your family:

US military service records

Just as for male soldiers, records are available for women in branches of the service. Although a 1973 fire at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis affected more than 16 million files of Army and Air Force personnel discharged in 1912 and later, you still might find records for female ancestors.

“Look for payroll records, morning reports and monthly personnel rosters, especially if service records no longer exist,” advises Jennifer Holik, a military historian and author of Stories of the Lost: Discovering the Story of Our Heroes Through Genealogy (Generations). “Also listen to oral histories and read unit histories or books about the branch of service in which your female ancestor served. These histories will provide context, even if your female is not named.”

To find women’s service records, start your search online. Subscription site Ancestry.com includes databases such as a roster of North Dakota men and women who served during World War I. Look for the site’s other WWI databases by using the Ancestry.com Card Catalog. You can search by keywords or filter by location, record type and year.

For example, a keyword search for nurse in the Card Catalog shows a database of American Red Cross nurse files from 1916 to 1959. Records in this database, which includes WWI records, provide the nurse’s name, residences, birth date and place, a list of assignments, education and licensing, professional experience, Red Cross badge number and more. A keyword search for women world war 1 returns a list of military records databases that contain information on both men and women who served from various US states.

In addition to Ancestry.com, check subscription site Fold3.com, which specializes in military records. To explore available WWI records on Fold3.com, click on the Search tab and select Browse Records. Next, select World War I from the Category list. The Connecticut World War I Service Rosters database, for example, has more than 66,000 records relating to the service of Connecticut men and women in the US Armed Forces (1917-1920).

UK service records

For UK ancestors, check FamilySearch.org, which has a few databases for UK WWI records, including a collection of UK Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) records. This collection, which you can browse but not yet search by name, contains records of 7,000 women who joined the WAAC between 1917 and 1920. These records, which are also available at the UK National Archives, contain enrollment forms, statements of service and other service documents. Another possibly useful WWI collection on FamilySearch.org is UK WWI service records (1914-1920). In addition, subscription site Findmypast has databases of UK military nurses from 1856 to 1994 and military nurses who earned the Royal Red Cross recognition.

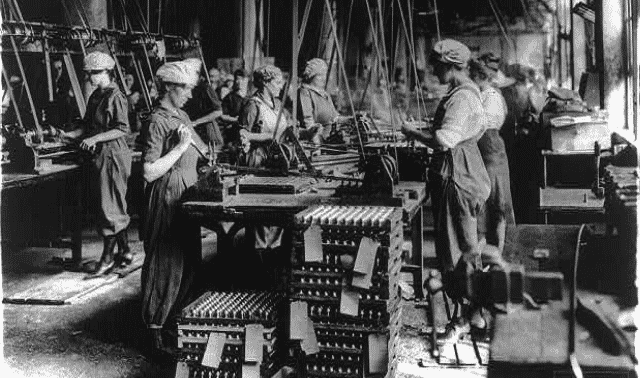

Women at work

While some women managed to enter traditionally male career paths prior to the First World War, for the most part women were expected to devote themselves to homemaking and “women’s work”—jobs in the textile manufacturing industry or clothing trades. Before 1914, women in only a few countries, including New Zealand, Australia and some Scandinavian nations, had earned the right to vote. In WWI America, suffragists advocated for the right to vote (finally received Aug. 18, 1920), but women were otherwise minimally involved in the political process.

The Great War helped change that. Rosie the Riveter helped make female industrial workers famous during World War II, but women also were active in factory and farm work during the First World War. Industrial production was critical to the war effort, and severe labor shortages emerged. Women were called on, by necessity, to do work and take on roles that were outside their traditional gender expectations. A 1917 poster by the National Industrial Conservation Movement stated the case for putting women to work:

It takes the best co-operative efforts of from six to 20 workers at home to properly equip and maintain one American soldier at the front. […] With consistent help and encouragement for their wage-earning partners and themselves, from all classes of the people, American industry can and will win this war for human liberty. Breeders of industrial war at home must be eliminated. National co-operation is the slogan to insure victory for Democracy over Autocracy.

This was termed “dilution” in Great Britain, a process trade unions, particularly in the engineering and shipbuilding industries, protested. There, upward of 1.6 million women joined the workforce between 1914 and 1918 in government, public transport, munitions factories and elsewhere, but lost those jobs once the war ended. In America, the War Industries Board promoted increased industry efforts. Across the Atlantic, American women also took traditionally male jobs in unprecedented numbers. Female laborers usually earned less than their male counterparts and were expected to leave their jobs after the war.

Learn more about women at work during World War I in books such as those listed in the box above. Internet Archive has free digital access to works such as When Johnny Comes Marching Home by Mildred Aldrich.

Women on the home front

In addition to working in factories and on farms, women on the home front were volunteers and patriotic supporters of the country’s economic initiatives and conservation efforts. For example, war bonds and stamps were sold to provide war funds, and food rationing, scrap drives and salvage collections helped conserve resources. Propaganda posters showed women wearing stars and stripes and holding vegetables to promote the victory gardens families planted to reduce demand on the nation’s food supply.

Women signed up for the Red Cross and other organizations, knitted socks, sewed bandages and collected books in support of the troops abroad. One Red Cross poster showed a basket of yarn and knitting needles with the slogan “Our boys need sox. Knit your bit.” War songs, movies, rallies, victory concerts, v-mail, buttons, medals, memorials and monuments also encouraged patriotism.

These programs resulted in ephemera, personal papers and newspaper articles about women’s war efforts. Search for diaries, manuscripts, photos, newspapers and recordings in the Library of Congress American Memory collections on Women’s History and Military History. Discovering Women’s History Online also offers news clippings, biographical sketches and more.

View photos of women’s war efforts on the National Women’s History Museum website and on Pinterest boards such as Women at WAR … Home Front.

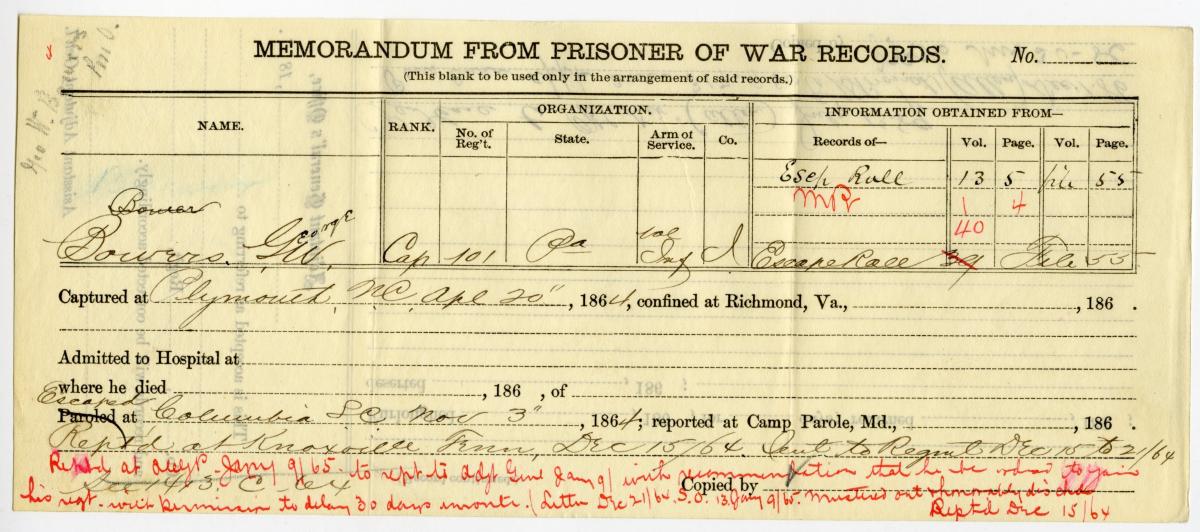

Widows and war brides

With an estimated 16 million deaths and 21 million wounded, World War I ranks among the deadliest conflicts in human history. Countless women and children were left behind. Researching the veterans who served can lead you to records that name widows or other family members. For information on requesting US service records and pensions, visit the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) website. For Canadian resources, go to Library and Archives of Canada website; see the UK National Archives for UK records.

Online WWI databases, such as Ancestry.com’s, might name women. In particular, search the WWI draft registration cards database (also available on the free FamilySearch.org). Once you find your male relative’s registration card, look for a wife or mother’s name listed as a relative. Soldiers female relatives might be named in these resources, too:

Gold Star mothers

In the late 1920s, the US War Department would assist mothers whose sons were buried overseas in making pilgrimages to their sons’ gravesites. The War Department’s Nov. 15, 1929, list of 11,000 women entitled to make the pilgrimage are on Ancestry.com. Each record provides the name of the widow or mother, city and state of residence, and relationship to the deceased, along with the decedent’s name, rank, unit and cemetery. Due to spelling errors in the original documents, the woman’s and decedent’s surnames may be different in a few cases. For additional resources, read NARA’s WWI Gold Star Mothers Pilgrimages articles.

War brides

During World War I, US citizenship laws allowed foreign-born wives to become American citizens by marriage. In 1919, the New York Times reported that at least 10,000 WWI soldiers had married in Europe. “War brides” and their children could move to the United States once the newlyweds completed the required paperwork to secure the bride’s government-sponsored transport to America. The brides often stayed in “bridal camps” while they waited.

Search passenger manifests for Ellis Island and other ports in the years following World War I for American men returning with foreign-born wives. Manifests are on Ancestry.com; some are at the free FamilySearch.org. In addition, before moving to the United States, war brides received emergency passports valid for six months. Search passport applications (1795-1925) on Ancestry.com; NARA has them on microfilm.

Professional genealogist Kathleen Brand also recommends looking for correspondence and other information in an unindexed NARA collection titled War Brides—General, covering 1917 to 1934. It’s located at the NARA facility in College Park, Md. See Brandt’s other recommended war bride resources at Archives.com under the Learn tab.

As many as 35,000 Canadian soldiers married British women. The blogs Canadian War Brides of the First World War and Canadian War Brides of World War One have links to information and passenger lists. Also see and the Canadian War Brides page on Facebook.

Wills

A will may mention the soldier’s wife or other heirs. US soldiers headed to war may have filed wills with county probate courts. Look for digitized county records on FamilySearch.org and on FamilySearch microfilm; a local genealogical society may have published an index to wills. Subscription website findmypast.com has a searchable database of transcribed WWI Irish soldiers’ wills. In 2013, more than 230,000 British soldiers’ wills and letters from World War I were digitized and made searchable at UK government archives (there’s a fee to view the record).

As Edith Cavell, the British nurse who was executed for helping Allied soldiers escape from German-occupied Belgium, said, “I can’t stop while there are lives to be saved.” Follow her inspiration and don’t stop chasing the stories of the brave women in your family history.

Women in World War I Resources

Websites

- 12 Resources for Researching WWI Overseas Marriages

- American Red Cross History

- Cyndi’s List: World War I

- First World War

- Heroic Measures: American Nurses in World War I

- Marine Corp Women’s Reserve

- National Women’s History Project

- The Role of Women in World War I

- US Army Women’s Museum

- Women’s Army Corp Veterans’ Association

- Women in the Armed Forces Bibliography

- Women in Military Service for American Memorial

- Women in the US Army

- Women in the US Coast Guard

- Women in War Time (Australia)

- Women Mail Carriers

- The World War I Historical Association

- WW1 Military Service Records

Books

- American Women and the U.S. Armed Forces: A Guide to the Records of Military Agencies in the National Archives Relating to American Women, compiled by Charlotte Palmer Seeley, revised by Virginia C. Purdy and Robert Gruber (National Archives and Records Administration)

- Heroic Measures by Jo-Ann Power (The Wild Rose Press)

- How to Locate Anyone Who Is or Has Been in the Military, 8th ed., by Richard S Johnson (Military Information Enterprises)

- War Brides: The Stories of the Women Who Left Everything Behind to Follow the Men They Loved by Melynda Jarratt (Dundurn Press)

- Women Heroes of World War I: 16 Remarkable Resisters, Soldiers, Spies and Medics by Kathryn J. Atwood (Chicago Review Press) • Women, War, and Work: The Impact of World War I on Women Workers in the United States by Maurine Weiner Greenwald (Praeger)

Tip: Learn about the accomplishments of Flora Sandes and other notable women of World War I at FirstWorldWar.com.

A version of this article appeared in the July/August 2014 issue of Family Tree Magazine.