Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

National census records naming UK residents, created every 10 years starting in 1841, give you a regular snapshot of your relatives in the United Kingdom. They place an individual or family in a location on a specific date, and can provide information such as names, relationships, place of birth, marital status and occupation. As for US censuses, the details recorded about each person increased over the years.

The good news is that images of census records for 1841 to 1921 are readily available online. These cover England, Wales, and the Crown dependencies of the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man. (The UK countries of Scotland and Northern Ireland participated in the censuses as well, but those countries’ records aren’t always in the same databases as English records, so we won’t cover them here.)

We’ll share when and how censuses were taken, their availability online, and some search strategies to help you find and understand the data on the images.

ADVERTISEMENT

A History of UK Censuses

The United Kingdom has taken a census has every 10 years since 1801, with the exception of 1941, when World War II kept the government preoccupied. (The 1931 census also was destroyed during the war.) The House of Commons passed an act in December 1800 to organize the census, and the first census in England and Wales was taken the night of March 10, 1801.

Parliament continued to enact legislation every 10 years from 1810 to 1910 to allow each census to be taken the next year. The Census Act of 1920 eliminated the decennial legislative requirement and provided for an enumeration at any time, so long as five years had elapsed since the last census.

The 1801 through 1831 censuses were conducted at the county level; the national government didn’t collect the returns. Overseers of the Poor, clergy, and other local officials served as enumerators. These censuses requested only the name of the householder, the number of families in the dwelling, and the numbers of males and females in the household. The records are therefore of limited genealogical value and in any case, most of the documents were lost or destroyed. Local county records offices may have some surviving pieces; some have been transcribed and published in books such as Pre-1841 Censuses & Population Listings in the British Isles by Colin R. Chapman (Genealogical Publishing).

ADVERTISEMENT

The 1841 census was the first “modern” enumeration, organized and collected centrally under the office of the Registrar General. For the first time, the original materials were kept and stored. It also was the first census to list the names of every individual in each household or institution. The only information requested was name, age, gender, occupation, whether born in the parish where currently enumerated, or whether born in Scotland, Ireland or “foreign parts.”

When UK Censuses Were Taken

It’s important to note the date an enumeration was conducted and how the information was gathered and processed. Enumerators were responsible for distributing census questionnaires before the official census date to every inhabited dwelling and institution.

Instructions printed on the form helped the householder understand whom to include and how to enter the information. The householder was to complete the form and name every individual who would spend the night in that place, including travelers. People who were working or traveling during that night were supposed to be included on the schedule at the house where they usually returned in the morning or at the place where they would’ve stopped on that night. But some night workers and travelers were inevitably omitted because of confusion over the instructions.

The census was to be completed based on occupancy on the nights of the enumeration dates listed above. By comparing the age of a person from one census to the next, and taking into consideration the official census date, you may be able to note that a person’s birth date falls between, for example, March 30 (the 1851 census) and June 6 (the 1841 census).

Immediately following census night, the enumerator revisited each dwelling to collect the completed forms. This might require multiple trips if no one was home. The enumerator also might help householders who were illiterate or who didn’t understand the instructions to complete the questionnaire.

The enumerator arranged the collected forms in sequence for the district and copied the information into bound household enumeration books. Special enumeration books were prepared for hospitals, barracks, workhouses, orphanages, jails, prisons and other institutions. Beginning in 1851, special schedules covered sailing vessels.

It is these enumeration books that have been microfilmed, and later digitized, and whose images we consult today. The original 1841 through 1901 household books are deposited with the British national archives (TNA) in Kew, Richmond, Surrey, as are the 1911 and 1921 household forms.

Reading enumerator instructions can help you better understand records. In 1841, for example, enumerators were supposed to round the ages of those 15 years and older down to the nearest five years. Directions for one age group, for instance, stated “For persons aged … 35 years and under 40 write 35.” The exact age was to be recorded for those younger than 15.

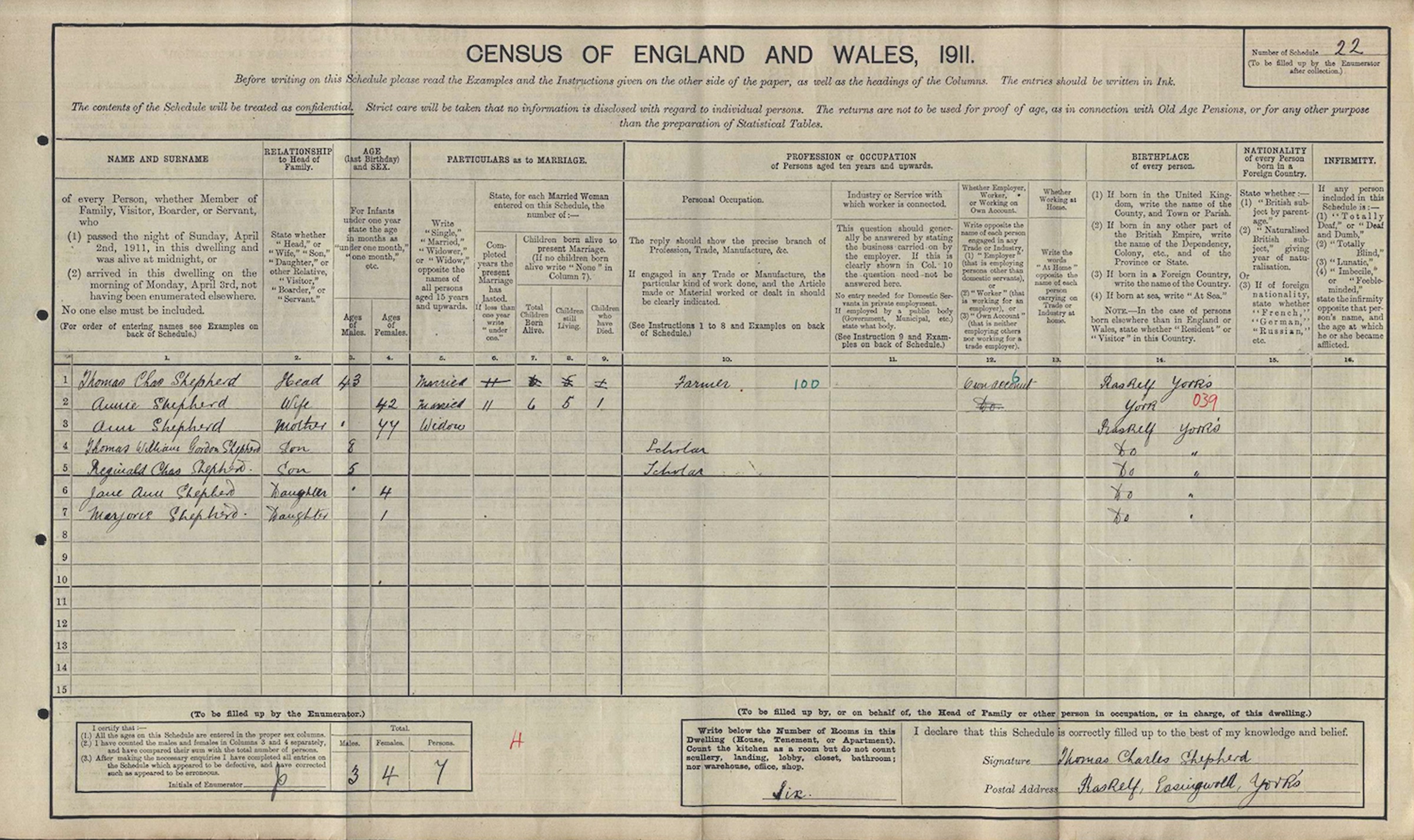

Household schedules serve as the official records for the 1911 census; the enumerators didn’t copy the forms into household books that year. Instead, they created summary books listing every address, even unoccupied buildings, with the names of the heads-of-household and statistics. You can view these on Ancestry.com.

The 1911 census also was the first to name military personnel overseas, some 135,000 soldiers on 288 bases and 36,000 naval personnel on 147 Royal Navy ships. Soldiers not on base on the night of April 2, 1911, were listed on the census schedule and marked absent. If a soldier was on leave in the British Isles, the census form should state whether he was in England, Wales, Scotland or Ireland. Naval crew on shore leave on the night of the census won’t be listed on the ship’s census return, since the instructions specify including only those on board.

Tips for Searching UK Censuses

Because the 1801 through 1831 censuses were never collected centrally, they were never microfilmed. TNA holds (and has microfilmed) the 1841 through 1901 census books and the 1911 and 1921 household schedules. County record offices throughout the UK may also hold microfilm or microfiche copies of censuses for their respective areas.

Fortunately, you don’t have to fly overseas or order microfilm to find ancestors in these censuses. Digitized records are now on these familiar commercial genealogy websites, along with indexes you can search by name:

- Ancestry.com

- Findmypast (which offers exclusive digital access to the 1921 census)

- MyHeritage

- UK Census Online

- The free FamilySearch lets you search indexes for these censuses, but the site links you to Findmypast—where you’ll need a subscription—to see the record images.

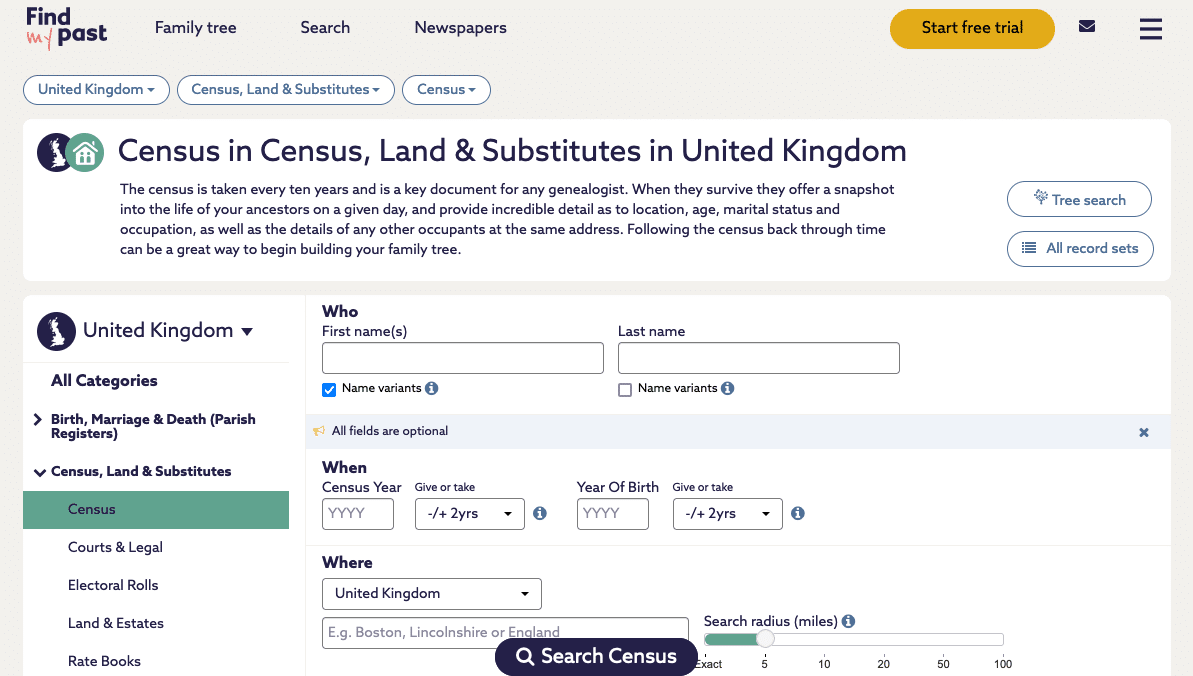

We’ll use Findmypast as an example. This site, based in the United Kingdom, provides comprehensive search facilities for UK censuses, along with complete online guidance to the content. If you don’t have a subscription, see if your library offers access or visit your nearest FamilySearch Center. Then follow one of these search strategies.

Search all censuses

If you’re hoping to find folks specifically in census records, skip the Findmypast home page search form because you’ll probably be overwhelmed with matching records of all types. Instead, click on the Search drop-down list at the top of the home page, then on the link for Census, Land & Substitutes. On that search form, under Where, narrow your search by selecting United Kingdom.

Next, look at the filters on the left side of your screen and click Census (under Census, Land & Substitutes). You’ll end up with the template to search for an individual in all the censuses.

You might start simply with the person’s name. You can select name variant check boxes for First Name and/or Last Name to find records with variant spellings, misspellings and initials. (The person who completed the form might have used nicknames, or a name might have been indexed incorrectly.)

The search results will include all matches to the name in all censuses and in all categories. You can select a census result, view a transcription of the record, or (if available) view the digital image of the actual census page. You can always go back to the search form to change or add information to narrow your search.

By adding the census year, you limit your query to only that census. Adding the year of birth, with a range of plus or minus 0 (exact), 1, 2 or 5 years, further narrows the resulting list of matches to those of an approximate age. Knowing the location also helps your search. Specify United Kingdom, then enter the name of the county. You could enter a more finite location, but remember that you might not get a match.

For example, I searched for Thomas Shepherd in Raskelf, Yorkshire, in the 1871 census, but there was no match. When I changed the location to just Yorkshire, I found him. The census page he’s on has the heading Raskelfe Civil Parish, the Village of Raskelfe, and the Diocese of York. But there’s an extra e on Raskelfe compared modern spellings of the place, and the 1871 census index includes it.

As you experiment with variations of your search terms, remember that adding more terms can increase the odds of not finding the person. Start broad, then add or change search terms one at a time. If your “target ancestor” has a common name, try searching for someone else in the family with a more unusual name. Instead of searching for John Alexander, you might look instead for his son, Ezekial Alexander, or his daughter, Parthenia Alexander. There’ll be far fewer Ezekials and Parthenias to review.

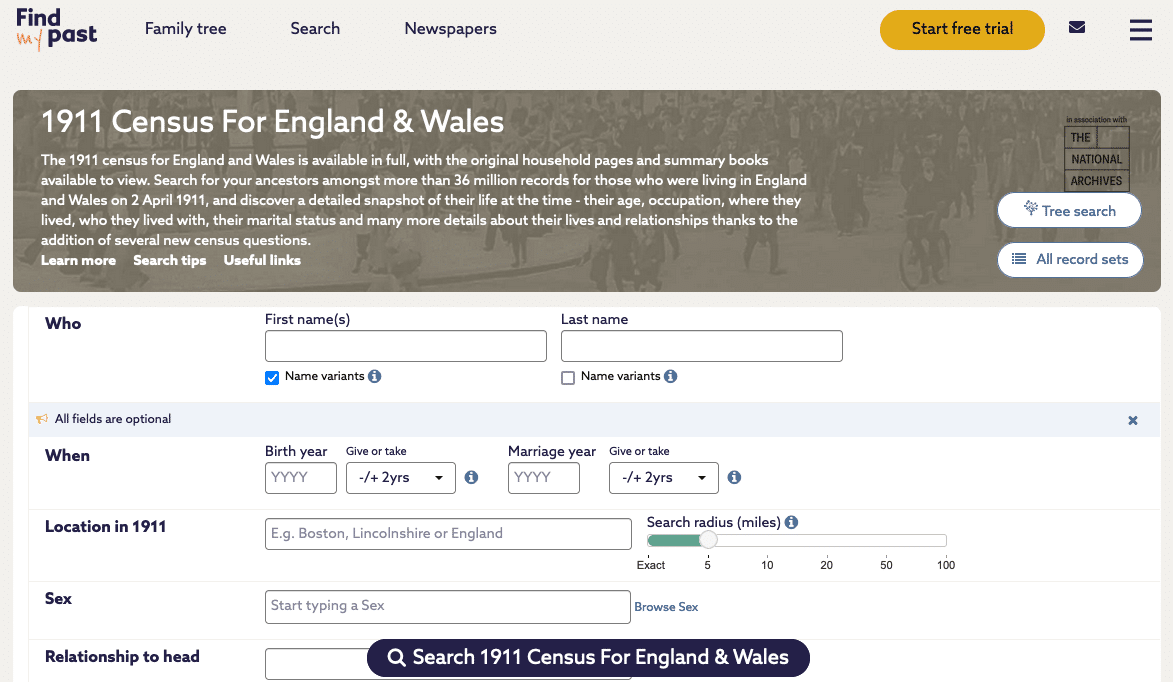

Narrow to a specific census

To search a specific year’s census records on Findmypast, click on the Search drop-down list at the top of the home page, then on the link for All Record Sets. On the next screen, under the Filter By box on the left side, click on Where > Britain (or specify England or Wales). Because the list sorts by number of records by default, censuses are displayed near the top. The site has separate entries for each of the 1841 to 1901 censuses (labeled “England, Wales & Scotland”) and the 1911 and 1921 censuses (“England & Wales”). Note that Findmypast provides only transcriptions for the Scotland censuses, but not digital images.

Click the link for a census to open its search form. Just as previously described, you can enter as much or as little information to facilitate your search. You’ll find census-specific information and search tips below the search form.

Browse by location

Examining all the census pages from one location might be helpful if you can’t find your relative where he should be. Try to narrow the place you need by identifying where the person lived in previous and subsequent censuses, as well as in other records covering the time period. Remember that enumeration districts changed from census to census. The GENUKI website has a tool to help you determine the civil registration district you need in England from 1837 to present, and in Wales between 1837 and 1996. These same districts were used to compile the decennial censuses from the years 1851 to 1911.

Start browsing by following the steps above to search one census. On the search form, enter the place as the residence (you can leave the name blank). Click on a search result, view the page image and use the arrows to page through the records.

Finding More Details in UK Censuses

Each UK census database offers its own search options and indexes the records differently, so it’s worth searching another site when you can’t find an ancestor in the first one you try. Regardless of which website you use, read the available help and information about the census collections.

Here’s an example of how the site’s background information is important: Remember how the records for the 1911 census are the original forms each householder completed, not the household books that enumerators copied? If the householder wasn’t very literate, you can expect to find spelling errors, which were indexed in the online database as written. In addition, an individual’s hard-to-read penmanship may have led names to be indexed in unexpected ways.

Two columns of particular interest in the 1911 census might have clerks’ annotations of standardized key codes. Findmypast has lists of these codes, which can help you decipher the householder’s answer:

- Personal Occupation: Find a list of occupation key codes for column 10.

- Birthplace: In column 14, the respondent may have written the location in a nonstandard way, making it difficult to identify on a map. For example, York may have been written as York’s, or later, used as an abbreviation for Yorkshire. Birthplace key codes are listed at here.

UK censuses are invaluable for locating and reconstructing British families and determining exact places of birth. These clues can point you to other records, such as civil registrations, church records, land transactions, taxes, newspaper articles and more. They also can help you trace migrations, occupations and other details to extend your understanding of your ancestors’ lives.

A version of this article appeared in the March/April 2017 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated in April 2024 to reflect the release of the 1921 Census of England and Wales.

Related Reads

ADVERTISEMENT