Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

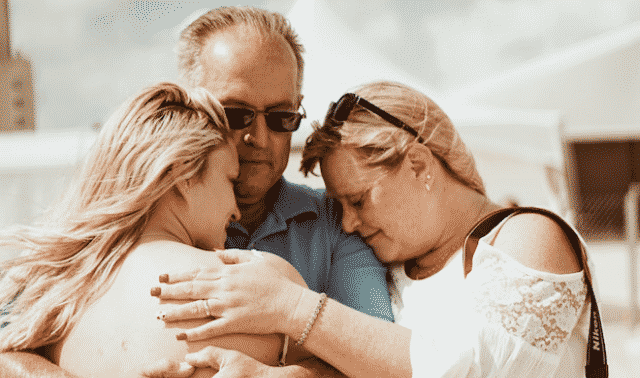

Two families meet: John Vanek (center) and his wife, Pamela Vanek (right front), along with their daughter, Eliza, and John’s parents Wes and Maureen Vanek (left), traveled to California to visit John’s biological father Bruce Olmscheid (center, back) and Bruce’s husband, Eric Lueck.

Three years ago, longtime genealogist John Vanek casually told his parents he planned to take a DNA test for family history. Within days—before he even took the test—his folks revealed startling news: He’d been conceived through sperm donation. Almost immediately, Vanek knew two things. First, his chances of identifying his birth father were slim. Second, he was going to try anyway.

And he succeeded—so well, in fact, that he started a genealogy research business specializing in tracing unknown parentage. But this story isn’t just his own. It also belongs to Vanek’s biological father, Bruce Olmscheid, who never expected to know the offspring conceived with his donated sperm. Their reunion has launched them and their families into uncharted relationship waters. Biology may define their past connection, but whether and how they share the future is entirely up to them.

Early interest

John Vanek was about 11 when he first encountered two subjects that would change his life: family history and DNA. Naturally curious about all types of science, he read a book about DNA replication. But a school family history project really captured his interest.

“I was asked to make a family tree and bring it to class,” he recalls. “I now realize that for me, the assignment was not about making a family tree, it was about talking to my grandparents. I think that’s the goal of these projects: to realize that people had lives before you came along.”

A gift of discovery

For Christmas that year, his parents gave him an early version of Family Tree Maker software. He started entering what his grandparents told him and adding to it as his research skills grew.

Vanek’s sixth-grade interests intersected again when, in 2015, his wife, Pam, gave him a DNA test for their third anniversary. “She knew I was deep into genealogy, and that I’d been watching as the various tests hit the market. I always knew the DNA technology would just get better and the price would keep coming down.”

The moment of truth

Vanek told his parents about the test during a trip to the Minnesota State Fair. “I can identify the exact moment they looked at each other and knew they needed to tell me the truth. They declined to go on the next ride with us, and I’m sure they discussed it.” By the end of the week, his parents came over for a sit-down with their only child.

“‘Don’t expect to find any Vanek cousins in your DNA matches,’ they told me. ‘You were conceived by sperm donation.’” Vanek’s life was set into motion by a live sperm donation at a fertility clinic, with the donor in one room and his parents in another. “My wife jokes with me, ‘You were conceived by turkey baster.’”

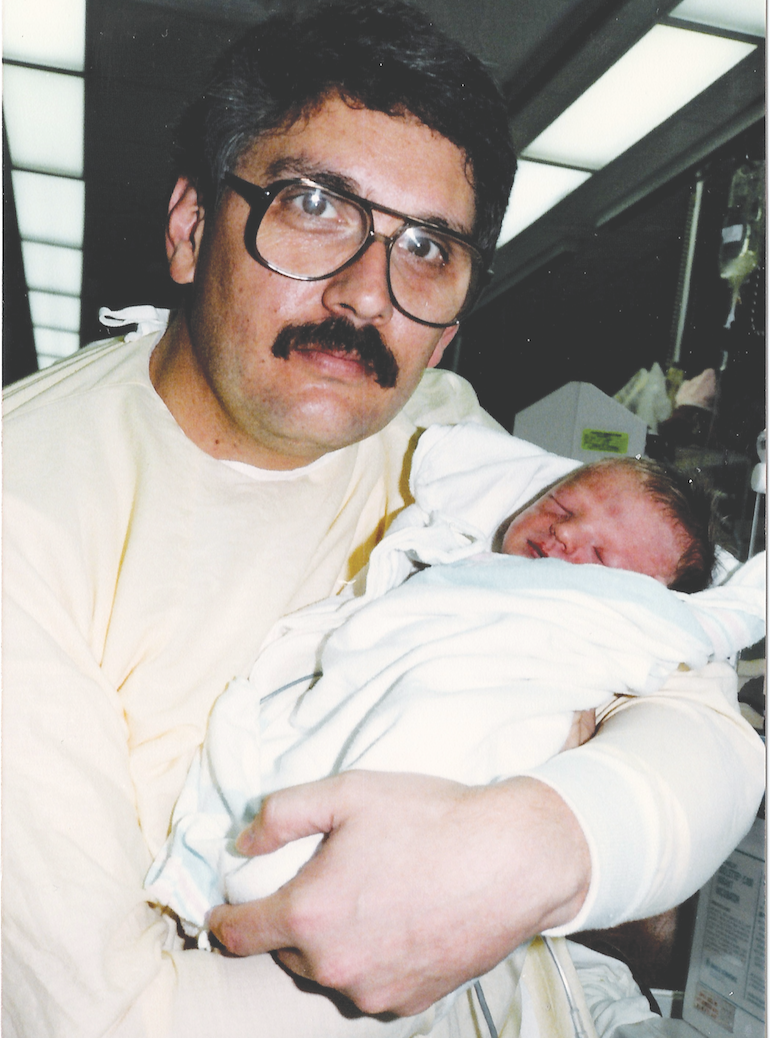

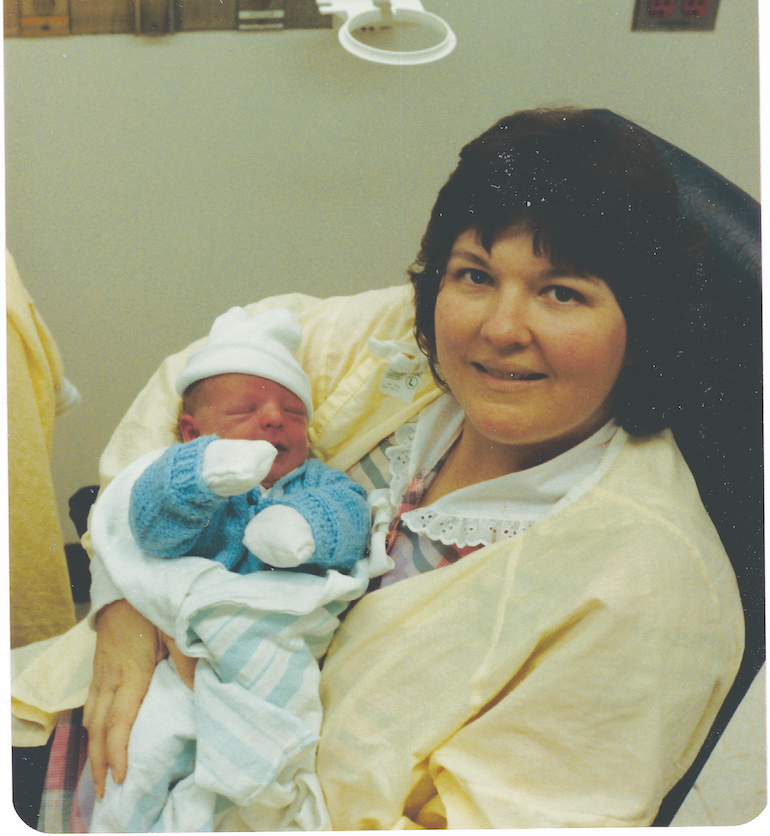

When John’s parents Maureen and Wes Vanek conceived their son through sperm donation, everyone expected the donation would remain a secret and the donor would stay anonymous.

Taking in the news

“The pieces fell into place about why I was an only child. I wasn’t upset then and I’m not now.” At the time, though, everyone involved expected that the donor would remain anonymous and the parents wouldn’t tell anyone. No one knew that 30 years later, genetic genealogy testing would make it possible to unravel the secret.

“They were told, ‘We’ll find you a match that’s similar enough to the father that it doesn’t raise any questions’” Vanek says. “My dad is 6 feet, 6 inches. I was always the tallest kid in class. It all fit.” His parents always found a reason not to tell him. “From their perspective, I totally get it: I’m their only child. There was a level of uncertainty about how I would react. It’s complicated to tell your kid after you’ve said nothing for so long.”

Vanek learns what he can

As he was still absorbing the news, Vanek asked what his parents knew about his biological father. They knew he’d try to identify the donor. But the live donation would make things difficult: no tracking number, no paper trail.

The nurse had shared a few details with Vanek’s parents. “He was about 6 feet, 3 inches, and of mostly German ancestry. He was musical and he was a medical student at the University of Minnesota.” Being a thorough genealogist, Vanek called the clinic to confirm the lack of records. The office had moved, the physician was gone and the 25-year retention policy for records had expired.

The research begins

So he pursued the slender clues in this trail of evidence. “Even before I got my DNA test back, I started looking through the University of Minnesota yearbooks and commencement programs,” Vanek admits. “But it’s a huge state university and it’s the Upper Midwest. Half the people who came here to school were German.”

As he moved ahead with his search, he had a couple of concerns. First, he didn’t want to upset his parents, with whom he is close. Candid talks with them helped calm those fears. The other question: What did he hope to accomplish if he found his biological father? This one wasn’t so easy to answer.

“I said I wanted to learn my medical history,” says Vanek. “And that was true, but to be honest, it wasn’t my primary motive. This was the most unexpected and unbelievable genealogical puzzle to have about myself and I needed to at least try to solve it.” He admits that until the time came, he never fully decided what he’d do if he found his biological father. It’s not an approach he recommends. “I think it’s important for people who are doing this to think about it ahead of time.”

When John’s parents Maureen and Wes Vanek conceived their son through sperm donation, everyone expected the donation would remain a secret and the donor would stay anonymous.

DNA search strategy

Vanek had ordered his autosomal test through AncestryDNA, and he asked his mother to test as well. He knew that the enormous pool of DNA profiles (now about 10 million) would increase the chance of finding helpful matches. He also knew he could set aside any matches shared with his mother; the remainder would presumably be related through his biological father. (This strategy would be more difficult for those whose parents are from an endogamous population, where individuals tend to marry within the group and thus share a lot of DNA.)

Before his test results were ready, Vanek outlined his research strategy. He planned to search the family trees of his genetic matches for German families in Minnesota. “I just had to hope my biological father was right about his ancestry. And then, if I could find two cousins who had a proven relationship, I would try to figure out at least roughly how I fit in. I later learned that this is called triangulation.”

The results are in

“When I first got my results back, I was really disappointed,” Vanek says. “I had only five cousin matches at the third-to-fourth cousin range, and four of them were on my mom’s side.” He had one third cousin DNA match on his biological father’s side. “She turned out to be about 102. Her grandniece administered her test. This was the only cousin match I ever contacted.” Later, as he discovered more matches, he’d study their linked family trees for information.

Those using genetic genealogy to trace unknown parentage generally identify ancestors who are common in matches’ trees, then trace the families forward in search of descendants who fit what little is known about the mystery parent. By comparing his 102-year-old cousin’s tree to another cousin who matched them both, Vanek was able to zero in on two couples born in Germany in the 1830s. “I was pretty confident that two of these four people were my direct ancestors, but I had no idea where they fit in my family tree. Between them, they had 124 grandchildren. Trying to come forward to the 1950s through that many lines was not going to happen.”

The wait for more cousins

As he extended the family trees of both couples, Vanek waited nearly a year for more cousin matches to surface. A breakthrough came not long after his daughter was born. “Another cousin [match] showed up with a single branch of Germans from the right county. As soon as I saw the surnames, I knew I’d solved the puzzle.” One name—Olmscheid—matched a man in the trees Vanek had built from those first two couples. “Helen Steffes was a granddaughter of one of the two target women, by the only child she had with her first husband. Helen married Paul Olmscheid.”

Paul and Helen were born around 1900, about right to be Vanek’s great-grandparents. He figured that if a son of theirs was his grandfather, he had a good shot at Olmscheid being his father’s surname. So he typed Dr. Olmscheid University of Minnesota into his web browser. “And there it was on the WebMD profile of Dr. Bruce Olmscheid: ‘Graduated from the University of Minnesota Medical School in 1987.’ It was surreal.” It was also sudden: Within 10 minutes of clicking on the new DNA cousin match, Vanek was looking at a picture of his biological father.

An important confirmation

Research in birth records and obituaries confirmed Bruce was a grandson of Paul and Helen. “It’s important to verify every step of your research,” says Vanek. “You don’t just start calling people by that name and saying, ‘I think you’re my dad.’ It’s not something to take lightly.”

As it turned out, Vanek isn’t actually a third cousin of his 102 year-old match. Rather, they’re first cousins, three times removed, with a half relationship because the cousin descends from the target ancestor’s subsequent marriage. But the genetic distance was accurate enough to point him to closer relatives.

Now what?

Vanek’s unsettled concern returned once he had his biological father’s name and contact information. “Having information and having a relationship are two separate things,” he says. “I already had a family and”—he’s only half-joking—“it’s hard enough now to get to all the family functions.”

He spent weeks drafting a nine-page letter. “I told him about myself and my background; I think I sent a picture. I let him know that I wasn’t after his money and didn’t need a father figure. I told him how I found him and who our ancestors were.” He shared his hope that Olmscheid would verify he’d been a sperm donor at that clinic and would share his family medical history. He didn’t ask to meet, or mention his baby daughter.

Vanek sent the letter to Olmscheid’s office. “I didn’t want to mess up his life and shock his family by sending it to his house. I included a cover letter in case someone else opened his mail.” He wanted to respect Olmscheid’s privacy—which Olmscheid later said he appreciated.

The man behind the donation

Olmscheid grew up in rural Minnesota with the dream of becoming a doctor. “In 1983, I started medical school after I got divorced and came out as a gay man,” he says. A flyer posted at the school asked for sperm donors for couples struggling with infertility.

“I needed the money. But also, I liked the idea that I could anonymously help someone have a family. Back then, gays didn’t have kids. I knew it would give me a lot of satisfaction to make a difference in the lives of a couple.”

One in a dozen

Vanek thinks he donated about a dozen times, but received no follow-up report on the success of the inseminations. “For years I joked with my friends, ‘What would I do if a kid ever found me?’ And then one day it happened.”

“I was in my office in Beverly Hills,” he recalls. “My husband, Eric, and I were leaving the next day for a two-week trip to the Holy Land. While finishing up all the last-minute details, I opened this thick envelope. The first paragraph said something like, ‘Hi, Dr. Olmscheid, My name is John Vanek, and I’m quite certain I’m your biological son. I just want you to know I exist and I want to thank you.’”

His initial reaction was joyful. “It worked! At least one of the times I donated was successful.” He read the letter privately at home before sharing it with Eric. They told their families via text.

Drafting a response

Olmscheid carried Vanek’s letter to Israel. He read it repeatedly, discussed it with Eric and spent several hours composing his response. “Essentially I said, ‘I’m really thankful you tracked me down. I’m happy to hear that your life is good, that you’ve brought such joy to your parents.’ I told him about my family and medical history. I was so happy to hear from him.”

The letter went off in early November and Olmscheid watched for an answer every day. But Vanek didn’t reply until after the New Year. He apologized for the delay, explaining that he hadn’t wanted to disrupt the holidays. “I really respected that,” Olmscheid says. “He didn’t want it to upset his family or mine.” They began emailing, and Olmscheid suggested a meeting. Vanek agreed and then revealed that he had a little daughter.

“I was even more thrilled!” Olmscheid says. “I told my brother and my friends and they immediately started calling me Grandpa.”

The first meeting

Olmscheid and Eric flew to Minnesota and met Vanek at a restaurant. The reunion went beautifully, inspiring an even bolder idea: On the spot, Olmscheid invited Vanek and the baby on a road trip to visit his grandmother—Vanek’s biological great-grandmother—who was just shy of 99 years old and still lived in Minnesota.

“It gave us 100 miles in the car together,” Olm-scheid recalls. “It felt surreal, as if I was watching us from a television camera. We talked about growing up and school and hobbies, and what it was like to learn about me. I was thinking, ‘Someday we’ll wish we had recorded this conversation.’”

Olmscheid and Eric returned to meet Vanek’s parents. The potentially anxiety-producing get-together went smoothly. “Though they never thought they’d be in that position,” Vanek says, “my parents were eager to thank the man who had helped them have a child.”

More family to meet

His great-grandma’s 101st birthday party gave Vanek’s family the opportunity to meet more Olmscheids. “My aunt said, ‘I’m so thrilled that you and Eric have your own family,’” Olmscheid recalls. “There’s nothing better than family.’”

Most recently, Vanek’s family flew to California to stay with Olmscheid and Eric for several days. “It was both wonderful and exhausting, especially with a 2½ year-old,” Olmscheid says. “It felt like a really long date. I wish we lived in Minnesota. It would be much easier to have this relationship develop if we could just pop over for Sunday dinner. But the time together also made this thing more real.”

John Vanek and his wife, Pam (center, with their parents on their wedding day in 2011), joke that John was conceived “by turkey baster.”

Charting a future

Not every birth parent search story is as happy as Vanek’s. He credits slow steps toward a relationship and setting realistic expectations. “The most challenging part has been figuring out what sort of relationship it is and how it affects the other relationships we already have,” Vanek says. “I’ve tried not to upset my parents, or to create jealousy, because that’s not what this is about. My parents have been nothing but supportive.”

His new bond with Bruce has only strengthened those existing relationships. “The whole thing has made me more aware of how important relationships are. Not only have I formed a new, positive relationship with Bruce, but it’s made me revisit the great relationship I have with my dad. I understand and appreciate him in a whole new way now.”

A new self view

At nearly 60, Olmscheid’s sense of self has changed. “I’ve always just been Bruce. Now I’m potentially—ok, I’m going to use the word—Bruce the father, the dad, the grandpa. It’s leading me to a place I didn’t anticipate I’d focus on at this time of life. I have a new sense of the trajectory of time, of getting older, of generations.” He values more time with his brothers and has forged new connections with a brother who has children.

Olmscheid acknowledges that the revelations genetic genealogy enables affect more than just the people directly involved. “What about our spouses?,” he asks. “I’m the one who’s feeling the excitement and creating a new relationship. I have the blood connection. It’s different for Eric. He’s protective of me and of us. Something like this affects a lot of people’s lives, not just mine and John’s.”

It’s Vanek’s daughter—and his newborn second child—who triggers Olmscheid’s deepest response. “I want to spend more time with her and I want to see her grow up. As far as I’m concerned, that little girl cannot have too many people loving her. Am I going someday to be ‘grandpa’ or will I always be ‘Bruce’ [to my biological grandchildren]? Every time I feel the excitement of ‘I’m a grandpa,’ I remind myself I’m really not. But I am. But I’m not. I’m not quite sure what my role or title is.”

The story continues

So for both men, the story is a work in progress. “I have a dad and I am not looking to replace him,” Vanek says. “Because of that, it’s been hard for me to create a new paternal relationship when it didn’t exist for the first 30 years of my life. Bruce and I get along well, and I’ve enjoyed every minute we’ve spent together. But is it a paternal relationship? No. At least not yet. However, my daughter is little. I think her relationship with Bruce and Eric can be something more.”

“I’ve learned to take it one day at a time and move it in a direction it feels like it should be that day,” says Olmscheid. “I can’t control what it will be in 10 years, but I hope … Eric and I can come into their lives in a way that doesn’t take away anything from what they already have.”

A version of this article appeared in the July/August 2018 issue of Family Tree Magazine.