How did I discover what became of my third-great-grandmother? It started with realizing she didn’t die when I thought she did—a good lesson in always questioning your assumptions.

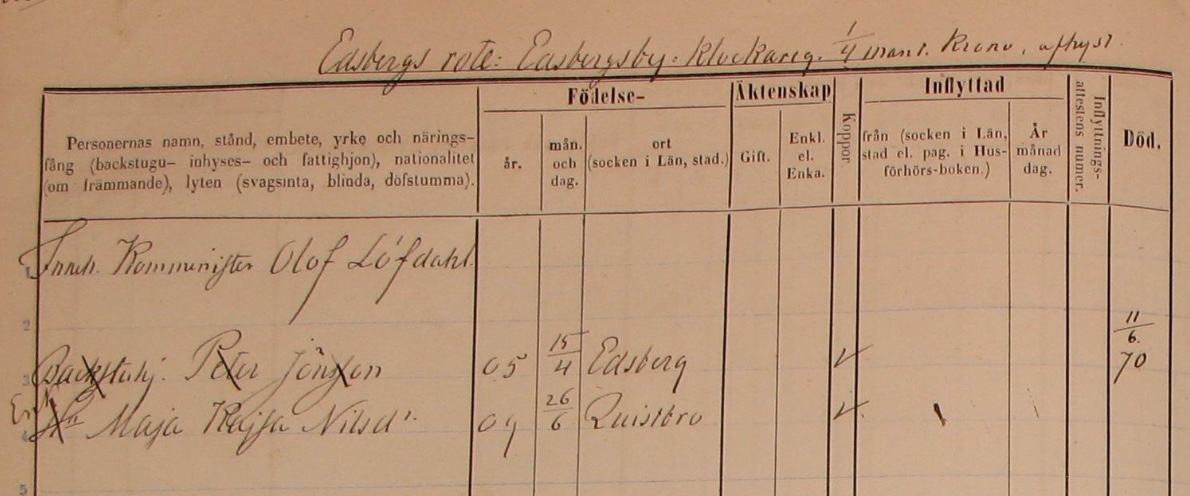

Maia Kaisa Nilsdotter, born in Sweden in 1809, married Peter Jönsson in 1832. Several years ago I found his 1870 estate inventory index entry, describing him as “widower.” So Maia must have died before her husband—a “fact” I dutifully noted in my tree.

Put the “re” in “research”

When I recently revisited that branch—another good genealogical practice—I couldn’t find Maia in Sweden’s well-preserved church death records. Weird. So I looked up her husband’s last entry in the church household examination books (much like an annual census) and, sure enough, his 1870 death was noted. Maia was listed below him, but without a death date—even though this page covered 1866 to 1870.

Maybe she wasn’t dead by 1870, after all. Sure enough, tracking down the actual estate inventory (rather than relying on transcriptions—another smart practice), it looked like the word was änka (widow), referring to her instead of him. Oops.

Missing Maia

But if Maia wasn’t dead, where was she? Searches in MyHeritage’s collection of Swedish household examination books failed to find her. Spelling variations of her name or birthplace might be to blame.

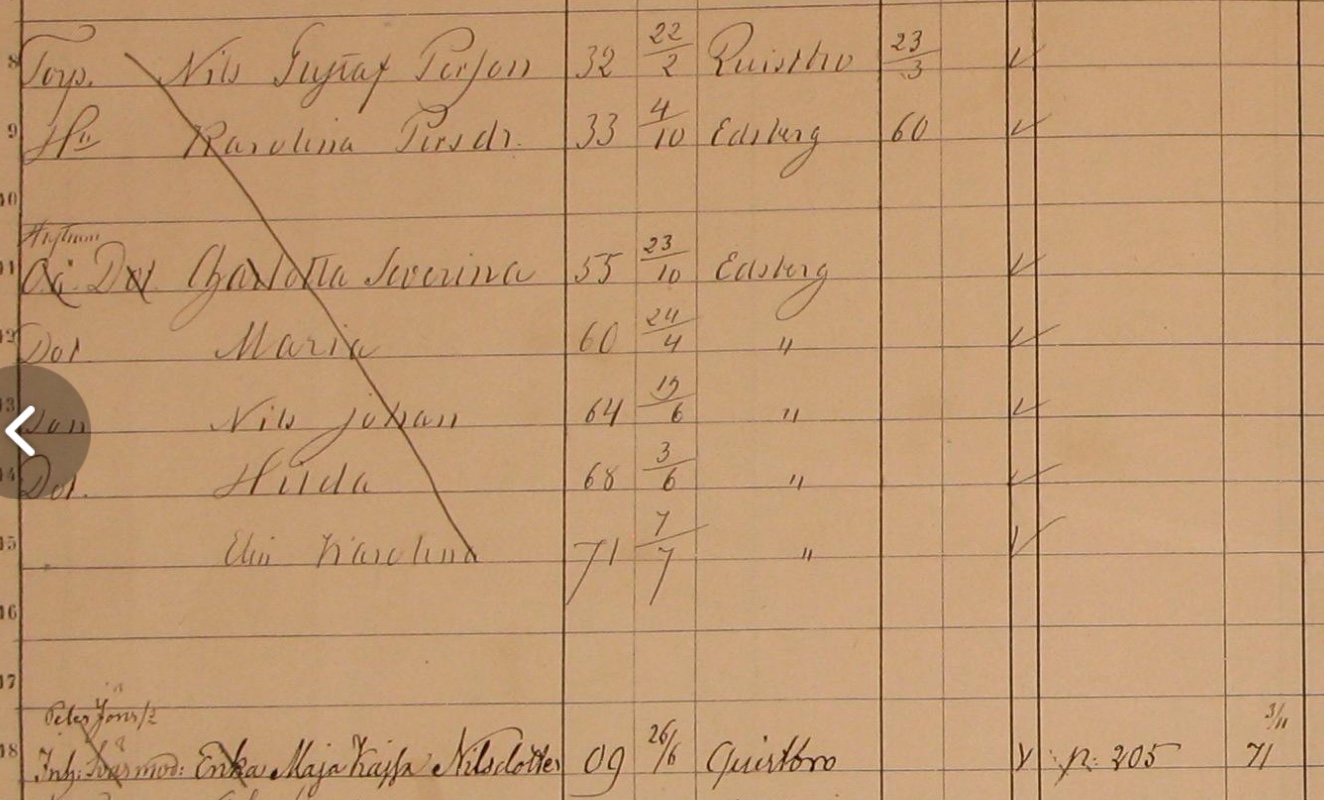

So I tried another go-to genealogy strategy: searching for relatives, in this case her children who’d stayed behind in Sweden (unlike my great-great-grandmother). I couldn’t find her son. Thanks to Sweden’s tradition of married women keeping their maiden names, however, I could search for her daughter, Karolina Persdotter.

I quickly found Karolina and her family in the book beginning with 1871. Scrolling down the page (always look at the whole page, and maybe the pages on either side), I spotted the missing Maia a few lines down, very much alive. In fact, as a quest for Karolina’s entries for the following years revealed, Maia didn’t die until June 19, 1887, living all the while near or with her daughter’s family.

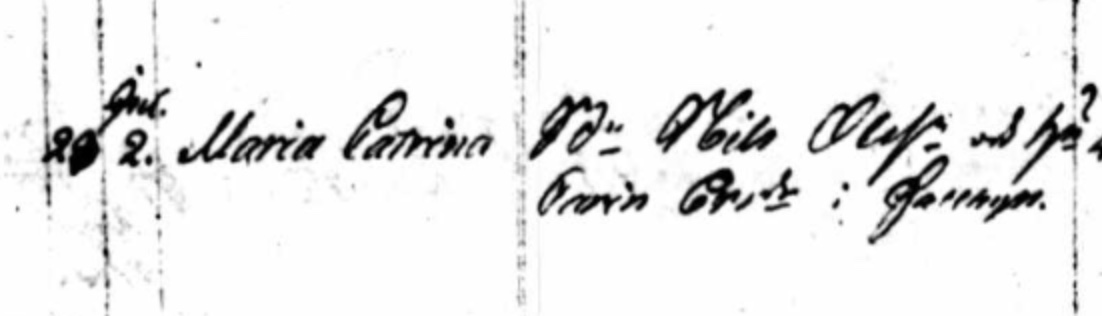

If questioning assumptions and revisiting sources could solve that mystery, what about Maia’s missing birth record? I’d previously noted a failure to find it in Kvistbro parish, where the household books said she was born on June 26 (“26/6”), 1809. I looked again and found a birth record on that date for “Maria Catrina,” daughter of Nils Olofsson and (illegible)—making her surname Nilsdotter.

FamilySearch has a helpful list of interchangeable Swedish first names “Maria” and “Maia,” it turns out, are interchangeable. Ditto for “Catrina” and “Kaisa.” So this was my ancestor, after all.

I now had her birth record and the correct date of her death, as well as her father’s name. Next I can start hunting for her mother’s hard-to-decipher name in other records. When I do, I’m going to question my assumptions and check everything twice.

Related Reads

A version of this article was first posted in November 2018. Last updated: July 2025