Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Tombstones have a long history. The word “cemetery” is Greek for “sleeping chamber,” and (appropriately) Ancient Greeks were among the first to designate land at the edge of their cities for burying the dead. By the time of medieval Europe, Christians wanted to be buried on consecrated ground either in a church or next to it. And before the Industrial Revolution, only the rich could afford markers and monuments.

More detail in tombstones means more value for family historians. But headstones are at risk due to their age and exposure to the elements, each causing them to deteriorate. It’s up to us “tombstone tourists” to understand exactly where we’re dealing with so we can document, repair and preserve these fragile monuments. Here’s what you need to know to enhance writing on tombstones and identify what kinds of repairs need made to them.

Evaluating a Gravestone

Before you do anything else, look around a gravesite to determine what condition the stone is in—including if the stone is too fragile to be repaired or cleaned. The stone may need nothing more than a gentle cleaning to remove grass and dirt, or you may find cracks, breakage and intricate damage that requires a more detailed plan to correct. Here are a few conditions to consider before deciding how to proceed.

Dirt, Debris and Vegetation

Cleaning a gravestone takes a cautious hand. Over time, soil, grass, lichens and ivy can take a toll especially on a marker that’s spent years embedded in dirt where grass has laid claim. But you’ll want to strike a balance between legibility, preservation, and historical accuracy (after all, the patina acquired over the years is part of tombstones’ charm). Our ancestor’s markers should retain their authentic look and appeal, and damaging practices and harsh products can weaken and destroy stones forever.

When cleaning a gravesite, trim away any excess grass, weeds, vining plants and saplings using scissors or sheers. Be careful when removing any plants by stem; their roots can affect the structure’s integrity and cause a marker to crack, fall or break apart.

If you’re planning to clean the actual tombstone yourself, pack a cemetery repair bag including water for washing and rinsing, a paintbrush for sweeping debris off the stone’s surface, and a toothbrush for cleaning dirt out tiny crevices. Another useful item is a plastic scraper to help lift off lichen and moss. But never use any metal tools or wire brushes, as they can scratch and create tiny fissures that let water and dirt into the stone, causing more damage.

Many gravestone and monument conservationists use D/2 Biological Solution mixed with water to clean certain types of gravestones, but this product may not be suitable for older or fragile tombstones. Also avoid bleach, household cleaners, shaving cream, commercial spray cleaners and anything containing acid. While first results may be a super white stone, the ingredients in these cleaners can eat away at the surface and leave a residue that makes it decay even faster.

Weathering

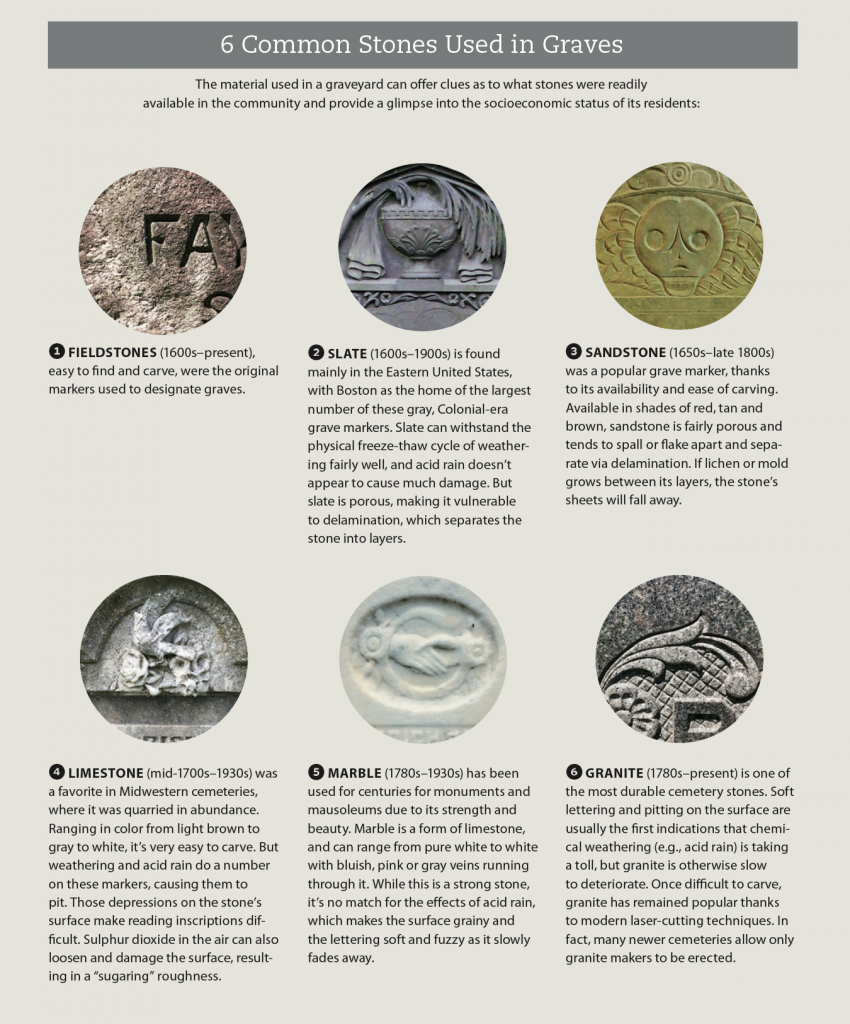

Weathering causes grave markers to weaken and wear down, and damage varies depending on the stone type (see the infographic below) and the marker’s location in the cemetery. There are three kinds of stone weathering that can occur: physical, chemical and biological.

Physical weathering happens during natural climate occurrences such as wind and precipitation. The direction a headstone faces can result in more or less weather damage. For example, a gravestone facing north (where some of the worst winter weather in the United States come from) will take the brunt of the elements and suffer more wear and tear than markers facing another direction.

Temperature changes can also lead to damage over time. Freeze-thaw weathering occurs when moisture trapped in a cemetery stone expands during freezing weather and contracts when temperatures rise above freezing. This “push-pull” effect can cause a grave marker to crack, break or fall apart. Freeze-thaw is especially damaging to sandstone and limestone markers.

Likewise, expansion-contraction weathering has the opposite affect with the same result. The outer stone surface expands during hot, dry days, then cools off rapidly at night. This creates stress on the marker that can lead to fissures and cracks, particularly in arid locations like the southwestern United States.

Chemical weathering, however, is caused by exposure to pollutants like acid rain. There are three different types:

- Carbonation happens when rainwater seeps into cracks or joints and weakens the stone by widening the gap. The marker then begins to erode on the surface, the lettering becomes blurry, and layers of the stone flake off.

- Hydrolysis is when acid rain reacts to certain minerals in the stone causing decomposition and pitting.

- Oxidation is when metal in a stone interacts with water and air, leaving stains or discoloration on the monument. (Think: The Statue of Liberty, made of copper, was once copper-colored).

- Biological weathering happens when living things like vines, lichens, moss and tree roots damage the structure and surface of the gravestone. They can even penetrate the stone, creating cracks separate into layers and eventually cause the marker to fall.

Minor Damage: Small Cracks, Chips or Breaks

Check for hairline cracks, chips and breaks. Inattentive lawn maintenance, storm damage, incorrect repairs (even by the well-intentioned), and—unfortunately—vandalism can take their toll on a cemetery stone. Elements like rain, snow and ice can create a freeze-thaw cycle that leads to small stress cracks that fill with moisture expanding the gap and leading to long-term problems.

If a tombstone is broken in two pieces (but is otherwise in good shape), you might be tempted to mend it with a special epoxy. But there are actually several points to consider. For example, where did the break occur? If the stone has broken at ground level, it will need a new base, complete with a socket to set the stone in. If the break is across the middle of the marker or runs diagonally, the ragged ends must be trimmed, and stone pins inserted before a stone-specific epoxy can be used.

Before taking on any repairs, talk to someone who understand stone restoration. What was once common practice might today be considered harmful. For example, broken stones were once “puddled” (set in cement) or bolted back together using stone plates. But today’s best practices call for less destructive methods that are also visually appealing.

Major Damage: Sinking Stones and Off-Base Monuments

Monuments sink depending on the type of stone, weight and ground beneath. You may have noticed older stones without bases that have sunk so far into the ground, making it so you can no longer read an inscription. (White bronze markers are notorious for this.) This fix requires a base be placed beneath the stone, which in turn requires the delicate task of physically removing the stone without placing too much force on it.

Monuments sinking into the ground (or totally knocked from their base) are best left for the pros. These repairs require specialized tools and equipment designated to lift fragile stones and keep them structurally intact while repairs are made.

Search for a conservation group that will preserve the stone and keep it accessible for years to come. There are numerous professional organizations and volunteer groups around the country that are trained and authorized in cemetery-conservation practices. A cemetery superintendent can assist in evaluating the gravesite situation and may be able to offer a list of preservation groups.

Enhancing Lettering on Stones

Over time, lettering and inscriptions can become difficult to read. At one time, gravestone rubbings with charcoal or chalk were recommended to capture what was written on the stone, but we now know even the most careful rubbings can cause hairline cracks, eventually causing a stone to break.

You can capture the clearest and most accurate record of a cemetery using a digital camera or smartphone, instead. Begin by photographing the marker at the front, then shoot the sides and back of the stone. And don’t forget to take photos of “the neighbors”; family members, friends, neighbors, workmates and fellow church members may have been buried nearby.

If the stone’s lettering is hard to see, use a flashlight or a mirror to direct bright light onto the inscription. Another option is filling a spray bottle with water and wetting the letters, so they stand out darker against the stone. Once you get home and upload your photos, you can convert the image to black-and-white and/or invert the colors using a photo-editing app to make letter stands out.

Preserving the Past

Cemeteries do more than simply provide a place for us to bury our dead. They stand as beautiful pieces of artwork and architecture in a gorgeous outdoor setting, and provide all kinds of information about our ancestors. From just the types and styles of tombstones, as well as their iconography, we can glean clues about our ancestors’ demographics and social class, plus glimpses of their community’s history, social values, cultural attitudes and religious beliefs.

When a cemetery is left to deteriorate or disappear, we lose valuable historical information about that community and its residents. This is why preserving cemetery stones and conserving our graveyards is so important. Whether you chose to focus on family graves or work to preserve local and regional graveyards, always remember the first rule of cemetery care: Do no harm. Your goal should be leaving that lasting cemetery legacy in a better condition than you found it.

As Benjamin Franklin once said, “You can judge the character of a town by the way their cemeteries look.” Do your best to help keep cemeteries and gravestones looking their best for future generations of tombstone tourists.

Related Reads

A version of this article appeared in the September/October 2021 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: June 2025