Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

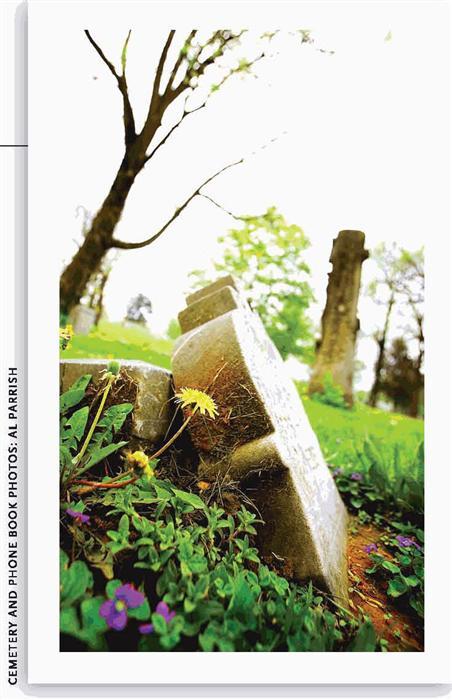

Old City Cemetery in Tallahassee, Fla., is the final resting place of plantation owners, slaves, yellow fever victims and Civil War soldiers. Established in 1829, this center-city graveyard has seen decades of both routine maintenance and extreme neglect. In the early 1990s, it fell victim to a particularly vicious act of vandalism. Headstones were overturned, ripped from the ground and shattered. The crime destroyed not only the sense of peace befitting a final resting place, but also the tombstones’ value as historical records and relics.

Fortunately, the Historic Tallahassee Preservation Board, along with the city and the Florida Department of State, fought back with restoration efforts including preserving stones and installing a fence. But most of our country’s tens of thousands of derelict or abandoned cemeteries remain all but forgotten, says Sharyn Thompson, director of the Florida-based Center for Historic Cemetery Preservation. Crime, poor maintenance and difficult access threaten to erase the historical treasures in old public cemeteries, plantation graveyards, farmstead plots, potter’s fields and now-defunct church burial grounds.

Charlottesville, Va.-based restoration expert Shelley Sass says cemeteries that look neglected are most at risk for vandalism. That includes secluded rural cemeteries and historic public burial grounds in older, high-crime neighborhoods. “Nighttime lighting and a locked fence discourage vandals,” adds Sass, “but one of the best deterrents is avoiding an uncared-for appearance with routine maintenance.” In cash-strapped cities, it’s often up to volunteers to take the lead.

ADVERTISEMENT

Exposure to the elements wreaks its own style of tombstone desecration, slowly obscuring engravings and artwork. Sandstone, limestone and marble are particularly vulnerable to weathering and pollution, and most wooden markers — used primarily before the 1800s — are already gone.

No matter how well-intentioned, “repairing” a tombstone with caustic materials such as concrete or bleach does more harm than good. Water and a soft brush are the safest cleaning materials. Only a restoration expert should undertake further action, such as consolidation — an irreversible, last-resort coating that preserves a stone in its current state. Contact the American Institute for Conservation of Artistic & Historic Works for a referral.

Even the best preservation efforts are fruitless if you can’t get to a cemetery or don’t even know it’s there. Our 18th- and 19th-century ancestors often were interred in family or rural plots now located on private property. Laws vary from state to state, but in general, descendants may visit graves on private property during “reasonable hours” and for purposes normally associated with a cemetery visit, so long as they use routes the landowner has designated. But the owner may not be obligated to maintain the cemetery.

ADVERTISEMENT

Some states, such as Texas, address this problem by allowing citizens to seek conservatorship over cemeteries on private land. The conservator may clean up the cemetery, provide ongoing maintenance and even confer with the landowner about erecting a fence to keep livestock from knocking over stones.

As local governments and volunteers struggle with solutions to cemetery preservation, Thompson, who helped evaluate the damage at Old City Cemetery, advises genealogists to “document what’s there now by photographing tombstones, transcribing inscriptions and drawing maps of burial plots.” (Preservationists recommend against making rubbings of deteriorating headstones.) In my own case, my great-great-grandmother’s grave marker answered a years-long puzzle about her death. Reading a transcription, though, wouldn’t have matched the feeling of actually visiting her burial site — I daresay most family historians would agree.

Historic Cemetery Preservation Resources

These resources can help you plot your steps for saving historic cemeteries in your community:

Alabama Cemetery Preservation Alliance

American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works

Association for Gravestone Studies

Florida’s Historic Cemeteries: A Preservation Handbook

Internment.net: How to Record a Cemetery

Advisory Council on Historic Preservation: Historic Preservation Contacts and Resources

A version of this article appeared in the October 2006 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

ADVERTISEMENT