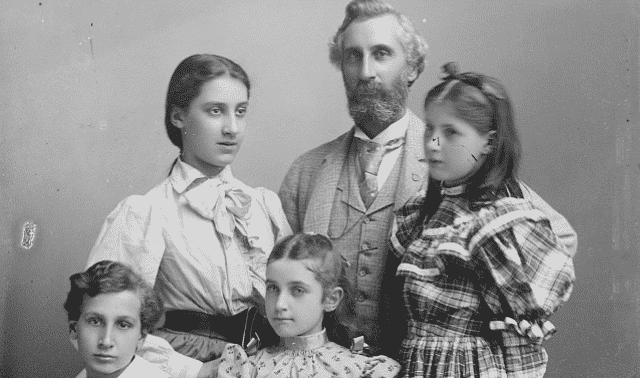

Finding it difficult to uncover your female ancestors in typical genealogy records? There’s good reason you struggle to add women to your family tree: In the past, a woman’s legal status became feme covert (literally a “covered woman”) upon marriage. She not only gave up her name, but her rights as well. As her identity became absorbed into that of her spouse’s (in official documentation, anyway), so too did any record of her individual accomplishments.

In an article for The Journal of American History, “Of Pens and Needles: Sources in Early American Women’s History,” author Laurel Thatcher Ulrich points out, “Women ‘covered’ in surviving documents were visible in ordinary life… [they] were everywhere, in gardens and fields, kitchens and taverns, on horseback and in canoes, in stagecoaches and at ferry crossing, in church pews and at the front lines of armies.”

This list could go on. But what of her accomplishments, activities and life trials? What of the sorority sister? The divorcée? The businesswoman? The social reformer? The patient?

Do records of her exist? Perhaps—if you know where to look. The typical, easily accessible records most genealogists access on a regular basis—censuses, church, vital and so on—often aren’t enough. Women are likely under the guise of their married names in these records, if they’re mentioned at all.

Therefore, we must look to other sources of information to uncover important clues about her life and times. The following list covers resources—grouped into five categories—that you may not have considered using to find women in your family tree.

1. State and County Histories

Published histories describe a wider geographic area than other resources. And, fortunately for researchers, they’ve been created for hundreds of years. English counties recorded historical and topographical information as early as the late 16th century. Contents varied, but most consisted of the genealogies of county families and lordship descendants. Colonists brought the practice with them to America. Some publications were specific to women and covered entire states.

Possible details

- Parents’ names

- Maiden name

- Place of birth, death or marriage

- Descendants

Where to search

You can find many titles on WorldCat, or read them on Google Books. Some searchable examples available on Google Books include Mothers of Maine by Helen Coffin Beedy (Thurston Print) and A History of Adams County, Ohio by Nelson Wiley Evans and Emmons B. Stivers (self-published).

Sure, you’ve probably checked city and telephone directories before. But you should also research these similar publications for evidence of your female ancestors.

2. Who’s Who

Publishing biographies of “distinguished Americans” since 1898, Marquis Who’s Who can be a great resource for genealogists. Founder Albert Marquis stated that the directory’s objective was to “chronicle the lives of individuals whose achievements and contributions to society make them subjects of widespread reference interest and inquiry.” Although the first few entries are usually individuals in the public eye, many are just everyday citizens. Marquis Who’s Who has also published a women-only directory, Who’s Who of American Women, since 1958.

Possible details

- Occupation

- Place of birth

- Education

- Career

- Awards

- Memberships

- Hobbies and special interests

Where to search

A subscription to the Marquis Who’s Who online database includes a feature called Who’s Who in American History, with 180,000 life stories from 1607 to today. (If you’d rather not subscribe, you may be able to access the database for free at your local library.) You may also be able to pick up a secondhand print copy of an old edition on Amazon or eBay.

3. Professional and Trade Directories

As Gena Philibert-Ortega states in her article “Genealogy Tip: Using Directories to Find Your Female Ancestor,” the idea that women never worked outside the home in the past is a huge misconception.

Women took jobs for many reasons, and cities all over the country distributed female-specific business directories beginning in the early 20th century. Boston published one as early as 1903, and Washington, DC listed 3,000 women in its 1931 directory. (Trade-specific directories, especially for medical and legal fields, had been around since the late 18th century.)

Possible details

- Occupation

- Place of business

Where to search

If believe your female ancestor worked for a company or owned her own business, check your local library for this valuable resource. Be sure to also check for directories of female-heavy professions such as nursing, midwifery, and teaching.

Although not pleasant to think about, these records can be a valuable resource when searching for female relatives. The details contained in these documents vary by location and time period. As ever, be on the lookout for maiden names and family member names listed. It also helps to familiarize yourself with old medical terminology. An excellent list can be found at www.genealogytrails.com/main/illnessdefinitions.html.

4. Insane Asylum Records

Some women who ended up in institutions had sound medical reasons to be there. Many, on the other hand, did not. Ladies could be sent to insane asylums by their spouses or families for anything ranging from post-partum depression to menopause to mere disobedience.

Keep in mind that hospitals sometimes changed names. One facility in Cincinnati, for example, was “Commercial Hospital and Lunatic Asylum” from 1822 to 1851, then “Longview Asylum” and finally “Longview State Hospital.”

Possible details

- Date of admission

- Age

- Name

- Marital status

- Occupation

- Birthplace

- Duration of insanity

- Cause of insanity

Where to search

Many records are held by state and local historical societies, and some have been transcribed. Blacksheep Ancestors has an index of patients for selected states available online: Colorado, Delaware, Idaho, Illinois, West Virginia, Wisconsin and Wyoming. And you can find some international records at www.olivetreegenealogy.com/Lunatics.

5. Tuberculosis Sanitarium Records

Prior to the discovery of antibiotics, tuberculosis hospitals were established in the late 19th and 20th centuries as a means to treat a variety of long-term illnesses, although tuberculosis was the most prominent. (Note: Although the meaning is essentially interchangeable, some hospitals used sanitarium while others opted for sanatorium.)

Possible details

- Name

- Age

- Birth date and place

- Date of admission

- Date of discharge or date of death

- Medical condition

Where to search

As with insane asylum records, tuberculosis sanitarium records are mostly maintained by historical societies. Begin by narrowing down the name of the hospital your relative may have been admitted to. Then, check at the state or local level for records.

Some hospitals were state-run, and patient records may not be available to the public. If this is the case, try seeking out hospital annual reports or bulletins at local libraries instead. For example, the Arkansas Tuberculosis Sanatorium published the monthly Sanatorium Outlook bulletin, which listed the names of arriving and departing patients. Also check the hospital and medical records in collections at the Digital Public Library of America.

6. Eugenics Record Office Records

Popularized in the early 20th century, the misguided field of eugenics sought to “improve” human genetics through the exclusion of specific genetic groups. The Eugenics Record Office in Cold Spring Harbor, New York, was the movement’s research headquarters. Often referred to as the ERO, researchers there were tasked with gathering biological information on the American population.

The Archives at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory website states the ERO was “devoted to the collection and analysis of American family genetic and traits history records,” including family study files. These files include individual analysis cards, pedigree charts and other related forms. The sheer amount of genealogical information gathered is astounding, some going back to the early and middle 1800s. (Below is just a partial list of the statistics collected.)

Possible details

- Full name or full maiden name

- Birth date and place

- Marriage date and place

- Total number of sons and daughters

- Diseases and illnesses

- Surgical operations

- Education

- Religious affiliation

- Age at death

- Cause of death

- Height and weight

- Eye, hair and skin color

Where to search

You can find a list of collections and which institutions hold them at https://www.cshl.edu/archives/institutional-collections/eugenics-record-office/.

7. Settlement House Records

The goal of the settlement movement of the late 18th and early 19th centuries was to connect the middle class to low-income families through shared living space. Settlement houses were established in poor neighborhoods, where volunteers from higher socioeconomic circles ran them. Families lived together under one roof, and they were provided with daycare, education and healthcare.

While the most famous example is Chicago’s Hull House, settlement houses were established throughout the United States. Contents of records vary greatly. Contact the specific library or archive holding the collection for more information.

Possible details

- List of house residents

- Resident evaluations

- Meeting minutes

- Reports prepared by staff on children and adults participating in house-sponsored clubs and classes

Where to search

The University of Illinois at Chicago holds most of the records for Hull House specifically. The collection includes scrapbooks, clippings and lists of associates and residents. Visit researchguides.uic.edu/hull-house for more.

Other settlement house records availability varies by state. Two examples include the “Minneapolis Federation of Settlements records” collection, and Boston’s “Guide to the South End House Association records, 1909–1944” collection.

Newspapers are a standard go-to for any genealogical research. Marriage and birth announcements, obituaries, and property notices are all valuable sources. But when it comes to tracking down female ancestors specifically, you may have to dig a bit deeper.

8. Women’s Pages

According to Dustin Harp, author of Desperately Seeking Women Readers: U.S. Newspapers and the Construction of a Female Readership (Lexington Books), these special sections devoted to women’s interest focused on the “Four F’s”: family, food, furnishings and fashion.

The women’s section usually ran on Saturday or Sunday and (depending on the publication) included recipes, sewing hints and ladies’ club news. It’s worth checking these sections for contributors or names mentioned. The gossip and society news sections usually featured local wives, brides and daughters of the area’s prominent men.

Possible details

- Full name or maiden name

- Location

- Hobbies or interests

Where to search

Look at Saturday and Sunday editions of papers in your ancestor’s area. Identify publications using Chronicling America’s U.S. Newspaper Directory, then keyword digitized copies of that paper on sites such as Newspapers.com and GenealogyBank.

9. Unclaimed Mail

Beginning in the early 1800s, local post offices would advertise unclaimed, unpaid “dead letters” in the newspaper. In the days prior to prepaid postage, post officials hoped the recipient would see his or her name listed in the newspaper, pay the postage due, and collect the letter.

Although initially successful, by 1845 adverting costs significantly outweighed the postage recuperated. Dead letters held by post offices greatly decreased with the introduction of including a return address on the envelope in the 1850s.

Note that these notices mentioned the specific addressee by name—man or woman. That makes unclaimed mail notices a rare example of an early female ancestor being mentioned by her own name as opposed to her husband’s.

Possible details

- Full name or maiden name

- Location

Where to search

Search in digitized newspapers for sections titled, “A List of Letters,” “Letter List,” “Letters for You,” and so on. These columns were usually printed in smaller, local newspapers.

10. Notices Repudiating Wives’ Debts

“For more than 300 years,” notes Hilary Sargent in an article for the Boston Globe, “newspapers ran advertisements from men publicly announcing their wives had left them, and that they would no longer ‘be responsible for her debts.’” As early as 1656, newspapers printed these notices, and the practice continued well into the 1980s.

Although pointless from a legal standpoint, this public airing of one’s dirty laundry can be a valuable (and sometimes entertaining) resource for genealogists.

Possible details

- Full name or full maiden name

- Husband’s name

- Year of divorce or separation

- Location

Where to search

Look for these notices in the classified ads section, sometimes under the heading “Special Notices.” They may be worded: “I will not be responsible for any bill contract by my wife” or “I will not be responsible for any debts contracted by my wife,” followed by the wife and husband’s name. Very early examples will use the phase “eloped from my bed and board.” Others simply state the man posting the notice will not be responsible for any debts contracted in his name by anyone other than himself.

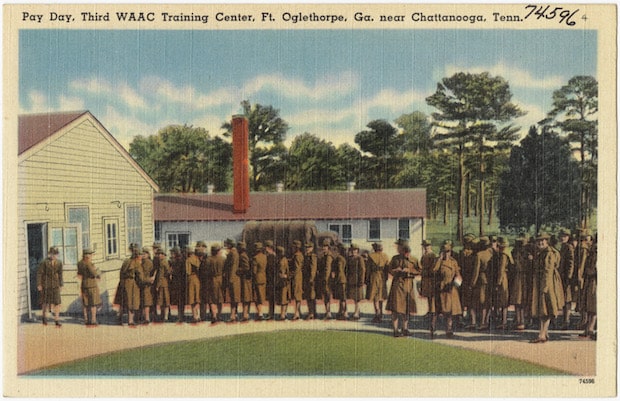

The ladies’ club movement gained popularity in the 1800s as progressive-era social reform began to sweep the nation. Women believed they had a moral duty to sway public policy and formed societies to address these concerns. Organizations and sisterhoods took up causes such as temperance, child labor and rights for African Americans. Chapters of organizations were usually established at the city or county level. As with most record collections, contents vary widely by archives. Check with the institution directly for specific information.

11. Young Women’s Christian Association

The American branch of the YWCA was founded in New York City in 1858. The YWCA offered housing, education and support with a “warm Christian atmosphere” to both single women and families alike.

Possible details

- Minutes and reports (local and national)

- Photographs

- Notes, clippings and outlines

Where to search

Beginning in 2003, the YWCA donated over one million photographs, publication pages, and rolls of microfilm to the Sophia Smith Collection of Women’s History at Smith College in Northhampton, Mass. Thanks to a grant from the Council on Library Information and Resources these records have been digitized and are available for researchers. For more information, visit libraries.smith.edu/news/2019/06/historical-ywca-records-are-now-available-through-special-collections.

12. Women’s Christian Temperance Union

With its mission to create a “sober and pure world” through abstinence, purity, and evangelical Christianity, the WCTU was influential and powerful organization in its day. Founded in 1874, it led the charge for the prohibition of both alcohol and tobacco in the United States.

Possible details

- Membership books

- Roll calls

- Minutes and reports

Where to search

WCTU records may be held at city and county levels, or with state archives. The Billy Graham Center Archives at Wheaton College holds a large collection of WCTU records. Visit for details and contact information.

13. National Association of Colored Women

When the NACW (also known as the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs) was established in 1896, it adopted the motto “Lifting as we climb,” a response to a society determined to portray African American women in an unfavorable light. Famous founders of the NACW included Harriet Tubman, Margaret Murray Washington and Mary Church Terrell, but total membership numbers soared to 300,000 by 1924. Was your ancestor one of them?

Possible details

- Meeting minutes

- Attendee names

- Various correspondence

Where to search

Bowdoin College in Maine holds the “Records of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, 1895–1992” collection which includes subject files, meeting and convention notes, and correspondence. Search for that collection title at library.bowdoin.edu. Search city- and state-level libraries and archives for records of those areas’ clubs.

14. Daughters of Rebekah

Usually referred to as “The Rebekahs,” this group was founded as a female auxiliary of the fraternal order Independent Order of Odd Fellows. Like the IOOF, it is a service-oriented organization that promotes both personal and social development. Membership in the Rebekahs (and other similar sisterhoods) reached an all-time high in the early 20th century, with over a million members reported in 1923.

Possible details

- Dates of membership

- Rank

- Offices held

Where to search

A page on the Independent Order of Odd Fellows website addresses genealogists specifically and notes records for membership are held at Jurisdiction (Canadian province or US state) level. To obtain specific record information, write to the Jurisdiction your ancestor belonged to, and include the following information: name, town of residence, years of residence and year of death.

Make no mistake: Finding your female ancestor may not take outlandish measures, but it will require some extra effort.

Related Reads

A version of this article appeared in the January/February 2020 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Last updated: March 2024