Finding female ancestors is a notorious roadblock for researchers because of the simple fact that women’s names historically changed after marriage. In fact, a married woman’s identity became so affixed to her husband’s that even her own death record or obituary might make no mention of her maiden name.

Other records may give only a first name or nickname: Polly, Fanny or Sally. Finding that hidden maiden name is crucial to identifying the woman’s parents and extending her family line, and a challenge nearly every genealogist faces at some point.

Fortunately, you can usually solve these maiden-name mysteries with a little legwork. We’ll look at 12 types of resources to explore, from easy-to-find documents to those that require more digging.

As you search, keep an eye out for other names mentioned in your ancestor’s records because the people a woman interacted with and relied on could have been related to her.

1. Family Sources

Keepsakes handed down from one generation to the next often provide information about the wives, mothers, daughters, sisters, aunts and grandmothers in a family:

- Letter and diaries: Many women saved personal correspondence or kept diaries. As you read these, make a list of both familiar and unfamiliar names, noting any relationships you perceive.

- Labels on photographs could suggest unknown family members or old hometowns.

- Scrapbooks and baby books might contain newspaper clippings, lists of people who attended events, certificates or programs, and other clues to family origins.

- Bibles: If you’re lucky enough to have inherited a Bible, check inside to see if it includes any handwritten notes about the family.

- Old recipe cards can even help you make a connection to female relatives.

If you didn’t inherit many keepsakes yourself, is there someone else who did? Now is the perfect time to talk to people who might know more about the family. Interview older relatives and see what they might be willing to share with you. Use what you learn as a starting point for a deeper search. Just remember to check and verify family lore—whether written or oral—with other records.

2. Civil Marriage Records

No doubt one of the first things you’ll look for is a legal record of your mystery female’s marriage. Such a record could take several forms. And even if your ancestor’s maiden name wasn’t mentioned, a witness or other person named might be one of her relatives (i.e., someone who shares her last name).

Religious marriage records typically pre-date those kept by the civil government. Different localities began keeping those civil marriage records at different times—often at the town or county level before the state level. Some localities lost marriage records due to courthouse fires or other disasters.

Depending on the place and time of the event, you could find:

- A marriage license, which was issued by a civil court and signifies the couple’s intent to marry. Older licenses name both parties and may also mention someone who certified they were of legal age or gave permission for a girl to marry. Could that person be the bride’s father, brother, stepfather or uncle? Modern licenses typically state the parents’ names.

- A marriage bond also shows intention to marry, and was posted for the general public to see. Through the early 1800s, bonds often assured the groom’s legal right to marry the bride. The bondsman who cosigned was usually a family member.

- A marriage return affirms that the union took place on a certain date. Returns typically name the bride, groom, officiant and sometimes a witness.

Don’t worry if no marriage records exist for the place and time you’re researching—there are plenty of other options to explore. (Read search tips here.) In cases where you don’t know when or where the couple married, try to identify a range of potential years based on their ages and the birth of their first child. Work with other clues to figure out where at least one of them lived during that time period.

3. Religious Records

Various types of church records could also document a woman’s maiden name. As with civil marriage records, you may find a parish or church register that lists when and where a wedding took place, or evidence of marriage banns that were publicly announced.

In addition, frontier ministers often kept personal journals of the marriages and baptisms they performed in their travels. Some surviving journals of this type have been transcribed and published.

Baptism records of children, in general, are excellent sources for maiden name clues. Some state the mother’s maiden name outright, while others name the child’s sponsors or godparents. These were usually family members—perhaps the mother’s parent, sibling, or aunt or uncle.

Where can you find church records? In many cases, they’re still held by the church itself, or by a successive congregation. Older records might have been turned over to religious archives. Others have been indexed, published, microfilmed or digitized. While it may take some probing, the time you spend searching for church records could really pay off.

4. Children’s Vital Records

Children’s birth records are one of the most reliable sources of mother’s names. Most were created at or near the time of birth and reported by someone with first-hand knowledge of it. While some merely give the mother’s first name, others specifically ask for her maiden name.

Like marriage records, birth and death records in the United States were usually kept first at the local level, and only later at the state level. Look for digitized records and indexes for your ancestor’s locale or state. If you’re working from an index, check to see how you can obtain a copy of the original record. Note that records created within the last 100 years or so may be restricted by privacy laws to only certain individuals.

Children’s marriage records can be a similarly rich source of information, since they too provide first-hand accounts. Some directly ask for the mother’s maiden name. Others may indicate where the bride and groom were born, offering a clue to where their parents could have married.

Seek birth and marriage records for all of a woman’s children, including those she may have had by another husband. Doing whole-family research is crucial when trying to solve a tough genealogical problem, because you never know where a golden nugget might be hiding.

5. Death Records

Until recently, relatively few death records asked for maiden name or the parents of a woman who was married or widowed. Certificates (and the indexes created from them) commonly do ask for this information. But even then, the answer is too often “unknown.” Branching out beyond the woman herself, however, can be fruitful.

When looking for a widow, search for her husband’s death record, as it will sometimes indicate her maiden name. Also look for the death records of all of her children, especially those of any who died young. Compare what these records say about the mother’s name and birthplace.

Keep in mind that death-record informants may have had only second-hand knowledge of a person’s life details. Even those who were confident about biographical information might have been too grief-stricken in the moment to be accurate, or even had reason to fib. Verify what you find with other sources.

6. Cemetery Sources

Gravestones often indicate a birth date or year, but typically lack other details to help connect a woman to the family she was born into. Burial records, however, could provide more information.

Find out who or what municipality takes care of the cemetery, and inquire about any records they might have. These could give a maiden name, a place of birth or even a father’s name. Burial records of some cemeteries have been abstracted and published, while some others can be found in online indexes.

If possible, visit the cemetery in which your ancestor is buried in order to see who is buried near her. The arrangement of graves frequently suggests relationships that aren’t apparent when viewing a single gravestone online. Because the last names are different, you might not realize a woman was buried near her parents or siblings until you see the stones together.

Take special note if she had a child who died young. More than one family mystery has been solved by finding a child buried with his or her (maternal) grandparents.

7. Censuses

Our ancestors typically found spouses within their own community, and newlyweds often took up residence close to home. Look at a couple’s first census record and note the neighbors living nearby. Compare the neighbors’ records to those of the previous census. Did any of them “lose” a daughter of marriageable age? If so, what was her name? Investigate the family to learn more about her.

Women often became caregivers of elderly parents or disabled siblings. If you find a census record showing an older man or woman living with your couple, he or she was likely a relative. This can be a good clue to a potential maiden name. Try to learn more about the person and how he or she was related.

Conversely, when a woman died young, her parents or siblings might have taken in one or more of her children, either temporarily or permanently. If you find a census record showing a child living with people you don’t recognize, examine them closely. They could provide your missing link.

8. Newspapers

Newspapers can be a rich source of clues about a woman’s identity. Among the things to look for:

Marriage announcements generally give the bride’s maiden name and often the names of her parents. Look for short notices in the 1800s, typically combined with other community news. Modern announcements may be longer and full of details.

Golden anniversary announcements are a gem for long-married couples. They can reveal the parents and birthplaces of both the husband and wife, as well as their marriage date and place.

Social notices, such as those noting visitors from out of town and trips taken to visit relatives, can help link a woman to her parents or siblings. These are common in small community newspapers.

Obituaries or death notices may name a woman’s parents or give her birthplace. Even if they don’t, look for lists of surviving relatives or of those who attended the funeral. Investigate those names to see if some could be siblings.

Obituaries of relatives are definitely worth seeking out, too. Look for obituaries of all of a woman’s children, even those who moved far away. If you’ve found potential sisters or brothers, notices of their deaths could give you more material to work with.

9. Published Sources

Old town and county histories contain information about early settlers and biographical sketches of select residents. You could find clues to a woman’s maiden name or family origins in the sketch of her husband, son, son-in-law or grandson. Since you don’t know what the original source of this information was, you’ll want to confirm it with other records.

Published family histories that trace the descendants of a shared ancestor are another potential resource, as they often list maiden names of women who married into the family. Sources, however, are often lacking. As with town and county histories, you’ll need to verify what you find.

Online family trees are both a blessing and a curse, and must be used with caution. It’s easy (and unfortunately common) for erroneous material to be copied and spread among these trees. Look for the records and sources behind the “facts.” Do these align with other materials you’ve found? Look, especially, for any evidence provided for parent-child relationships.

Be wary of connections that are not backed by actual records. Do your own research and try to find evidence to either support or refute them.

10. Court Records

In the eyes of the law, a married woman was historically “feme covert”—covered by her husband. She couldn’t conduct her own business or handle her own affairs. Nonetheless, you may find court documents that link her to her birth family in some way, such as:

Estate records naming her and her husband as heirs to property are a strong sign of kinship. This could occur during the probating of her father’s or widowed mother’s will, estate inventory and appraisal, or probate settlement. Try to get all available estate records, including the complete case file if it still exists.

Guardianship records may have been created if a woman’s husband died while their children were young. Guardianship was designed to protect the children’s property against potential claims—including those of their mother’s future husbands.

Divorce records often summarize the details of the marriage, thus revealing the woman’s maiden name.

11. Deeds

If you haven’t found a probate record naming your mystery woman, consider deed records. Sometimes when a father died, his land passed on to his heirs without a court settlement.

The heirs (usually siblings or children of deceased siblings) could each decide what to do with their share. Typically, the ones who had moved off the homestead sold their shares to the brother or sister remaining on the homestead, or all of them sold the property to a third party.

This created a series of “quitclaim” deeds, in which the heirs gave up their shares. Look for a quitclaim deed that names both the wife and her husband. Does the deed say whose property the land was? Who did the survivors sell it to? Search for other people who quitclaimed land to that person. Chances are good that they’re all related and, by researching them, you may develop a picture of the whole family.

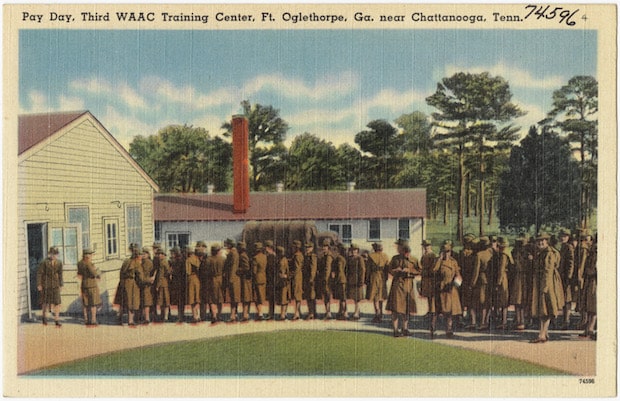

12. Military Pension Records

Was your female ancestor married to a veteran of the Revolutionary War, War of 1812 or Civil War? If so, did he receive a pension, or did she apply for one after his death?

Widows’ pensions, in particular, can be chock-full of personal information. Among other things, you could learn the widow’s maiden name, the date and place of her wedding, the birth dates of minor children, and details about the veteran’s life and death.

Revolutionary War pensions are available online at FamilySearch, Ancestry.com and Fold3.

Fold3 also holds free digitized pension records from the War of 1812, although the series is still incomplete as of writing. Ancestry.com and FamilySearch each have an index to War of 1812 pension files.

Find indexes to Civil War pensions at Ancestry.com and Fold3. Use that information to request the complete record file from the National Archives. While it might not be the simplest task, uncovering a woman’s maiden name is always an exciting discovery. Using all available resources and following clues wherever they lead will help you unlock the mystery of her origins.

Related Reads

A version of this article originally appeared in the March/April 2023 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated, January 2025.