Jump to:

1. Dispel romantic notions

2. Keep multiples in mind

3. Look at home

4. Get government assistance

5. Surf the web

6. Go to church records

7. Check cemeteries

8. Read the news

9. Call on military records

10. Take clues from the census

11. File for divorce records

12. Examine family photos

Related Reads

Wedding bells ring at each junction, more or less, of your family tree. You’d think so many weddings would have you practically tripping over marriage records, but in reality, finding proof of all those nuptials can be like searching for The One. Maybe you’re having trouble tracking down the couple’s marriage certificate, or the wedding took place before vital record keeping began. Happily, official records aren’t the only evidence a marriage occurred.

The good news is that many kinds of documents provide details on when and where a couple wed, and maybe even who officiated the blessed event, which family members attended and what they gave the bride and groom. The less-good news is that not all of these records exist for every time and place. But can they help you track down the newlyweds on your family tree? These 12 tips will assist in your search for ancestors who tied the knot.

1. Dispel Romantic Notions

You know the nursery school rhyme, “first comes love, then comes marriage, then comes [fill in the blank] with a baby carriage.” But in reality, ancestral weddings often had nothing to do with love. Our contemporary notion of romantic love didn’t rise in popularity until the late 18th century. Courtship and marriage often were about economic and social alliances, not finding a soul mate. For instance, in Colonial Connecticut, several intermarriages between the children of James Avery and Thomas Minor solidified political links between these two prominent founding families.

And the baby carriage didn’t always come later, so throw aside any assumptions about old-fashioned propriety when estimating marriage dates: Babies were frequently born before a wedding or suspiciously less than nine months later. Imagine my surprise when I discovered in town meeting records that my betrothed-at-19 great-grandmother Sarah had previously been married at 16. Further research revealed the first marriage occurred only days before she gave birth to a child who, sadly, died shortly after. You may find records “fudged” with incorrect dates to hide the truth.

Knowing your ancestor’s age will help you identify him or her in marriage records. Age at first marriage varied depending on the laws and customs of the area. Men generally waited to marry until they had sufficient property, tools and livestock to support a family, usually between ages 22 and 27. Brides were typically younger, with most marrying between 17 and 20. Frontier dwellers often wed younger, resulting in more childbearing years—a necessary factor for families in need of labor. An indentured laborer couldn’t marry until the end of his or her contract. Many immigrants entered into five- to seven-year contracts starting at age 21. In general, siblings married in birth order from oldest to youngest.

2. Keep Multiples in Mind

Multiple marriages were common in the days when a woman had few options for supporting her family and a man needed a partner to care for his children and home. When many women died in childbirth and disease and injury often meant early death, speedy remarriage was a necessity to keep a household functioning. A person who seems to have married late in life might have a prior spouse (or two). And don’t assume that all the children in a household are biologically related to both parents: You may be looking at a blended family.

3. Look at Home

Start your search for marriage documents at home. Marriage certificates and licenses, a ketubah (Jewish marriage contract), newspaper engagement announcements, wedding programs and other records might be tucked away in family papers. Check family Bibles for pages with recorded births, marriages and deaths. Sometimes, those handwritten notes are the only documentation of the nuptials. In the 19th century, a common wedding keepsake was a pre-printed form completed with photographs of the bride and groom, and often the wedding officiant, plus details of the event.

4. Get Government Assistance

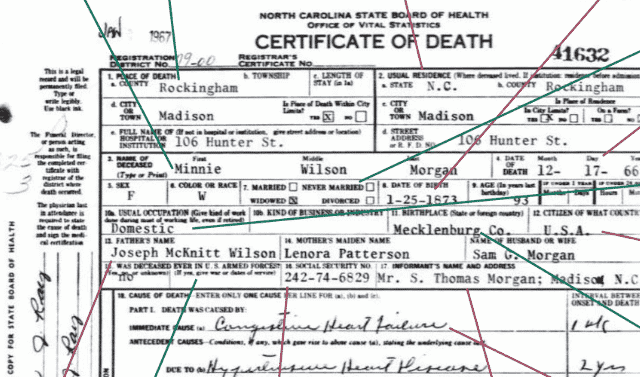

In most states, the town or county is legally charged with recording marriages and forwarding paperwork to the state vital records office or health department (Louisiana, where marriage records stay at the parish level, is one exception). The dates when this system began vary by state, and even after laws mandated vital record-keeping, compliance wasn’t perfect. In 1853, for example, Rhode Island required localities to keep marriage records, but not every city and town sent copies of records to the state. Some states, particularly in the South, didn’t start keeping records until the 20th century.

If your ancestors married before that date, don’t despair: Many towns and counties recorded marriages before states mandated it. Local governments may have records including marriage registers, licenses, returns and certificates. State archives also may have gathered collections of these local records. Records may be spotty, though: In Boston in the early 19th century, for instance, only about 50 percent of vital events were recorded.

For weddings after statewide record keeping began, you can request marriage certificates from the vital records office or department of health. Old records might’ve been transferred to the state archives. Click here for contact information. For town and county records, check with the clerk of court or city hall. You may have to pay a fee or prove a relationship to the couple named in the record. In addition, privacy laws might restrict access to records created relatively recently.

FamilySearch has microfilmed and digitized many counties’ and states’ vital records. A place search of the online catalog will tell you whether marriage records from your ancestors’ hometown were filmed.

5. Surf the Web

Industrious genealogists may have posted information about your ancestors’ wedding in online collections of record images or in indexes (which contain partial information that can help you request an original record). The Western States Marriage Record Index, for example, includes details about marriages in 12 states. The Indiana State Library has posted a database of marriages in the Hoosier state through 1850. Databases at FamilySearch.org and the subscription website Ancestry.com are bursting with names of happy couples, such as the former site’s Alabama, County Marriages, 1711-1992; and the latter’s Missouri Marriage Records, 1805-2002. To find similar indexes, run a web search on the county or state name and marriage records genealogy.

6. Go to Church Records

Churches generated several types of marriage records, including banns, sacramental registers, bulletin announcements and meeting notes. Quaker teachings called for those who married outside their faith to face disciplinary actions from their meeting. You’ll find mention of these actions and the marriages in the records for their meeting. Some church records will help you jump back generations in your family tree: French Canadian marriage documents, for example, give the bride’s parents’ names.

To locate religious records, you’ll need to determine your ancestor’s religious denomination and, ideally, the place of worship where he was married. Then you can write to the church or the local denominational archives to request the record.

Does family lore say your ancestors married by a traveling minister? This was especially common on the frontier, where churches were few and far between. The marriage may be recorded in a nearby town. In addition, itinerant ministers usually kept notebooks recording ceremonies they performed. Many of these books ended up in manuscript collections in local libraries and historical societies. The Library of Congress’s National Union Catalog of Manuscript Collections which has descriptions of manuscript collections from libraries across the country, can help you locate these documents.

7. Check Cemeteries

Frustrated by the lack of marriage data for a couple on your family tree? Double-check their gravestones. Some stones note the number of years a couple was married. A stone’s inscription also might indicate a woman was her husband’s second or third spouse, or you might find a man’s grave surrounded by his wives.

8. Read the News

Although newspapers didn’t tend to dwell on the weddings of average folk, you might find a line or two that mentions a wedding in the family. When Jule Goodney married Addie L. Jones Oct. 18, 1888, their wedding notice in the next day’s Worcester Daily Spy (Massachusetts) reported who officiated, the location of the wedding, the names of the wedding party and a list of gift-givers. Wedding articles for the mid-to-late 20th century might list everything from significant guests to details about the bride’s attire. Once you get search results at the historical newspaper subscription site GenealogyBank, you can use category filters to narrow the matches to just marriage notices.

You’ll find other types of wedding coverage, too: In the Colonial period, for example, marital discord was newsworthy. Husbands could print notices denying their wives credit and the wives often printed colorful rebuttals. Amid the juicy details, the unhappy couple might give details such as when they married. Besides GenealogyBank, you can search newspapers at the Library of Congress’ free Chronicling America, Google, and subscription sites Ancestry.com, Newspapers.com, OldNews.com and NewspaperArchive.com. The public library or state archives where your ancestor lived may have local papers on microfilm or digitized—ask your librarian about borrowing the film through interlibrary loan.

9. Call on Military Records

Veterans usually mentioned their dependent spouses and children in their pension applications. Widows of Revolutionary and Civil War veterans could petition for pensions based on their husbands’ service. They had to supply proof of the marriage, usually a witness vouching for the couple and supplying details. When the last living Revolutionary War widow, Esther Damon, applied for a pension in 1855, her mother gave testimony for the marriage of the 17-year-old Esther to her 75-year-old spouse. Applicants sometimes even tore the family record pages out of family Bibles and sent them along as evidence.

Military pension records for various wars are digitized and/or indexed on Ancestry.com, Fold3.com and on HeritageQuest Online (accessible free through many public libraries). Not all pension records have been digitized or microfilmed. You can request copies of paper records for a fee from the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). Note that Civil War pensions of Confederate soldiers would be with the state government where the veteran or his survivors lived when applying for the pension.

10. Take Clues from the Census

Not sure when your great-grandparents married? Maybe the census can help. Starting in 1880, the census mentioned marital status—married, single, widowed or divorced. The 1850 through 1880 census mentioned whether a married couple was wed within the year. In the 1900 census, you’ll even find a year of marriage. If you see the term stepson or -daughter in the column for relationship to head of household, or children older than the length of the marriage, you have evidence of a previous marriage. Census records are digitized on Ancestry.com and subscription site Archives.com. Some are on the free FamilySearch.org. NARA facilities have census records on microfilm, as do many large genealogy libraries and FamilySearch Centers.

11. File for Divorce Records

Though less common than it is now, divorce wasn’t unheard of in our ancestors’ day. Even couples who didn’t follow through with a divorce may have filed. Records of divorce can include the wedding date and place, lists of children and their ages, and depositions from family and friends. Finding divorce records can be challenging. You might locate them in legislative proceedings (early in US history, state legislatures would hear cases), court records or even mentioned in local newspapers.

Benjamin and Sarah Ballou of Rhode Island married in August 1770 and divorced a quarter of a century later. In her petition for divorce, Sarah stated that Benjamin left her with nine children and ran off for “parts unknown” in 1790. He left her destitute, having sold all his property before his departure. The couple’s court documentation states that Benjamin left Rhode Island for New York, where he married another woman and started a new family.

12. Examine Family Photos

You may have an ancestral wedding photo and not realize it. For most of the 19th century, brides rarely wore white. That color was worn primarily by wealthy individuals and royalty, such as Queen Victoria, who could afford a dress that was worn just once. Most women wore their best dresses on their wedding day.

Wedding portraits not only bear witness to nuptials, but also contain clues to when the event occurred, where the ceremony was performed and who took part in the wedding. The photo’s format (daguerreotype, tintype, black-and-white paper print or color print) and the clothing portrayed can help you determine a wedding date. For help dating wedding dresses, consult Wedded Perfection: Two Centuries of Wedding Gowns by Cynthia Amnéus (D. Giles Ltd.). Keep in mind, though, that a bride might be wearing her mother’s or grandmother’s gown.

Also look for an imprint displaying the photographer’s name and town, then use city directories to determine when the photographer was in business.

Tip: Be prepared for inconsistencies in the organization of marriage records. Some local and state marriage records are indexed just by the groom’s name; in other instances, you’ll find cross-indexes by both bride’s and groom’s names.

Tip: Read up on your ancestors’ courtship and wedding customs. In New England, for example, the courting stick—a hollow tube several feet long—gave prospective couples an opportunity to speak “privately” while remaining supervised and physically separated.

Related Reads

A version of this article appeared in the March/April 2012 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: April 2025