Jump to:

Case 1: Mistaken Stories About Ethnic Origins

Case 2: Confusion About Settlement Patterns and Names

Case 3: False Associations with Famous People

Other Common Family Stories

Almost every family has them: cherished stories of ethnic origins, relationships to someone famous, or connections to important historical events. The list can go on and on.

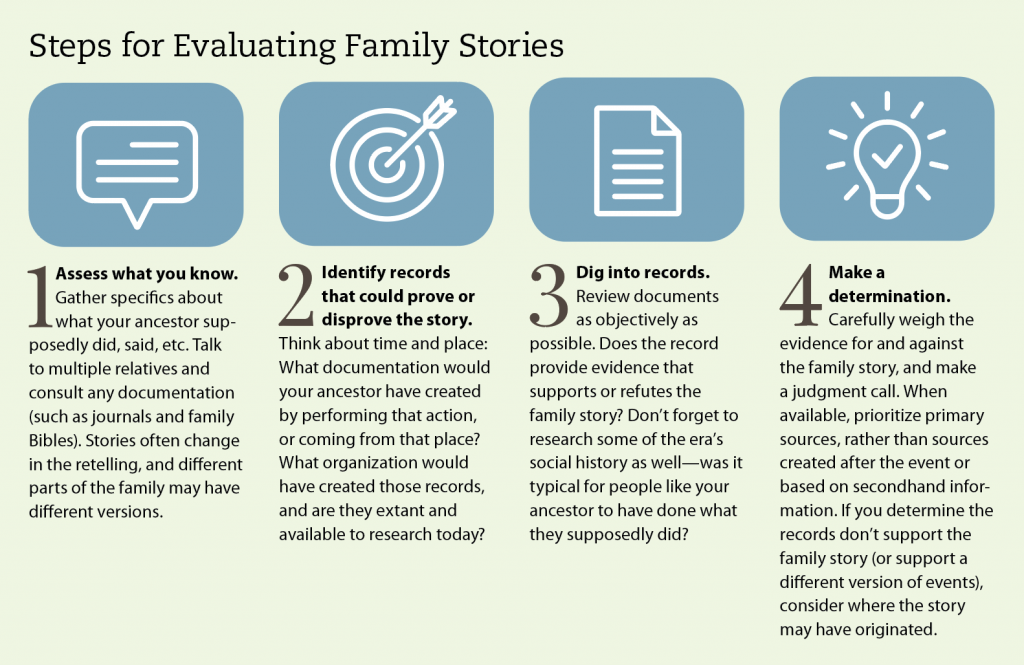

While they may be attractive—indeed, they may have been what lured you into family history in the first place—family stories are just that: stories. Oral histories, passed down from older relatives to the younger generations, can sometimes be reliable. But the passage of time may diminish the storyteller’s memories. Family stories, like information from any other source, need verification.

In fact, stories from older generations need more supporting documentation the farther back in time they reach. You might think old stories, told closer in time to when they purportedly took place, are more likely to be true. But the reality is that people who lived 100 years ago were no more likely to know about what happened a century before them than we are about what happened a century before us.

You could write a whole book on evaluating the accuracy of family stories. (In fact, I did! It’s called Sustainable Genealogy: Separating Fact from Fiction in Family Legends, published by the Genealogical Publishing Company.) Here are some key principles for determining whether or not family stories are true, explained through three case studies from my own research.

Case 1: Mistaken Stories About Ethnic Origins

My own first foray into genealogy involved learning that a family tradition of ethnic origin was false. I grew up in northern Cumberland County, North Carolina, an area settled by Europeans in the 1730s. The earliest European settlers were Highland Scots, and that ethnic group’s descendants remain widespread in the county to this day.

My mother’s family (maiden name Williams) was from that area. Her family had long been affiliated with the local Presbyterian church, and the parent church (which no longer functioned by my lifetime) was Old Bluff Presbyterian Church. The congregation was established in 1758, with the still-standing church building dating to 1858.

My family was proud of their deep connection to this church, and I was always given the impression that my Williams ancestors had been among the Highland Scots who had first settled the area. Or, if they weren’t among the original members of the congregation, they had established themselves there soon after. My grandfather and his siblings certainly thought this was the case.

What most in my family did not know was that patronyms such as Williams are associated primarily, not with Scotland, but with Wales and (to a lesser degree) England. This was a clue that the family line’s origins may have been different than expected.

I next turned to records, which cast further doubt on the family story. Primary sources collected by my mother’s cousin show my direct Williams ancestors did not arrive in Cumberland County until the 1850s (well after the community was established). Prior to that, they had lived in the neighboring county of Sampson, which was not as heavily settled by Scots.

In addition, my mother’s cousin’s research included a family history account prepared by my great-great-great-grandfather, John Carouth Williams. One statement in his writeup: “My great-grandfather, John Williams, came from Wales, a fullblood Welshman.” John Carouth (born in 1808) would not have personally known this great-grandfather, who died in 1783. Given that, I should consider this “written oral history” (more on this below).

That’s no confirmation—the research didn’t include direct support of an immigrant from Wales. But that account, coupled with my knowledge of Welsh surnames, starts to form the basis for a Welsh connection.

So where did my family’s tradition of Scottish origins come from? Possibly from another ancestral line. You’ll find that family stories—even if they aren’t correct as told—may contain a kernel of truth.

The first clue lies in another statement of the writeup by John Carouth Williams: “My grandfather on my mother’s side [emphasis added] was Robert Carruth from the lowlands of Scotland.” Sure enough, the Carruth surname is associated mainly with the Renfrewshire region in the Scottish Lowlands.

I needed to research previous generations to see if that Scottish connection was true. My cousin found the baptism record for John’s mother, Margaret Carouth/Carruth. Created at the Old Bluff Presbyterian Church in 1787, it indeed identified her parents as Robert Carruth and Margaret McFarlin. Robert Carruth had first been recorded in the region 14 years earlier, when he received a land grant in nearby Duplin County, North Carolina. His association with the first waves of Scottish immigrants is thus possible. And John Carouth Williams’ information may have come firsthand. He could well have personally known Robert Carruth—Robert died in 1820, when John was 12 years old.

This is a classic case of a long-believed ethnicity being assigned to the wrong ancestor, a frequent occurrence in family stories. Even without the written statement of John Carouth Williams, there were reasons to question the Williams family’s Scottish identity. The surname is not associated with Scotland, and the family had not lived in a heavily Scottish area prior to the 1850s. Both are factors to consider when identifying the ethnic origins of a specific lineage in the United States.

‘Oral History’ Sources

We often refer to family stories as “oral history.” But written documents might well be considered a kind of “oral history” in that they were based, not on verifiable records, but on anecdotes or communal memories.

Family stories may have appeared in print, such as in county and town histories published through the United States from the 1870s to 1910s. These often contained brief accounts of families living in the area at the time, sometimes alongside names, vital record dates, and current or previous places of residence. These facts are easy enough to verify using records, but should be categorized as family lore until then.

Other family stories or memories might appear in more-conventional genealogy records, though you’ll still want to view them with a critical eye.

For example, death certificates are primary resources for information about that event: date, place and cause. They also contain other life details about the deceased: date and place of birth, age, and names of parents. But those latter details come, not from direct observation of the event, but from an informant (usually the deceased’s spouse, sibling or child). This information is only as reliable as the person who provided it, who likely wasn’t present for those events. So you’ll want to fact-check those details (particularly for hard-to-know information like a grandmother’s maiden name) before accepting them as true.

Case 2: Confusion About Settlement Patterns and Names

Colonial American origin stories are also ripe with misinformation. One simple misunderstanding are the “Pennsylvania Dutch,” an 18th-century group many mistakenly believe to descend from the Netherlands. In fact, the group came from Germany; the term derives from Pennsylvania Deitsch, referring to settlers who spoke German.

My own direct male-line ancestors (surname Hite, originally Heyd or Heydt) were Germans who settled in Pennsylvania in the 1750s. But my father and his siblings all grew up with the understanding that our Hite ancestors had been Dutch, probably for that very reason. An added factor cannot be discounted, though; my paternal grandfather was a veteran of World War I, and may not have wanted to admit being of German descent.

Studying social history can help in such cases. As with the Williams in North Carolina, I looked for clues in geography and settlement patterns. The fact that my ancestors lived in Pennsylvania, rather than New York, was strong evidence of German descent in and of itself. The Dutch helped found New York, but were virtually nonexistant in Pennsylvania (where Germans proliferated).

But unlike with the Williams case study, surname spelling and naming patterns weren’t of much help. The spelling of Hite is ethnically ambiguous, and I suspected it had been altered in the New World (further muddying its origins). According to previous studies, some Hites did seem to descend from German Heyds or Heydts. But others came from the British Height, Hight or Hoyt. (Like Germans, Brits had come in droves to Pennsylvania during the Colonial era.) I got lucky—I found a document signed in 1787 by my immigrant ancestor John Hite (originally Johannes Heyd or Heytt). His signature was in unmistakable 18th-century German handwriting.

Those who are not so lucky and have ethnically ambiguous surnames can look for certain clues. One is the given names used by the family in the Colonial era, particularly masculine names (which were more likely to be included in records). Some extremely common given names like John and Jacob are meaningless; John can simply be an Anglicization of Johannes (as was the case with my ancestor), and the name Jacob is common among both Germans and Englishmen. But if the family has given names such as Conrad, Gottfried, and Mathias, you have a much stronger case for German origin. Likewise, names such as Joshua, Nehemiah and Ephraim are almost certainly English (or, at least, British Empire).

Surnames of neighbors also provide important clues, as people tended to settle in groups of their countrymen. A Smith family surrounded by people with surnames such as Leinbach, Baumann, or Mock may likely be German, and have Anglicized their last name from Schmidt. But if the family’s nearest neighbors are Collinses, Ellsworths, or Potters, they probably have British origins.

For given names found among multiple nationalities (such as Christopher), look to any nicknames. Germans named Christopher are often found listed in records by the nickname Stophel. But Englishmen with that name may be referred to as Kit.

Case 3: False Associations with Famous People

Ethnicity origin stories are not the only traditions that research may find flaws in. Others are relationships to a famous person with the same surname.

One notable example is Kentucky pioneer Daniel Boone (1734–1820), who has inspired family myths for seemingly every European-American Boone family. Boone is not a common surname, nor has it historically been associated with the economic elite. But its presence in your family tree does not guarantee a relationship with the famous frontiersmen.

If you have such a story in your family, first evaluate the historical figure’s proven family history. The oldest of Daniel’s male-line ancestors who came to the United States was his paternal grandfather, George Boone (1666–1744). George and his wife Mary had a large family, as did Daniel himself—opening the possibility that their descendants include someone with the Boone surname today.

But the reality is that other Boones came to the American colonies who were not members of that Boone family. Others may have come after George and Mary—maybe even centuries after. If you were to research only the descendants of George and Mary Boone, you might well miss out on your own (unrelated or distantly related) Boone family members. Worse, you might research the wrong Boone line, adding incorrect people to your family tree.

Modern technology can help. Researchers have created a Boone Y-chromosome DNA project through Family Tree DNA. Male Boones can take a Y-DNA test to determine if they match known male-line descendants of George and Mary Boone. (Female Boones can have an eligible close male relative test.) Only then could a relationship to the Daniel Boone be considered. Mitochondrial DNA tests, also offered by Family Tree DNA, can similarly provide information about direct-line female ancestors.

Note that autosomal DNA tests, such as those offered by 23andMe and AncestryDNA, do not provide enough information on earlier generations to be useful for proving or disproving relationships this far into the past. In addition, they can’t determine which ancestral couple you and a match share; they only tell you how much DNA you have in common. For example, I have autosomal DNA matches who have Hite ancestors not related to mine—I’m related to them through other lines.

Other Common Family Stories

Here are some other pieces of information or legends commonly told by US families, along with some suggestions for how to determine their accuracy.

Maiden Names

Typically hard to find, your female ancestors’ maiden names may have been passed down orally or on death certificates. While helpful, these names are not foolproof. For example, a woman may have incorrectly been assigned her sister’s married name. Check death certificates for several of a woman’s children to see if there’s a consensus about her maiden name, and prioritize original marriage records.

Birthplaces

Family stories may have mistranscribed birthplaces, or given only a general place name. County histories, death certificates and census records can all provide birthplace information, though they generally rely on secondary information and as such might not be accurate. Compare sources to each other to look for commonalities, and try to learn where the person’s parents were living at the time.

For best results, use sources in conjunction with each other (even if they don’t all agree). For example, an obituary in Iowa gave my distant uncle’s birthplace as Bucks County, Pennsylvania. But contemporary censuses and tax records show his parents living in Bedford County, Pennsylvania, some 200 miles away. An Ohio county history introduces a second erroneous location for the family—Lancaster County, Pennsylvania—albeit a few generations later.

Military Service

Details about military service can be exaggerated or outright false. Dive into extant military records, such as rosters and pension applications, to put these stories to the test. Your ancestor may simply not have been where he would have needed to be to allegedly participate in a battle. For example, the Robert Carruth mentioned earlier was said to have fought in the 1759 Battle of Quebec. But his name doesn’t appear on the roster of British units engaged in that campaign.

Surname Origins: “Two [or More] Brothers Immigrated…”

One common myth suggests that all (or many) people who have a common surname are related—descendants of different brothers who all immigrated at the same time. Families did, of course, often immigrate together. But that was not always the case, and not all immigrant men who had the same surname (even those who immigrated at the same time) were part of the same family.

Carefully document any suspected relationships, and look for clues (such as settlement patterns) that might suggest whether two people were actually related. It’s unlikely that one brother landed in Massachusetts, while the other landed in Virginia. But they may have both settled in the same community, at least initially. In cases like these, consider studying Y-DNA test results.

“My Family’s Name was Changed at Ellis Island”

No, it wasn’t. Agents at Ellis Island had pre-made passenger lists in front of them, and merely checked off people as they arrived. They did not listen to the immigrant speak his name and write their best spelling guess, nor did they intentionally change the name to make it sound more “American.” (The scene in The Godfather, Part II where Vito Andolini’s name is changed to Vito Corleone at the station has no basis in historical fact.)

Some families chose to change their names around the time of immigration of their own volition, or felt forced to do so by societal pressure. But this was not done at Ellis Island.

To summarize, any family tradition must be verified with primary sources, rather than serve as the basis for serious genealogical research. If you unconditionally accept every story passed down by family members, you’ll find yourself walking down false paths—ones often hard to turn back on.

A version of this article appeared in the May/June 2022 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Related Reads

FamilyTreeMagazine.com is a participant in affiliate programs through Amazon and Genealogical Publishing Co. It provides a means for this site to earn advertising fees, by advertising and linking to affiliated websites.