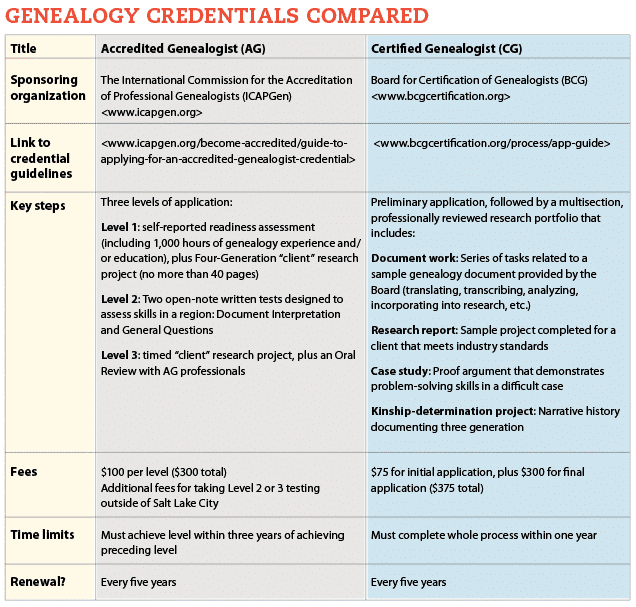

If you’ve ever seen an AG or CG after a genealogy lecturer’s name, you may wonder what those acronyms mean. A genealogist who holds one of these professional credentials has completed a rigorous process designed by a genealogist organization. At the end of the process, they’re awarded either the Accredited Genealogist (AG) or the Certified Genealogist (CG) credential. The two largest US bodies who offer credentials are the International Commission for the Accreditation of Professional Genealogists (ICAPGen) and the Board for Certification of Genealogists (BCG). In addition, a newer organization, the Council for the Advancement of Forensic Genealogy (CAFG), is now offering the ForensicGenealogistCredentialed (FGC) credential.

Read on to learn how to achieve the AG and CG credentials—and what kinds of skills a professional researcher needs in the first place.

Why Should You Get Genealogy Credentials?

In short: Credentials help you become a better researcher, even if you don’t plan on helping paid clients. The process will push you to gain new skills, making you more efficient as you work on difficult cases in your own research.

And if you are interested in getting paid to do genealogy, earning a credential will give you confidence in handling a variety of research issues. Clients will trust you more with their research because of your proven abilities. In fact, if you’re interested in doing heir research, your credential will stand in most courts, and you’ll be recognized as a qualified expert witness in estate and kinship matters.

Credentials also serve as an additional marketing tool, adding you to rosters on organizations’ websites, and setting you apart from other candidates for writing and lecturing opportunities. And each professional organization has a code of ethics that provides you with guidance when approaching your work. When signed, the code assures a client of your integrity.

How to Earn Accredited Genealogist (AG)

The AG credential is awarded by ICAPGen, a nonprofit organization. Its website provides information about the organization, maintains a directory of AG professionals, and details the process of becoming accredited.

To begin, you first must choose from more than 25 testing regions in the United States and other countries such as England, Germany or Mexico. (As the “International” in its name implies, ICAPGen has a global focus.) Specializing in a country or region allows you to become an expert in a particular area, learning specific research skills and methodology.

ICAPGen has developed a testing program that entails three levels. You must pass each with a 90% rating, but you can retake any portion if you don’t meet that benchmark. Each level has a fee, and you have three years after passing a level to pass the next one. The credential must be renewed every five years to ensure you’re keeping up with new developments in the industry.

Let’s look at each level of ICAPGen’s accreditation in detail. For up to date process notes and guidelines, visit ICAPGen’s guide.

Level 1

Level 1 begins with a readiness assessment. You’re required to have accumulated 1,000 hours of overall genealogical research experience, with at least 500 of those hours in your chosen region. Additionally, you’ll need 80 hours in each administrative division in your region, such as a state or province. You won’t need to submit a detailed report; this evaluation is based on the honor system.

In addition to actual research, any effort to gain experience can be counted toward your total—watching webinars, attending genealogy conferences, reading books and more. You may want to use some of that time to create reference guides for each of the administrative divisions in your region. (These will come in handy during your Level 2 test. More on that later.)

When you feel you’ve amassed your required experience hours, you’ll move on to the Four-Generation Project. In this exercise, you choose a family to research as if it were a client project and document four of its connecting generations, beginning with a person of interest. That starting individual must be deceased and have been born more than 80 years before the date of your submission. The focus individual for each generation must have experienced at least one life event in your region of specialization.

As your research comes together, you’ll produce a report between 25 and 40 pages long that states your objective, summarizes your findings, and provides future research recommendations. The report should be formatted as if being presented to a client, and demonstrate appropriate strategies for the region.

Along with the report, you’ll also submit:

- a pedigree chart showing the four generations

- at least three family group sheets

- copies of source documents

- a research log, including both positive and negative search results

Level 2

Level 2 involves two timed tests that evaluate proficiency in your region (Document Interpretation and General Questions), each two hours long. That may sound intimidating, but don’t worry—if you’re well prepared, you will be successful. And because a professional doing client work must rely on a variety of reference material, the Level 2 tests are open-note and allow you to use the internet. Still, ICAPGen recommends you prepare a research reference guide for each of the states or provinces in your chosen area. This prep work could count toward your research hours from Level 1.

As a professional genealogist, your clients will often give you documents they’ve accumulated, and you’ll need to know how to work with them to move the research forward. So the first Level 2 test, Document Interpretation, presents you with a variety of documents from your region and asks questions about what the document is, where you might find it, and what it can tell you. If you’re testing for a region that has a language requirement, you’ll be asked to translate a section of the document. You’ll also need to create a research plan and family group sheet based on the document.

The second test, on General Questions, will test your proficiency in researching your chosen region. How well do you know the history and geography of your region? What are the key repositories in the area? To pass, you’ll need to understand this information as well as the important record types and research methodologies. Although you can use your notes, you’ll be more successful in a timed situation by knowing these details top-of-mind.

Level 3

Level 3 consists of a written exam (the Final Project) and an Oral Review. Unlike the Four-Generation Project (which could be peer reviewed), the Final Project is completed in a timed environment without any input from other researchers. This is to mirror a real-world research project; a client would expect a professional genealogist to produce high-quality research in a limited amount of time.

In the Final Project, you’ll receive a document or pedigree problem that you will use to formulate a research project: create a research plan, conduct and log the research, and write the report. You’ll have four hours for the project, and you’re asked to turn in the same elements as the Four-Generation Project: a research report, a pedigree chart, family group sheets, source documents, and a research log.

Does this sound overwhelming? Preparation and practice are key. And remember: The test can be retaken if you don’t pass with the requisite 90%.

Once you’ve passed the Final Project, you’ll schedule the Oral Review via a video-chat service. This last evaluation pairs you with AG professionals (including at least one AG accredited in your region), who will ask questions that assess your overall readiness. Their job is to ensure that you have the knowledge and skills of an Accredited Genealogist researcher in your specialty region. As part of the discussion, you may be asked questions about your region and/or Four-Generation Project, as well as questions that you missed on written portions of the exam.

Once you pass the Oral Review and sign the code of ethics, you’ll be awarded the AG credential and can attach the AG post-nominals to your name.

How to Earn Certified Genealogist (CG)

Like ICAPGen, the Board of Certification of Genealogists (BCG) is a not-for-profit organization that maintains a set of professional standards and offers a credential: Certified Genealogist (CG). And, like ICAPGen, BCG requires its credentialed members to renew every five years.

However, BCG’s credential process is significantly different from ICAPGen’s. Unlike ICAPGen, BCG has just one “level” in its process: portfolio evaluation. And, in addition to CG, BCG offers another, optional level of credential: Certified Genealogy Lecturer (CGL). The process that follows describes the core-research category (CG); see BCG’s website for more on how to obtain CGL.

Applicants submit a preliminary application (and a fee), then have one year to submit a final application, a portfolio and pay a final application fee.

Portfolios are reviewed by at least three judges, who evaluate them independently against a rubric created from BCG’s guidelines and the organization’s book, Genealogy Standards. Judges record scores and comments (which you’ll receive afterward), and portfolios are sent to additional judges if recommendations are not unanimous. If your portfolio submission does not pass, you will need to apply again, and start over with another set of work samples.

The BCG’s standards continue to evolve to reflect modern research techniques. The second edition of Genealogy Standards, published in 2019, introduced seven new standards about the use of DNA evidence. While not every problem requires using genetic testing, new and renewal portfolios will need to meet these standards if their work uses DNA evidence. In addition, samples that include DNA test results of living people should also include the testing subjects’ permission to share results.

Work products for the portfolio include:

- a signed code of ethics

- a list of development activities (which inventories educational opportunities that helped you prepare for certification)

- document work

- a research report

- a case study

- a kinship-determination project

Your completed portfolio may not exceed 150 pages. Details about the requirements are outlined in BCG’s free publication, the BCG Application Guide.

Let’s examine four of the major elements of the BCG certification portfolio.

Document Work

Skilled genealogists know how to competently read, transcribe and analyze documents, so BCG provides a document for applicants to unpack. You will transcribe the document, then identify a research question from the details and people mentioned in it. You’ll also submit an analysis of the data and a research plan outlining the first actions you would take to answer the research question you identified.

Research Report

The research report shows your ability to perform commissioned research, demonstrating how you are able to use a variety of sources to solve someone else’s genealogical problem. This work sample may not be about your own or your spouse’s family, and should be performed on behalf of another person. (In fact, BCG requires you submit the report exactly as it appeared when sent to a client.) Other requirements mimic time constraints of a real-life client project: The report is not required to be fully up to Genealogical Proof Standard (GPS), but should meet industry standards for documentation, research and writing.

Case Study

Showcasing problem-solving skills is an important part of a successful portfolio, and the case study provides an opportunity to do so. In the case study, you prepare a proof argument that resolves a considerable problem of relationship or identity that cannot be solved with direct-evidence items in agreement. This means you will choose a case you solved with indirect evidence (i.e., with records or information that builds a case for a solution, but doesn’t provide a direct answer to a research question) or after resolving conflicting evidence. Unlike the research report, the case study can be about your own family, and it should meet the GPS, as well as standards for documentation, writing and evidence-reasoning.

Kinship-Determination Project

Do you enjoy writing narrative-style family histories? The kinship-determination project shows your capability to accurately link three generations together within their historical context. The project should include two proof summaries or proof arguments, or one of each. This project can be about your own family (though not you or your own siblings), and you should ask for permission from any living subjects. Your writing should conform to standards for reasoning from evidence, genealogical proofs and assembled research.

There are many paths to success in becoming a credentialed genealogist. Give yourself time to prepare, and don’t give up! You will become a better genealogist through the process, and eventually be able put those initials after your name.

Tips for Preparing for Certification

To be successful in your goal to earn a credential, begin practicing essential researching and writing skills now. Here are some suggestions:

- Identify your strengths and weaknesses, then set educational goals using genealogy books, conferences, study groups and institutes.

- Earn a genealogical research certificate through an online course at Boston University’s Genealogy Studies Program.

- Attend conferences with lectures by credentialed genealogists.

- Visit the ICAPGen and BCG booths at national conferences to view successful Four-Generation reports and portfolios, respectively.

- Do a research project for a friend, and practice writing a client report.

- View ICAPGen videos about the Accreditation Process and Skill Building on the ICAPGen YouTube channel.

- Compare your written work to Genealogy Standards and the BCG rubrics to see how it holds up to scrutiny.

- Participate in a study group that includes peer review, like ProGen.

- Join the ICAPGen Level 1 study group.

- Participate in a Certification Discussion Group, facilitated by Jill Morelli, CG, CGL.

A version of this article appeared in the July/August 2020 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

The ICAPGenSM service mark and the Accredited Genealogist® and AG® registered marks are the sole property of the International Commission for the Accreditation of Professional Genealogists. All rights reserved.

The words Certified Genealogist and its acronym, CG, are registered certification marks, and the designations Certified Genealogical Lecturer and its acronym, CGL, are service marks of the Board for Certification of Genealogists®.

FamilyTreeMagazine.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for site to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to affiliated websites.