Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

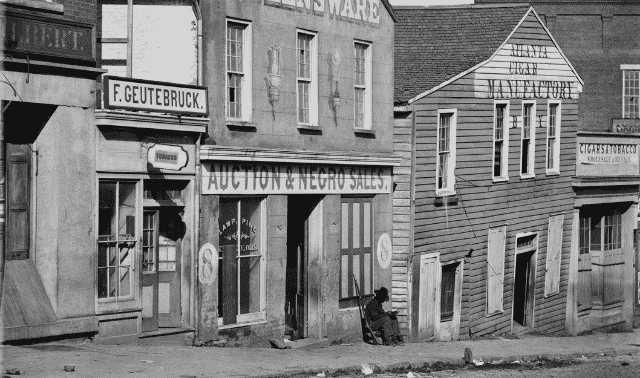

Finding the records of the enslaved within our documents can be so emotional, but we can do something to help others and come together to unite families. Below are some tips for presenting this information with care.

Making the Discovery

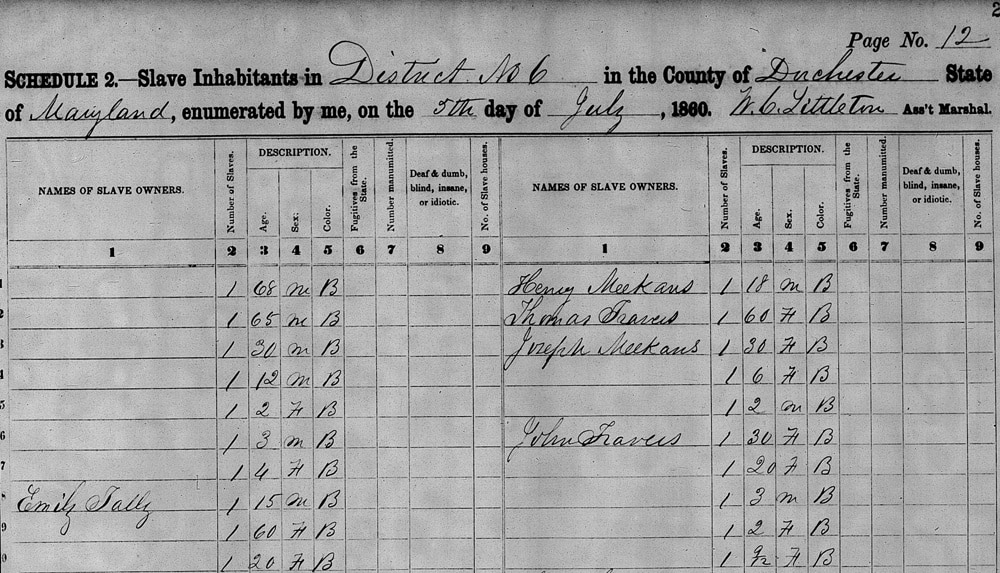

Learning our ancestors were enslavers can come from many documents—Census records, wills, probate packages, land records, newspapers, letters, diaries and manuscripts. Just about any record created during the time slavery existed until years after emancipation and decades later could contain information about the enslaved.

It’s Not Just a Southern Thing

Slavery existed from the beginning of our country’s history and continued until after the Civil War. Many people believe if they didn’t have ancestors who lived in the South, then they were exempt from finding records of the enslaved within their family’s documents. Each state had its own laws on slavery and when it was banned. Even if your ancestor lived in such places as California, Utah or Wisconsin, enslavers would often move from places that allowed slavery and brought their enslaved people with them. You may be surprised at what you find no matter where or when your ancestors lived during slavery. The records tell the truth from North to South, East to West.

Processing the Emotions

Shock is the first reaction when discovering your ancestor was an enslaver, followed by anger that your people would be involved in any way, even if you have Southern lines. Sadness, regret, embarrassment and, for some, denial comes with the discovery. Then there’s fear. What would people think of me if they discovered my family owned people? Will I be judged? Will there be community backlash?

These are all legitimate emotions. As genealogists, we can not hide facts and rewrite history. We will all find hard things that we will need to deal with. For some, it is easy to process and quickly realize they want to share their findings. For others, it takes time, and that is OK. You may want to share it, but do it in a way that doesn’t include your contact information. Your comfort level may change over time.

As you work through the emotions, please remember: we are not responsible for our ancestors’ actions.

How to Release the Names of Enslavers

While we cannot fix the past, we can step up and do something positive with the information we discover about enslaved people. We can release their names—names that haven’t been known or spoken for centuries.

What do I mean by releasing their names? We can pull out the information from our records for others to find and hopefully help make family connections. We can also transcribe any of the following items in the documents we discover:

- Names

- Physical descriptions

- Family units

- The chain of ownership

- Any clues to other records

Make sure to note the name of the enslaver and where they lived. For successful African American research, most must find the enslaver and look through their records to find clues to connect generations. Our ancestor’s records may be the bridge between those generations.

Share the information in a blog post, society newsletters, African American Facebook groups and the genealogy Facebook group of the location where the document was created; original records or copies of originals can be sent to archives, libraries and museums. Look for community efforts to collect information on the enslaved from a location.

The International African American Center for Family History Facebook page (IAAM CH) welcomes information on the enslaved.

The website Beyond Kin is a place where descendants of both the enslaved and enslaver can work together to connect families. They also have a Facebook page where conversation is welcomed and encouraged.

Community projects like Dr. Shelley Murphy’s “Finding the Enslaved Laborers at UVA” is looking for those who discover their family provided their enslaved people to build the school.

If there is no project in your community to gather the records of the enslaved, you can start one! Use the resources of the local genealogical and historical societies and ask their members to help you.

DNA is another record that may connect us to the enslaved and learn our ancestor was an enslaver. Many are surprised to learn that they have a percentage of African American DNA when their results arrive after taking a test. When contacted by someone with a higher percentage of African American ancestry, be willing to share what you know about the enslavers in your tree. If you see a match that may have resulted from an enslaved situation, be willing to reach out and share your research. Let them know you are not expecting anything from them; it is just a mutual sharing of information to learn more about your family.

I have a small amount of African American DNA through my mother’s line. I am working to learn which of her lines holds my African American ancestor. I want to speak their name, honor their life and connect them with descendants who may also be in my family’s papers. It’s a work in process, and I may never get the answers I seek. Maybe as I give back by helping others, genealogy serendipity will strike and I will be successful.

Be willing to work together to help connect the descendants of the enslaved with their families. Try researching the names to see if you can get them off the page, down to the 1870 census and beyond to a living relative.

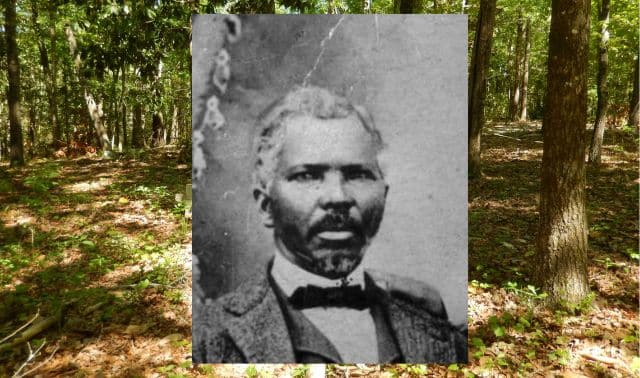

My Experience with Discovering Enslaver Ancestors

On a visit to a plantation my paternal family owned, I was thrilled to walk the land my ancestors walked. Many original buildings still stood; those oak trees had witnessed so much of their lives. Then, at the back of the property, a cemetery with no markers. Only indentations in the ground indicated someone was buried there. It was the “Slave Cemetery.” It was hallowed ground, and it changed something in me. I began wanting to do something to honor and remember the enslaved people in my family’s documents—those listed as chattel with a price on both sides of my tree.

On that visit, my tour guides showed a list of some of the enslaved who had been on the property for a couple of generations. There were names, dates of births, deaths and some dates of sales. There were women listed with their children and then those children as mothers with their children—two generations of enslaved family units. I received permission to copy the record and send it to a repository for safekeeping so that others looking for information on the enslaved on this property can find it.

I began transcribing what I was finding and creating blog posts. I donated records to archives and libraries, encouraging others to do the same.

Descendants of the enslaved began reaching out to me to share information.

January Gibson holds a special place in my heart. The enslaved son of one of my ancestors, I began looking for records in my Gibson line to connect January and, hopefully, his descendants. I found January’s mother, sisters and grandmother listed in the probate of my ancestor’s father-in-law. My ancestor bought January’s mother, Matilda, from that estate. He fathered at least two children and maybe more with her. I added him to my online trees as an enslaved son and made sure to make a note that he was the result of an enslaver/enslaved relationship and asked those who may know more and want to work together to contact me. I have been approached by several of January’s descendants. We are working together to see if we can find out more about him and his family during the time my ancestors and his family enslaved them. There is a sense of cooperation to connect family.

Working together to help each other discover information about our family can be rewarding and healing.

Remember to do something positive with the negative when finding out that your ancestors were enslavers. You can overcome the emotions associated with unexpected discoveries in your genealogy journey.

Extract the names and details of the enslaved. Share your findings publicly so they can be found when someone searches for the information. You might also consider working with the descendants of the enslaved in your documents to connect families.

By doing these things, the names of enslaved people can come out of the records, said out loud again, be remembered and connected to their descendants.

We need each other in this work to tell our family stories. Descendants of the enslaved and enslaver find documents to help each other as they research. Our history is meshed together. To tell the story truthfully, we need to acknowledge one another.

Together, we can do something positive with the negative. Working together, we can connect families.

Important Links

Finding the Enslaved Laborers at UVA Facebook Page